The Strand Magazine, April 1931

CHAPTER XII.

THE BISCUIT was a heavy-hearted young man when the omnibus set him down at the corner of Croxleigh Road, Valley Fields, shortly before eight-thirty p.m.

All through the long summer afternoon, starting about ten minutes after the conclusion of his interview with Mr. Hoke, his gloom had been deepening. And with reason.

“What,” J. B. Hoke had asked, in a fine passage, “is to prevent that red-headed young hound getting together some money and starting buying directly the market opens?”

The Biscuit could have informed him. The obstacle that stood between himself and anything in the nature of big buying in the market was the parsimony, the incredulity, the lack of broad vision displayed by his fellow human beings. Offered a vast fortune in return for open-handedness, they had declined to be open-handed. One and all they had shrunk from entrusting him with the loan that would enable him to invade the market on the morrow and cash in on the private information he had received concerning the imminent boom in Horned Toad Copper.

Breathing heavily, the Biscuit reached Mulberry Grove and turned in at the gate of The Nook. He wanted sympathy, and Berry Conway could supply it. The Biscuit tapped at the window of the sitting-room.

“Berry!” he called.

Berry was in, and he heard the tap. He also heard his friend’s voice. But he did not reply. He, too, was in the depths, and, much as he enjoyed the Biscuit’s society as a rule, he felt unequal to the task of chatting with him now. The Biscuit, he feared, would start rhapsodizing about his Kitchie, and every word would be a dagger in the heart. A man who has recently had his world shattered into a million fragments by a woman’s frown cannot lightly entertain happy lovers in his sitting-room.

So Berry crouched in the darkness, and made no sign. And the Biscuit, with a weary curse, turned away and sat on the front steps and smoked a cigarette.

Presently, finding no solace in nicotine, he rose and, going to the gate, leaned upon it. He surveyed the scene before him. Darkness was falling now, but the visibility was still good. A tall, thin man of ripe years had come round the corner and was regarding him as if he had been the tombstone of a friend.

“Good evening, Mr. Conway,” said this person. “This is Mr. Conway, I suppose? My name is Robbins.”

ii.

THE error into which the senior partner of the legal firm of Robbins, Robbins, Robbins, and Robbins had fallen was not an unnatural one. He had been dispatched by Mr. Frisby to Valley Fields to deal with an adventurer residing at The Nook, Mulberry Grove, and he had reached the gate of The Nook, and here was a young man standing inside looking out.

“I should be glad of a word with you, Mr. Conway,” he said.

“I’m not Mr. Conway,” the Biscuit said, curtly. “Mr. Conway’s out.”

Mr. Robbins held up a gloved hand. He had expected this sort of thing.

“Please!” he said. “I can readily imagine that you would prefer to avoid a discussion of your affairs, but I fear I must insist.”

Mr. Robbins spoke coldly, for he disliked the scoundrel before him.

“I represent Mr. Frisby, with whose niece, I understand, you are proposing to contract an alliance. My client is fully resolved that this marriage shall not take place, and I may say that you will gain nothing by opposing his wishes. An attitude of obduracy and defiance on your part will simply mean that you lose everything. Be reasonable, however, and my client is prepared to be generous. I think you will agree with me, Mr. Conway—here in camera, as one might say, and with no witnesses present—that the only aspect of the matter on which we need touch is the money aspect.”

The Biscuit had not allowed this address to be delivered without attempted punctuation. He had had far too much to put up with that afternoon to be willing to listen meekly to gibberers. However, he had endeavoured to speak, only to find the practised orator riding over him and taking him in his stride. Now that his companion had paused, and he had an excellent opportunity of reiterating that a mistake had been made, he did not seize it. The thought that at the eleventh hour Fate had sent him a man who talked about money—vaguely at present, but nevertheless with a sort of golden promise in his voice—held him dumb.

“Come now, Mr. Conway,” said Mr. Robbins, “are we going to be sensible?”

The Biscuit choked.

“Are you offering me money to——”

“Please!”

“Let’s get this straight,” said the Biscuit. “Is there or is there not money on the horizon?”

“There is. I am empowered to offer——”

“How much?”

“Two thousand pounds.”

Mulberry Grove swam before the Biscuit’s eyes.

“Yes, think it over,” said Mr. Robbins.

He adjusted his coat, draping it about him so as more closely to resemble a winding-sheet. The Biscuit leaned on the gate in silence.

“When do I get it?” asked the Biscuit at length.

“I have a cheque with me. See!” said Mr. Robbins, pulling it out and dangling it.

He had no need to dangle long.

“Gimme!” said the Biscuit, hoarsely, and snatched it from his grasp.

Mr. Robbins regarded him with a sorrowful loathing.

“I think I may congratulate the young lady on a fortunate escape,” he said, icily.

“Oh, ah,” said the Biscuit. “Yes. Thanks very much.”

Mr. Robbins gave up the attempt to pierce this armoured hide.

“Here is my card,” he said, revolted. “You will come to my office to-morrow and sign a letter which I shall dictate. I wish you good evening, Mr. Conway.”

He turned and walked away. His very back expressed his abhorrence.

The Biscuit stood for awhile gaping at the ornamental water. Then, walking slowly and dazedly to Peacehaven, he mixed himself the whisky and soda which the situation seemed to him so unquestionably to call for.

In the intervals of imbibing it, he sang joyously in a discordant but powerful baritone. The wall separating the sitting-room of Peacehaven from the sitting-room of The Nook was composed of one thickness of lath and plaster, and Berry Conway, wrestling with his tragedy, heard every note.

He shuddered. If that was how Love was making his neighbour feel, he was glad that he had been firm and had paid no attention to his knocking on the window.

iii.

IT was some twenty minutes later that the car containing Captain Kelly and his ally, Mr. Hoke, turned into Mulberry Grove.

“Here we are,” said the Captain. “Get out.”

Mr. Hoke got out.

“Now,” said Captain Kelly, having, in his military fashion, surveyed the terrain, “this is what we do, so listen, you poor sozzled fish. You go round to the back and stay there. I’ll stick here, in the front. And, remember, no one is to leave either of those two houses. And, if anyone goes in, they’ve damn’ well got to stay there. Do you understand?”

Mr. Hoke nodded eleven times with sunny good-will.

“Got gat,” he said.

CHAPTER XIII.

A DIET of large whiskies and small sodas, persisted in through the whole of a long afternoon and evening and augmented by an occasional neat brandy, is a thing which cuts, as it were, both ways. It had had the effect of bringing J. B. Hoke to the back-garden of The Nook with a revolver in his hand. But it had also had the effect of blurring Mr. Hoke’s faculties.

As he stood, propping himself up against The Nook’s one tree and breathing the sweet night air of Valley Fields, his mind was not at its best and clearest. He had a dim recollection of a confused conversation with his friend, Captain Kelly, in the course of which much of interest had been said; but it had left him in a state of uncertainty on three cardinal points.

These were:—

(a) Who was he?

(b) Where was he?

(c) Why was he?

To the solution of this triple problem he now proceeded to address himself.

Obviously, he felt, he must be there for some good purpose; and he fancied that, if he only remained perfectly quiet and concentrated, it would all come back to him.

So, for a space, Mr. Hoke stood and meditated on first causes.

Then he recollected. Everything was clear. The Captain had stationed him in this garden to prevent, by force if necessary, the exodus of young Conway and his red-headed friend.

Instinctively feeling that it would be sure to come in useful, J. B. Hoke had provided himself for this expedition with a large pocket-flask. He now produced this, and drank deeply of its contents. And his mood, which had begun by being one of amiable vacuity and had changed to one of self-pity, changed again. If somebody had come along and flashed a light on Mr. Hoke’s face at this moment, he would have perceived on it an expression of sternness. He was thinking hard thoughts of Berry and his friend. Trying to sneak out and slip something across a good man, were they? Ha! thought Mr. Hoke.

With a wide and sweeping gesture, designed to indicate his contempt for and defiance of all such petty-minded plotters, he flung an arm dramatically skywards. Unfortunately, it was the arm which ended in the hand which ended in the fingers which held the flask, and the fingers, unequal to the sudden strain, relaxed their grip. The next moment the precious object had vanished into the night, with its late owner in agonized pursuit.

For many long and weary minutes Mr. Hoke traversed the garden of The Nook from side to side and from end to end. He poked in bushes. He went down on hands and knees. He scrutinized flower-beds. But all to no avail. The garden held its secret well.

J. B. Hoke gave it up. He was beaten. Sadly he rose from the last flower-bed, and, turning, was aware that there was a light in one of the ground-floor windows, where before no light had been. Interested by this phenomenon, he hurried across the lawn and looked in.

The young man, Conway, was there, eating cold ham and drinking whisky.

Mr. Hoke, crouching outside the window, eyed him wistfully. He could have done with a slice of that ham. He could have used that whisky.

Suddenly he observed the banqueter stiffen in his chair and raise his head, listening. Mr. Hoke had heard nothing, and was not aware that the front-door bell had rung. But Berry had heard it, and a wild, reasonless hope shot through him that it was Ann, come to tell him that in spite of all she loved him still. The possibility was enough to send Berry shooting out of the door and down the hall. Mr. Hoke found himself looking into an empty room.

Empty, that is to say, except for the ham on the table and the whisky bottle beside it. These remained, and J. B. Hoke found in their aspect something magnetic, something that drew him like a spell. He tested the window. It was not bolted. He pushed it up. He climbed in.

WHAT with the tumult of his thoughts and the necessity of drinking his courage to the sticking-point, Mr. Hoke to-night had for perhaps the first time in his life omitted to dine, preferring to concentrate his energies on the absorption of double whiskies. He was now ravenously hungry, and he assailed the ham with a will. He also helped himself freely from the whisky bottle.

A man who is already nearly full to the top with mixed spirits cannot do this sort of thing without experiencing some sort of spiritual change. At the beginning of the meal, J. B. Hoke had been morose and particularly unkindly disposed towards Berry. By the time he had finished, a gentler mood prevailed. He was feeling extraordinarily dizzy, but with the dizziness had come a strongly-marked benevolence and a keen desire for the society of his fellows.

He rose. He went to the door. From the direction of the sitting-room came the buzz of voices. Evidently some sort of social gathering was in progress there, and he wanted to be in it.

He zigzagged down the passage, chose after some hesitation the middle one of the three handles with which a liberal-minded architect had equipped the sitting-room door, and, walking in, gazed on the occupants with a smile of singular breadth and sweetness.

There were two persons present. One was Berry. The other was a distinguished-looking man of middle life with a clean-cut face and a grey moustache. Both seemed surprised to see him.

“ ’lo!” said Mr. Hoke, spaciously.

Berry, in his capacity of host, answered him.

“Hullo!” said Berry. The apparition had not unnaturally startled him somewhat. “Mr. Hoke!”

Berry had now arrived at a theory which seemed to him to cover the facts. He assumed that after admitting Lord Hoddesdon a short while back he had forgotten to close the front door, and that his latest visitor, finding it open, had come in.

“Do you want to see me about something?” he asked.

“Got gat,” said Mr. Hoke, pleasantly.

“Cat?” said Berry.

“Gat,” said Mr. Hoke.

“What cat?” asked Berry, still unequal to the intellectual pressure of the conversation.

“Gat,” said Mr. Hoke, with an air of finality.

Berry tentatively approached the subject from another angle.

“Hat?” he said.

“Gat,” said Mr. Hoke.

He frowned slightly, and his smile lost something of its effervescent bonhomie. This juggling with words was giving him a slight, but distinct, headache.

Lord Hoddesdon, too, seemed far from genial. The interruption, coming at a moment when he had begun to talk really well, annoyed him.

Considering that he had stated so firmly and uncompromisingly to his sister Vera that nothing would induce him ever to return to Valley Fields, the presence of Lord Hoddesdon in Berry’s sitting-room requires, perhaps, a brief explanation. Briefly, he had changed his mind.

Lady Vera’s revelations on the previous night had shaken Lord Hoddesdon to the core. If Ann Moon was really planning to jilt his son and marry this Conway, the matter was serious. It had seemed to Lord Hoddesdon, always an optimist, that, once the girl was married to his son, he would surely be in a position to work Mr. Frisby for a small loan. It was vital, accordingly, that this Conway be firmly suppressed by one in authority.

Conscious, therefore, of the fact that he now had six hundred pounds in his account at the bank, he had come to The Nook to buy the fellow off. And he had just been in the act of talking to him as a head of the family should have talked, when this disgusting interruption had occurred.

Conscious that the spell had been broken and that further discussion of a delicate matter must be postponed, and feeling bitterly that this was just the sort of friend he might have expected the man Conway to have, Lord Hoddesdon rose.

“Where is my hat?” he said, stiffly.

“Gat,” said Mr. Hoke, his annoyance increasing. It seemed to him that these people were deliberately affecting to misunderstand plain English.

He regarded Lord Hoddesdon, now making obvious preparations for departure, with a hostile eye. For some little time he had been allowing his mind to wander from his mission, but now Captain Kelly’s words came back to him. “No one is to leave either of these houses,” the Captain had said. “And, if anyone goes in, they’ve damn’ well got to stay there.” This grey-moustached stiff had gone in. Very well. Now he would stay here.

“You thinking of leaving?” asked Mr. Hoke.

Lord Hoddesdon raised his eyebrows.

“I haven’t the pleasure of knowing who you are, sir——”

Berry did the honours.

“Mr. Hoke—The Earl of Hoddesdon.”

Mr. Hoke’s severity waned a little.

“Are you an Oil?” he said, interested.

“——but, in answer to your question, I am thinking of leaving,” said Lord Hoddesdon.

Mr. Hoke’s momentary lapse into amiability was over. He was the strong man again, the man behind the gun.

“Oh, no!” he said.

“I beg your pardon?” said Lord Hoddesdon.

“Granted,” said Mr. Hoke. He produced the gat, of which they had heard so much, and poised it in an unsteady but resolute grasp. “Hands up!” he said.

ii.

IN the sitting-room of Peacehaven, meanwhile, separated from the sitting-room of The Nook only by a thin partition, events had been taking place which demand the historian’s attention.

At about the moment when Mr. Hoke was climbing over the dining-room window-sill of The Nook, intent on ham and whisky, the Biscuit, seated in an arm-chair next door, had begun to gaze at a photograph of Miss Valentine on the mantelpiece, thinking the while those long, sweet thoughts which come to a young man with love in his heart and a cheque for two thousand pounds in his pocket. The burst of song in which he had indulged on returning home, after the departure of Mr. Robbins, had continued for the space of perhaps ten minutes. At the end of that period he had abated the nuisance and turned to silent musing. To him had been vouchsafed, in addition, one of the red-hottest tips that ever emanated from the Stock Market, and, as if that were not sufficient, a miraculous shower of gold which would enable him to profit by it.

Lavish. That is what the Biscuit considered it. Lavish. Nestling in his chair, he felt almost dizzy. Joy-bells seemed to be ringing in a world where everything, after a rocky start, had suddenly come abso-bally-right.

PRESENTLY, as he sat, there came to him the realization that on one point he had made a slight and pardonable error. Those were not joy-bells. What was ringing was the one at the front door. A caller had apparently come to share with him this hour of ecstasy. Hoping that it was Berry, fearing that it might be the Vicar, he went to the door and opened it. And, having opened it, he stood on the mat, staring with a wild surmise.

He had been prepared for Berry. He had been prepared for the Vicar. He had even been prepared for somebody selling brooms, cane-bottomed chairs, or aspidistras. What he had not been prepared for was his late fiancée, Ann Moon.

“Hul-lo!” said the Biscuit, blinking.

She was gazing at him with large eyes, and she seemed a little breathless. Her face was flushed, and her lips were parted. Extraordinarily pretty—not that it mattered, of course—it made her look, the Biscuit felt.

“Hullo! he said, blankly.

“Hullo!” said Ann.

“You!” said the Biscuit.

“Yes,” said Ann. “May I come in?”

“Oh, rather,” said the Biscuit, roused to the necessity of playing the host. “Of course. Certainly.”

Still stunned, he led the way to the sitting-room.

“Would you like to take a seat, or anything of that sort?”

Ann sat down, and there followed a pause of some length. It is not easy for a girl who has broken her engagement with a man, and who has called at his house to suggest that, her outlook on things having altered, that engagement shall be resumed, to know exactly how to start.

Ann’s mind, like that of her host, was in a distinctly disordered condition.

What made it so particularly difficult was that her mind was divided against itself. It was all very well for her to tell herself that she hated and despised Berry. So she did. But how long would this attitude last after the first spasm of righteous indignation had ceased to hold control? Lady Vera had said that Berry was a mercenary impostor, and a mercenary impostor he had proved.

So far, as the Biscuit would have said, so good.

But all the while there was something deep down in her which was whispering that, impostor or not, he was the man she loved and always would love. For years she had been plagued by a meddling and interfering Conscience; and, now that at last she seemed to be acting on lines of which Conscience approved, up popped an inconvenient subconscious self to make her uneasy. Look at it how you liked, it was a pretty tough world for a girl.

She forced herself to crush down this new assailant.

“Godfrey,” she said.

“Hullo?”

“I want to speak to you.”

“Shoot,” said the Biscuit.

“I——” said Ann.

She stopped. It was even more difficult than she had thought it would be.

Silence fell again. The Biscuit raked his mind for conversational material. He had always been fond of Ann, but he was bound to admit that he had liked her better before she contracted this lock-jaw or aphasia, or whatever it was. If Ann had come all the way to Valley Fields merely to gulp at him, he wished she would go.

As a matter of fact, he wished she would go, anyway. He was an engaged man, and an engaged man cannot be too careful. Kitchie might resent—and very properly resent—this entertaining of attractive females in his home.

However, he had to be courteous. It being impossible to take her by the scruff of the neck and bung her out, something in the nature of polite chit-chat was indicated.

“How are you?” he said.

“I’m all right.”

“Pretty well?”

“Yes, thanks.”

“You’re looking well.”

“You’re looking well.”

“Oh, I’m all right.”

“So am I.”

“That’s good,” said the Biscuit. “I wonder if you’d mind if I took a small snort? The old brain feels as if it had come a bit unstuck at the seams.”

“Go ahead.”

“Thanks. You?”

“No, thanks.”

“Well, best o’ luck,” said the Biscuit, imbibing.

He felt more composed now. It occurred to him that a major mystery still remained unsolved.

“How did you know I was living here?” he asked.

“Lady Vera told me.”

“Ah!” said the Biscuit. “I see. She told you?”

“Yes. By the way, did she tell you?”

“That I live here?”

“About her engagement.”

The Biscuit goggled.

“Her engagement?”

“She’s going to marry my uncle.”

“What! Old Pop Frisby?”

“Yes.”

“My stars!”

“I was surprised, too. I hadn’t thought of Uncle Paterson as a marrying man.”

“Any man’s a marrying man that a woman like my Aunt Vera gets her hooks on,” said the Biscuit profoundly. “Well, I’m dashed! So my family is keeping your family in the family, after all.”

He mused awhile. Things were growing clearer.

“So that’s why you came down here?”

“No.”

“You mean, you didn’t come here just to tell me this bit of news?”

“No.”

“Then why,” demanded the Biscuit, putting his finger squarely on the centre of this perplexing matter, “did you come? Always glad to see you, of course,” he added, gallantly. “Drop in any time you’re passing, and all that. Still, why did you come?”

Ann felt that the moment had arrived.

“Godfrey,” she said.

“Carry on,” said the Biscuit encouragingly, after an adequate pause.

“Godfrey,” said Ann, “you got a letter from me, didn’t you?”

“Breaking the engagement? Rather.”

“I came here,” said Ann, “to tell you I was sorry I wrote it.”

The Biscuit was insufferably hearty.

“Not at all. A very well-expressed letter. Thought so at the time and think so still. Full of good stuff.”

“I——”

The Biscuit clicked his tongue remorsefully.

“By the way,” he said, “can’t think what I was doing, not touching on the topic before, but wish you happiness, and all that sort of rot. Berry Conway told me you and he had signed up.”

“Do you know him?” cried Ann, astonished.

“Of course I know him. And I ought to have extended felicitations and so forth long ago. What with life being tolerably full, and one thing and another, I overlooked it. Dashed sensible of you both, I consider. There’s no one I would rather see you engaged to than old Berry.”

“We are not engaged.”

“Not?”

“No.”

“Then,” said the Biscuit, aggrieved, “I have been misinformed. My leg has been pulled, and—what makes it worse—by a usually reliable source.”

“I’ve broken it off,” said Ann shortly.

The Biscuit stared.

“Why?”

“Never mind why.”

“My dear old soul,” said the Biscuit, paternally, “I would be the last man to butt in on other people’s affairs, but, honestly, don’t you think you’re rather overdoing this breaking-off business? I mean to say, twice in under a week.”

Ann clenched her hands.

“It needn’t be twice,” she said, speaking with difficulty, “unless you like.”

“Eh?”

“I came here,” said Ann, “to suggest that, if you felt the same, we might consider that letter of mine not written.”

The Biscuit gasped. They were coming off the bat too quick for him to-day. First Hoke, then old Robbins, and now this. He began to feel slightly delirious.

“Do you mean,” he asked, “that you’re suggesting that you and I——”

“Yes.”

“That our engagement——”

“Yes.”

“That we shall——”

“Oh, yes, yes, yes!” said Ann.

THERE was a long silence. The Biscuit walked to the window and looked out. There was nothing to see, but he remained there, looking, for some considerable time. He perceived that all his tact and address would be needed to handle this situation.

“Well?” said Ann.

“Well?” said Ann.

The Biscuit turned. He had found the right words.

“Look here, old soul,” he said apologetically, “I’m afraid I’ve a rather nasty knock for you, and, if you take my advice, you’ll have a drink to brace yourself. I’d do anything in my power to oblige, but the fact is, I can only be a sister to you.”

With a sorrowful jerk of the thumb, he indicated the mantelpiece.

“Like Dykes, Dykes, and Pinweed,” he said, “I’m bespoke.”

Ann caught her breath in sharply.

“Oh!” she said.

She got up. Never had she felt so supremely foolish; but she held her head high. She went to the mantelpiece and examined the photograph thoughtfully.

“Why, I know her!” exclaimed Ann.

“You do?”

“It’s Kitchie Valentine. I came over in the boat with her.”

The Biscuit had half a mind to say something about this bringing them all very close together, but he was not quite sure how it would go. It might go well, or it might not go well. He decided to keep it back.

“She lives next door, doesn’t she?” said Ann. “I had forgotten.”

“That’s right,” said the Biscuit. “Next door. We did most of our coo-and-billing across the fence.”

“I see. Well, I hope you’ll be very happy.”

“Oh, I shall,” the Biscuit assured her.

“I think I’ll be going,” said Ann.

The Biscuit held up a compelling hand.

“Wait!” he said. “Just one moment. I want to get to the bottom of this business of old Berry.”

“I don’t want to talk about him.”

“This lovers’ tiff——”

“It wasn’t a lovers’ tiff.”

“Then what was it? Good heavens!” said the Biscuit, warming to his subject, “if ever there were a couple of birds made for one another, it’s you and Berry. I mean to say, you’re one of the sweetest things on earth, and he’s a corker. If you’ve really gone and given old Berry the push, you must be cuckoo. You won’t find another fellow like Berry in a million years. He’s all right. And what they think of him in the Secret Service!” added the Biscuit, belatedly remembering. “The blokes up top have got their eye on him all right, I can tell you!”

Ann laughed shortly.

“Secret Service!”

“Why,” asked the Biscuit, “do you say ‘Secret Service’ in that nasty, tinkling voice?”

“I know all about him, thanks,” said Ann. “There’s no need for you to lie to me. He did all of that that was necessary.”

“Oh?” said the Biscuit reflectively. “Oh, ah! Ah! Oh!”

He began to understand.

“He’s my uncle’s secretary,” said Ann, with scorn.

“In a measure,” admitted the Biscuit reluctantly, “yes. But,” he went on, brightening, “what of it?”

“What of it?”

“What difference does it make?”

Ann’s eyes blazed.

“You don’t think it makes any difference? You don’t think that a girl’s feelings are likely to change towards a man when she finds he has been lying to her and making a fool of her and pretending to be fond of her just because——” she choked—“just because she happens to be rich?”

The Biscuit was shocked.

“My dear young prune,” he said, “you aren’t asking me to believe that you think that a fellow like Berry was after your money?”

“Yes, I am. Lady Vera said he was.”

“Admitting,” said the Biscuit, “that what my Aunt Vera doesn’t know about cash-chivvying isn’t worth knowing, I deny it in toto. Aunt Vera was talking through her hat. Listen, you poor mutt. I was at school with old Berry for a matter of five years, and I know him from caviare to nuts. He’s the squarest bird on earth. And that’s official. You don’t suppose a man can be mistaken about another man after five years at school with him, do you? Berry’s all right.”

“Then why did he lie to me?”

“I’ll tell you about that,” said the Biscuit. “Give you a good laugh, this will. He saw you at the Berkeley that day and fell in love with you, and then he saw you in your car, and the only way he could think of to get to know you was to jump in and say he was a Secret Service man. That’s the sort of chap he is. Weak in the head, but fizzing with romance. And let me tell you something, and you’ll see what a young muttonhead you’ve been to think that it was your money he was after. He’s got money himself, thousands and thousands of pounds of it. Or he will have to-morrow. Me, too. We’ve come into a fortune.”

Ann was silent. Then she drew her breath in with a long sigh.

“I see,” she said.

“It’s no good saying you see. What are you going to do about it?”

“I’ve made a fool of myself,” said Ann.

“You’ve made a gosh-awful fool of yourself,” agreed the Biscuit, enthusiastically. “What steps, then, do you propose to take?”

“Shall I write to him?”

“Not a bad idea.”

“I’ll go home and do it now.”

“Excellent.”

“Well, I’ll be going, Godfrey.”

“Perhaps it would be as well,” said the Biscuit. “I mean, delighted you were able to come, and so on, but you know how it is.”

“I suppose I ought to try to thank you,” said Ann, at the front door.

“Not a bit necessary. Only too pleased if any little thing I may have said has been instrumental——”

“Well, good-bye.”

“Good-bye,” said the Biscuit. “I shall watch your future career with considerable interest. Hullo, who’s this bird?”

The bird alluded to was the redoubtable Captain Kelly, who had suddenly manifested himself out of the darkness and intruded on this farewell.

“Just a moment,” said Captain Kelly.

Ann stared at him, alarmed. With his hat pulled down over his eyes, the Captain was a disquieting figure.

“All hawkers, bottles, and street cries should go round to the back door,” said the Biscuit, with a householder’s austerity. “Unless, by any chance,” he said, an alternative theory crossing his mind, “you’re the Vicar?”

“I’m not the Vicar.”

“Then who are you?”

“Never mind who I am,” said Captain Kelly, shortly. “All I want to say is that you don’t leave here to-night, and this young lady doesn’t leave here to-night.”

“What?” cried the Biscuit.

“What?” cried Ann.

“See this?” said the Captain.

The light from the hall shone on a businesslike-looking revolver. Ann and the Biscuit gazed at it, fascinated.

“I’ll be waiting outside if you try any funny business,” said Captain Kelly.

“But what’s it all about?” demanded the Biscuit.

“You know what it’s all about,” said the Captain, briefly. “In you get, now, and don’t you try to come out, unless you want the top of your head blown off. I mean it.”

Inside the hall, the Biscuit stared at the closed door as if he were trying to see through it.

“The suburbs for excitement!” he said.

Ann uttered an exclamation.

“But I can’t stay here all night,” she cried.

The Biscuit quivered as if an electric shock had passed through him.

“You jolly well bet you can’t!” he agreed, vehemently. “I don’t know if you happen to know it, but poor little Kitchie’s faith in man is pretty wobbly these days. She had a bad shock not long ago, administered by a worm of the name of Merwyn Flock. If she finds that you and I have been camping out here—— My gosh!” groaned the Biscuit, “all will be over. No wedding bells for me. She’s as likely as not to go into a convent or something.”

“But what’s to be done? Who is that man?”

“I don’t know. No pal of mine.”

“He must be mad.”

“He’s absolutely potty. But that doesn’t make it any better. Did you see that gun?”

“Well, what are you going to do?”

“Take another small snort.”

He led the way back to the sitting-room, and reached abstractedly for the decanter. He was thinking—thinking.

iii.

THE actions of both Captain Kelly and J. B. Hoke had been, as we have seen, dictated by careful and reasonable reflection. They were based on solid common-sense. Yet, just as Ann and the Biscuit, in the sitting-room of Peacehaven, had come to the conclusion that the Captain was unbalanced and even potty, so now did Berry and Lord Hoddesdon, on the other side of the partition, take a snap judgment and condemn Mr. Hoke on the same grounds.

Lord Hoddesdon was the first to clothe this thought in words. He had been watching Mr. Hoke’s pistol with a fascinated eye and a sagging jaw, and now he spoke.

“Who is this lunatic?” he asked.

Berry was more soothing.

“It’s quite all right, Mr. Hoke,” he said. “You’re among friends. You remember me, don’t you? Conway?”

“The man’s a raving madman,” proceeded Lord Hoddesdon. “Keep your dashed finger off that trigger, sir, confound you!” he added, with growing concern. “The thing will be going off in a minute.”

“Hands up!” said Mr. Hoke, muzzily.

“Our hands are up,” said Berry, still with that same elder-brotherly sweetness. “You can see they’re up, can’t you? Look! Right up here.”

And, to emphasize the point, he twiddled his fingers. Mr. Hoke stared at them with an air of dislike, blinked, and rose to a point of order.

“Hey!” he observed. “Quit that!”

“Quit what?”

“That twiddling,” said Mr. Hoke. “I don’t like it.”

It reminded him somehow of spiders, and he did not wish to think of spiders.

“I’ll tell you what,” said Berry; “put that pistol away and just sit back quite quietly, and I’ll go and make you a nice cup of tea.”

“Tea?”

“A nice, hot, strong cup of tea. And then we’ll all sit down and have a good talk, and you shall tell us what it is that’s on your mind.”

Mr. Hoke regarded him owlishly. He seemed to be considering the suggestion.

“I had a mother once,” he said.

“You did?” said Berry.

“Yes, sir!” said Mr. Hoke. “That’s just what I had. A mother.”

“The man’s a dashed, drivelling, raving, raging lunatic,” said Lord Hoddesdon.

Mr. Hoke started. Something in his lordship’s words had caused a monstrous suspicion to form itself in his clouded mind. It seemed to him, if he had interpreted them rightly, that Lord Hoddesdon was casting doubts on his sanity. He resented this.

“Think I’m crazy?” he said.

“Not crazy,” said Berry. “Just——”

“He’s as mad as a hatter,” insisted Lord Hoddesdon, who objected to paltering with facts and liked to call a spade a spade. “Will you stop fingering that trigger, sir? Do you want a double murder on your hands?”

“I’m not crazy,” said Mr. Hoke. “No, sir.”

“I’m sure you’re not,” said Berry. “Just the tiniest bit over-excited. Why not lay that pistol down—look, there’s a table where it would go nicely—and tell us all about your mother.”

Mr. Hoke’s mind was still occupied with his grievance. He objected to this attempted side-tracking of the conversation to the topic of mothers. Plenty of time, he felt, to talk about mothers when he had proved to these sceptics that he was as sane as anybody. He proceeded to give his proofs.

“You want to know why I’m acting this way?” he said. “You don’t know, do you? Oh, no, you don’t know. Can’t imagine, can you? That red-headed pal of yours hasn’t been telling you what I told him about The Dream Come True, has he? Oh, no. He hasn’t come and handed you the dope, has he? Oh, no. You and your mothers! Don’t try to put me off by talking about your mother, because I know what I’m doing, and if your mother doesn’t like it, she can do the other thing.”

TO Lord Hoddesdon, chafing impotently, these strong remarks on the subject of dreams and mothers seemed but further evidence, if such were needed. Gibbering, pure and simple, his lordship considered Mr. Hoke’s last speech. But to Berry there came dimly, as through a fog, a sort of meaning.

“What about The Dream Come True?” he asked.

“You don’t know, do you?” asked Mr. Hoke, witheringly.

He moved cautiously across the room, the better to keep his eye upon his prisoners; and sat with his back against the wall, surveying them keenly.

“You don’t know, do you?” he said. “That red-head didn’t tell you, did he? And you weren’t listening outside old Frisby’s door that day, when him and me were talking about keeping it under our hats that there had been a new reef located? Well, if you think you’re going to get up to London to-morrow and start in buying Horned Toad stock, you’ve another guess coming. You’re going to stay right here, that’s what you’re going to do.”

He turned a glazing eye on Lord Hoddesdon.

“And that goes for you, too, Oil,” he said.

Berry uttered a sharp cry. What Mr. Hoke’s maunderings about the Biscuit meant, he was unable to gather: but from the welter of the other’s words there had emerged the broad, basic fact that The Dream Come True had been a valuable property after all.

A wave of helpless fury flooded over him.

“So you knew there was copper there?” he cried.

“Knew it all along,” said Mr. Hoke. “And I’m going to clean up big. You’ll see Horned Toad up in the hundreds before the end of the week.”

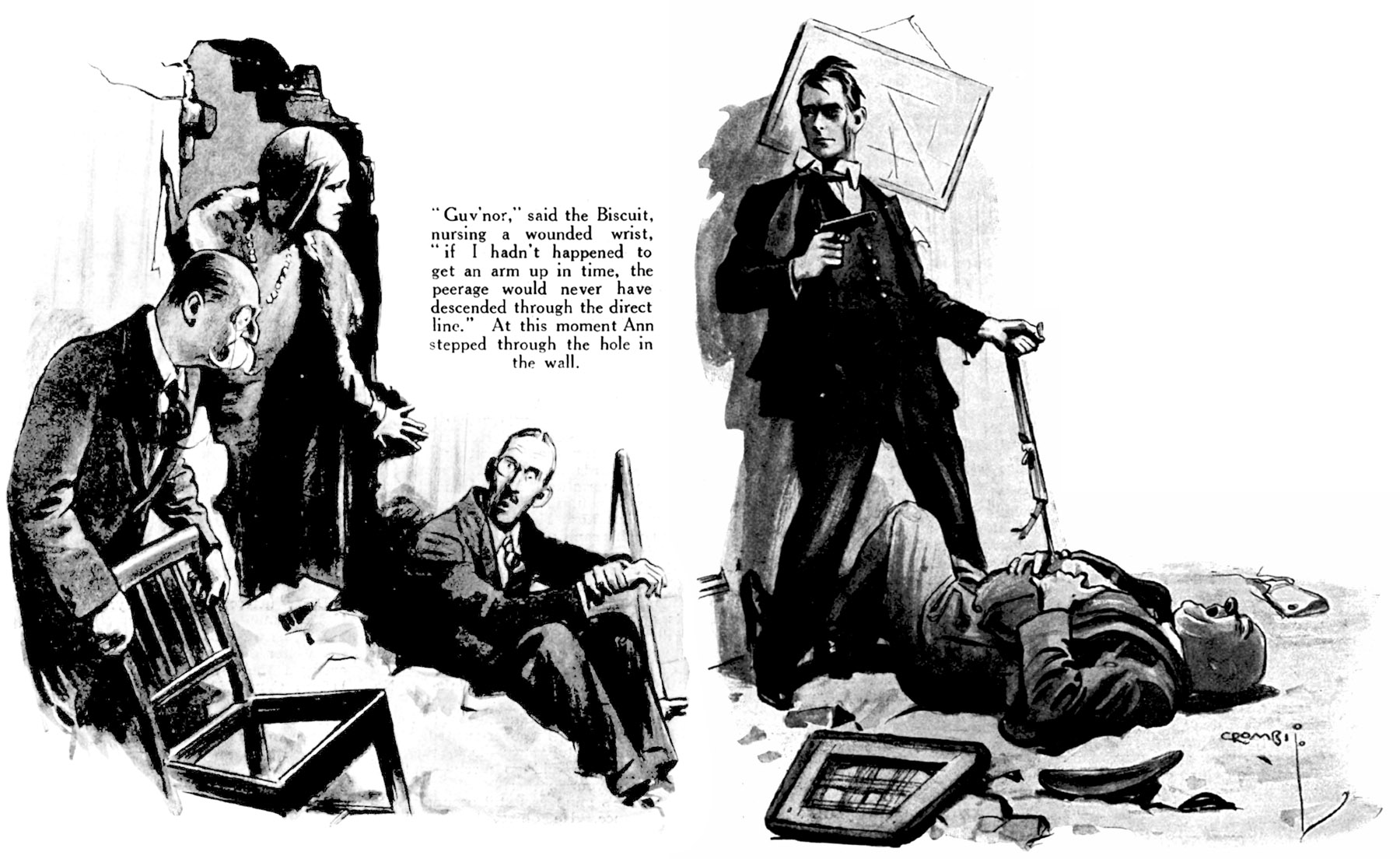

He leaned against the wall, and endeavoured to steady his faithful gat. He did not like the expression on Berry’s face. For the matter of that, he did not like the expression on Lord Hoddesdon’s face. And he was about to say as much, when without any warning there was a loud, splintering crash and quite a lot of the wall fell on top of his head.

“Hell!” cried Mr. Hoke, mystified.

There is always a reason for the most perplexing occurrences. To J. B. Hoke this sudden dissolution of what had appeared to be a solid wall seemed to step straight into the miracle class. And all it was, in reality, was Berry’s next-door neighbour, Lord Biskerton, endeavouring to take a short cut from Peacehaven to The Nook.

We left the Biscuit, it will be recalled, in the act of thinking. A brain of that calibre cannot go on thinking long without some solid result. Suddenly a thought came like a full-blown rose, flushing his brow; and, charging downstairs to the cellar, he came racing up again, armed now with the pickaxe used by suburban householders for breaking coal.

His train of thought may be readily followed. The more he caught the eye of the photograph of his betrothed on the mantelpiece, the more clearly did he perceive that something must be done to dissolve this enforced tête-à-tête between Ann and himself on the premises of Peacehaven. Captain Kelly’s strongly-expressed views had shown him that it was impossible for her to leave by the ordinary route, and so he had adopted the only alternative one. Let him get through into Berry’s sitting-room, he felt, and the thing would at least become a threesome. Good enough, was the Biscuit’s verdict.

He swung his weapon vigorously, and was delighted to find that it met with little resistance. Architects of suburban semi-detached villas do not build party-walls with an eye to this sort of treatment. Encouraged, he redoubled his efforts.

Lord Biskerton, as we have said, was delighted. But it is rarely in this world that we find everybody happy at the same time, and it would be idle to pretend that his exhilaration was shared by Mr. Hoke. What he was going to do about it, beyond uttering a reproving “Hey!” Mr. Hoke did not know: but he knew that he did not like it.

He backed away from the centre of disturbance with a pop-eyed stare of concern; and it was at this moment that Berry, grateful for the opportunity, sprang forward and with a dexterous flick of the foot kicked the pistol out of his hand. He and Mr. Hoke then went into conference on the floor.

Lord Hoddesdon, lowering his aching arms, possessed himself of a stout chair and stood by the rapidly widening hiatus in the wall, awaiting developments. He was feeling warlike, but not surprised. The rigours of life in the suburbs, experienced first by day and now by night, had hardened Lord Hoddesdon’s soul. Just as the traveller to Alaska learns the lesson that there’s never a law of God or man runs north of fifty-three, so had his lordship become aware that every amenity of civilized life must automatically be considered suspended, once you found yourself in the S.E.21 postal district of London.

The gap in the wall widened, and Lord Hoddesdon’s face grew grimmer. Like his great forbear who had done so well at the Battle of Agincourt, he intended, if necessary, to die fighting.

Round and about the imitation Axminster carpet, meanwhile, the catch-as-catch-can struggle between Berry and his visitor was proceeding briskly and with considerable spirit. J. B. Hoke might have been injudicious in the matter of refreshment that day; he might, during his retirement in London, have allowed the enervating conditions of a peaceful life to spoil his figure and impair his wind; but in his hot youth he had been a pretty formidable bar-room scrapper, with an impressive record of victories from the Barbary coast of San Francisco to the Tenderloin district of New York; and much of the ancient skill still lingered. You could tell by the way he kicked Berry on the shin and attempted to get tooth-hold on his left ear that this was no novice who sprawled and wriggled on the floor.

Berry perceived this himself, and he put his whole soul into the fray. And for a space the issue hung doubtful. Then Mr. Hoke made the grave strategic blunder of rising to his feet.

It was not a thing his best friends would have advised. J. B. Hoke was essentially a man who should have stuck to the more free and easy conditions of carpet warfare. Standing up, he offered a too prominent target. Where, on the ground, he had seemed all feet and teeth, he became revealed now as the possessor of a stomach. Berry saw this. He hit Mr. Hoke twice, solidly, in the midriff. And Mr. Hoke, with a defeated gurgle, folded up like an Arab tent and lay prone. And Berry, jumping for the gat which had been the gage of battle, picked it up and stood, panting.

He was attempting to recover some of the breath of which the recent struggle had deprived him, when a crash from behind, followed by a sharp howl, caused him to turn.

His old friend, Lord Biskerton, was sitting on the floor, nursing a wounded wrist, while his old friend’s father, Battling Hoddesdon, stood gazing at his handiwork with surprise and concern.

“Godfrey!”

“Hullo, guv’nor! You here?”

“Godfrey!” cried Lord Hoddesdon. “I’ve hurt you, my boy!”

“Guv’nor,” replied the Biscuit, “you never spoke a truer word. If I hadn’t happened to get an arm up in time, the peerage would never have descended through the direct line.”

At this moment Ann stepped through the hole in the wall.

iv.

“COME right in, Ann,” said the Biscuit cordially. “And thank your stars it wasn’t a case of ladies first. Otherwise you would have caught it on the napper properly. The guv’nor’s just been doing his big tent-pegging act.”

This was only Ann’s third visit to Valley Fields, and she had, in consequence, but a slight acquaintance with the wholesome give-and-take of life in the suburbs of London.

“What has been happening?” she gasped.

Lord Hoddesdon answered the question with the stolidity of an old habitué.

“Lunatic,” he explained. “Dangerous. Mr. Conway overpowered him.”

Ann gazed at Berry emotionally. Her heart was throbbing with all the old love and esteem. One of his eyes was closed, as eyes will close when smartly jabbed by an elbow, and there was blood trickling down his cheek; but she stared at him as at a beautiful picture.

“Why, it’s Hoke,” said the Biscuit, interested. “When did old Hoke go off his onion? He seemed sane enough at lunch.”

Berry laughed unpleasantly.

“He isn’t off his head, Biscuit,” he said. “He knows what he’s doing. Biscuit, you were right. He did do me down over that mine. He’s just been telling me.”

“Yes, he told me, too. Do you realize what this means, Berry?”

“Are you hurt, Berry darling?” said Ann.

Berry stared at her.

“What did you say?”

“I said, ‘Are you hurt?’ ”

“You said ‘darling.’ ”

“Well, of course,” said Ann.

“But——”

“Sweethearts still,” explained the Biscuit. “Recent remarks on her part re never wanting to see you again were made under a misapprehension. The scales have fallen from her eyes.”

“Ann!” said Berry.

“Come here,” said Ann, “and let mother kiss the place and make it well.”

“But—here—dash it!”

It was Lord Hoddesdon who spoke. Affairs of greater urgency had caused him to forget for a while the mission which had brought him down to this house, but he remembered it now, and he gazed with consternation at the horrid picture of Ann—the heiress—old Frisby’s niece—so obviously going out of the family. He looked piteously round at his son, as if seeking support, but the Biscuit had other things on his mind.

“Just a moment,” said the Biscuit. “Are you aware, Berry, that Horned Toad Copper, now quoted at one-and-six, or something like that, is going to shoot up shortly into the hundreds?”

“I am,” said Berry, bitterly. “Hoke told me. That’s why he came here. He sat and held me up with a gun, to prevent me getting to London to buy the stock. Not knowing, poor chump, that I couldn’t have bought the stock if he’d sent a motor to fetch me.”

“Why couldn’t you?”

“I haven’t any money.”

“Yes, you have. You’ve got two thousand quid, and here it is. Cheque requires endorsement.”

Berry regarded the slip of paper, astounded.

“How did you get this?”

“Never mind. I have my methods.”

“It’s signed by Frisby’s lawyer.”

“Never mind who it’s signed by, so long as he’s good for the stuff. Endorse it, and lend me half. A vast fortune stares us in the eye, laddie. Guv’nor,” said the Biscuit, “if you’ve any means of collecting a bit of money to-morrow or the next day, bung it into Horned Toad Copper, and clean up.”

Lord Hoddesdon gulped.

“Frisby gave me a cheque for six hundred pounds only yesterday!”

“He did? One of the most pleasing aspects of this whole binge,” said the Biscuit, “is that that old buccaneer seems to be financing our little venture.” He paused, and a look of despairing gloom came into his face. “Oh, golly!” he moaned.

“What’s the matter?”

The Biscuit’s exuberance had vanished.

“Berry, old man,” he said, “I hate to break it to you, old bird, but in the excitement of the moment I forgot.”

“What?”

“We can’t get out of here. We’re cornered.”

“Why?”

“Hoke’s pal’s waiting outside.”

Berry snorted.

“I’ll soon fix him!”

“But he’s got a gun.”

“So have I.”

“Ah,” said Mr. Hoke, making his first contribution to the conversation, “but it isn’t loaded.”

“What?”

Berry tested the statement, and found it correct.

“Knew all along,” said Mr. Hoke, “there was something I’d forgotten. And that was it.”

“Tie that blighter up, guv’nor,” said the Biscuit, severely, “and bung him in the cellar. And I hope the mice eat him.”

He regarded Mr. Hoke with disapproval. Thanks to Mr. Hoke’s slipshod methods, the garrison of The Nook was helpless.

In the mind of Mr. Hoke, on the other hand, there was nothing but sunshine. All, he realized, was not lost. In fact, nothing was. He himself had been put out of action, but there still remained his excellent friend, Captain Kelly, and Captain Kelly could handle the situation nicely.

“That’s all right about tying me up,” he said. “What good’s that going to do you?”

Berry was making for the door.

“Berry!” cried Ann. “Where are you going?”

Berry stopped.

“Where am I going?” he repeated. “I’m going to knock the stuffing out of that fellow.”

“Berry!” cried Ann.

But Berry had gone.

In the pause that followed, little of note was said, except by Mr. Hoke. Mr. Hoke, in spite of the Biscuit’s well-meant efforts to repress him by kicking him in the ribs, struck an almost lyrical vein on the subject of his partner.

“He’s a gorilla,” said Mr. Hoke. “He never misses.”

He subsided for a moment into a thoughtful silence.

“It seems a pity,” he said. “A nice young fellow like that.”

A scuffling sound outside broke in on his meditations.

“Ah,” said Mr. Hoke, pensively. “This’ll be the body coming back.”

Through the doorway came Berry. He was not alone. Resting on his shoulder was the form of Captain Kelly.

The Captain appeared to have sustained a wound from some blunt instrument.

“Now,” said Berry, “put these two fellows in the cellar, and don’t let them out till we’ve done our bit of business to-morrow.”

“I’ll guard them,” said Lord Hoddesdon.

“How did you manage it, old man?” cried the Biscuit.

Berry was silent for a moment. He seemed to be thinking.

“I have my methods,” he said.

“Berry!” cried Ann.

Berry regarded her fondly. He had only one eye with which to do it, but it was an eye that did the work of two.

“Shall I see you to your car?” he said.

“Yes, do.”

CHAPTER XIV.

“DARLING,” said Berry.

“Yes, darling?” said Ann.

She was seated at the wheel of her car, and he stood, leaning on the side. Mulberry Grove was dark, and scented, and silent.

“Ann,” said Berry, “I’ve something I want to tell you.”

“That you love me?”

“Something else.”

“But you do?”

“I do.”

“In spite of all the beastly things I said to you in the Park?”

“You were quite right.”

“I wasn’t.”

“I did lie to you.”

“Well, never mind.”

“But I do mind. Ann——”

“Yes?”

“I’ve something I want to tell you.”

“Well, go on.”

Berry looked past her at the ornamental water.

“It’s about that fellow.”

“What fellow?”

“Hoke’s friend.”

“What about him?”

“You’ve been saying how brave I was.”

“So you were. It was the bravest thing I ever heard of.”

“You’re looking on me as a sort of hero.”

“Of course I am.”

“Ann,” said Berry, “do you know what happened when I got out? When I got out, I found him lying on the ground with his head in a laurel bush.”

“What?”

“Yes.”

“But——”

“Wait! I’ll tell you. You remember my housekeeper, Mrs. Wisdom?”

“The nice old lady who told me about your bed-socks?”

Berry quivered.

“I’ve never worn bed-socks,” he said, vehemently.

“Well, what about Mrs. Wisdom?”

“I’ll tell you. She is engaged to a local policeman, a man named Finbow.”

“Well?”

“She and Finbow had been to the pictures in Brixton.”

“Well?”

“She came back,” proceeded Berry, doggedly, “and she found a strange man lurking in our front garden.”

“Well?”

“She thought he was a burglar.”

“Well?”

“So,” said Berry, “she hit him on the head with her umbrella and knocked him out, and all I had to do was carry him in. Now you know.”

There was a silence. Then Ann leaned quickly over the side of the car and kissed the top of his head.

“And you thought I would mind?”

“I thought you would wish you hadn’t made quite such a fuss over my reckless courage.”

“But still you told me?”

“Yes.”

Ann kissed the top of his head again.

“Quite right,” she said. “Mother always wants her little man to tell her the truth.”

the end

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums