Royal Magazine, November 1904

“What they want, of course,” said Clowes, “is exercise.”

“They get out of that with their beastly doctor’s certificates,” said Trevor. “That’s the worst of this place. Any slacker who wants to shirk games goes to some rotten doctor in the holidays, swears he’s got a weak heart or something, and you can’t get at him. You have to sit and look on while he lounges about doing nothing, when he might be playing for the house. I bet Bellwood and Davies would both make good enough forwards if one could only get them on to the field. They’re heavy enough.”

“I don’t wonder, considering the amount they eat and the little exercise they take. I should say there was about twice as much of Bellwood as there ought to be. And he’s the sort of chap you don’t want more of than’s absolutely necessary.”

Study Sixteen was under discussion, not for the first time. Bellwood and Davies, its joint occupants, had been a thorn in Trevor’s side ever since he had become captain of football. It was bad enough that two such loafers should belong to the school. That they should be in his own house was almost more than he could bear.

It was his aim to make Donaldson’s the keenest and most efficient house at Wrykyn, and in this he had succeeded to a great extent. They had won the cricket cup, and were favourites for the football cup. Everyone in Donaldson’s was keen except Bellwood and Davies. They, sheltered behind doctor’s certificates, took life in their own slack way, and refused to exhibit any interest whatever in the doings of the house.

“It’s a rummy thing about that study,” said Clowes, “it’s always been like that. I believe anybody who’s a slacker or a bad lot goes there naturally; wouldn’t be happy anywhere else. Do you remember, when we first came to the house, Blencoe and Jones had it? They got sacked at the end of my first term. After that it was Grant and Pollock. They didn’t get sacked, but they ought to have been. Now it’s these two. Let’s hope they’ll keep up the tradition and get turfed out at their earliest convenience!”

“It makes me so sick,” said Trevor poking the fire viciously, “to think of two heavy chaps like that being wasted. They might make all the difference to the House second. We want weight in the scrum.”

In addition to the inter-house challenge cup there was a cup to be competed for by the second fifteens of the houses. Donaldson’s had a good chance of this, but were handicapped by a small pack of forwards. Seymour’s, their only remaining rival, were big and weighty. Clowes got up and stretched himself.

“Well,” he said, “I don’t think you’ll get much help from Bellwood and pard. They remind me of the man who slept well and ate well but who, when he saw a job of work, was all of a tremble. They won’t do a stroke if they can help it, and I don’t see how you can get them in the teeth of their certificates. Well, I must go and work. I like to do a Greek book unseen if possible, but the ‘Agamemnon’ is too tricky. I shall have to prepare it. By the way, have you got a copy to spare? I left mine over at school.”

“I’m afraid I’ve only got one, and I shall be wanting that. You can have it if you’ll give it up at half-past nine sharp.”

“No, it’s all right, thanks. I’ll borrow one from Dixon. He’s sure to have one. I believe he’s got every Greek play ever written.”

Clowes went off to Dixon’s study. Dixon was a mild, spectacled youth who did an astonishing amount of work, and was about as much of a hermit as anyone can be in a public-school house. He was nervous and anxious to oblige when he was not too deep in his own thoughts to understand what your request was.

“Hullo,” said Clowes, as he entered Dixon’s room, “this door seems pretty wobbly. What have you been doing to it?”

He moved it to and fro by way of illustration.

It was very rickety indeed. It was, in fact, almost off its hinges.

“I’m afraid it is a little,” assented Dixon. “The fact is, fellows have been running against it, and I think that has made it a little shaky.”

“Running against it!” said Clowes. “What did you do?”

“I—er—well, the fact is, I didn’t do anything. You see it was an accident. They told me themselves that it was.”

“It only happened once then? Must have taken a good strong chap to rush a door almost off its hinges at one shot.”

“No. They stumbled against it rather often.”

“Stumbled is good,” said Clowes. “I suppose they didn’t say how they came to stumble?”

“Oh, yes, they did. They tripped.”

“And you mean to say you believed that?”

“I couldn’t very well doubt their word,” expostulated Dixon.

Clowes smiled pityingly.

“I didn’t want to hurt their feelings,” Dixon went on.

Clowes smiled again.

“Who are the sensitive trippers?” he asked.

“Well, I don’t know that I ought to say, but I suppose it will be all right. They were Davies and Bellwood.”

“So I should have thought,” said Clowes. “How do you find that sort of thing affects your work?”

“Well, the fact is,” said Dixon eagerly, “I do find it a little hard to concentrate myself when I am continually interrupted by bangs on the door.”

“So should I. I think you’d get on better if you didn’t study Bellwood’s feelings so much. Do you mind if I borrow this ‘Agamemnon’ for a couple of hours? I’ve left mine over at the school, and we’ve got a beastly hard chorus to prepare for tomorrow.”

“Oh, certainly, do,” said Dixon. “Splendid play, isn’t it?”

“Not bad. I prefer ‘Charlie’s Aunt’ myself. Matter of taste, though. Thanks. I’ll return it before I go to bed.”

And he went back to his own study.

It was in the afternoons, after school, that Bellwood and his companion Davies found time hang so heavily on their hands. To lounge in one’s study and about the passages was pleasant for a while, but it was apt to pall in time, and then it was difficult to know how to fill in the hours.

On the afternoon following Clowes’s conversation with Dixon, Bellwood found things particularly slow. in ordinary circumstances he and Davies would have been at the school shop eating a heavy, crumpety tea. But today an unfortunate passage of arms with his form-master had led to that youth’s detention after school; and he was not yet out. Bellwood was one of those people who do not like to tea alone.

Besides, it was Davies’s turn to pay; and to go and have a meal at his own expense would have been so much dead loss.

So Bellwood haunted the house, feeling very much out of humour.

After wandering up and down the passage a few times and reading all the notices on the house notice board, it occurred to him that the half hour before the return of Davies might be well spent by ragging Dixon. It was for the purpose of keeping their betters from becoming dull, that people like Dixon were put into the world; and Dixon would in all probability be working—which would add a spice to the amusement.

He collected half-a-dozen football boots from the senior day-room. The rule of the house being that football boots were not to be brought into that room, there was always a generous supply there. Then he lounged off to Dixon’s study.

The door, as he had expected, was closed. He took a boot and flung it with accurate aim at one of the panels. There was a loud bang, and he grinned as he heard a chair pushed back inside the study and somebody jump up. That was all right, then. Dixon was at home.

He was stooping to pick up another missile, when the door opened. It was only when the second boot got home on the shin of the person who stood in the doorway, that he recognised in that person not Dixon, but Trevor. It was just here that he wished he had tried some other form of amusement that afternoon.

And, indeed, the situation was about as unpleasant as it could be. Even in moments of calm Trevor was a cause of uneasiness to Bellwood. And here he was unmistakably angry. It so happened that Bellwood’s boot had found its billet on the exact spot on which a muscular forward from Trinity College, Cambridge, had kicked Trevor in the match of the previous Saturday.

“Oh, I say, sorry,” gasped Bellwood.

“What the blazes are you playing at?” asked Trevor.

“I’m frightfully sorry,” said the demoralised Bellwood; “I thought you were Dixon.”

“And why should you fling boots at Dixon?”

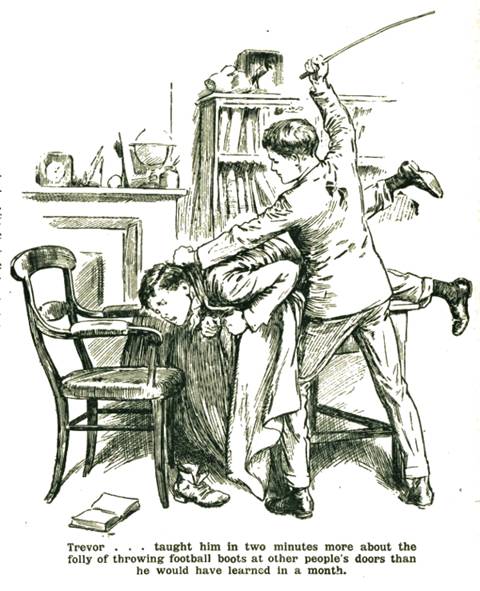

Bellwood, not feeling equal to the explanation that it was the mission in life of people like Dixon to have football boots thrown at them, remained silent; and Trevor, having summed up Bellwood’s character in an address in which the words “skunk, worm,” and “disgrace to the house,” occurred with what seemed, to the recipient of the terms, unnecessary frequency, dragged him into the study, produced a stick, and taught him in two minutes more about the folly of throwing football boots at other people’s doors than he would have learned in a month of verbal tuition.

Bellwood slunk away down the passage, and half-way to his own study met Davies, released from the form room and full of his grievances.

To judge from his remarks, Davies did not think highly of Mr. Grey, his form-master. Mr. Grey in his opinion, was a person of the manners-none-and-customs-horrid type. He had a jolly good mind, had Davies, to go to the Headmaster about it.

In a word, Davies was savage. Bellwood, eyeing his wrathful friend, was struck with an idea. Trevor’s stick had stung like an adder.

“Beastly shame,” he agreed, as Davies paused for breath. “It was jolly slow for me, too. I’ve been putting in the time having a lark with old Dixon. I can’t get him to come out, though I’ve been flinging boots. And his door won’t open. I believe he’s locked it.”

“Has he, by Jove!” muttered Davies, “we’ll soon see about that. Stand out of the way.”

He retired a few paces, and charged towards the door. Bellwood took cover in study twelve, the owner of which happened to be out, and listened.

He heard the scuffle of Davies’ feet as he dashed down the passage. Then there was a crash as if the house had fallen. He peeped out. Davies’ rush had taken the crazy door off its hinges, and he had gone with it into the study. He had a fleeting view of an infuriated Trevor springing from the ruins. Then, with Davies’s howl of anguish ringing in his ears, he closed the door of study twelve softly, and sat down to wait till the storm should have passed by.

At the end of a couple of minutes somebody limped past the door. The remnants of Davies, he guessed. He gave him a few moments in which to settle down. Then he followed, and found him in a dishevelled state in their study.

“Hullo,” he said artlessly, “what’s up? What happened? Did you get the door open?”

Davies glared suspiciously, scenting sarcasm, but Bellwood’s look of astonishment disarmed him.

“Where did you go to?” he enquired.

“Oh, I strolled off. What happened?”

Davies sat down, only to spring up again with a cry of pain. Bellwood recognised the symptoms, and felt better.

“I took the beastly door clean off its hinges. I’d no idea the thing was so wobbly.”

“Well, we ragged it a bit the other night, you remember. It was a little rocky then. Was Dixon sick?”

“Dixon! Why, Dixon wasn’t in there at all. It was Trevor—of all people! What the dickens was he doing there, I should like to know?”

Bellwood’s look of amazement could not have been improved upon.

“Trevor!” he exclaimed. “Are you sure?”

“Am I sure! Oh, you—!” words failed Davies.

“But what was he doing there?”

“That’s what I should like to know.”

It was really quite simple. Clowes had told the head of the house of Dixon’s painful case, and suggested that if he wished to catch Bellwood and his friend “on the hop,” as he phrased it, an excellent idea would be to change studies secretly with Dixon. This Trevor had done, with instant and satisfactory results. The ambush had trapped its victims on the first afternoon.

Study Sixteen continued to brood over its misfortunes.

“Beastly low trick changing studies like that,” said Davies querulously.

“Beastly,” agreed Bellwood.

“That worm Dixon must have been in it. He probably suggested it to Trevor. And now he’ll be grinning over it.”

This suspicion was quite unfounded. Dixon had probably never grinned in his life.

“I tell you what,” said Bellwood suddenly, “if they’ve changed studies, Dixon must be in Trevor’s den now. He’s always in the house at this time. He starts swotting directly after school. What’s the matter with going and routing him out and ragging him now? He wants it taken out of him for letting us down like that. Come on.”

“We’ll heave books at him,” said Davies with enthusiasm.

And the punitive expedition started.

Trevor’s study was in the next passage. They advanced stealthily to the door and listened. Somebody coughed inside the room. That was Dixon. They recognised the cough.

“Now,” whispered Davies, “when I count three!”

Bellwood nodded, and shifted a Hall and Knight’s algebra from his left hand to his right.

“One, two, three.”

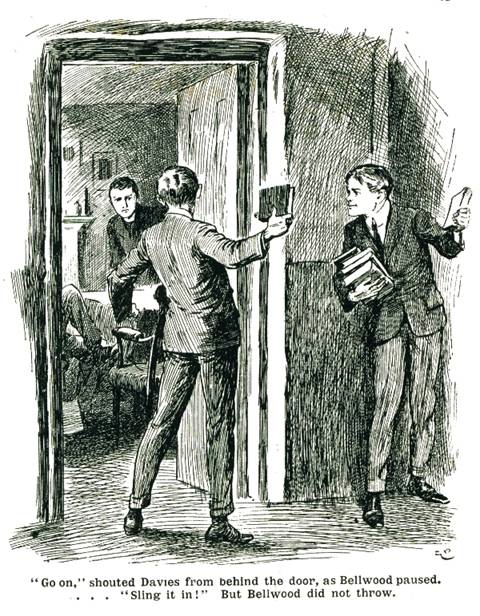

He turned the handle sharply, and flung open the door. At the same moment Bellwood discharged his algebra. It was a snapshot, but Dixon, sitting at the table outlined against the window, made a fine mark.

“Oh, I say!” cried Dixon, as the corner of the projectile took him on the ear.

“Go on,” shouted Davies from behind the door, as Bellwood paused with Victor Hugo’s “Quatrevingt-treize” poised. “Sling it in!”

But Bellwood did not throw. The book dropped heavily to the floor. Just as his first shot found its mark he had caught sight of Trevor, seated in a deck-chair by the window, reading a novel.

Finding Dixon’s study somewhat uncomfortable after Davies had removed the door, he had taken his book to his own den, where he could read in peace (so he thought) without disturbing Dixon’s work.

This third attack was the last straw. The matter had become too serious for summary treatment. He must think out a punishment that would fit the crime.

It flashed upon him almost immediately.

“Look here,” he said, “this is getting a bit too thick. You two chaps think you can do just as you like in the house. You’re going to find that you can’t. You’re no good to Donaldson’s. You shirk games. You do nothing but eat like pigs and make bally nuisances of yourselves. So you can just choose. I’m going out for a run in a few minutes. You can either come too, and get into training and play for the house second against Seymour’s, or you can take a touching-up in front of the whole house after tea.”

Davies and Bellwood looked blankly at one another. Could these things be? For three years they had grown up together like two daisies of the field: they had toiled not, neither had they spun. For three years the only form of exercise they had known had been the daily walk to the school shop. And here was Trevor offering them, as the sole alternative to a house licking, a beastly, violent run. And Trevor was celebrated for the length of his runs when he trained, and also for the rapidity of the same. The thing was impossible. It couldn’t be done at any price. Davies bethought him of the excuse which had stood by him so well for the past three years. This was just one of those emergencies for which it had been especially designed. But even as he spoke he could not help feeling that Trevor was not in just the proper frame of mind for medical gossip.

“But,” said Davies, “our doctor’s certificates. We aren’t allowed to play footer.”

“Doctor’s certificates! Rot! You’d better burn them. Well, are you coming for the run?”

Bellwood clutched at a straw.

“But we’ve no footer clothes,” he said.

“You’d better borrow some, then. If you aren’t back in this study, changed, by half-past five, you’ll get beans. Now get out.”

At ten minutes past five a tentative knock sounded on the door. Trevor opened it. There stood the owners of study sixteen garbed in borrowed football shirts and shorts.

Of the details of that run no record remains. The trio started off in a south-easterly direction, along the road which led to Little Poolbury. From this it may be deduced that the spin was not a short one. Whenever Trevor had chosen this direction for one of his training runs on previous occasions he had worked round through Little Poolbury to Much Wenham by road, then across difficult country (ploughed fields, brooks, and the like) to Burlingham, and then back to the school along the high road, the whole distance being between four and five miles. There is no reason for supposing him to have chosen another route on this occasion.

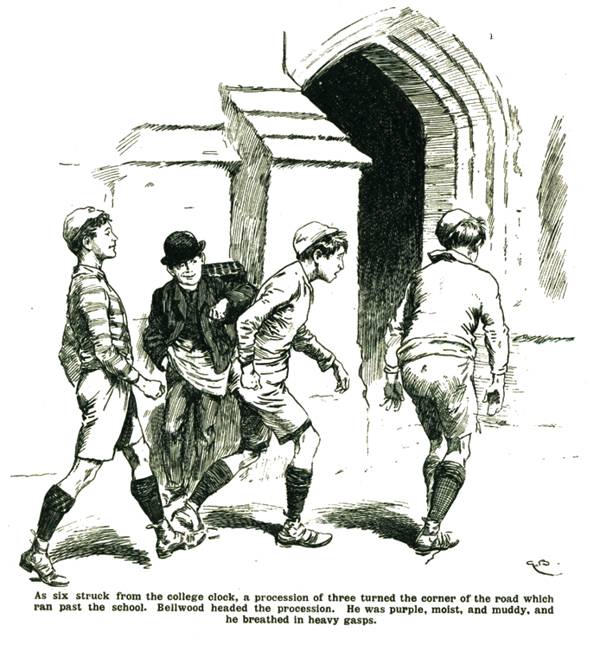

At any rate, as six struck from the college clock, a procession of three turned the corner of the road which ran past the school. Bellwood headed the procession. He was purple, moist, and muddy, and he breathed in heavy gasps. A yard behind him came Davies in a similar condition, if anything, a shade worse. At the tail of the procession came Trevor, who looked as fresh as when he had started. He wore a pleasant smile. They passed in at Donaldson’s gate, and were lost to view.

Study sixteen was subdued that night, but ate an enormous tea, and looked ninety per cent. fitter than it had done for years.

And in the last paragraph of the one hundred and eighteenth page of the eleventh volume of the “Wrykinian,” you will find these words to be written:—“Inter-House Cup (Second Fifteens), Final. Donaldson’s v. Seymour’s—This match was played on Saturday, March 10th, and resulted in a win for the former, after a good game by one goal and two tries to a penalty goal. For the winners Kershaw played well at half, and Smith in the centre. The pick of the forwards were Bellwood and Davies. The latter’s try was a clever piece of play. For Seymour’s . . .” But that’s all.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums