The Saturday Evening Post, May 31, 1924

CHAPTER III

THE library of Mr. Cooley Paradene at his house at Westbury, Long Island, was a room which caused bibliophiles on entering it to run round in ecstatic circles, prying and sniffing and uttering short, excited, whining noises like dogs suddenly plunged into the middle of a hundred entrancing smells. Its fame, one might say, was international, for articles describing it had appeared in such widely separated periodicals as the Atlantic Monthly, the Quarterly Review and the Mercure de France. On each wall were shelves, and on each shelf volume after volume of oddly ill-assorted sizes—here a massive tome, there next to it a squat dwarf of a book; yonder a thing that looked like a book, but was really a box containing a book. The mere sight of these affected those who appreciated that sort of thing like some powerful drug.

Bill, not being a bibliophile, bore the spectacle with more calm. On being shown into the library by Roberts, who informed him on his arrival at three o’clock that afternoon that Mr. Paradene would be disengaged shortly and desired him to wait, he made immediately for the curtained bow window, from which, as his previous visits to the house had told him, there was a view almost ideally arranged for the contemplation of one in his emotional state.

Beneath the window hung masses of laburnum, through which the observer might note and drink in the beauty of noble trees, a silver lake and a broad expanse of shady lawn. Just what a man in love wanted, held Bill.

There was but one flaw. The broad expanse of shady lawn was, he disgustedly perceived, marred at the moment by the presence of humanity, for which in his exalted condition he was in no mood. What he wanted was to contemplate Nature, and, contemplating, to muse dreamily upon Alice Coker. He resented the intrusion of an old man with a white beard and a small boy in knickerbockers. These two blots on the landscape were strolling up and down the middle of the nearest lawn, and they killed the whole beauty of the scene for Bill. However, at this moment they started to move toward the house, and presently the laburnum hid them and he was at peace again. He gave himself up once more to thoughts of Alice.

His reflections induced a sort of yeasty exhilaration, akin to—and yet how infinitely purer than—that which he had felt after the third of the powerful cocktails so jovially blended yestere’en by host Judson at his deplorable party. Of all the amazing things that could have happened, that he should actually have cast off the diffidence of months and asked her to marry him was surely the most amazing. No, not quite the most amazing. That dizzy niche was undoubtedly reserved for the astounding miracle that she should have received his proposal in so kindly a spirit. True, she had not actually committed herself to an engagement; but what of that? She had as good as said that, like some knight of old, he had merely to perform his allotted task and she would be his. What could be fairer than that? Oh, love! Oh, fire!

His meditations were interrupted by the opening of the door.

“Mr. Jasper Daly,” said the voice of Roberts.

From his post behind the curtains Bill heard a testy snort.

“What’s the sense of announcing me, my good man? There’s nobody here.”

“Mr. West was here a moment ago, sir.”

“Eh? What’s he doing here?”

Bill came out from his nook.

“Hullo, Uncle Jasper,” he said, and strove in vain to make his voice cordial.

After what had passed between Conscience and himself that morning, the spectacle of Mr. Daly was an affliction. The thought that it was even remotely possible that he in any way resembled this wizened, greedy-looking little person cut like a knife.

“Oh, there you are,” said Uncle Jasper grumpily, looking round with a pale reptilian eye.

“Mr. Paradene is engaged for the moment, sir,” said Roberts. “He will be with you shortly. Shall I bring you a cocktail, sir?”

“No,” said Uncle Jasper. “Never drink ’em.” He turned to Bill. “What you doing here?”

“Roberts called up this morning to say that Uncle Cooley wanted to see me.”

“Eh? That’s queer. I had a telegram yesterday myself saying the same thing.”

“Yes?” said Bill distantly.

He turned to look at the bookshelves. He was a broad-minded man and hoped that he could make allowance for the lowest of God’s creatures; but really it was almost indecent that one who had only recently left the golden presence of Alice Coker should have to endure the society of this old crumb. A moment later he had a fresh burden to bear. “Mrs. Paradene-Kirby,” proclaimed Roberts in the doorway.

The arrival of his Cousin Evelyn deepened Bill’s gloom. Even at the best of times she was hard to bear. A stout and voluminous woman in the early forties, with eyes like blue poached eggs, she had never had the sense to discard the baby talk that had so entertained the young men in her debutante days.

“O-o-h, what a lot of g’eat big booful books!” said Cousin Evelyn, addressing, apparently, the small fluffy dog which she bore in her arms. “Ickle Willie dog must be a good boy and not bite the books and maybe Uncle Cooley will give him a lovely cakie.”

“Mr. Otis Paradene and Master Cooley Paradene,” announced Roberts.

Bill now felt drearily resigned. To a man compelled to be in the same room with Uncle Jasper and Cousin Evelyn, the additional discomfort of Otis and little Cooley was negligible. Merely registering in his mind the opinion that Uncle Otis was fatter than ever and that little Cooley, a glistening child who had the appearance of having recently been boiled, looked like something that had come out of an egg, he turned to the bookshelves again.

“Great heavens!” cried Uncle Jasper, staring at the new arrivals, “is this Old Home Week? What you all doing here?”

“Cooley and I were specially telegraphed for,” replied Otis with dignity.

“Why, how puffickly straordinary!” said Cousin Evelyn. “So was I.”

“And he,” said Uncle Jasper, plainly bewildered, jerking a thumb at Bill, “had a phone call this morning. What’s the idea, I wonder?”

Cooley, a silent child, said nothing. He stood picking at the leather of an armchair with the nib of a pen, agitated at regular intervals by a hiccup that sounded like a diffident man starting to give three cheers for something and losing his confidence after the first “hip.” The rest of the family went into debate on the problem.

“How strange, Uncle Cooley asking us all to come here together like this,” said Cousin Evelyn.

Uncle Otis glanced about him cautiously and lowered his voice.

“If you ask me,” he said, “there’s something in the wind. My idea is that Cooley probably realizes that he’s getting pretty old, so he’s going to make settlements on us all.”

“Oh, do you really, really fink so?” exclaimed Cousin Evelyn rapturously. “Of course he is old, isn’t he? I always say that when a man has passed sixty he’s simply waiting for the end.”

“I was sixty-two last birthday,” said Uncle Otis coldly.

“Settlements?” said Uncle Jasper thoughtfully. He scratched his chin. “H’m—not a bad idea. Save us a lot of money on the inheritance tax.”

Bill could endure no more. Admitting that he was a bloodsucker—and Conscience had made this fact uncomfortably clear—he had at any rate always been grateful for blood received.

These ghouls seemed to have no decent human affections whatever.

“You people make me sick,” he snapped, wheeling round. “You ought to be put in a lethal chamber or something. Always plotting and scheming after poor old Uncle Cooley’s money!”

This unexpected assault from the rear created a certain consternation.

“The idea!” cried Cousin Evelyn.

“Impudent boy!” snarled Uncle Jasper.

Uncle Otis tapped the satirical vein.

“You’ve never had a penny from him, have you? Oh, dear, no!” said Uncle Otis.

Bill shot a proud and withering glance in his direction.

“You know perfectly well that he gives me an allowance, and I’m ashamed now that I ever let him do it. When I see you gathering round him like a lot of vultures——”

“Vultures!” Cousin Evelyn drew herself up haughtily. “I have never been so insulted in my life!”

“I withdraw the expression,” said Bill.

“Oh, well,” said Cousin Evelyn, mollified.

“I should have said leeches.”

The Paradenes were never a really united family, but they united now in their attack upon this critic. The library echoed with indignant voices, all speaking at once. It was only when another voice added itself to the din that quiet was restored.

It spoke, or rather shouted, from the doorway, and its effect on the brawlers was like that of a police whistle on battlers in a public street.

“Shut up!” bellowed this voice.

It was a voice out of all proportion to the size of its owner. The man standing in the doorway was small and slight. He had a red, clean-shaven face, a noble crop of stiff white hair, and he glared at the gathering through rimless pince-nez.

“A typical scene of Paradene family life!” he observed sardonically.

His appearance was the signal for another united movement on the part of the uncles and cousins. After a moment of startled pause, they surged joyfully toward him.

“ ’Lo, Cooley. Glad to see you”—Uncle Jasper.

“Welcome home, Cooley”—Uncle Otis.

“You dear man, how well you look!”—Cousin Evelyn.

Silence—Little Cooley.

More silence—Bill.

The man in the doorway seemed unappreciative of this deluge of affection. Now that he was no longer speaking, his mouth had set itself in a grim line, and the gaze he directed at the effusive throng through his rimless glasses might have damped more observant persons. The relatives resumed their exuberant greetings.

“I got your telegram, Cooley,” said Uncle Jasper.

“So did I,” said Cousin Evelyn. “And darling ickle Willie dog and me both thought it so cute and sweet of you to invite us.”

“Hope you had a good time, Cooley,” said Uncle Otis. “Lot of ground you’ve covered, eh?”

“How did you like Japan?” asked Cousin Evelyn. “I always say the Japanese are so cute.”

“We’ve missed you, Cooley,” said Uncle Jasper.

The taciturnity of his offspring in this time of geniality and rejoicing seemed to jar upon Otis. He dragged little Cooley away from the chair on which he was operating.

“Greet your dear uncle, boy.”

Little Cooley subjected that dispenser of largess to the stolid unwinking stare of boyhood.

“ ’Ullo!” he said in a loud, deep voice, and relapsed into a hiccup-punctuated silence again.

Uncle Jasper took the floor once more.

“Could you give me five minutes in private later on, Cooley?” he said. “I’ve a little matter to discuss.”

“I, too,” said Otis, “have a small favor to ask on little Cooley’s behalf.”

Cousin Evelyn thrust herself forward.

“Give g’eat big Uncle Cooley a nice kiss, darling,” she cried, extending the fluffy dog with two plump arms in the general direction of the benefactor’s face.

Mr. Paradene’s reserve was not proof against this assault.

“Take him away!” he cried, backing hastily. “So,” he said, “you aren’t satisfied with sponging on me for yourselves—started hunting me with dogs, eh?”

Cousin Evelyn’s face expressed astonishment and pain.

“Sponging, Uncle Cooley!”

Mr. Paradene snorted. His glasses fell off in his emotion and he replaced them irritably.

“Yes, sponging! I don’t know if you’ve taught that damned dog of yours any tricks, Evelyn; but if he can sit up on his hind legs and beg, he’s qualified for full and honorable standing in this family. That’s all any of you know how to do. I get back here after two months’ traveling, and the first thing you all do is hound me for money.”

Sensation.

Uncle Jasper scowled. Uncle Otis blinked. Cousin Evelyn drew herself up with the same hauteur which she had employed a short time before upon Bill.

“I am sure,” she said, hurt, “horrid old money is the last thing I ever think of.”

Mr. Paradene uttered an unpleasant laugh. Plainly he had come back from his travels in no mood of good will to all. This was a return to what might be called his early manner—that uncomfortable irritability which had made business negotiations with him so trying to the family in the days before he had been softened and mellowed by the collecting of old books.

“Yes,” he said bitterly, “the last thing at night and the first thing in the morning. I tell you I’m sick of you all—sick and tired! You’re just a lot of—of——”

“—— vultures,” prompted Bill helpfully.

“—— vultures,” said Mr. Paradene. “All so friendly and all so broke. For years and years you’ve done nothing but hang onto me like a crowd of——”

“—— leeches,” murmured Bill. “Leeches.”

“—— leeches,” said Mr. Paradene. “Ever since I can remember I have been handing out money to you—money, money, money. And you’ve absorbed it like so many——”

“—— pieces of blotting paper,” said Bill.

Mr. Paradene glared at him.

“Shut up!” he thundered.

“All right, uncle. Only trying to help.”

“And now,” resumed Mr. Paradene, having disposed of Bill, “I want to tell you I’ve had enough of it. I’m through—finished.” He eyed Bill dangerously for a moment, as if waiting to see if he had any synonyms to offer. “I called you together today to make an announcement. I have a little surprise for you all. You are about to acquire a new relative.”

The family looked at one another with a wild surmise.

“A new relative!” echoed Otis pallidly.

“Don’t tell me,” whispered Uncle Jasper in a bedside voice, “that you are going to get married!”

“No,” said Mr. Paradene, “I am not. The relative I refer to is my adopted son. Horace! Come here, Horace!”

Through the doorway there shuffled a small knickerbockered figure.

“Horace,” said Mr. Paradene, “let me present you to the family.”

The boy stared for a moment in silence. He was a sturdy, square-faced, freckled boy with short sandy hair and sardonic eyes. His gaze wandered from Uncle Jasper to Uncle Otis, from little Cooley to Cousin Evelyn, drinking them in.

“Is this the family?” he asked.

“This is the family.”

“Gee whistikers, what a bunch of prunes!” said the boy with deep feeling.

II

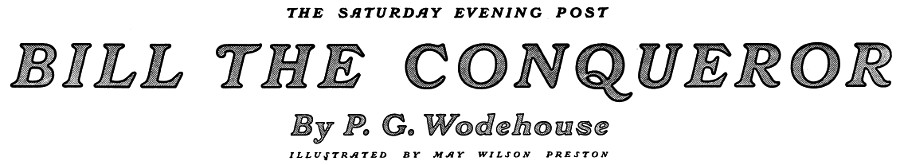

IN THE silence that followed this frank statement of opinion, another figure added itself to the group. This was a large and benevolent-looking man in a senatorial frock coat, whom Bill recognized by his white beard as the boy Horace’s companion on the lawn. Even from a distance this person had seemed venerable; seen at close range he achieved almost the impressiveness of a minor prophet. He was smiling a grandfatherly smile—the only smile of any description, it may be mentioned, on view in the room at that particular time; for a more joyless gathering it would have been hard to find at any spot in America where a funeral was not actually in progress. Uncle Jasper had sagged like a drooping lily, Uncle Otis’ eyes were bulging, Cousin Evelyn gave the impression of being about to burst. As for the boy Horace, the realization of the sort of family he had allowed himself to be adopted into seemed to have taken all the sunshine out of his life.

He was the first to speak, and his words revealed what was weighing upon his mind.

“Do I have to kiss them all?” he asked apprehensively.

“You are certainly not going to kiss me,” said Uncle Jasper definitely, waking from his stupor. He rounded on Mr. Paradene, puffing like a seal. “What is the meaning of this, Cooley?” he demanded.

Mr. Paradene waved a hand in the direction of the newcomer.

“Professor Appleby will explain.”

The minor prophet bowed. If he felt any embarrassment he did not show it. His smile, as he spoke, was as gentle and insinuating as ever.

“The announcement which my good friend Paradene——”

“How do you mean—your good friend Paradene?” inquired Uncle Jasper heatedly. “How long have you known him, I should like to know?”

“I met Professor Appleby on the train coming from San Francisco,” said Mr. Paradene. “It was he——”

“It was I,” said Professor Appleby, breaking gently in, “who persuaded Mr. Paradene to adopt this little lad here.” He patted the boy’s head and regarded his fermenting audience kindly. “My name,” he proceeded, anticipating Uncle Jasper, who seemed about to speak, “is possibly not familiar to you; but in certain circles, I think I may assert with all modesty, my views on eugenics are considered worthy of attention. Mr. Paradene, I am glad to say, has allowed himself to be enrolled among my disciples. I am a strong supporter of Mr. Bernard Shaw’s views on the necessity of starting a new race, building it with the most perfect specimens of the old. Horace here is a boy of splendid physique, great intelligence, sterling character and wonderful disposition. I hold—and I am glad to say that he agrees with me—that it is better for Mr. Paradene to devote his money to the rearing and training of such a boy than to spend it on relatives who—may I say—have little future and from whom he can expect—pardon me—but small returns. Mr. Paradene intends to found a family that looks forward instead of back; a family of—er—comers instead of a family of has-beens.”

The relatives gave tongue. All through this harangue they had been trying to speak, but Professor Appleby was not an easy man to interrupt. Now that he had paused, they broke out, Cousin Evelyn in the lead, Uncles Jasper and Otis following close behind.

“I never heard of such a thing in my life!”

“The fellow’s a dangerous crank!”

“Is it really possible that you intend to make this—this uncouth boy your heir rather than your own flesh and blood?”

Professor Appleby intervened gently.

“One must admit,” he acknowledged, “that Horace is at present a trifle unpolished. I quite see that. But what of it? A good tutor will remedy so small a defect in a few months. The main thing is that the little lad is superbly healthy and extremely intelligent.”

The little lad made no acknowledgement of these stately tributes. He was still wrestling with the matter nearest his heart.

“I will not kiss ’em,” he now announced firmly. “No, sir! Not unless somebody makes me a bet about it. I once kissed a goat on a bet.”

Cousin Evelyn threw up her hands, causing Willie-dog to fall squashily.

“What an impossible little creature!”

“I think, my dear Paradene,” said Professor Appleby mildly, “that, as the conversation seems to be becoming a little acrimonious, it would be best if I took Horace for a stroll in the grounds. It is not good for his growing mind to have to listen to these wranglings.”

Cousin Evelyn stiffened militantly.

“Pray do not let us disturb Horace in his home.” She attached a lead to Willie-dog’s collar and made for the door. “Good-by, Uncle Cooley,” she said, turning. “I consider I have been grossly and heartlessly insulted.”

“Hey!” exclaimed Horace, pointing. “You’ve dropped your knitting and it’s dragging!”

With one long, silent look of repulsion, Cousin Evelyn gathered Willie-dog into her arms and passed out. Uncle Jasper stumped to the door.

“Good-by, Jasper,” said Mr. Paradene.

“Good-by. I shall immediately take steps to have a lunacy commission appointed to prevent your carrying out this mad scheme.”

“And I,” said Uncle Otis—“I have only to say, Cooley, that the journey here has left me out of pocket to the extent of three dollars and seventy-nine cents. You shall hear from my lawyer.” He took little Cooley by the hand. “Come, John,” he said bitterly. “In future you will be known by your middle name.”

Horace observed this exodus with a sardonic eye.

“Say, I seem to be about as popular as a cold Welsh rabbit!” he remarked.

Bill came forward amiably.

“I’ve got nothing against you, buddy,” he said. “As far as I’m concerned, welcome to the family!”

“If that’s the family,” said Horace, “you’re welcome to ’em yourself.”

And placing his little hand in Professor Appleby’s, he left the room. Mr. Paradene eyed Bill grimly.

“Well, William?”

“Well, Uncle Cooley?”

“I take it that you have gathered the fact that I do not intend to continue your allowance?”

“Yes, I gathered that.”

His young relative’s calm seemed to embarrass Mr. Paradene a little. He spoke almost defensively.

“Worst thing in the world for a boy your age to have all the money he wants without earning it.”

“Exactly what I feel,” said Bill enthusiastically. “What I need is work. It’s disgraceful,” he said warmly, “that a fellow of my ability and intelligence should not be making a living for himself—disgraceful!”

Mr. Paradene’s sanguine countenance took on a deeper red.

“Very humorous!” he growled. “Very humorous and whimsical. But what you expect to gain by——”

“Humorous! You don’t imagine I was being funny, do you?”

“I thought you were trying to be.”

“Good Lord, no! Why, I came here this afternoon fully resolved to ask you for work.”

“You’ve taken your time getting round to it.”

“I didn’t get a chance to mention it before.”

“And what sort of work do you suppose I can give you?”

“A job in the firm.”

“What as?”

Bill’s extremely slight knowledge of the ramifications of the pulp-and-paper business made this a difficult question to answer.

“Oh, anything,” he replied with valiant spaciousness.

“I could employ you at addressing envelopes at ten dollars a week.”

“Fine!” said Bill. “When do I start?”

Mr. Paradene peered at him suspiciously through his glasses.

“Are you serious?”

“I should say so!”

“Well, I’m bound to say,” observed Mr. Paradene, after a pause, seeming a trifle disconcerted, “your attitude has taken me a good deal by surprise.” Bill thought of murmuring that his uncle did not realize the hidden depths in his character, but decided not to. “It’s an odd thing, William, but the only member of my family for whom I still retain some faint glimmer of affection is you.” Bill smiled his gratification. “And you,” boomed Mr. Paradene, “are an idle, worthless, good-for-nothing! Still, I’ll think it over. You’re not going back to the city at once?”

“Not if you want me.”

“I may want you. Stay here for another hour or so.”

“I’ll go and stroll by the lake.”

Mr. Paradene scrutinized him keenly.

“I can’t understand it,” he muttered. “Wanting to work! I don’t know what’s come over you. I believe you’re in love or something.”

III

FOR about a quarter of an hour after the parting of uncle and nephew perfect peace brooded upon Mr. Cooley Paradene’s house and grounds. At the end of that period Roberts the butler, agreeably relaxed in his pantry over a cigar and a tale of desert love, was startled out of his tranquillity by the sound of a loud metallic crash, appearing to proceed from the drive immediately in front of the house. Laying down cigar and book, he bounded out to investigate.

It was not remarkable that there had been a certain amount of noise. Hard by one of the colonial pillars the architect had tacked onto Mr. Paradene’s residence to make it more interesting lay the wreckage of a red two-seater car, and from the ruins of this there was now extricating itself a long figure in a dustcoat, revealed a moment later as a young man of homely appearance with a prominent arched nose and plaintive green eyes.

“Hullo,” said this young man, spitting out gravel. “How’s everybody?”

Roberts gazed at him in speechless astonishment. The wreck of the two-seater was such a very comprehensive wreck that it seemed hardly possible that any recent occupant of it could still be in one piece.

“Had a bit of a smash,” said the young man.

“An accident, sir?” gasped Roberts.

“If you think I did it on purpose,” said the young man, “prove it!” He surveyed the ruins interestedly. “That car,” he said sagely, after a prolonged scrutiny, “will want a bit of fixing.”

“How ever did it happen, sir?”

“Just one of those things that do happen. Coming up the drive at a pretty good lick when a bird settled in the middle of the fairway. Tried to avoid running over the beastly creature, and must have pulled the wheel too far round, because all of a sudden I skidded a couple of yards, burst a tire and hit the side of the house.”

“Good heavens, sir!”

“It’s all right,” said the young man reassuringly; “I was coming here, anyway.”

He discovered a deposit of gravel on his left eyebrow and removed it with a blue silk handkerchief.

“This is Mr. Paradene’s house, isn’t it?” he asked.

“Yes, sir.”

“Good! Is Mr. West here?”

“Yes, sir.”

“That’s fine! I wish you would tell him I want to see him. Coker’s the name—Mr. Judson Coker.”

“Very good, sir.”

Something in the butler’s manner, a certain placidity and lack of emotion, appeared to displease the young man. He frowned slightly.

“Judson Coker,” he repeated.

“Yes, sir.”

Judson looked at him expectantly.

“Name’s familiar, eh?”

“No, sir.”

“You don’t mean to say you’ve never heard it before?”

“Not to my knowledge, sir.”

“Huh!” said Judson.

He reached out a long arm and detained the receding Roberts by the simple process of seizing the tail of his coat. Even in his moods of normalcy there was never anything aloof and reticent about Judson Coker; he was always ready to chat anywhere at any time with anyone; and now his accident had brought about in him a still greater urge toward loquacity. Shocks affect different people in different ways. Judson’s had left him bubblingly confidential.

“Do you mean to tell me honestly, as man to man,” he demanded incredulously, “that you have never heard the name Judson Coker before?”

“No, sir.”

“Don’t you ever read Broadway Badinage?”

“No, sir.”

“Nor Town Gossip?”

“No, sir.”

The failure of this literacy test seemed to discourage Judson. He released the butler’s coat tail and relapsed into a moody silence.

“Shall I bring you a whisky and soda, sir?” asked Roberts.

It had come home to him by this time that the young visitor was not wholly himself, and remorse swept over him. Long ere this, he told himself, he should have been playing the part of a kindly physician.

The question restored Judson’s cheerfulness immediately. It was the sort of question that never failed to touch a chord in him.

“My dear old chap, you certainly may,” he responded with enthusiasm. “I’ve been wondering when you were going to lead the conversation round to serious subjects. Fix it pretty strong, will you? Not too much water and about the amount of whisky that would make a rabbit bite a bulldog.”

“Yes, sir. Will you step inside the house?”

“No thanks. Sit right here if it’s all the same to you.”

The butler retired, to return a few moments later with the healing fluid. He found his young friend staring pensively at the sky.

“I say,” said Judson, breathing a satisfied sigh as he lowered his half-empty glass, “coming back to that, you were kidding just now, weren’t you, when you said you didn’t know my name?”

“No, sir, I assure you.”

“Well, this is the most extraordinary thing I ever heard. You seem to know about as much of what’s going on in the world as a hen does of tooth powder. Didn’t you ever hear of the Silks?”

“Silks, sir?”

“Yes. The Fifth Avenue Silks.”

“No, sir.”

“Huh! Very famous walking club, you know. Used to assemble on Sunday mornings and parade up Fifth Avenue in silk pajamas, silk socks, silk hats, and silk umbrellas in case it rained. You really never heard of them?”

“No, sir.”

“Well, I’m darned! Doesn’t that just show you what fame is? I shouldn’t have thought there was an educated man in the country who hadn’t heard of the Silks. We got a whole page in three Sunday magazine sections the week the police stopped us.”

“Indeed, sir?”

“We certainly did—with a picture of me. I founded the Silks, you know.”

“Yes, sir?”

“Oh, yes; I’ve done a good deal of that sort of thing. I went up in an aëroplane once, scattering dollar bills over the city. I’m surprised you’ve not heard of me.”

“We live very much out of the great world down here, sir.”

“I suppose you do,” said Judson, cheered by this solution. “Yes, I guess that must be it. Quite likely you might not have heard of me if that’s so. But you can take it from me that I’ve done a lot of things in my time. Clever things, you know, that made people talk. If it hadn’t been for me I don’t suppose the custom of wearing the handkerchief up the sleeve would ever have been known in America.”

“Indeed, sir?”

“I assure you.”

To some men these reminiscences might have proved enthralling; but not to one who, like Roberts, was in the middle of Chapter XI of Sand and Passion and wanted to get back to it. He removed the decanter gently from the reach of Judson’s clutching hand and tactfully endeavored to end the conversation.

“I made inquiries, sir, and was informed that Mr. West was last seen walking in the direction of the lake. Perhaps if you would care to look for him there——”

Judson rose.

“You’re perfectly right,” he said earnestly; “absolutely right. I’ve got to see old Bill immediately. Came here specially to see him. No time to lose. Which way is this lake?”

“Over yonder, sir. . . . Ah, but here is Mr. West, coming up the drive.”

“Eh?”

“Mr. West, sir. Coming up the drive.”

And having indicated Bill’s approaching figure to the visitor, who was peering vaguely in every direction but the right one, Roberts withdrew into the house. He paused in the hall to telephone to the occupants of the local garage that there was man’s work for them to do in Mr. Paradene’s front garden, then returned to the pantry and resumed his reading.

It was the unwelcome arrival on its grassy shores of Professor Appleby and the boy Horace that had driven Bill from the lake. He was in no mood for conversation, for it had suddenly become plain to him that he had got to do some very tense thinking. Events since his coming to Mr. Paradene’s house had marched so rapidly that he had not had leisure until this moment to appreciate the problems and complexities with which life had filled itself. Brooding now upon these, he could see that fate had maneuvered him into a position where he was faced with the disagreeable necessity of being in two places at one and the same time. Obviously, if his newly displayed enthusiasm for toil was to carry weight, he must enter Uncle Cooley’s office immediately. Obviously, also, if he entered Uncle Cooley’s office immediately, he could not take Judson off for a fishing trip. If he went off now upon a fishing trip, what would Uncle Cooley think of him? And conversely, if he canceled the fishing trip, what would Alice Coker feel but that he had failed her in her hour of need after buoying her up with airy promises? Bill staggered beneath the burden of the problem, and was so preoccupied that Judson had to call him twice before he heard him.

“Why, hullo, Judson! What on earth are you doing here?”

He wrung the hand of the founder of the Fifth Avenue Silks with considerable animation. Since their somewhat distant talk on the telephone that morning his mental attitude toward Judson had changed a good deal. In his capacity of practically accepted suitor of Sister Alice, Bill had taken on a sort of large benevolence toward her entire family. He found himself glowing with brotherly affection for Judson, and even conscious of a certain timid desire to fraternize with the redoubtable J. Birdsey.

He massaged Judson’s shoulder lovingly. Quite suddenly it had come to him that the problem which had been weighing him down was no problem at all. He had been mistaken in supposing that two alternatives of action presented themselves. Now that the sudden spectacle of Judson had, so to speak, stressed the Coker motif in the rhythm of life, he saw clearly that there was only one course for him to pursue. At whatever cost to himself and his financial future, he must keep faith with Alice. The fishing trip was on, the spectacular entry into the pulp-and-paper business off.

“Hullo, Bill, o’ man,” said Judson. “Just the fellow I want to see. As a matter of fact, I came out here specially to see you. Had a bit of a smash,” he added, indicating the débris.

“Good heavens!” Bill quivered with a cold dismay at the thought of her brother having motor smashes. “You aren’t hurt?”

“No; just joggled a bit. Say, listen, Bill, Alice has been tipping me off about what’s happened at home. There’s no mistake about this fishing trip, is there? Because if there is I’m in very hollandaise. A week at the old lady’s would finish me.”

“That’s all right.” Bill patted his shoulder. “I promised Alice and that’s enough. The thing’s settled.” Bill hesitated blushfully for a moment. “Judson, old man,” he went on, his voice trembling, “I asked her to be my wife.”

“Breakfast every morning at 7:30 if you can believe it,” said Judson. “And working on the farm all day.”

“To be my wife,” repeated Bill in a slightly louder tone.

“And if there’s one thing that gives me the pip,” said Judson, “it’s messing about with a bunch of pigs and chickens.”

“I asked Alice to marry me.”

“And then family prayers, you know, and hymns and things. I couldn’t stand it, o’ man; simply couldn’t stand it.”

“She wouldn’t give me a definite answer.”

“Who wouldn’t?”

“Alice.”

“What about?”

Bill’s attitude of general benevolence toward the Coker family began to undergo a slight modification. Some of its members, he felt, could be a little trying at times.

“I asked your sister Alice to marry me,” he said coldly. “But she wouldn’t actually promise.”

“Well, that’s fine,” said Judson. “I mean, you can get out of it all right—what?”

Revolted as Bill was—and he gazed at his friend with a chilly loathing which might have wounded a more sensitive man—his determination was not weakened. Judson might have rather less soul than a particularly unspiritual wart hog, but he still remained Alice’s brother.

“Wait here,” he said stiffly. “I must go and see my uncle.”

“Why?”

“To tell him about this fishing trip.”

“Does he want to come, too?” asked Judson, perplexed.

“He wants me to go to work in his office at once, and I must tell him that it will have to be postponed.”

Mr. Paradene had left the study when Bill got there, but familiarity with his habits told Bill where to look. He found him in the library, perilously perched upon a long ladder, browsing on a volume which he had extracted from an upper shelf.

“Uncle Cooley.”

Mr. Paradene gazed down from the heights. He replaced the book and descended.

“I wanted to see you, William,” he said. “Sit down. I was just going to ring for Roberts to tell you to come here.” He lowered himself into the deep chair which had been the object of little Cooley’s recent attentions. “I have a suggestion to make.”

“What I wanted to say——”

“Shut up!” said Mr. Paradene.

Bill subsided. His uncle scrutinized him closely. There was something appraising in his glance.

“I wonder if you have any sense at all,” he said.

“I——”

“Shut up!” said Mr. Paradene.

He sniffed menacingly. Bill began to wish that he had some better news for this fiery little man than the information that he proposed to abandon the idea of work and go fishing.

“You’ve always been bone-idle,” resumed Mr. Paradene, “like all the rest of the family. But there’s no knowing whether you might not show some action if you were put to it. How would you like me to continue your allowance for another three months or so?”

“Very much,” said Bill.

“Mind you, you’d have to do something to earn it.”

“Certainly,” agreed Bill. “After I come back from this fishing——”

“I can’t go myself,” said Mr. Paradene meditatively, “and I ought to send someone. There’s something wrong somewhere.”

“You see——”

“Shut up! Don’t interrupt! This is the position: The returns of my London branch aren’t at all satisfactory. Haven’t been for a long time. Can’t make out why. My manager there struck me as a very shrewd fellow. Still, there’s no getting away from it, the profits have been falling off badly. I’m going to send you to London, William, to look into things.”

“London?” said Bill blankly.

“Exactly.”

“When do you want me to go?”

“At once.”

“But——”

“You’re wondering,” said Mr. Paradene, placing an erroneous construction on his nephew’s hesitation, “just exactly what I expect you to do when you get to London. Well, frankly, I don’t know myself, and I don’t quite know why I’m sending you. I suppose it’s just with the faint hope of discovering whether you have any intelligence at all. I certainly don’t expect you to solve a mystery that has been puzzling a man like Slingsby for two years.”

“Slingsby?”

“Wilfrid Slingsby, my London manager. Very capable man. I say I don’t expect you to go straight over there and put your finger on the solution of a problem that has baffled a man like Slingsby. All I feel is that if you keep your eyes open and try to learn something about the business and take an interest in its management, you may happen by luck to blunder on some suggestion which, however foolish in itself, might possibly give Slingsby an idea that would put him on the right track.”

“I see,” said Bill.

The estimate of his potentialities as factor in solving the firm’s little difficulties was not a flattering one, but he had to admit that it was probably more or less correct.

“It’ll be good training for you. You can go and see Slingsby and he can tell you something about the business. That will all help,” said Mr. Paradene with a chuckle, “when you come back here and start addressing envelopes.”

Bill hesitated.

“I’d like to go, Uncle Cooley——”

“There’s a boat on Saturday.”

“I wonder if I could have half an hour to think it over.”

“Think it over!” Mr. Paradene swelled ominously. “What do you mean, think it over? Do you understand that I am offering you——”

“Oh yes, I quite see that—it’s only—— Look here, let me just pop downstairs and speak to a fellow.”

“What are you talking about?” demanded Mr. Paradene warmly. “Why downstairs? What fellow? You’re gibbering!”

He would have spoken further, but Bill was already at the door. With a deprecating smile in his uncle’s direction, intended to convey the message that all would come right in the future, he edged out of the room.

“Judson,” he said, reaching the hall and looking about him.

He perceived that his friend was engaged at the telephone.

“Half a minute,” said Judson into the instrument. “Here’s Bill West. Just talking to Alice,” he explained over his shoulder. “Father’s come home and he says it’s all right about that trip.”

“Ask her to ask him if it will be as good if I take you over to London instead,” said Bill hurriedly. “My uncle wants me to go over there at once.”

“London?” Judson shook his head mournfully. “Not a chance! My dear old chap, you’re missing the whole point of this business. The idea is to dump me somewhere where I can’t——”

“Tell her to tell him,” urged Bill feverishly, “that I will pledge my solemn word that you shan’t have a cent of money or a drop of drink from the time you start to the day you get back. Say you’ll be just as safe in London with me as——”

Judson did not permit him to finish the sentence.

“Genius!” murmured he, a smile of infinite joy irradiating his face. “Absolute genius! I should never have had the gall to think up anything like that.” His face clouded again. “I doubt if it’ll work, though. Father’s not a chump, you know. Still, I’ll try it.”

There was a telephonic interval, at the end of which Judson relaxed and reported progress.

“She’s gone to ask him. But I doubt—I very much doubt—— Hullo?” He turned to the telephone again and listened for a space. He handed the instrument to Bill. “She wants to speak to you.”

Bill took the telephone with trembling hands.

“Yes?” he said devoutly. Impossible to say anything as coarsely abrupt as hello.

The musical voice of Alice Coker trilled at the other end of the wire.

“Who is that?”

“It’s me—er—Bill.”

“Oh, Mr. West,” said Alice, “I’ve been speaking to father about Judson going to London with you.”

“Yes?”

“He was very much against it at first, but when I explained to him that you would take such great care of Juddy——”

“Oh, I will! I will!”

“You really will see that he has no money at all?”

“Not a cent!”

“And nothing to drink?”

“Not a drop!”

“Very well, then, he may go. Thank you so much, Mr. West.”

Bill was beginning to try to put into neat phrases the joy he felt at the thought of doing the least service for her, but a distant click told him that his eloquence would be wasted. He hung up the receiver emotionally.

“Well?” said Judson anxiously.

“It’s all right.”

Judson uttered a brief whoop of ecstasy.

“Bill, you’re a marvel. The way you pulled that stuff about not letting me have any money! As solemn as a what-d’you-call-it! That was what turned the scale. As quick a bit of thinking as I ever struck,” said Judson with honest admiration. “Gosh, what a time we’ll have in London! There’s a place I’ve always wanted to see. All those historic spots you read about in the English novels, you know—Romano’s, the Savoy bar and all that. Bill, o’ man, we’ll paint that good old city bright scarlet from end to end.”

It became apparent to the horrified Bill that young Mr. Coker had got an entirely wrong angle on the situation. Only too plainly, it was shown by his remarks, the divine Alice’s deplorable brother had mistaken his recent promises for mere persiflage, evidently holding them to be nothing but part of a justifiable ruse to assist a pal. He choked.

“Do you really think,” he said slowly, struggling with his feelings, “that I would deceive that sweet girl?”

“You betcher!” said Judson sunnily.

For a long moment Bill eyed him in cold silence. Then, still without speaking, he strode off up the stairs to inform Mr. Paradene that his services were at his disposal.

IV

DOWN on the lawn that ran beside the lake Professor Appleby paced to and fro with the boy Horace. His white head was bent, and one viewing them from afar would have said that the venerable old man was whispering sage counsel into his young friend’s ears—words of wisdom designed to shape and guide his future life. And so he was.

“Now listen to me, kid,” he was saying, “and get this into your nut. I’ve got you in good and solid in this joint, and now it’s up to you. You don’t want to hang around here picking daisies. A nice quick clean-up, that’s what we want from you, young man.”

The boy nodded briefly. The minor prophet continued:

“It’s got to be an inside job, of course; but I’ll have Joe the Dip get in touch with you and stand by in case you need him. Not that the party’s likely to get rough if you only do your end of the thing without bungling it. Still, it’s as well to have Joe handy. So keep an eye out for him.”

“Sure!”

“And don’t go getting lazy just because you’re in soft in a swell home where you’ll probably have lots of good things to eat. That’s the trouble with you—you think too much of your stomach. If you were left to yourself you’d lie back in a chair stuffing yourself forever, without giving a thought to the rest of the gang. You can’t run a business that way. Just remember that we’re waiting outside and that what we want is quick action.”

“It’s no good rushing me,” protested Horace. “I mayn’t be able to do anything for weeks. Got to fix up a house party, haven’t I, so there’ll be lots of women around with joolry?”

Professor Appleby clutched his white beard in anguish.

“Gosh darn it,” he moaned, “are you really so dumb or are you just pretending? Haven’t I told you a dozen times that we aren’t after jewels this time? You don’t suppose a hermit like old Paradene gives house parties to women, do you? Didn’t I tell you till I was hoarse that what we want is those books of his?”

“I thought you were kidding,” pleaded Horace. “What’s the use of a bunch of books?”

“If you’ll just do as you’re told and not try to start thinking for yourself,” said Professor Appleby severely, “we may get somewhere. Those books may not look good to a little runt like you who doesn’t think of anything outside of what’s for dinner, but let me tell you that there isn’t one of them that isn’t worth four figures, and lots of them are worth five.”

“That so?” said Horace, impressed.

“It certainly is. And what you’ve got to do is to snoop around and find out just where the best of them are kept and then get away with them. See?”

“Sure!”

“It oughtn’t to be hard,” said Professor Appleby. “You’ve got the run of the place. Everything’s certainly working nice and smooth. The old man swallowed those references of yours hook, line and sinker.”

“Well, why wouldn’t he? Gee!” said Horace with feeling. “When I think of all the Sunday schools I’ve had to go to to get ’em!”

Professor Appleby frowned. The boy’s tone offended him.

“Horace,” he said chidingly, “you must not speak in that way. If you’re going to say a single word against your Sunday school I just won’t listen! Do you get me, you little shrimp, or have I got to clump you one on the side of the bean?”

“I get you,” said Horace.

Notes on the text may be found elsewhere on this site. Note that this serial episode corresponds to Chapter II, sections 3–6 of the book.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums