Royal Magazine, August 1905

Jackson, of Spence’s house, Wrykyn, was a great and many-sided man. He was at the head of the Wrykyn averages in a season when the team contained six members who subsequently, when years had rolled by, played for their Varsities at Lord’s. He was the only Wrykinian who ever got three centuries in first-eleven matches and five extra lessons in the same term. He was the only Wrykinian who ever got a double century in a house match and four hundred lines in the same week.

The fact was that Jackson on the cricket-field was a different person from Jackson off it. On the field he was a genius. Off it he was not.

The consequence was that life for him was apt to be a little feverish, and he made it more so by a confirmed recklessness and love of adventure, which qualities, though they may have made us Englishmen what we are, are somewhat unpopular among the authorities at a public school.

It was the hour of the evening meal; and Jackson, returning to his house after a long afternoon at the nets, found on his plate when he entered the dining-room a letter, which he saw by the writing was from one Neville-Smith. This sportsman had been in the Wrykyn eleven, and had left at the end of the previous summer for Cambridge. He had been at Spence’s while at school, and he and Jackson were close allies.

Jackson sawed off a foot or so of the loaf in front of him, bit a semi-circular section out of it, and turned his attention to the letter, with a view to ascertaining what Neville-Smith had got to say for himself.

It was a letter of some import. Neville-Smith, it seemed, home for the long vacation, was getting up a match between his village and the one next to it on the map. That is to say—for there is nothing like accuracy—between Bray Lench and Chalfont St. Peter’s.

To the uninitiated it will seem, perhaps, that this was not exactly a Test match. But mark! Round about Chalfont St. Peter’s there lived certain of the nobility and gentry. These had sons. And many of the sons knew how to play cricket. There would, to use the imagery of Jackson’s correspondent, be no flies on the Chalfont St. Peter’s eleven.

It behoved Neville-Smith to collect a hot side in order to beat them. The local curate was an old Blue, a bowler; and Neville-Smith himself had got his cap at Wrykyn as a bowler. So there would be nothing wrong with Bray Lench as far as that department of the game was concerned.

It was batsmen that Neville-Smith wanted.

He had two King’s men staying with him who had done well for the college, and he could get a few more moderate performers. But he wanted a touch of Class to set off the side, so would Jackson come down and play?

The match was fixed for the following Wednesday. Now, there was no school-match on that day; but Jackson knew very well that it was impossible to hope for leave to go and play in a village game twenty miles away. There would be nothing wrong or dangerous in it, but it would be unusual, and to the Wrykyn authorities everything unusual was anathema.

Jackson, however, determined not to refuse the invitation offhand. He would sleep on it in case there might be some way of accepting it which was not apparent to the casual observer. He had not found one by the morning. All he got by sleeping on it was a nightmare, in which he dreamed that he was just scoring heavily at Bray Lench when the opposition wicket-keeper suddenly turned into the Headmaster, and denounced him in full field.

But going over to school he met O’Hara, of Dexter’s. And, as O’Hara had frequently made useful suggestions in crises, he showed him Neville-Smith’s letter, and intimated that all contributions in the way of counsel would be thankfully received.

O’Hara read the letter through, and turned back to the first page to read it again.

“Ye’re all right,” he said, handing it back.

“Why? How?” said Jackson.

“Ye’re in the corps?”

“What’s that got to do with it?”

“Why, look at the address on the letter. Bray something or other, station Ealesbury. There’s a field day at Ealesbury on Wednesday.”

“Great Scott! So there is. And I was thinking of cutting it. But, half a second. I don’t quite see how it works out. I get to Ealesbury with the corps all right sometime in the morning, I suppose—about half-past eleven. Then what happens?”

“Do ye know the country round there? Find your way all right to Neville-Smith’s?”

“Oh, yes.”

“That’s all you want then. You’ll easily find a chance of falling out and cutting away. Then you nip off, have your match, and meet the corps at the station. You’ll have to take your chance of being spotted.”

“Oh, that’ll be all right,” said Jackson. “There’s always such a dickens of a crush and confusion at the station after a field day getting the chaps into the train that I shan’t be noticed. Thanks awfully, O’Hara. I’ll write to Smith to-night. He’ll have to lend me some things to play in, but I suppose he’ll be able to manage that.”

“If only I were in the corps,” said O’Hara, “I’d come too.”

“See what you miss,” said Jackson.

An answer to Neville-Smith’s letter left Wrykyn that evening. It set forth fully the difficulties and perils which must be encountered by flood and field, laid stress, however, on the fact that the master who acted as lieutenant in the school corps was astigmatic, and might be relied on not to notice a defection from the ranks, and strictly enjoined the recipient to render all possible help to the scheme. Above all, to meet the train at Ealesbury.

When the corps detrained on the following Wednesday they found waiting outside the station two other school corps, a detachment of the local volunteers, and Neville-Smith, wearing flannels and sitting in a neat dog-cart.

“We’re playing in our field,” said Neville-Smith to Jackson in the interval which took place between the departure of the train and the forming of the corps into a workable unit of the attacking force. “I got your letter. I’ve got some things for you to wear. Isn’t it a ripping day? There’ll be tea in the afternoon. It’s a big match. Everybody’s coming.”

Jackson grinned expansively. The word “tea” always stirred chords within his bosom.

“We’ve only got ten men at present,” continued Neville-Smith. “The curate’s promised to rout out another, though. Oh, by the way, you’ll go down on the score-sheet as Johnson. T. W. Johnson. Don’t forget. And I’ve told my people you’re a college friend of mine, and you’re just breaking your journey to London to play in the match.”

“Great Scott!” said Jackson plaintively. “I can’t remember all that. Say it again. Where did I start the journey I’ve broken?”

At this moment the excited voice of the Wrykyn sergeant-major was heard.

“Cum’ny—shun! Farm-farrs-’s-you-were-smartly-now-at-the-word-of-command-farm-farrs-kick-arch,” said the sergeant-major.

Jackson dived into his place, and the column moved off.

“I say,” said Neville-Smith, as Jackson left him, “I’ll follow you in the cart till you leave the road. Fall out as soon as you can, and you’ll find me waiting for you.”

It appeared that the army of which the Wrykyn corps formed a part was to trek across country in the direction of Chalfont St. Peter’s, which, for reasons of their own, the opposing force had occupied, and was resolved to hold. Chalfont St. Peter’s lay between Ealesbury and Bray Lench.

For half a mile the corps advanced down the road in fours, followed by Neville-Smith, or, to be sensational, Dogged by a Dog-cart! Then they turned through a gate into a wide gorse-covered common.

Jackson was in the rear-rank four, so that when he sat down and observed “Ow!” in a melancholy voice, he did not excite a great deal of attention.

“Something in my boot,” he explained, beginning to unlace his foot-gear.

Jackson sat where he was till the column had passed out of sound and sight. Then he made his way cautiously into the road. At the same moment a vigorous fusillade began in the woods at the far end of the common. The corps were in action.

“So they’ve got something to occupy their minds,” said Jackson, trotting down the road. “Now, where’s Smith got to?”

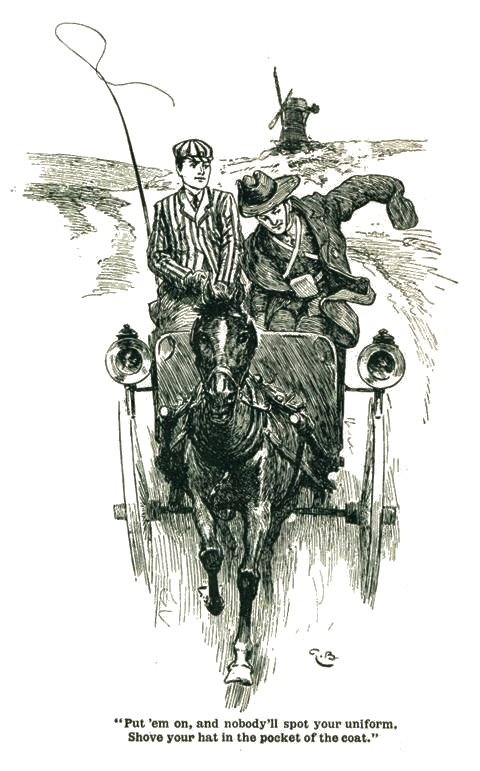

Neville-Smith was waiting a hundred yards from the gate. “Hop in,” he said. “Give us the rifle. Shove it against the seat. Good man, getting away so soon. We shall just be in time for the start. Now, then, Pickford,” he added encouragingly to the pony, “bustle about, and show what you’re made of.”

“I say,” said Jackson; “about this uniform: I mustn’t be seen. We can’t go in the front way. What shall we do?”

“That’s all right,” said Neville-Smith, “I thought of that. Reach behind you, and you’ll find a long dust-coat. I brought it on purpose; and there’s a King’s straw there, too. Put ’em on, and nobody’ll spot your uniform. Shove your hat in the pocket of the coat.”

“You’re a genius,” said Jackson joyfully, as he wriggled into the coat. “You think of everything. You’re a sort of—what’s the man’s name?”

“How should I know?” said Neville-Smith. “I tell you what you’ll be like if you spring about in this cart, and that is a man with a broken neck. You’ll be tumbling out if you aren’t careful.”

A drive of five miles through pleasant lanes brought them to the lodge gates of the Neville-Smith residence, and through the trees to the left Jackson caught an occasional cheering glimpse of white flannels, and heard the sound of bat meeting ball, as the two teams knocked about before the game.

Neville-Smith drove round to the back of the house, and they made their way to his bedroom by mysterious back stairs.

Having arrived at the room, Neville-Smith produced flannels and boots, and Jackson was soon out of his uniform, which had long since begun to be hot and uncomfortable, and arrayed in garments more suitable to the boiling day. He was lacing his last boot, when there was a grating of wheels on the drive outside.

Neville-Smith looked out.

“It’s the curate,” he said. “Good, he’s brought a man with him all right. Now the side’s complete. Come on.”

* * * * *

The sun was still shining gloriously, and it may be said at once that Jackson enjoyed his afternoon. It was an ideal day for cricket; the wicket was not terribly bad, and a gentle breeze tempered the heat sufficiently to make run-getting a pleasing occupation. Bray Lench won the toss, and Jackson accompanied Neville-Smith to the wickets. The bowling was of the sort usual at country-house cricket matches.

There was a long fast bowler and a short slow bowler. The fast bowler had four men in the slips, took a run of twenty yards, and sent down three full pitches to leg in his first three balls. Jackson, praising his luck, steered each of the trio to the extreme limit of the ground, to the marked discomfort of certain pheasants that were nesting in that neighbourhood.

With the slow bowler, who spent several minutes in arranging his field, and several more in sending down preliminary balls to the wicket-keeper, and then gave Jackson an innocuous long hop wide of the off-stump, he also took tea. The applause from the tent was soft and decorous, but frequent. Jackson had made a century off good bowling a week before, and was inclined to take liberties with the deliveries of Chalfont St. Peter’s.

Neville-Smith ran himself out, but Jackson, partnered by the curate, continued to worry the nesting pheasants. The eighth wicket fell with the score at sixty-one. By the exercise of immense care the last two men continued to stay in for a few overs, until Jackson had compiled eighty-three; then they succumbed, leaving Jackson not out with a very pretty innings to his credit.

He felt, as he walked back to the tent, that this was life as it should be lived. He had enjoyed his afternoon.

On Chalfont St. Peter’s going in to bat, the demon curate, the ex-Blue, performed prodigies with the ball. Jackson held a nice catch on the boundary; and wickets began to fall rapidly. A stand half-way through the innings caused some trouble, but once more Jackson held a lofty drive, and the one dangerous batsman of the enemy left with fifty-two to his credit.

It was now late in the afternoon, and Jackson, who, in his usual casual way, had hitherto not given the matter a thought, began to wonder when and how he was to rejoin his wandering fellow-Wrykinians. As far as he could remember from previous field-days, the train by which the corps returned was a late one. But it would not do to run the thing too fine. He would have to leave the field shortly.

* * * *

Just as the Chalfont St. Peter’s innings came to an end, a good twenty-five runs behind the Bray Lench total, there was borne on the breeze the noise of battle. The combatants were working round in the direction of the Neville-Smiths’ territory.

Jackson was eating a soothing ice apart from the crowd when a scrap of conversation between a new arrival and his hostess reached him.

“. . . . Yes, isn’t it? Awfully exciting. It’s a sham fight. And there are ever so many boys in blue waiting in that wood over there. We saw them. It’s an ambush, somebody said. And the other boys will march into the wood, and these boys will pounce out, and then the other boys will have lost. At least, Captain Mainwaring said so. I’ll get him to explain. He does it so well, you know. He was in South Africa, you know. Captain Main-waring. Mr. Neville-Smith wants to know . . . .”

Five minutes later Jackson was in Neville-Smith’s room, doing a rapid change of costume.

* * * *

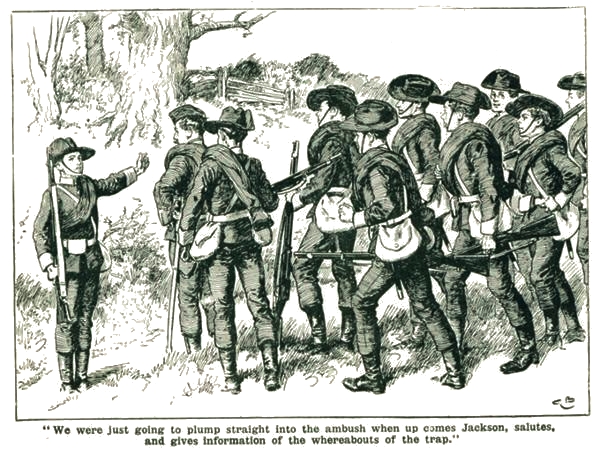

“You always say that Jackson is such a fool off the cricket-field,” said Mr. Templar, the lieutenant of the Wrykyn corps to another member of the staff in the common-room on the following day, when they were donning their gowns before prayers, “but you should have been with us yesterday. I tell you that boy can use his brains.”

Incredulous murmur from colleague.

“Yes, he can. He thinks for himself; and acts, too. It was the smartest bit of scouting I’ve ever seen,” continued Mr. Templar enthusiastically, for his heart was bound up with the corps. “But for him we should have been wiped out.

“It was like this. We were advancing. Main body of enemy here where this inkpot is. We were coming along here. This pen-holder shows our route. Well, just where I’ve put this box of nibs was a wood, and in it were hiding a large force of the enemy. We were just going to plump straight into the ambush when up comes Jackson, salutes, and gives the information of the whereabouts of the trap. How he got it without being captured I can’t think. They were hidden completely. He must have stalked them like an Indian.

“The curious thing is that he is not one of our regular scouts. In fact, I can’t remember sending him to scout at all. I must have done it, and forgotten. Anyhow, being prepared for the ambush, we moved up carefully, outflanked them, and captured every one of them. There were about two hundred. Of course, after that it was a walk over. I tell you that boy is not such a fool as he looks.”

“Hang it, Templar,” protested his colleague, “I never went so far as to accuse him of being that.”

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums