The Strand Magazine, January 1924

THE Theatre Royal, Llunindnno, is in the middle of the principal thoroughfare of that repellent town, and immediately opposite its grubby main entrance there is a lamp-post. Under this lamp-post, as I approached, a man was standing. He was a large man, and his air was that of one who has recently passed through some trying experience. There was dust on his person, and he had lost his hat. At the sound of my footsteps he turned, and the rays of the lamp revealed the familiar features of my old friend Stanley Featherstonehaugh Ukridge.

“Great Scott!” I ejaculated. “What are you doing here?”

There was no possibility of hallucination. It was the man himself in the flesh. And what Ukridge, a free agent, could be doing in Llunindnno was more than I could imagine. Situated, as its name implies, in Wales, it is a dark, dingy, dishevelled spot, inhabited by tough and sinister men with suspicious eyes and three-day beards; and to me, after a mere forty minutes’ sojourn in the place, it was incredible that anyone should be there except on compulsion.

Ukridge gaped at me incredulously.

“Corky, old horse!” he said, “this is, upon my Sam, without exception the most amazing event in the world’s history. The last bloke I expected to see.”

“Same here. Is anything the matter?” I asked, eyeing his bedraggled appearance.

“Matter? I should say something was the matter!” snorted Ukridge, astonishment giving way to righteous indignation. “They chucked me out!”

“Chucked you out? Who? Where from?”

“This infernal theatre, laddie. After taking my good money, dash it! At least, I got in on my face, but that has nothing to do with the principle of the thing. Corky, my boy, don’t you ever go about this world seeking for justice, because there’s no such thing under the broad vault of heaven. I had just gone out for a breather after the first act, and when I came back I found some fiend in human shape had pinched my seat. And just because I tried to lift the fellow out by the ears, a dozen hired assassins swooped down and shot me out. Me, I’ll trouble you! The injured party! Upon my Sam,” he said, heatedly, with a longing look at the closed door, “I’ve a dashed good mind to——”

“I shouldn’t,” I said, soothingly. “After all, what does it matter? It’s just one of those things that are bound to happen from time to time. The man of affairs passes them off with a light laugh.”

“Yes, but——”

“Come and have a drink.”

The suggestion made him waver. The light of battle died down in his eyes. He stood for a moment in thought.

“You wouldn’t bung a brick through the window?” he queried, doubtfully.

“No, no!”

“Perhaps you’re right.”

He linked his arm in mine and we crossed the road to where the lights of a public-house shone like heartening beacons. The crisis was over.

“Corky,” said Ukridge, warily laying down his mug of beer on the counter a few moments later, lest emotion should cause him to spill any of its precious contents, “I can’t get over, I simply cannot get over the astounding fact of your being in this blighted town.”

I explained my position. My presence in Llunindnno was due to the fact that the paper which occasionally made use of my services as a special writer had sent me to compose a fuller and more scholarly report than its local correspondent seemed capable of concocting of the activities of one Evan Jones, the latest of those revivalists who periodically convulse the emotions of the Welsh mining population. His last and biggest meeting was to take place next morning at eleven o’clock.

“But what are you doing here?” I asked.

“What am I doing here?” said Ukridge. “Who, me? Why, where else would you expect me to be? Haven’t you heard?”

“Heard what?”

“Haven’t you seen the posters?”

“What posters? I only arrived an hour ago.”

“My dear old horse! Then naturally you aren’t abreast of local affairs.” He drained his mug, breathed contentedly, and led me out into the street. “Look!”

He was pointing at a poster, boldly lettered in red and black, which decorated the side-wall of the Bon Ton Millinery Emporium. The street-lighting system of Llunindnno is defective, but I was able to read what it said:—

ODDFELLOWS’ HALL.

Special Ten-Round Contest.

LLOYD THOMAS

(Llunindnno)

vs.

BATTLING BILLSON

(Bermondsey).

“Comes off to-morrow night,” said Ukridge. “And I don’t mind telling you, laddie, that I expect to make a colossal fortune.”

“Are you still managing the Battler?” I said, surprised at this dogged perseverance. “I should have thought that after your last two experiences you would have had about enough of it.”

“Oh, he means business this time! I’ve been talking to him like a father.”

“How much does he get?”

“Twenty quid.”

“Twenty quid? Well, where does the colossal fortune come in? Your share will only be a tenner.”

“No, my boy. You haven’t got on to my devilish shrewdness. I’m not in on the purse at all this time. I’m the management.”

“The management?”

“Well, part of it. You remember Isaac O’Brien, the bookie I was partner with till that chump Looney Coote smashed the business? Izzy Previn is his real name. We've gone shares in this thing. Izzy came down a week ago, hired the hall, and looked after the advertising and so on; and I arrived with good old Billson this afternoon. We’re giving him twenty quid, and the other fellow’s getting another twenty; and all the rest of the cash Izzy and I split on a fifty-fifty basis. Affluence, laddie! That’s what it means. Affluence beyond the dreams of a Monte Cristo. Owing to this Jones fellow the place is crowded, and every sportsman for miles around will be there to-morrow at five bob a head, cheaper seats two-and-six, and standing-room one shilling. Add lemonade and fried fish privileges, and you have a proposition almost without parallel in the annals of commerce. I couldn’t be more on velvet if they gave me a sack and a shovel and let me loose in the Mint.”

I congratulated him in suitable terms.

“How is the Battler?” I asked.

“Trained to an ounce. Come and see him to-morrow morning.”

“I can’t come in the morning. I’ve got to go to this Jones meeting.”

“Oh, yes. Well, make it early in the afternoon, then. Don’t come later than three, because he will be resting. We’re at Number Seven, Caerleon Street. Ask for the Cap and Feathers public-house, and turn sharp to the left.”

I WAS in a curiously uplifted mood on the following afternoon as I set out to pay my respects to Mr. Billson. This was the first time I had had occasion to attend one of these revival meetings, and the effect it had had on me was to make me feel as if I had been imbibing large quantities of champagne to the accompaniment of a very loud orchestra. Even before the revivalist rose to speak, the proceedings had had an effervescent quality singularly unsettling to the sober mind, for the vast gathering had begun to sing hymns directly they took their seats; and while the opinion I had formed of the inhabitants of Llunindnno was not high, there was no denying their vocal powers. There is something about a Welsh voice when raised in song that no other voice seems to possess—a creepy, heart-searching quality that gets right into a man’s inner consciousness and stirs it up with a pole. And on top of this had come Evan Jones’s address.

It did not take me long to understand why this man had gone through the countryside like a flame. He had magnetism, intense earnestness, and the voice of a prophet crying in the wilderness. His fiery eyes seemed to single out each individual in the hall, and every time he paused sighings and wailings went up like the smoke of a furnace. And then, after speaking for what I discovered with amazement on consulting my watch was considerably over an hour, he stopped. And I blinked like an aroused somnambulist, shook myself to make sure I was still there, and came away. And now, as I walked in search of the Cap and Feathers, I was, as I say, oddly exhilarated: and I was strolling along in a sort of trance when a sudden uproar jerked me from my thoughts. I looked about me, and saw the sign of the Cap and Feathers suspended over a building across the street.

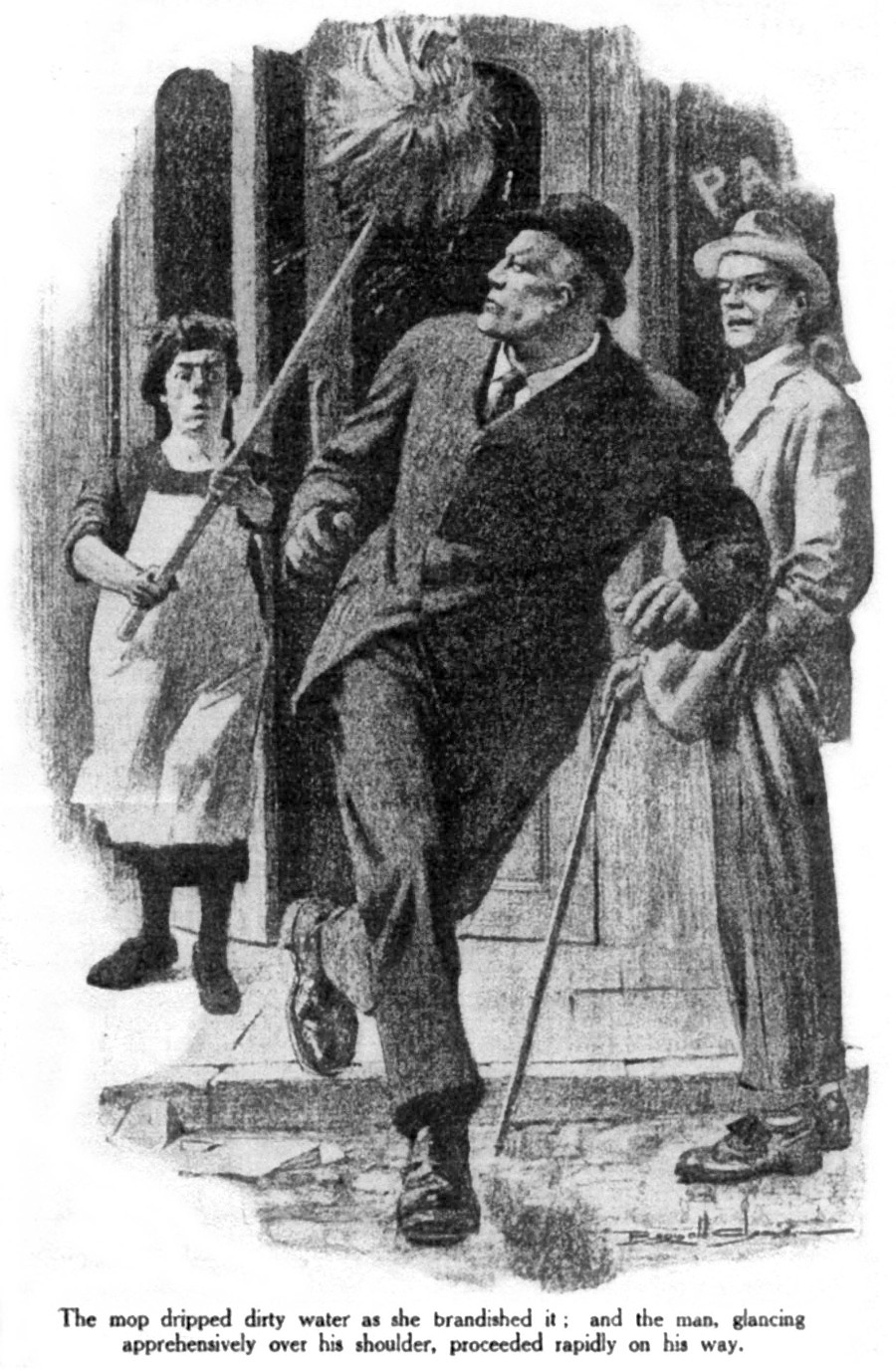

It was a dubious-looking hostelry in a dubious neighbourhood: and the sounds proceeding from its interior were not reassuring to a peace-loving pedestrian. There was a good deal of shouting going on and much smashing of glass; and, as I stood there, the door flew open and a familiar figure emerged rather hastily. A moment later there appeared in the doorway a woman.

She was a small woman, but she carried the largest and most intimidating mop I had ever seen. It dripped dirty water as she brandished it; and the man, glancing apprehensively over his shoulder, proceeded rapidly on his way.

“Hullo, Mr. Billson!” I said, as he shot by me.

IT was not, perhaps, the best-chosen moment for endeavouring to engage him in light conversation. He showed no disposition whatever to linger. He vanished round the corner, and the woman, with a few winged words, gave her mop a victorious flourish and re-entered the public-house. I walked on, and a little later a huge figure stepped cautiously out of an alleyway and fell into step at my side.

“Didn’t recognize you, mister,” said Mr. Billson, apologetically.

“You seemed in rather a hurry,” I agreed.

“R!” said Mr. Billson, and a thoughtful silence descended upon him for a space.

“Who,” I asked, tactlessly, perhaps, “was your lady friend?”

Mr. Billson looked a trifle sheepish. Unnecessarily, in my opinion. Even heroes may legitimately quail before a mop wielded by an angry woman.

“She come out of a back room,” he said, with embarrassment. “Started makin’ a fuss when she saw what I’d done. So I come away. You can’t dot a woman,” argued Mr. Billson, chivalrously.

“Certainly not,” I agreed. “But what was the trouble?”

“I been doin’ good,” said Mr. Billson, virtuously.

“Doing good?”

“Spillin’ their beers.”

“Whose beers?”

“All of their beers. I went in and there was a lot of sinful fellers drinkin’ beers. So I spilled ’em. All of ’em. Walked round and spilled all of them beers, one after the other. Not ’arf surprised them pore sinners wasn’t,” said Mr. Billson, with what sounded to me not unlike a worldly chuckle.

“I can readily imagine it.”

“Huh?”

“I say I bet they were.”

“R!” said Mr. Billson. He frowned. “Beer,” he proceeded, with cold austerity, “ain’t right. Sinful, that’s what beer is. It stingeth like a serpent and biteth like a ruddy adder.”

My mouth watered a little. Beer like that was what I had been scouring the country for for years. I thought it imprudent, however, to say so. For some reason which I could not fathom, my companion, once as fond of his half-pint as the next man, seemed to have conceived a puritanical hostility to the beverage. I decided to change the subject.

“I’m looking forward to seeing you fight to-night,” I said.

He eyed me woodenly.

“Me?”

“Yes. At the Oddfellows’ Hall, you know.”

He shook his head.

“I ain’t fighting at no Oddfellows’ Hall,” he replied. “Not at no Oddfellows’ Hall nor nowhere else I’m not fighting, not tonight nor no night.” He pondered stolidly, and then, as if coming to the conclusion that his last sentence could be improved by the addition of a negative, added “No!”

And having said this, he suddenly stopped and stiffened like a pointing dog; and, looking up to see what interesting object by the wayside had attracted his notice, I perceived that we were standing beneath another public-house sign, that of the Blue Boar. Its windows were hospitably open, and through them came a musical clinking of glasses. Mr. Billson licked his lips with a quiet relish.

“ ’Scuse me, mister,” he said, and left me abruptly.

MY one thought now was to reach Ukridge as quickly as possible, in order to acquaint him with these sinister developments. For I was startled. More, I was alarmed and uneasy. In one of the star performers at a special ten-round contest, scheduled to take place that evening, Mr. Billson’s attitude seemed to me peculiar, not to say disquieting. So, even though a sudden crash and uproar from the interior of the Blue Boar called invitingly to me to linger, I hurried on, and neither stopped, looked, nor listened until I stood on the steps of Number Seven, Caerleon Street. And eventually, after my prolonged ringing and knocking had finally induced a female of advanced years to come up and open the door, I found Ukridge lying on a horse-hair sofa in the far corner of the sitting-room.

I unloaded my grave news. It was wasting time to try to break it gently.

“I’ve just seen Billson,” I said, “and he seems to be in rather a strange mood. In fact, I’m sorry to say, old man, he rather gave me the impression——”

“That he wasn’t going to fight to-night?” said Ukridge, with a strange calm. “Quite correct. He isn’t. He’s just been in here to tell me so. What I like about the man is his consideration for all concerned. He doesn’t want to upset anybody’s arrangements.”

“But what’s the trouble? Is he kicking about only getting twenty pounds?”

“No. He thinks fighting’s sinful!”

“What?”

“Nothing more nor less, Corky, my boy. Like chumps, we took our eyes off him for half a second this morning, and he sneaked off to that revival meeting. Went out shortly after a light and wholesome breakfast for what he called a bit of a mooch round, and came in half an hour ago a changed man. Full of loving-kindness, curse him. Nasty shifty gleam in his eye. Told us he thought fighting sinful and it was all off, and then buzzed out to spread the Word.”

I was shaken to the core. Wilberforce Billson, the peerless but temperamental Battler, had never been an ideal pugilist to manage, but hitherto he had drawn the line at anything like this. Other little problems which he might have brought up for his manager to solve might have been overcome by patience and tact; but not this one. The psychology of Mr. Billson was as an open book to me. He possessed one of those single-track minds, capable of accommodating but one idea at a time, and he had the tenacity of the simple soul. Argument would leave him unshaken. On that bone-like head Reason would beat in vain. And, these things being so, I was at a loss to account for Ukridge’s extraordinary calm. His fortitude in the hour of ruin amazed me.

His next remark, however, offered an explanation.

“We’re putting on a substitute,” he said.

I was relieved.

“Oh, you’ve got a substitute? That’s a bit of luck. Where did you find him?”

“As a matter of fact, laddie, I’ve decided to go on myself.”

“What! You!”

“Only way out, my boy. No other solution.”

I stared at the man. Years of the closest acquaintance with S. F. Ukridge had rendered me almost surprise-proof at anything he might do, but this was too much.

“Do you mean to tell me that you seriously intend to go out there to-night and appear in the ring?” I cried.

“Perfectly straightforward business-like proposition, old man,” said Ukridge, stoutly. “I’m in excellent shape. I sparred with Billson every day while he was training.”

“Yes, but——”

“The fact is, laddie, you don’t realize my potentialities. Recently, it’s true, I’ve allowed myself to become slack and what you might call enervated, but, damme, when I was on that trip in that tramp-steamer, scarcely a week used to go by without my having a good earnest scrap with somebody. Nothing barred,” said Ukridge, musing lovingly on the care-free past, “except biting and bottles.”

“Yes, but, hang it—a professional pugilist!”

“Well, to be absolutely accurate, laddie,” said Ukridge, suddenly dropping the heroic manner and becoming confidential, “the thing's going to be fixed. Izzy Previn has seen the bloke Thomas’s manager, and has arranged a gentleman’s agreement. The manager, a Class A bloodsucker, insists on us giving his man another twenty pounds after the fight, but that can’t be helped. In return, the Thomas bloke consents to play light for three rounds, at the end of which period, laddie, he will tap me on the side of the head and I shall go down and out, a popular loser. What’s more, I’m allowed to hit him hard—once—just so long as it isn’t on the nose. So you see, a little tact, a little diplomacy, and the whole thing fixed up as satisfactorily as anyone could wish.”

“But suppose the audience demands its money back when they find they’re going to see a substitute?”

“My dear old horse,” protested Ukridge, “surely you don’t imagine that a man with a business head like mine overlooked that? Naturally, I’m going to fight as Battling Billson. Nobody knows him in this town. I’m a good big chap, just as much a heavyweight as he is. No, laddie, pick how you will you can’t pick a flaw in this.”

“Why mayn’t you hit him on the nose?”

“I don’t know. People have these strange whims. And now, Corky, my boy, I think you had better leave me. I ought to relax.”

THE Oddfellows’ Hall was certainly filling up nicely when I arrived that night. Indeed, it seemed as though Llunindnno’s devotees of sport would cram it to the roof. I took my place in the line before the pay-window, and, having completed the business end of the transaction, went in and inquired my way to the dressing-rooms. And presently, after wandering through divers passages, I came upon Ukridge, clad for the ring and swathed in his familiar yellow mackintosh.

“You’re going to have a wonderful house,” I said. “The populace is rolling up in shoals.”

He received the information with a strange lack of enthusiasm. I looked at him in concern, and was disquieted by his forlorn appearance. That face, which had beamed so triumphantly at our last meeting, was pale and set. Those eyes, which normally shone with the flame of an unquenchable optimism, seemed dull and careworn. And even as I looked at him he seemed to rouse himself from a stupor and, reaching out for his shirt, which hung on a near-by peg, proceeded to pull it over his head.

“What’s the matter?” I asked.

His head popped out of the shirt, and he eyed me warily.

“I’m off,” he announced, briefly.

“Off? How do you mean, off?” I tried to soothe what I took to be an eleventh-hour attack of stage-fright. “You’ll be all right.”

Ukridge laughed hollowly.

“Once the gong goes, you’ll forget the crowd.”

“It isn’t the crowd,” said Ukridge, in a pale voice, climbing into his trousers. “Corky, old man,” he went on, earnestly, “if ever you feel your angry passions rising to the point where you want to swat a stranger in a public place, restrain yourself. There’s nothing in it. This bloke Thomas was in here a moment ago with his manager to settle the final details. He’s the fellow I had the trouble with at the theatre last night!”

“The man you pulled out of the seat by his ears?” I gasped.

Ukridge nodded.

“Recognized me at once, confound him, and it was all his manager, a thoroughly decent cove whom I liked, could do to prevent him getting at me there and then.”

“Good Lord!” I said, aghast at this grim development, yet thinking how thoroughly characteristic it was of Ukridge, when he had a whole townful of people to quarrel with, to pick the one professional pugilist.

At this moment, when Ukridge was lacing his left shoe, the door opened and a man came in.

The new-comer was stout, dark, and beady-eyed, and from his manner of easy comradeship and the fact that when he spoke he supplemented words with the language of the waving palm, I deduced that this must be Mr. Izzy Previn, recently trading as Isaac O’Brien. He was cheeriness itself.

“Vell,” he said, with ill-timed exuberance, “how’th the boy?”

The boy cast a sour look at him.

“The house,” proceeded Mr. Previn, with an almost lyrical enthusiasm, “is absolutely full. Crammed, jammed, and packed. They’re hanging from the roof by their eyelids. It’th goin’ to be a knock-out.”

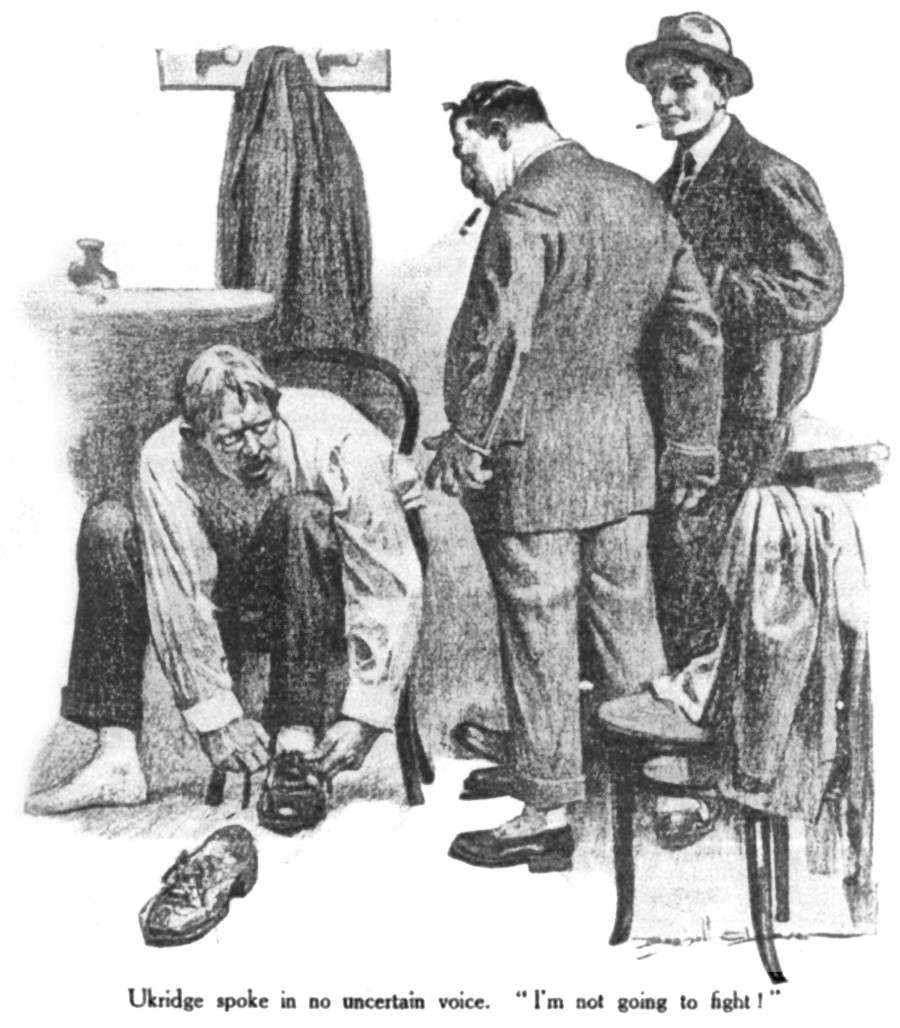

The expression, considering the circumstances, could hardly have been less happily chosen. Ukridge winced painfully, then spoke in no uncertain voice.

“I’m not going to fight!”

Mr. Previn’s exuberance fell from him like a garment. His cigar dropped from his mouth, and his beady eyes glittered with sudden consternation.

“What do you mean?”

“Rather an unfortunate thing has happened,” I explained. “It seems that this man Thomas is a fellow Ukridge had trouble with at the theatre last night.”

“What do you mean, Ukridge?” broke in Mr. Previn. “This is Battling Billson.”

“I’ve told Corky all about it,” said Ukridge over his shoulder as he laced his right shoe. “Old pal of mine.”

“Oh!” said Mr. Previn, relieved. “Of course, if Mr. Corky is a friend of yours and quite understands that all this is quite private among ourselves and don’t want talking about outside, all right. But what were you thayin’? I can’t make head or tail of it. How do you mean, you’re not goin’ to fight? Of course you’re goin’ to fight.”

“Thomas was in here just now,” I said. “Ukridge and he had a row at the theatre last night, and naturally Ukridge is afraid he will go back on the agreement.”

“Nonthense,” said Mr. Previn, and his manner was that of one soothing a refractory child. “He won’t go back on the agreement. He promised he’d play light and he will play light. Gave me his word as a gentleman.”

“He isn’t a gentleman,” Ukridge pointed out, moodily.

“But lithen!”

“I’m going to get out of here as quick as I dashed well can!”

“Conthider!” pleaded Mr. Previn, clawing great chunks out of the air.

Ukridge began to button his collar.

“Reflect!” moaned Mr. Previn. “There’s that lovely audience all sitting out there, jammed like thardines, waiting for the thing to start. Do you expect me to go and tell ’em there ain’t goin’ to be no fight? I’m thurprised at you,” said Mr. Previn, trying an appeal to his pride. “Where’s your manly spirit? A big, husky feller like you, that’s done all sorts of scrappin’ in your time——”

“Not,” Ukridge pointed out coldly, “with any damned professional pugilists who’ve got a grievance against me.”

“He won’t hurt you.”

“He won’t get the chance.”

“You’ll be as safe and cosy in that ring with him as if you was playing ball with your little thister.”

Ukridge said he hadn’t got a little sister.

“But think!” implored Mr. Previn, flapping like a seal. “Think of the money! Do you realize we’ll have to return it all, every penny of it?”

A spasm of pain passed over Ukridge’s face, but he continued buttoning his collar.

“And not only that,” said Mr. Previn, “but, if you ask me, they’ll be so mad when they hear there ain’t goin’ to be no fight, they’ll lynch me.”

Ukridge seemed to regard this possibility with calm.

“And you, too,” added Mr. Previn.

Ukridge started. It was a plausible theory, and one that had not occurred to him before. He paused irresolutely. And at this moment a man came hurrying in.

“What’s the matter?” he demanded, fussily. “Thomas has been in the ring for five minutes. Isn’t your man ready?”

“In one half tick,” said Mr. Previn. He turned meaningly to Ukridge. “That’s right, ain’t it? You’ll be ready in half a tick?”

Ukridge nodded wanly. In silence he shed shirt, trousers, shoes, and collar, parting from them as if they were old friends whom he never expected to see again. One wistful glance he cast at his mackintosh, lying forlornly across a chair; and then, with more than a suggestion of a funeral procession, we started down the corridor that led to the main hall. The hum of many voices came to us; there was a sudden blaze of light, and we were there.

I MUST say for the sport-loving citizens of Llunindnno that they appeared to be fair-minded men. Stranger in their midst though he was, they gave Ukridge an excellent reception as he climbed into the ring; and for a moment, such is the tonic effect of applause on a large scale, his depression seemed to lift. A faint, gratified smile played about his drawn mouth, and I think it would have developed into a bashful grin, had he not at this instant caught sight of the redoubtable Mr. Thomas towering massively across the way. I saw him blink, as one who, thinking absently of this and that, walks suddenly into a lamp-post; and his look of unhappiness returned.

My heart bled for him. If the offer of my little savings in the bank could have transported him there and then to the safety of his London lodgings, I would have made it unreservedly. Mr. Previn had disappeared, leaving me standing at the ring-side, and as nobody seemed to object I remained there, thus getting an excellent view of the mass of bone and sinew that made up Lloyd Thomas. And there was certainly plenty of him to see.

Mr. Thomas was, I should imagine, one of those men who do not look their most formidable in mufti—for otherwise I could not conceive how even the fact that he had stolen his seat could have led Ukridge to lay the hand of violence upon him. In the exiguous costume of the ring he looked a person from whom the sensible man would suffer almost any affront with meekness. He was about six feet in height, and where ever a man could bulge with muscle he bulged. For a moment my anxiety for Ukridge was tinged with a wistful regret that I should never see this sinewy citizen in action with Mr. Billson. It would, I mused, have been a battle worth coming even to Llunindnno to see.

The referee, meanwhile, had been introducing the principals in the curt, impressive fashion of referees. He now retired, and with a strange foreboding note a gong sounded on the farther side of the ring. The seconds scuttled under the ropes. The man Thomas, struggling—it seemed to me—with powerful emotions, came ponderously out of his corner.

In these reminiscences of a vivid and varied career, it is as a profound thinker that I have for the most part had occasion to portray Stanley Featherstonehaugh Ukridge. I was now to be reminded that he also had it in him to be a doer. Even as Mr. Thomas shuffled towards him, his left fist shot out and thudded against the other’s ribs. In short, in a delicate and difficult situation, Ukridge was comporting himself with an adequacy that surprised me. However great might have been his reluctance to embark on this contest, once in he was doing well.

And then, half-way through the first round, the truth dawned upon me. Injured though Mr. Thomas had been, the gentleman’s agreement still held. The word of a Thomas was as good as his bond. Poignant though his dislike of Ukridge might be, nevertheless, having pledged himself to mildness and self-restraint for the first three rounds, he intended to abide by the contract. Probably, in the interval between his visit to Ukridge’s dressing-room and his appearance in the ring, his manager had been talking earnestly to him. At any rate, whether it was managerial authority or his own sheer nobility of character that influenced him, the fact remains that he treated Ukridge with a quite remarkable forbearance, and the latter reached his corner at the end of round one practically intact.

And it was this that undid him. No sooner had the gong sounded for round two than out he pranced from his corner, thoroughly above himself. He bounded at Mr. Thomas like a Dervish.

I could read his thoughts as if he had spoken them. Nothing could be clearer than that he had altogether failed to grasp the true position of affairs. Instead of recognizing his adversary’s forbearance for what it was and being decently grateful for it, he was filled with a sinful pride. Here, he told himself, was a man who had a solid grievance against him—and, dash it, the fellow couldn’t hurt him a bit. What the whole thing boiled down to, he felt, was that he, Ukridge, was better than he had suspected, a man to be reckoned with, and one who could show a distinguished gathering of patrons of sport something worth looking at. The consequence was that, where any sensible person would have grasped the situation at once and endeavoured to show his appreciation by toying with Mr. Thomas in gingerly fashion, whispering soothing compliments into his ear during the clinches, and generally trying to lay the foundations of a beautiful friendship against the moment when the gentleman’s agreement should lapse, Ukridge committed the one unforgivable act. There was a brief moment of fiddling and feinting in the centre of the ring, then a sharp smacking sound, a startled yelp, and Mr. Thomas, with gradually reddening eye, leaning against the ropes and muttering to himself in Welsh.

Ukridge had hit him on the nose!

ONCE more I must pay a tribute to the fair-mindedness of the sportsmen of Llunindnno. The stricken man was one of them—possibly Llunindnno’s favourite son—yet nothing could have exceeded the heartiness with which they greeted the visitor’s achievement. A shout went up as if Ukridge had done each individual present a personal favour. It continued as he advanced buoyantly upon his antagonist, and—to show how entirely Llunindnno audiences render themselves impartial and free from any personal bias—it became redoubled as Mr. Thomas, swinging a fist like a ham, knocked Ukridge flat on his back. Whatever happened, so long as it was sufficiently violent, seemed to be all right with that broad-minded audience.

Ukridge heaved himself laboriously to one knee. His sensibilities had been ruffled by this unexpected blow, about fifteen times as hard as the others he had received since the beginning of the affray, but he was a man of mettle and determination. However humbly he might quail before a threatening landlady, or however nimbly he might glide down a side-street at the sight of an approaching creditor, there was nothing wrong with his fighting heart when it came to a straight issue between man and man, untinged by the financial element. He struggled painfully to his feet, while Mr. Thomas, now definitely abandoning the gentleman’s agreement, hovered about him with ready fists, only restrained by the fact that one of Ukridge’s gloves still touched the floor.

It was at this tensest of moments that a voice spoke in my ear.

“ ’Alf a mo’, mister!”

A hand pushed me gently aside. Something large obscured the lights. And Wilberforce Billson, squeezing under the ropes, clambered into the ring.

FOR the purposes of the historian it was a good thing that for the first few moments after this astounding occurrence a dazed silence held the audience in its grip. Otherwise, it might have been difficult to probe motives and explain underlying causes. I think the spectators were either too surprised to shout, or else they entertained for a few brief seconds the idea that Mr. Billson was the forerunner of a posse of plain-clothes police about to raid the place. At any rate, for a space they were silent, and he was enabled to say his say.

“Fightin’,” bellowed Mr. Billson, “ain’t right!”

There was an uneasy rustle in the audience. The voice of the referee came thinly, saying, “Here! Hi!”

“Sinful,” explained Mr. Billson, in a voice like a fog-horn.

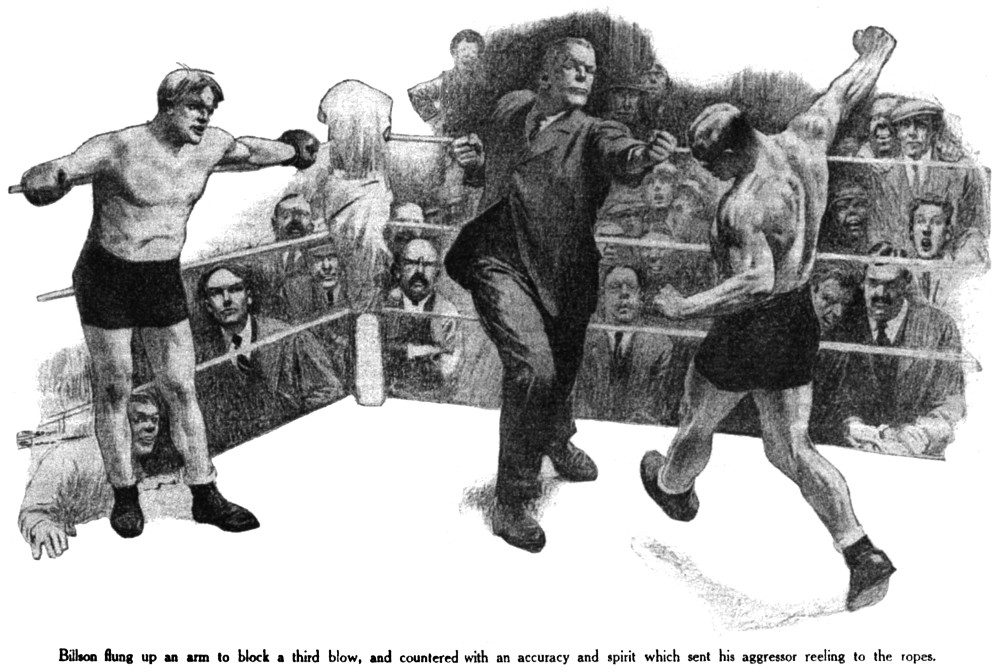

His oration was interrupted by Mr. Thomas, who was endeavouring to get round him and attack Ukridge. The Battler pushed him gently back.

“Gents,” he roared, “I, too, have been a man of voylence! I ’ave struck men in anger. R, yes! But I ’ave seen the light. Oh, my brothers——”

The rest of his remarks were lost. With a startling suddenness the frozen silence melted. In every part of the hall indignant seatholders were rising to state their views.

But it is doubtful whether, even if he had been granted a continuance of their attention, Mr. Billson would have spoken to much greater length; for at this moment Lloyd Thomas, who had been gnawing at the strings of his gloves with the air of a man who is able to stand just so much and whose limit has been exceeded, now suddenly shed these obstacles to the freer expression of self, and, advancing barehanded, smote Mr. Billson violently on the jaw.

Mr. Billson turned. He was pained, one could see that, but more spiritually than physically. For a moment he seemed uncertain how to proceed. Then he turned the other cheek.

The fermenting Mr. Thomas smote that, too.

There was no vacillation or uncertainty now about Wilberforce Billson. He plainly considered that he had done all that could reasonably be expected of any pacifist. A man has only two cheeks. He flung up a mast-like arm to block a third blow, countered with an accuracy and spirit which sent his aggressor reeling to the ropes; and then, swiftly removing his coat, went into action with the unregenerate zeal that had made him the petted hero of a hundred waterfronts. And I, tenderly scooping Ukridge up as he dropped from the ring, hurried him away along the corridor to his dressing-room. I would have given much to remain and witness a mix-up which, if the police did not interfere, promised to be the battle of the ages, but the claims of friendship are paramount.

Ten minutes later, however, when Ukridge, washed, clothed, and restored as near to the normal as a man may be who has received the full weight of a Lloyd Thomas on a vital spot, was reaching for his mackintosh, there filtered through the intervening doors and passageways a sudden roar so compelling that my sporting spirit declined to ignore it.

“Back in a minute, old man,” I said.

And, urged by that ever-swelling roar, I cantered back to the hall.

IN the interval during which I had been ministering to my stricken friend a certain decorum seemed to have been restored to the proceedings. The conflict had lost its first riotous abandon. Upholders of the decencies of debate had induced Mr. Thomas to resume his gloves, and a pair had also been thrust upon the Battler. Moreover, it was apparent that the etiquette of the tourney now governed the conflict, for rounds had been introduced, and one had just finished as I came in view of the ring. Mr. Billson was leaning back in a chair in one corner undergoing treatment by his seconds, and in the opposite corner loomed Mr. Thomas; and one sight of the two men was enough to tell me what had caused that sudden tremendous outburst of enthusiasm among the patriots of Llunindnno. In the last stages of the round which had just concluded the native son must have forged ahead in no uncertain manner. Perhaps some chance blow had found its way through the Battler’s guard, laying him open and defenceless to the final attack. For his attitude, as he sagged in his corner, was that of one whose moments are numbered. His eyes were closed, his mouth hung open, and exhaustion was writ large upon him. Mr. Thomas, on the contrary, leaned forward with hands on knees, wearing an impatient look, as if this formality of a rest between rounds irked his imperious spirit.

The gong sounded and he sprang from his seat.

“Laddie!” breathed an anguished voice, and a hand clutched my arm.

I was dimly aware of Ukridge standing beside me. I shook him off. This was no moment for conversation. My whole attention was concentrated on what was happening in the ring.

“I say, laddie!”

Matters in there had reached that tense stage when audiences lose their self-control—when strong men stand on seats and weak men cry “Siddown!” The air was full of that electrical thrill that precedes the knock-out.

And the next moment it came. But it was not Lloyd Thomas who delivered it. From some mysterious reservoir of vitality Wilberforce Billson, the pride of Bermondsey, who an instant before had been reeling under his antagonist’s blows like a stricken hulk before a hurricane, produced that one last punch that wins battles. Up it came, whizzing straight to its mark, a stupendous, miraculous upper-cut which caught Mr. Thomas on the angle of the jaw just as he lurched forward to complete his task. It was the last word. Anything milder Llunindnno’s favourite son might have borne with fortitude, for his was a teak-like frame impervious to most things short of dynamite; but this was final. It left no avenue for argument or evasion. Lloyd Thomas spun round once in a complete circle, dropped his hands, and sank slowly to the ground.

There was one wild shout from the audience, and then a solemn hush fell. And in this hush Ukridge’s voice spoke once more in my ear.

“I say, laddie, that blighter Previn has bolted with every penny of the receipts!”

THE little sitting-room of Number Seven, Caerleon Street, was very quiet and gave the impression of being dark. This was because there is so much of Ukridge and he takes Fate’s blows so hardly that, when anything goes wrong, his gloom seems to fill a room like a fog. For some minutes after our return from the Oddfellows’ Hall a gruesome silence had prevailed. Ukridge had exhausted his vocabulary on the subject of Mr. Previn; and as for me, the disaster seemed so tremendous as to render words of sympathy a mere mockery.

“And there’s another thing I’ve just remembered,” said Ukridge, hollowly, stirring on his sofa.

“What’s that?” I inquired, in a bedside voice.

“The bloke Thomas. He was to have got another twenty pounds.”

“He’ll hardly claim it, surely?”

“He’ll claim it all right,” said Ukridge, moodily. “Except, by Jove,” he went on, a sudden note of optimism in his voice, “that he doesn’t know where I am. I was forgetting that. Lucky we legged it away from the hall before he could grab me.”

“You don’t think that Previn, when he was making the arrangements with Thomas’s manager, may have mentioned where you were staying?”

“Not likely. Why should he? What reason would he have?”

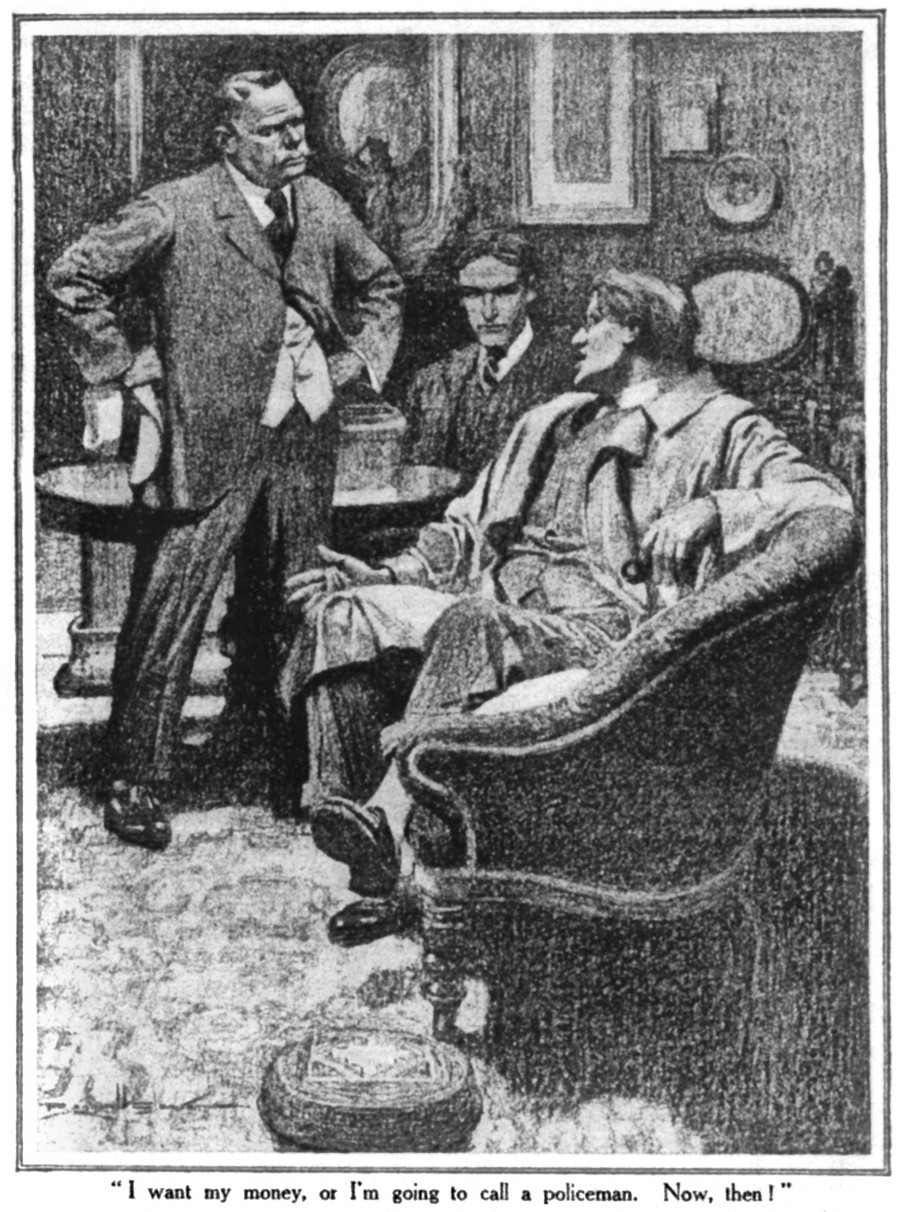

“Gentleman to see you, sir,” crooned the aged female at the door.

The gentleman walked in. It was the man who had come to the dressing-room to announce that Thomas was in the ring; and though on that occasion we had not been formally introduced I did not need Ukridge’s faint groan to tell me who he was.

“Mr. Previn?” he said. He was a brisk man, direct in manner and speech.

“He’s not here,” said Ukridge.

“You’ll do. You’re his partner. I’ve come for that twenty pounds.”

There was a painful silence.

“It’s gone,” said Ukridge.

“What’s gone?”

“The money, dash it. And Previn, too. He’s bolted.”

A hard look came into the other’s eyes. Dim as the light was, it was strong enough to show his expression, and that expression was not an agreeable one.

“That won’t do,” he said, in a metallic voice.

“Now, my dear old horse——”

“It’s no good trying anything like that on me. I want my money, or I’m going to call a policeman. Now, then!”

“But, laddie, be reasonable.”

“Made a mistake in not getting it in advance. But now’ll do. Out with it!”

“But I keep telling you Previn’s bolted!”

“He’s certainly bolted,” I put in, trying to be helpful.

“That’s right, mister,” said a voice at the door. “I met ’im sneakin’ away.”

It was Wilberforce Billson. He stood in the doorway diffidently, as one not sure of his welcome. His whole bearing was apologetic. He had a nasty bruise on his left cheek and one of his eyes was closed, but he bore no other signs of his recent conflict.

Ukridge was gazing upon him with bulging eyes.

“You met him!” he moaned. “You actually met him?”

“R,” said Mr. Billson. “When I was comin’ to the ’all. I seen ’im puttin’ all that money into a liddle bag, and then ’e ’urried off.”

“Good Lord!” I cried. “Didn’t you suspect what he was up to?”

“R,” agreed Mr. Billson. “I always knew ’e was a wrong ’un.”

“Then why, you poor woollen-headed fish,” bellowed Ukridge, exploding, “why on earth didn’t you stop him?”

“I never thought of that,” admitted Mr. Billson, apologetically.

Ukridge laughed a hideous laugh.

“I just pushed ’im in the face,” proceeded Mr. Billson, “and took the liddle bag away from ’im.”

He placed on the table a small weather-worn suitcase that jingled musically as he moved it; then, with the air of one who dismisses some triviality from his mind, moved to the door.

“ ’Scuse me, gents,” said Battling Billson, deprecatingly. “Can’t stop. I’ve got to go and spread the light.”

(Another story by P. G. Wodehouse next month.)

Annotations for this story are elsewhere on this site.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums