Ukridge

by

P. G. Wodehouse

Literary and Cultural References

This is part of an ongoing effort by the members of the Blandings Yahoo! Group to document references, allusions, quotations, etc. in the works of P. G. Wodehouse.

Ukridge was originally annotated by Mark Hodson (aka

The Efficient Baxter). The notes have been reformatted, edited, and extended, but credit goes

to Mark for his original efforts, even while we bear the blame for errors of

fact or interpretation. Notes newly added in 2018–19 are flagged with * instead of a page number reference but can be located by interpolation. Newly revised notes are flagged with ° next to the page number.

Ukridge was originally annotated by Mark Hodson (aka

The Efficient Baxter). The notes have been reformatted, edited, and extended, but credit goes

to Mark for his original efforts, even while we bear the blame for errors of

fact or interpretation. Notes newly added in 2018–19 are flagged with * instead of a page number reference but can be located by interpolation. Newly revised notes are flagged with ° next to the page number.

The stories in Ukridge originally appeared in magazines in 1923–24, as detailed in the heading of the notes for each story below. For more information on variants between versions, see Neil Midkiff’s page of the Wodehouse short stories.

The short story collection was published as Ukridge in the UK by Herbert Jenkins Ltd. on 3 June 1924 and, under the inexplicable title He Rather Enjoyed It, in the US by George H. Doran Co. on 30 July 1925.

Ukridge’s Dog College (pp. 1 to 22)

This story runs from pp. 1 to 22 in the 2000 Penguin edition of Ukridge. It was first published in Cosmopolitan in the US in April 1923 and in the Strand in the UK in May 1923; in book form it appeared in Ukridge (Herbert Jenkins, UK, June 1924) and He Rather Enjoyed It (Doran, US, July 1925).

See the end notes to the Cosmopolitan appearance for more details on the passages and wording unique to that version.

[: P. G. Wodehouse, A Portrait of a Master (1981)]

Stanley Featherstonehaugh Ukridge (p. 1)

The character Ukridge (pronounced “Yewk-ridge”) first appeared in the novel Love Among the Chickens (1906, 1909, 1921). Apart from the present collection, there are Ukridge stories in Lord Emsworth and Others (1937), Eggs, Beans and Crumpets (1940), Nothing Serious (1950) and Plum Pie (1966). The distribution of stories between these books varies between the UK and US, of course! Usborne (Wodehouse at Work to the End) has an interesting chapter comparing the Ukridge of the short stories to Love Among the Chickens. Murphy (In Search of Blandings) has done some detective work into the real prototypes for Ukridge, and claims to have found Aunt Julia’s house.

The origin of the name Ukridge is unclear.

Featherstonehaugh (probably pronounced “Fanshaw”, but reference books give seven accepted pronunciations including “as spelled”) is a Northumbrian surname, from the name of a village near Haltwhistle.

Stanley is a common English surname, which possibly owes its popularity as a boys’ given name in the late nineteenth century to the Welsh-born explorer Henry Morton Stanley (1841–1904).

son of Belial *

See Love Among the Chickens and Biblia Wodehousiana.

pots of money *

Wodehouse’s characters often use this phrase for a fortune: Ukridge again in the 1921 version of Love Among the Chickens, Reggie Pepper in “Doing Clarence a Bit of Good” (1913), and the sibyl in “Pots o’ Money” (1913). Later characters who use the phrase include Judson Coker in Bill the Conqueror, ch. 13.2 (1924); Hugo Carmody in Money for Nothing, ch. 4.5 (1928); Ronnie Fish in Summer Lightning, ch. 2 (1929); Berry Conway in Big Money, ch. 1.2 (1931); Pongo Twistleton in Uncle Fred in the Springtime, ch. 5 (1939); Joss Weatherby in Quick Service, ch. 20 (1940); the narrator speaking of Cosmo Blair in Spring Fever, ch. 10 (1948), Bertie Wooster speaking of Boko Fittleworth in Joy in the Morning, ch. 6 (1947); Barmy Phipps in Barmy in Wonderland, ch. 2 (1952); and Gloria Salt in Pigs Have Wings, ch. 3.2 (1952).

Diego Seguí finds several instances in the late 19th century, including this one from 1873, and a discussion of the origin of the phrase in Notes and Queries from 1899.

fifty thousand pounds *

The Bank of England inflation calculator gives a factor of 59.4 from 1923 to 2018, so in current terms this would be nearly £3 million or US$3.8 million.

half-a-crown (p. 2) °

A coin worth 2 shillings and sixpence, one-eighth of a pound sterling (12.5 p in decimal currency). See Summer Lightning.

sported on the green (p. 2)

It was a summer evening,

Old Kaspar’s work was done,

And he before his cottage door

Was sitting in the sun;

And by him sported on the green

His little grandchild Wilhelmine.

[: After Blenheim 1–7]

wore his school cap *

Reminiscent of Harrison wearing his cap while out of bounds in “The Manœuvres of Charteris”.

flitting about the world like a snipe *

See Sam the Sudden.

Buenos Ayres (p. 2)

Obsolete spelling of Buenos Aires (Argentina), common in the nineteenth century, and still often seen in the names of older institutions.

George Tupper (p. 2)

Tupper is usually claimed to be a Huguenot name, and nothing to do with the reproductive habits of sheep. A Professor Tupper-Smith appears in “A Prisoner of War” (1915).

The only famous bearers of that name sems to have been:

(1) Martin Tupper (1810–1880), author of Proverbial Philosophy, the much-mocked Sophie’s World of the mid-Victorian period.

(2) Sir Charles Tupper was one of the Fathers of Confederation, that bushy-bearded gaggle of nation-builders that, against all the odds, managed to create the dominion of Canada July 1, 1867, blazing the trail for the younger dominions, (Australia, NZ, SA, etc.) to follow in the years to come. When not serving as high commissioner to London, Tupper was a senior cabinet minister in Prime Minister John A. MacDonald’s Tory cabinets (1867–73; 1878–91), finally becoming the country’s sixth Prime Minister in 1896, ten weeks before the Tories were thrashed by Laurier’s Grits in the general election of that year. Unfortunately, Charles Tupper’s periods as High Commissioner in London seem to have been at least a decade before George Tupper would have secured his position in the Foreign Office.

[note by Ian Michaud]

head of the school *

That is, the senior student trusted by the authorities with supervising the other prefects who helped maintain discipline and order among the junior students.

as over a reformed prodigal *

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

Wimbledon Common *

A large open space of heathland in southwestern London, formerly the the property of the Earls Spencer, but designated in 1871 as public parkland for recreation and conservation. The adjacent private homes are naturally desirable residences; see The Mating Season for a list of Wodehouse characters who lived next to the Common.commissionaires (p. 3)

Uniformed doorkeepers, especially outside expensive shops and hotels.

Selfridge’s (p. 3)

The Oxford Street department store was opened by the American retailer H. Gordon Selfridge (1856–1947) in 1909. Selfridge learnt his trade with Marshall Field in Chicago, and caused eyebrows to rise in London with his ideas of shopping as entertainment.

living off the fat of the land *

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

browsing and sluicing *

See Right Ho, Jeeves.

Ichabod (p. 3)

Inglorious. From the name of an Old Testament character (Eli’s grandson) who had the bad luck to be born at the moment that the Philistines captured the Ark of the Covenant, the same day that his father, uncle and grandfather died.

15 Now Eli was ninety and eight years old; and his eyes

were dim, that he could not see.

16 And the man said unto Eli, I am he that came out of the army,

and I fled today out of the army. And he said, What is there done, my

son?

17 And the messenger answered and said, Israel is fled before

the Philistines, and there hath been also a great slaughter among the

people, and thy two sons also, Hophni and Phinehas, are dead, and the

ark of God is taken.

18 And it came to pass, when he made mention of the ark of God,

that he fell from off the seat backward by the side of the gate, and

his neck brake, and he died: for he was an old man, and heavy. And he

had judged Israel forty years.

19 ¶ And his daughter-in-law, Phinehas’ wife, was with child,

near to be delivered: and when she heard the tidings that the ark of

God was taken, and that her father-in-law and her husband were dead,

she bowed herself and travailed; for her pains came upon her.

20 And about the time of her death the women that stood by her

said unto her, Fear not; for thou hast borne a son. But she answered

not, neither did she regard it.

21 And she named the child Ichabod, saying, The glory is departed

from Israel: because the ark of God was taken, and because of her father-in-law

and her husband.

22 And she said, The glory is departed from Israel: for the ark

of God is taken.

[Bible: 1 Samuel 4:15–22] See also Biblia Wodehousiana.

I should have had more faith *

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

Elba ... Napoleon (p. 4)

Napoleon Bonaparte abdicated and was exiled to the Mediterranean island of Elba after the allied forces entered France in 1814. He remained there from the 4th of May, 1814 until the 1st of March, 1815, when the unpopularity of Louis XVIII encouraged him to come back for another go. He landed on French soil at Cannes, where Wodehouse was to live for a while in the 1930s.

Ebury Street (p. 4) °

A mainly-residential street in the Belgravia district of London, behind Victoria coach station.

Bowles (p. 4)

First appears in these stories.

eyes of a lightish green *

Another character with “light green eyes” is Ike Goble, in The Little Warrior (Jill the Reckless, 1920).

eyes that seemed to weigh me … and find me wanting *

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

not at all what I have been accustomed to in the best places *

Wodehouse returns to this later in life, describing the butlers of his Edwardian youth in Over Seventy (1957):

an august figure, weighing seventeen stone or so on the hoof, with mauve cheeks, three chins, supercilious lips and bulging gooseberry eyes that raked you with a forbidding stare . . . “Not at all what we have been accustomed to,” those eyes seemed to say.

Pekingese dogs *

Mark Hodson noted that Wodehouse’s interest in Pekes seems to have started with his marriage in 1914, and certainly he and Ethel owned many Pekes over the years. Among his characters who own Pekingese are Georgiana, Lady Alcester (four in “Company for Gertrude”); Rosie M. Banks (six including Ping-Poo and Wing-Fu in “Bingo and the Peke Crisis”); Billie Bennett (Pinky-Boodles, in Three Men and a Maid); Elizabeth Bottsworth’s hostess (Clarkson, in “The Amazing Hat Mystery”); George Spenlow’s blonde friend (Eisenhower, in “Birth of a Salesman”); Luella Mainprice Jopp (Tinky-Ting, in “The Heel of Achilles”); Mrs. John Smith, the Sausage Chappie’s wife (Marie, in “Archie and the Sausage Chappie”); Beatrice Chavender (Patricia, in Quick Service); Mabel Hobson (Percy the Pup, a gift from Reginald Cracknell, raised by Ginger Kemp in The Adventures of Sally); Celia Todd (Pirbright, in “Tangled Hearts”); Tipton Plimsoll’s aunt Miss Plimsoll (six in “Birth of a Salesman”); Mrs. Spottsworth (Pomona, in Ring for Jeeves/The Return of Jeeves); Julia Purkiss (“Bingo and the Peke Crisis”); Marcella Tyrrwhitt (Reginald, renamed Percival by Beatrice Watterson in “Open House”); Mrs. Herbert J. Rossiter (“The Man Who Gave Up Smoking”); Lady Vera Mace (Sham-Poo, in Big Money); Lulabelle Sprockett (“Feet of Clay”); and of course Julia Ukridge in the present story. Ian Michaud notes that Frederick Mulliner buys a Peke as a present for Jane Oliphant in “Portrait of a Disciplinarian.”

Sheep’s Cray, in Kent (p. 6)

There are a number of Kent villages on what is now the edge of London with names like Foot’s Cray, St. Mary Cray, etc., (cray is an archaic word for chalk, of which there is no shortage in Kent). Sheep’s Cray seems to be fictitious, however. Possibly it was inspired by Sheepscombe (Gloucestershire)?

life is stern and ... earnest (p. 6) °

Tell me not, in mournful numbers,

Life is but an empty dream!

For the soul is dead that slumbers,

And things are not what they seem.

Life is real—life is earnest—

And the grave is not its goal:

Dust thou art, to dust returnest,

Was not spoken of the soul.

Not enjoyment, and not sorrow,

Is our destin’d end or way;

But to act, that each to-morrow

Find us farther than today.

Art is long, and time is fleeting,

And our hearts, though stout and brave,

Still, like muffled drums, are beating

Funeral marches to the grave.

In the world’s broad field of battle,

In the bivouac of Life,

Be not like dumb, driven cattle!

Be a hero in the strife!

Trust no Future, howe’er pleasant!

Let the dead Past bury its dead!

Act—act in the glorious Present!

Heart within, and God o’erhead!

Lives of great men all remind us

We can make our lives sublime,

And, departing, leave behind us

Footsteps on the sands of time.

Footsteps, that, perhaps another,

Sailing o’er life’s solemn main,

A forlorn and shipwrecked brother,

Seeing, shall take heart again.

Let us then be up and doing,

with a heart for any fate;

Still achieving, still pursuing,

Learn to labor and to wait.

(1807–1882) A Psalm of Life

[Knickerbocker Magazine, September 1838, vol. 12, p. 189; updated 2015-12-08 NM; thanks to Dirk Laurie for spotting missing stanza]

sumptuous raiment (p. 6)

Seems to be a literary cliché, rather than a specific allusion. Sir Richard Burton’s overuse of it in his translation of the 1001 Nights may have been responsible for bringing the expression into common use, but he certainly didn’t invent it: the OED cites Alexander Barclay’s Eclogues (ca. 1515).

distinctively individual *

From the advertisements for Fatima cigarettes; see the UCSF library web site for one illustration. Another is at the Stanford University tobacco research site.

bright yellow mackintosh (p. 6)

A waterproof coat. To judge by the colour, probably a sailor’s oilskin coat.

ginger-beer wire (p. 6)

Ginger-beer contains a lot of carbon dioxide under pressure, because most of the fermentation takes place in the bottle. Consequently, it was sold in bottles sealed like champagne bottles with a cork held down by twisted wire. This wire would have been useful for improvised repairs in the days before adhesive tape.

Pince-nez are spectacles without earpieces that clip on to the nose: Ukridge has converted his to ordinary spectacles.

a plaster cast of the Infant Samuel at Prayer *

See The Clicking of Cuthbert and Biblia Wodehousiana.

England paved with Pekingese dogs (p. 7)

The surface area of England is about 130 000 sq km. If we assume that to pave England with Pekingese requires about four dogs per square metre (and ignore the practicalities), Ukridge’s stated business plan would reach this output after the 37th group of dogs.

nine hundred dollars ... Ford car business (p. 8)

James Couzens (1872–1936) was working as a bookkeeper to the Detroit coal-dealer Alexander Malcolmson when Malcolmson and Henry Ford set up the Ford Motor Company in 1903. Couzens scraped together $900 of his own savings and borrowed a further $1500 to buy 24 shares in the new company.

His investment made him a millionaire, and he went into banking and became mayor of Detroit. At the time this story appeared he had just entered the US Senate, which would have brought his story to Wodehouse’s attention.

Charing Cross (p. 8)

Charing Cross station, near Trafalgar Square, is the West End terminus of the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway. It’s a small mystery why Ukridge would take a taxi to Charing Cross rather than travel from the London, Chatham and Dover Railway’s terminus at Victoria, about two minutes’ walk from Ebury Street, starting point for many trains to Kent.

Job ... Bildad (p. 8)

Bildad the Shuhite, presumably one of the descendants of Abraham’s son Shuah, is the second of Job’s (uncomforting) comforters in the Bible (see Job chapters 8, 18 and 25).

Then answered Bildad the Shuhite, and said,

How long wilt thou speak these things?

And how long shall the words of thy mouth be like a strong wind?

Doth God pervert judgment?

Or doth the Almighty pervert justice? (etc.)

[Bible: Job 8:1–3] See also Biblia Wodehousiana.

Ballet Russe (p. 9)

The Ballets Russes company (the name was always given in the plural form) was founded in Paris in 1909 by Serge Diaghilev, and broke up after his death in 1929. Diaghilev worked with all the most famous dancers, choreographers, composers and designers of the early twentieth century, and his company had a huge influence on the development of ballet and music.

Gooch, the grocer (p. 9) °

Gooch is a name that appears quite frequently for minor characters in Wodehouse – Garrison (1991) lists eleven, from a fag in “Educating Aubrey” (1911) to the cook in Uncle Dynamite (1948); the third edition (2020) lists thirteen. In A Damsel in Distress there is a (fictitious) Little Gooch Street.

It is not a particularly uncommon name, but the only real Gooch of any note seems to have been the Chief Mechanical Engineer of the Great Western Railway, Sir Daniel Gooch (1816–1889), often described as “Brunel’s right hand.”

[: Who’s Who in Wodehouse (1991)]

Six pounds, three and a penny (p. 9)

i.e. six pounds, three shillings and one old penny, or roughly 6 pounds, 15.5p in decimal coinage.

Upon my Sam (p. 9)

The origins of this expression seem rather obscure – it may have been popularised by Kipling’s Stalky and Co. (1899), but according to the OED it existed in Devon, at least, before that, so Kipling could have picked it up at school. The similarly obscure “Upon my salmon/Salomon/sang” seem to be much older.

Nickerson (p. 10)

This is the only Nickerson in the canon. It seems to be a fairly common name in the USA (possibly they are all Nixons who have changed their names??), but not often seen in Britain: there is no obvious Wodehouse link.

Kempton Park (p. 10)

Racecourse, opened in 1878 at Sunbury-on-Thames, just outside London.

Now is the time for all good men to come to the aid of the party (p. 11) °

subscription lists ... memorials and presentations (p. 11)

In the early twenties, most school Old Boys’ groups would have been raising money to erect memorials to staff and former pupils killed in the recent war.

declare war on Switzerland (p. 11)

Presumably in response to the Swiss navy’s bombardment of Lyme Regis (cf. The Swoop, ch.3)

San Marino (p. 11)

The tiny republic of San Marino (an enclave within Italy) was technically neutral in both World Wars. However, it did have a government closely allied to Mussolini’s Fascists from the early 1920s until 1943.

cold welsh rabbit (p. 11) °

Welsh rabbit is one of those mysterious names that has no obvious connection with the thing it is describing, in this case grilled cheese on toast. Some sources consider it an ethnic slur implying that the poor Welsh could not even afford rabbit and had to be content with cheese instead. In any event, it is a dish best served hot.

set the parrot on to you *

The first appearance of this story, in Cosmopolitan magazine (US), had “sick the parrot on you” here. It is interesting to note that Ukridge’s future bride Millie has an aunt, Lady Lakenheath, with a parrot too, in “Ukridge Rounds a Nasty Corner.”

like one that on a lonesome road (p. 13)

And now this spell was snapt: once more

I viewed the ocean green,

And look’d far forth, yet little saw

Of what had else been seen—

Like one that on a lonesome road

Doth walk in fear and dread,

And having once turn’d round, walks on,

And turns no more his head;

Because he knows a frightful fiend

Doth close behind him tread.

[: The Rime of the Ancient Mariner VI]

without credit commerce has no elasticity *

Ukridge states this in the same words in the 1921 version of Love Among the Chickens, though not in the earlier 1906 or 1909 versions.

shrubbery *

Amalekites (p. 14)

The descendants of Esau’s son Amalek, who were displaced from Canaan and the Sinai peninsula by the Israelites after a long struggle.

See also Biblia Wodehousiana.

resembled a minor prophet *

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

stuffed eel-skin *

borrowed a dead cat *

The first appearance of this story, in Cosmopolitan magazine (US), omits the word “dead” here, and later in the paragraph, after “parked the dogs in my sitting room,” inserts “unleashed Cuthbert the cat”; the magazine illustration by T. D. Skidmore also shows an indubitably live cat running ahead of Ukridge.

that fellow is the salt of the earth *

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

a beaky nose *

Although the narrator does not see her until a later story, he imagines Aunt Julia in much the same terms as Bertie Wooster uses in describing his Aunt Agatha:

…there’s about five-foot-nine of Aunt Agatha, topped off with a beaky nose, an eagle eye, and a lot of gray hair, and the general effect is pretty formidable.

“Aunt Agatha Makes a Bloomer” (the chapter “Aunt Agatha Speaks Her Mind” in The Inimitable Jeeves, or “Aunt Agatha Takes the Count” in The World of Jeeves)

Ukridge’s Accident Syndicate (pp. 23 to 43)

This story runs from pp. 23 to 43 in the 2000 Penguin edition of Ukridge. It was first published in a shortened version in Cosmopolitan in the US in May 1923 and at full length in the Strand in the UK (as “Ukridge, Teddy Weeks and the Tomato”) in June 1923; in book form it appeared, using the Strand text and the Cosmopolitan title, in Ukridge (Herbert Jenkins, UK, June 1924) and He Rather Enjoyed It (Doran, US, July 1925). °

[: P. G. Wodehouse, A Portrait of a Master (1981) ]

Ukridge, sternest of bachelors (p. 23) °

He was, of course, married to Millie on his previous appearance in Love Among the Chickens. Wodehouse evidently decided that he could do more with the character if he became a bachelor again. [Since he meets and woos Millie in the last of these ten stories, it seems that the stories all predate the events of Love Among the Chickens, as do the Ukridge stories collected in later books, despite the order in which they were published. —NM]

obsequies (p. 23)

Funeral honours – the narrator is using the term ironically.

Number eleven foot (p. 23)

Size 11 in the British system for men’s shoes is roughly equivalent to 12 in the US and 44 or 45 everywhere else. Large feet, however measured.

Barolini’s ... Beak Street (p 23)

Beak Street is a side street off Regent Street in the Soho district of London, a likely place to find a cheap Italian restaurant in those days, and an expensive one today.

According to the Italians I have consulted, the name “Barolini” does not have any particular regional or class associations. The Barolinis to be found on the web all seem to be writers or academics.

a shilling and sixpence (p. 24) °

7.5p in decimal currency(!) [Even applying the inflation factor mentioned above, this is something like £4.35 in modern terms, so still seems quite philanthropic.]

Teddy Weeks (p. 24)

Only appears in this story. The only other Weeks listed in Garrison is the butler in “The Mixer” (1915). There is a Weems in French Leave, of course.

Only a Shop-Girl (p. 24)

Compare the Rosie M. Banks novel Only a Factory Girl, from “Jeeves in the Spring-Time” (revised as the first two chapters of The Inimitable Jeeves). Could perhaps be a reference to Margaret Leahy, a shop-girl from Brixton who, in a flood of publicity, won a competition in the Daily Sketch in 1922 to become a film star.

Victor Beamish (p. 24)

The first of a number of characters in the canon to be called Beamish; the third edition of Who’s Who in Wodehouse lists seven. The most prominent is of course the self-improving author J. Hamilton Beamish (The Small Bachelor).

Sally Beamish may sound as though she should be a Wodehouse character, but is actually a respected Scottish composer.

Beamish is a village in County Durham, now the site of a large open-air museum. Cf. also Lewis Carroll’s use of the word as an adjective (“my beamish boy...”) in “Jabberwocky”.

that picture … in the advertisement pages *

Wodehouse must have known one or more aspiring artists who had to turn to commercial illustration to make a living; several of his characters are in that line of work. Ian Michaud wonders if Wodehouse’s friend and collaborator William Townend did advertisement art as well as book and magazine illustrations.

“In the advertisement pages,” said Annette. “Mr. Sellers drew that picture of the Waukeesy Shoe and the Restawhile Settee and the tin of sardines in the Little Gem Sardine advertisement. He is very good at still life.”

“The Man Upstairs” (1910)

Corky managed to get along by drawing an occasional picture for the comic papers—he had rather a gift for funny stuff when he got a good idea—and doing bedsteads and chairs and things for the advertisements.

“Leave It to Jeeves” (“The Artistic Career of Corky”) (1916)

[Note that the “Corky” above is Bruce Corcoran, aspiring New York portrait painter and friend of Bertie Wooster, not the James “Corky” Corcoran who narrates the Ukridge short stories. He is unnamed in these first two stories anyway; we learn his name in “The Début of Battling Billson” below.]

Audrey Blake’s late father in The Little Nugget, Paul Boielle in “Rough-Hew Them How We Will” (1910), Bunny Farringdon in American editions of Cocktail Time (1958), and Gwladys Pendlebury in “Jeeves and the Spot of Art” (1929) all turn their artistic gifts to advertisements at one time or another.

Piccadilly Magazine (p. 24) °

??? From the few references I have found, it isn’t easy to say whether this really existed, or is meant as a pastiche on the real Strand Magazine (where this story appeared). If it existed, there may have been two or three different, presumably short-lived, publications with this title.

[A list of This Week’s Books in the Saturday Review for 2 September 1899 notes issue no. 1 of The Piccadilly Magazine. The Bulletin of Bibliography and Magazine Notes for January 1916 notes a Piccadilly Magazine published monthly in London, with vol. 1, no. 1 in September 1914. A reference in Neill of Summerhill gives their address as 40 Fleet Street. More possibilities are listed at the FictionMags Index. On the other hand, two 1908 stories in the Strand use the name in an apparently fictional manner. —NM]

Bertram Fox (p. 24) °

Seems to be the only active Fox in the canon [though the late Bingley Fox, author of Sixty Years of Society, is mentioned in magazine versions of “The Awful Gladness of the Mater” (1925)]. Given the next name on this page, it is a reasonable assumption that Wodehouse looked at the lid of his tobacco tin for inspiration: James J. Fox of London have been marketing pipe tobacco since the 1880s.

Wodehouse evidently liked the name Bertram – as well as Bertram Wilberforce Wooster, there is also Bertram Lushington in “The Code of the Mulliners”. It probably comes from the character in Shakespeare’s All’s Well That Ends Well, although there are Bertrams in Scott and Jane Austen too, of course.

Robert Dunhill (p. 24)

The only Dunhill in the canon. Dunhill is a brand of cigarettes and pipe tobacco.

New Asiatic Bank (p. 24)

The name Wodehouse always uses for the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank (now HSBC) where he worked for a couple of years (at a salary of eighty pounds a year) after leaving Dulwich. This reference is a strong hint that we should see this story as set in the London of Wodehouse’s bachelor days and Not George Washington, in other words about 1900 rather than 1923.

Ashes of Remorse (p. 24)

Perhaps another tobacco allusion?

Ashes seem to have been popular in the cinema around this time: the Internet Movie Database lists Ashes of Hope (twice), Ashes of Three, Ashes of Remembrance, Ashes of the Past, Ashes of Love, Ashes of Desire, Ashes of Revenge, Ashes of Vengeance, and Ashes of Doom for the period 1912–1923. But Ashes of Remorse apparently remains unproduced.

Barrow-in-Furness ... Bootle (p. 24)

Barrow is a port and industrial town in Cumbria (formerly Lancashire), chiefly remarkable for its remoteness from anywhere else. There are two Bootles in England – the village of this name in Cumbria is quite close to Barrow, but far too small to have had a theatre, so Wodehouse presumably means the port on Merseyside, a mile or so downstream from Liverpool city centre.

If you accept the hypothesis that the character of Lord Emsworth was inspired in part by the then Duke of Devonshire, it might be interesting to add that the Cavendish family owed much of their wealth to the development of Barrow and the Furness Railway.

Cork Street (p. 25)

Cork Street was the original centre of high-class tailoring in London, where men like Beau Brummel bought their clothes. Savile Row (two streets away) later took over as the focal point of the trade: Cork Street is better known for art galleries today.

Moykoff (p. 25) °

Moykopf (not Moykoff) was the name of a firm of bootmakers with a shop in the Burlington Arcade. They seem to have gone out of business around 1956. [The Cosmopolitan magazine version of this story uses the correct spelling.]

Moses Brothers (p. 25) °

A slightly disguised reference to Moss Bros. of Covent Garden. [The Cosmopolitan magazine version of this story uses the actual name.]

Freddie Lunt (p. 25)

Seems to be the only Lunt in the canon.

The name Lunt is usually said to come from Norse or Swedish words meaning a copse or small wood: there are a number of villages in the north of England with names like Lunt, Lund, Lunds, etc. Of course Lund is also the name of a city in Sweden.

accident insurance *

This is by no means a flight of fancy by Wodehouse. From small beginnings (e.g. a £10 policy for fatal accidents for subscribers of the Sheffield Independent in 1920) the competition between papers led to ever-increasing coverage. See this advertisement (large image, opens in new tab or window) from the Birmingham Gazette, 1 May 1922. [NM]

speaking-tube *

See Leave It to Psmith.

this blighter is a broken reed *

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

our hopes had been built on sand *

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

area *

A railed-off sunken space at the front of a city house, giving access to the basement via steps leading down from the sidewalk level.

Cicero ... Clodius (p. 34)

Cicero and Clodius had a long-running and bitter dispute, which started with the great orator prosecuting Clodius for sacrilege (he had sneaked into a religious ceremony dressed as a woman, in the course of a liaison with Caesar’s wife, Pompeia). Clodius got off by bribing the jury, and later found himself in a position to take revenge by driving Cicero into exile on trumped-up charges and taking possession of his estates. Cicero had the last laugh, however, defending Clodius’s main political opponent, the tribune Milo, after he had killed Clodius, apparently in self-defence.

so yellow and few in the pod *

Yellow here implies lack of courage; few in the pod is an obscure phrase but could well mean a lack of “beans” meaning energy, as in “feeling full of beans.” The probable source is Sinclair Lewis’s 1920 novel Main Street:

“Now, frien’s, there’s some folks so yellow and small and so few in the pod that they go to work and claim that those of us that have the big vision are off our trolleys. They say we can’t make Gopher Prairie, God bless her! just as big as Minneapolis or St. Paul or Duluth.”

When this story appeared in Cosmopolitan magazine, the blurb above the title read “By P. G. Wodehouse, Who Laughs in London and is Heard in Gopher Prairie”—leading one to wonder if this was just coincidence or if the headline writer recognized the quotation. [NM]

Moses on Pisgah (p. 36)

1 And Moses went up from the plains of Moab unto the mountain of Nebo, to the

top of Pisgah, that is over against Jericho: and the Lord showed him all the land of Gilead,

unto Dan,

2 and all Naphtali, and the land of Ephraim, and Manasseh, and all the

land of Judah, unto the utmost sea,

3 and the south, and the plain of the valley of Jericho, the city of palm trees, unto Zoar.

4 And the Lord said unto him, This is the land which I sware unto Abraham, unto Isaac, and

unto Jacob, saying, I will give it unto thy seed: I have caused thee to see it with thine

eyes, but thou shalt not go over thither.

5 So Moses the servant of the Lord died there in the land of Moab, according to the word of

the Lord.

[Bible: Deuteronomy 34:1–5] See also Biblia Wodehousiana.

pawn a banjo *

David Jasen’s P. G. Wodehouse: A Portrait of a Master tells (pp. 34–35) that Wodehouse himself bought a banjo in 1905, but that it was pawned by his colleague and occasional house guest Herbert Westbrook.

eight shillings the quart bottle (p 36)

Eight shillings is 40p.

A normal English quart is two pints, or about 1136ml. However, before metrication, wines and spirits were sold in a measure known as the reputed quart, defined as one-sixth of an imperial gallon, or about 757ml (slightly larger than the standard 750ml wine bottle of today).

Nowadays a bottle of cheap Champagne sells in Britain for about 15 pounds, although other fizzy wines are cheaper: one suspects that Signor Barolini may not have been too fussy about his terminology.

What was actually in the champagne … remains a secret *

The By the Way column in the Globe newspaper for June 13, 1903 (a day on which Wodehouse worked on the column), noted that “the manufacture of weird wines is becoming quite an art” and gave a recipe for imitation Burgundy. The item was sparked by an item in the Lancet of that date titled “Fictitious Wines: Some Interesting Recipes” in which methods of counterfeiting various brands of Champagne are given. [NM]

As late as 1964 in Frozen Assets Jerry Shoesmith and Kay Christopher were served something in a Paris bistro that “at first taste seemed to be carbolic acid but which actually was brandy or something reasonably like it” which Kay speculated “was probably used for taking stains out of serge suits.” [IM]

banana-skin *

See Right Ho, Jeeves.

whip-round *

An appeal to a number of persons for contributions to a fund.

ingenuity of their various competitions *

Satirized by Wodehouse and Westbrook in The Globe By the Way Book; see John Dawson’s article on it for examples.

The Début of Battling Billson (pp. 44 to 69)

This story runs from pp. 44 to 69 in the 2000 Penguin edition of Ukridge. It was first published in Cosmopolitan in the US in June 1923 and in the Strand in the UK in July 1923; in book form it appeared in Ukridge (Herbert Jenkins, UK, June 1924) and He Rather Enjoyed It (Doran, US, July 1925).

Ukridge’s boxing protégé Battling Billson appears here for the first time. He later appeared in “The Return of...” and “The Exit of...,” (both in the present volume) and in “The Come-back of...” in Lord Emsworth and Others. He has a walk-on part in the novel Something Fishy as the brother-in-law of Keggs.

Wodehouse was a keen amateur boxer in his school days. Poor eyesight forced him to abandon the sport, but both professional and amateur boxing feature in many of his stories, and he clearly followed it closely. On his first trip to the US in 1904 he went to meet the boxer “Kid” McCoy in his training camp. See the endnotes to one of the Kid Brady stories for more. °

hair-trigger memories … correspondence courses … Mr. Addison Simms of Seattle *

Only the magazine versions of this story add the two-sentence reference to Addison Simms and the granary deal. The Roth Memory Course was widely advertised in magazines with the tag phrase “Of course I place you! Mr. Addison Sims of Seattle.” Here is a typical ad (magazine scan from Google Books, opens in new browser window or tab).

Saturday, September the tenth (p 44) °

This suggests that the story could be set in 1921, 1910 or 1904, assuming that Wodehouse bothered to check the calendar, which seems unlikely. Corky was therefore born on 8 September 1894, 1883, or 1877, respectively.

(Wodehouse was born on 15 October 1881.)

photographically lined on the tablets of my mind (p. 44) °

One winter—I am shaky in my dates—

Came two starving Tartar minstrels to his gates;

Oh, Allah be obeyed,

How infernally they played!

I remember that they called themselves the “Oüaits.”

Oh! that day of sorrow, misery, and rage,

I shall carry to the Catacombs of Age,

Photographically lined

On the tablet of my mind,

When a yesterday has faded from its page!

Alas! Prince Agib went and asked them in;

Gave them beer, and eggs, and sweets, and scent, and tin.

And when (as snobs would say)

They had “put it all away,”

He requested them to tune up and begin.

[: Bab Ballads – “The Story of Prince Agib” ll. 16–30]

sling or arrow of outrageous Fortune *

Adapted from Hamlet’s “To be or not to be” soliloquy.

put the lid on *

Many of Wodehouse’s characters use this slangy way of referring to “the last straw” or a final stage in things getting worse.

In addition, Bristow wore a small black moustache and a ring, and that, as Psmith informed Mike, put the lid on it.

Psmith in the City (serialized as “The New Fold”, 1908–09)

“I guess that’s put the lid on it,” she said. “It’s too bad of me! Making that kind of a break! Oh, well!”

Della Morrison, in The Prince and Betty (UK text) (1912)

And then I put the lid on it. With the best intentions in the world I got myself into such a mess that I thought the end had come.

The dog narrator of “Breaking into Society” (1915)

Well, that seemed to me to put the lid on it. I didn’t mind a heart-to-heart talk, but this was mere abuse.

Reggie Pepper, in “The Test Case” (1915)

And then, just when I was beginning to think I might safely pop down in that direction and gather up the dropped threads, so to speak, time, instead of working the healing wheeze, went and pulled the most awful bone and put the lid on it. Opening the paper one morning, I read that Mrs. Alexander Worple had presented her husband with a son and heir.

Bertie Wooster, in “Leave It to Jeeves” (1916) (later revised as “The Artistic Career of Corky” in Carry On, Jeeves!)

I know you must have had excellent reasons for soaking him, Jimmy, but it did put the lid on it.

Piccadilly Jim, ch. 25 (1917)

“And that crimson hair! It sort of put the lid on it.”

Archie Moffam’s brother-in-law Bill Brewster, in “Paving the Way for Mabel” (1920)

One may express the thing briefly by saying that, as far as Bream was concerned, Sam’s unconventional appearance put the lid on it.

Three Men and a Maid, ch. 16.5/The Girl on the Boat, ch. 17.6 (1922)

…he had realized that Fate, after being tolerably rough with him all day, had put the lid on it by leading him into his rival’s lair…

Freddie Widgeon, in “Trouble Down at Tudsleigh” (in UK collection Young Men in Spats) (1935)

It was a spectacle that rather put the lid on the shrinking feeling from which I was suffering.

The Code of the Woosters, ch. 9 (1938)

“As a matter of fact, that lily-livered sequence was simply what put the lid on it.”

Uncle Dynamite, ch. 2 (1948)

See also Leave It to Psmith.

bezique (p. 44)

A complicated card game for two players, using either two or four 32-card packs. Baxter in the Blandings stories is an enthusiast.

registering Determination *

See Right Ho, Jeeves.

fruity ex-butler way *

finnan haddie (p. 45)

Finnan haddock (or haddie) is a filletted haddock smoked without additional dye, a traditional Scottish dish.

Gaiety Theatre (p. 46)

The Gaiety Theatre on the Strand (near where Bush House now stands) was one of the most fashionable of Edwardian London. When George Edwardes set it up in the 1880s, he laid great stress on getting the prettiest girls in his chorus. Many of them later married into the aristocracy, as Murphy reports. The original theatre was demolished in 1903, to be replaced by the New Gaiety (closed 1939, demolished 1956).

This is another clue that the events of the Ukridge stories have more to do with Edwardian London than with the twenties.

[: In Search of Blandings (1986) 18–20]

The Coal Hole (p. 46)

This pub, in the Savoy Building at 91–92 Strand, still exists. As well as the cellar bar frequented by Ukridge, there is a street-level bar noted for its original Art Nouveau decoration.

Tod Bingham ... Alf Palmer (p. 46) °

Perhaps Tod is related to the pugnacious East End curate “Beefy” Bingham? There are half a dozen other Binghams in the canon.

Alf Palmer is also presumably fictitious, but the name Palmer, although common in Britain, appears only one other place in the canon, as Bellamy Palmer, owner of a stolen painting by Romney in “Doing Clarence a Bit of Good”.

Hyacinth (p. 48)

There have been lots of real and fictional ships named after flowers, from battle cruisers to Mersey ferries: it’s difficult to guess what might have been the inspiration for Wodehouse’s choice of Hyacinth here. Maybe Conrad’s Narcissus?

trimmers (p. 48)

In a coal-fired ship, the trimmers were men whose job was to go into the coal bunkers and shovel the coal to where it was needed by the firemen (stokers), who fed the actual fires.

In a figurative sense, a trimmer is also someone or something with a lot of fight, or likely to succeed.

A.B.s (p. 48)

“Able-Bodied” seamen – experienced sailors who could “hand, reef and steer”.

the Crown in Kennington (p. 48)

It’s not clear whether Ukridge is referring to a fictitious pub, or to the real Crown in Walworth (does that still count as Kennington?), which was later run by Great Train Robber Robert Welsh.

the White Hart at Barnes (p. 49)

The White Hart (nowadays it is “Ye White Hart”) is by the Thames near Barnes Bridge, the finishing line of the Boat Race.

Wonderland (p. 49) °

A former East End hall at 100 Whitechapel Road, Mile End, London, where many boxing matches took place from the late 1890s until it was destroyed in August 1911 by a mysterious fire. [Another clue for dating these short stories roughly to the Edwardian era.]

under-secretary (p. 49)

Broadly speaking, an under-secretary is two steps from the top of the civil service hierarchy, below the deputy secretary and the permanent secretary of a ministry.

Wilberforce (p. 50)

After William Wilberforce (1759–1833), the politician and Evangelical preacher who was one of the main leaders of the British anti-slavery campaign, and has been held up as a hero to Nonconformist Sunday-school children ever since. Anyone with Wilberforce as a first name must have had parents who were Chapel, and is therefore, almost by definition, working-class.

This doesn’t seem to apply to middle names: Bertram Wilberforce Wooster was, of course, christened in honour of a race horse on which his father won a packet. There was also a Samuel Wilberforce Gosling in the early public school novel The Prefect’s Uncle and, although a mere day boy, he presumably came from middle class stock or higher.

“How about Battling Billson?” *

In the original appearance of this story in Cosmopolitan magazine, Ukridge here asks “How about Battling Nelson?” and it is Corky who comes up with “Battling Billson.” Battling Nelson was the ring name of a real-life fighter; see Sam the Sudden for more on him. It seems plausible that the Cosmopolitan reading was Wodehouse’s original, rather than the familiar version from the Strand and the book collections, for two reasons: Ukridge praises the choice of name as “genius. Sheer genius” which would be effusive even for him if he had come up with the moniker himself; and a few paragraphs later Corky refers to the Battler as “my godchild” which seems odd if Ukridge had been the one to select the name. [NM]

the smile that wins *

Though this phrase appears from time to time in earlier literature and poetry, it was popularized in business and sales training courses in the 1910s, and “it’s the voice with the smile that wins” was used by the Bell telephone companies in the USA from about 1915 to encourage success in sales by telephone. The earliest connection so far discovered of the precise phrase to Pepsodent toothpaste is from 1948, although their ads had mentioned “winning smiles” from at least 1928 onward. Wodehouse titled one of his Mulliner stories “The Smile That Wins” in 1931.

Take him for all in all *

Hamlet, speaking to Horatio of his late father (Act I, sc. ii):

He was a man, take him for all in all,

I shall not look upon his like again.

See Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse.

hearts of oak *

Referring literally to the wood used in British sailing ships and figuratively to the character of the men who sail in them. “Heart of Oak,” the official march of the Royal Navy, was originally written for a 1760 theatrical piece by composer William Boyce and actor David Garrick.

Underground station (p. 52)

If they were travelling from Ebury Street, they would presumably have taken the Metropolitan District Railway (later District Line) from Victoria to Whitechapel (opened 1884) or Mile End (1902).

jellied eels (p. 53) °

Jellied eels are a famous speciality of the East End of London. Wodehouse frequently uses them to stand for working-class East End culture. Lord Ickenham’s fellow Pelican, the Hon. Galahad Threepwood, is often said to have associated with “bookies, jellied-eel sellers and three-card-trick men” in his younger days.

Fresh eels are skinned and boned, then stewed until tender and served cold in a jelly. There seem to be two approaches to preparing them, one of which uses added gelatine and one of which implies that the eels form their own jelly.

Ray Albrektson points out an online video showing a commercial jellied-eel processing plant in East London (with slightly gory views of gutting and chopping eels). The owner explains that a home cook can achieve a light jelly just from the cooked eels, but that his recipe adds gelatine to make a firmer jelly that can hold up to packaging and shipping to other retailers throughout Britain.

science *

In boxing, referring to technique and strategy as opposed to brute strength and endurance. From his earliest writing days, Wodehouse frequently praised science in boxing, both in his sports reporting (here is a 1901 example) and his fiction, including his 1902 novel The Pothunters, in which “the feather-weights gave excellent exhibitions of science” in Chapter I.

whistling ‘Comrades’ (p 54)

Possibly the 1916 song by R. Huntington Woodman?

Online sheet music at Duke University library

that zest for combat which had been so sadly to seek in round one *

An old-fashioned use of the infinitive “to seek” meaning “lacking, absent” here.

“Do It Now” *

See Leave It to Psmith.

the third button of his waistcoat *

See Thank You, Jeeves.

silent, sympathetic Scotch and soda *

Not only artful alliteration, but a double transferred epithet. See Leave It to Psmith.

burned her hand at the jam factory (p. 57)

Scalding was a well-known hazard for jam workers before the introduction of jar-filling machinery.

(My great-great uncle, Arthur Lealand, patented one early type of jar-filler shortly before World War I.)

“Kind hearts,” I urged, “are more than coronets.” *

Regent Grill *

That is, the grill-room (informal restaurant, specializing in steaks, chops, and the like) of the Regent Palace Hotel, built 1914–15 near the north side of Piccadilly Circus, on a triangular site bordered by Glasshouse Street, Sherwood Street, and Brewer Street. The hotel closed in 2006, and the historic listed building was converted into a retail and office complex which opened in 2011; the grill-room was restored in 1930s Art Deco style. An earlier image of the grill room:

See also A Damsel in Distress and Piccadilly Jim, ch. vi.

I had an earnest talk with the poor zimp *

A search of vintage slang dictionaries, as well as the OED, has not turned up a definition for “zimp.” (Ignore the recent entry in the Urban Dictionary online.) The Cosmopolitan magazine version revised this to “simp” (colloquial short version of “simpleton”; earliest OED citation is from 1903 as circus-workers’ slang for an easy mark), and Wodehouse would use the phrase “You poor simp” in Bill the Conqueror (1924), so it is at least plausible that Wodehouse had heard “simp” spoken and then spelled it with a z when at his typewriter.

Ian Michaud notes that Anastatia Bates calls Rodney Spelvin a zimp in “The Purification of Rodney Spelvin” (1925); once again, the American magazine editor (Saturday Evening Post this time) changed the spelling to “simp.”

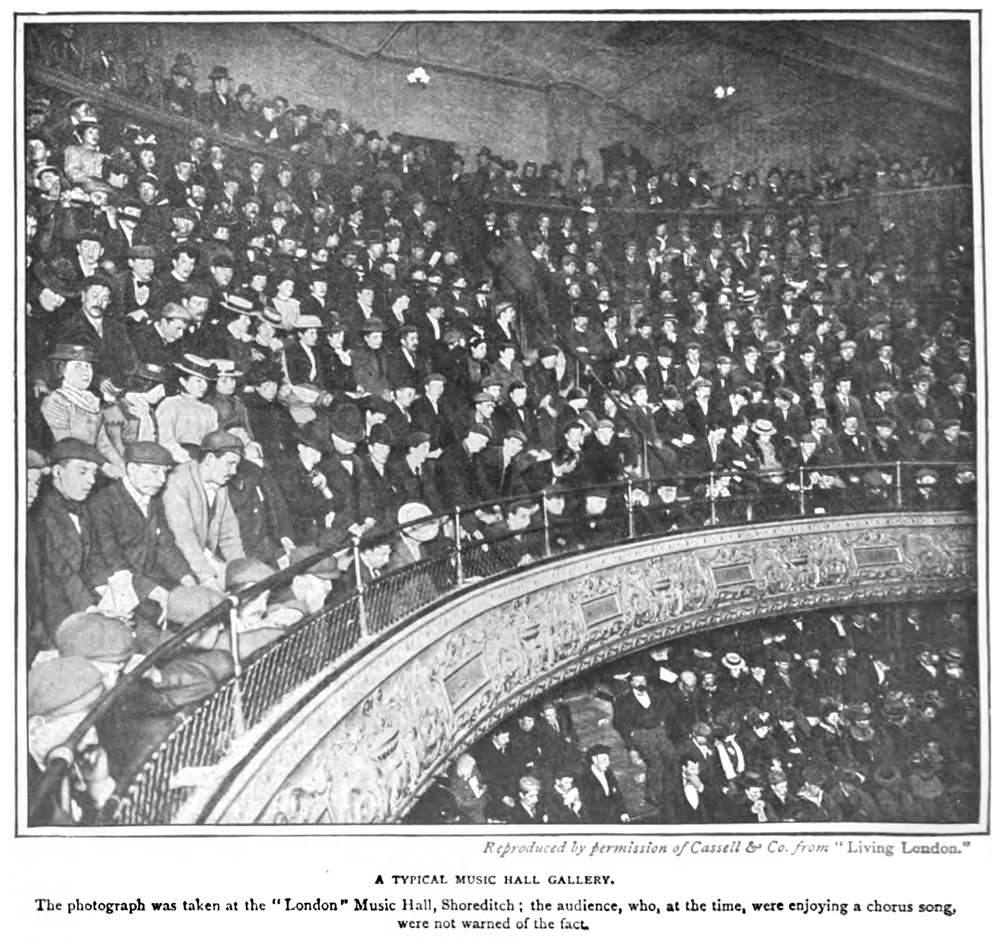

Shoreditch Empire (p. 60) °

The Empire Theatre in Shoreditch was designed by the well-known theatre architect Frank

Matcham in 1894; its first names were the London Theatre of Varieties and the London Music Hall, and it maintained a variety program (music hall/vaudeville as well as sporting events and films) until it was bought out in 1934 and demolished in 1935. It had 2,332 seats (a roomy house indeed, as later mentioned in the story). This photograph appeared in The Playgoer in 1901:

Shoreditch is also in the East End of London, and has a place in theatre history as the original site of “The Theatre”, where the Lord Chamberlain’s Men gave the first performances of many of Shakespeare’s plays. (When a new landlord put the rent up, in 1599, Burbage, who owned the timber, had the theatre dismantled and shipped across the river to Bankside, where it was re-erected as “The Globe”.)

Gatling gun (p. 60)

The first successful design of machine gun, developed by Dr. Richard Gordon Gatling in the USA in the 1860s.

bare-headed *

A fastidious chap like George Tupper would of course wear a hat outside at all times in normal circumstances, so we must infer that he has already arrived at the restaurant and checked his hat, and is now just temporarily at the door looking for the narrator.

picture hat *

A wide-brimmed woman’s hat, typically elaborately decorated with flowers or feathers

Daily Sportsman *

A London paper founded in 1865; the 1911 Encyclopedia Brittanica describes it as the leading paper in its category.

Florence Burns (p. 64) °

Poor Flossie goes through as many different surnames as Aunt Julia’s butler: although she is still called Burns in “The Return of...”, by “The Come-Back of...” she is called Dalrymple; in Something Fishy she has changed her name to Billson for entirely legitimate reasons, but her maiden name has been retrospectively changed to Keggs.

[Barmaids did often adopt a different name for their work; recall that Maudie Beach (later Mrs. Stubbs) worked at the Criterion bar under the nom de guerre of Maudie Montrose, as recalled in Pigs Have Wings. —NM]

Cheese it! *

See Leave It to Psmith.

at each other with a wild surmise *

See Thank You, Jeeves.

that other and sterner bird which haunts those places of entertainment *

Hissing by the audience; see Leave It to Psmith.

A great light shone upon me *

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

First Aid for Dora (pp. 70 to 92)

This story runs from pp. 70 to 92 in the 2000 Penguin edition of Ukridge. It was first published in Cosmopolitan in the US in July 1923 and in the Strand in the UK in August 1923; in book form it appeared in Ukridge (Herbert Jenkins, UK, June 1924) and He Rather Enjoyed It (Doran, US, July 1925).(Wodehouse had used the similar title “First Aid for Looney Biddle” for one of the stories making up The Indiscretions of Archie three years earlier.)

Shaftesbury Avenue (p. 70)

One of the main thoroughfares of the London theatre district, running between Piccadilly Circus and Oxford Street. It is named after the great Victorian social reformer, the 7th Earl of Shaftesbury (1801–1885), who is commemorated by the “Eros” statue in Piccadilly Circus.

matinée audiences (p. 70) °

English theatres traditionally gave afternoon performances on Wednesdays and Saturdays. Wednesday was a half-holiday for many shop-workers and others who had to work on Saturday afternoons.

[In The Girl in Blue veteran thespian Dame Flora Faye called the Wednesday matinée the curse of her life and related the show business anecdote about the actress who was walking past the fish shop and saw all those fishy eyes staring at her. “That reminds me,” she said, “I have a Wednesday matinée.” —IM]

assisting ... to mount an omnibus (p. 70) °

This sounds much more like the horse-buses that dominated the London streets around the turn of the century than the motor buses that had taken over some ten years before this story appeared.

[I am not sure what gave Mark Hodson this impression. The illustration by Reginald Cleaver in the Strand shows Dora stepping up to the back platform of a traditional double-decker London motor bus, with curving back stairs leading to the upper deck. —NM]

Sir Walter Raleigh (p. 70)

Sir Walter Ralegh (or Raleigh), c.1554–1618, Elizabethan poet, courtier and adventurer. Was involved in a certain amount of commercial piracy, and many voyages of exploration, including an abortive attempt to colonise North America.

There is an apocryphal story of him laying his cloak in a puddle to allow Queen Elizabeth to cross dryshod.

“object-matrimony” *

In personal advertisements then and now, “Object: matrimony” is a brief way to express that the advertiser is seeking a spouse rather than merely a temporary romantic fling.

Dora Mason (p. 70) °

Other Masons in the canon include the theatrical agent Mortimer “Pa” Mason (Summer Lightning) and the playwright Wally Mason (The Little Warrior). [A student at Wrykyn in The White Feather and grocery executive Brock Mason in The Coming of Bill/The White Hope round out the list. —NM]

Wodehouse occasionally drops references to the Freemasons into his stories, but there’s no particular reason to see this as one.

Old Tuppy *

That is, George Tupper (see note above at p. 2).

the Apollo (p. 70)

The Apollo theatre, which opened in 1901, is at the Piccadilly Circus end of Shaftesbury Avenue.

steeped to the gills (p. 71)

A variant, probably invented by Wodehouse, on the conventional phrase steeped to the lips, which the OED attributes to Shakespeare. The word gills is often used jocularly to replace lips, cheeks, etc.

Pen and Ink Club (p. 71)

This is clearly a reference to International P.E.N., founded in 1921 by Mrs. C. Dawson Scott. The first president of the London branch was John Galsworthy. Wodehouse, of course, disapproved of writers who took themselves so seriously as to proclaim a political mission for the profession.

A.B.C. shop (p. 71)

The Aerated Bread Company ran a chain of bakeries in the London area. In 1864, the manageress (often mentioned, never named) of the London Bridge branch tried the experiment of serving tea to customers in the back room. It was a success, and soon the ABC were running a chain of tea shops. Their main competitors were Lyons.

Criterion (p. 72)

Bar, restaurant and theatre on Piccadilly Circus. The theatre has the unusual distinction of being largely underground; the bar and restaurant were frequented by a racy set in Edwardian days, but are now very posh – the current chef is one of the few in Britain to have been given three stars by Michelin.

[When he was still known as Piggy Wooster, Lord Yaxley met the future Lady Yaxley serving behind the bar of the Cri. (“Indian Summer of an Uncle”) —IM]

the Derby (p. 72)

The Epsom Derby, founded in 1780 by the 12th Earl of Derby, is one of the premier events in the English horse-racing calendar. The race, which is open only to three-year-old colts, is run each June over a distance of 1 mile 4 furlongs on Epsom Downs in Surrey.

Gunga Din ... a hundred to three (p. 72)

The name of the horse is a reference to Kipling’s famous ballad, of course.

The starting odds mean that anyone who had bet three pounds on this horse would have received a hundred pounds (plus the original stake) if it had come first. This implies that the bookies, at least, did not have a very high opinion of this particular horse’s chances.

’E carried me away

To where a dooli lay,

An’ a bullet come an’ drilled the beggar clean.

’E put me safe inside,

An’ just before ’e died,

“I ’ope you liked your drink,” sez Gunga Din.

So I’ll meet ’im later on

At the place where ’e is gone—

Where it’s always double drill and no canteen;

’E’ll be squattin’ on the coals

Givin’ drink to poor damned souls,

An’ I’ll get a swig in hell from Gunga Din!

Yes, Din! Din! Din!

You Lazarushian-leather Gunga Din!

Though I’ve belted you and flayed you,

By the livin’ Gawd that made you,

You’re a better man than I am, Gunga Din!

[: Gunga Din (last stanza)]

sweepstake (p. 72)

It is common for the members of a group (co-workers, members of a club, etc.) to organise a sweepstake on the result of a big sporting event, usually a horserace. It is a kind of raffle, relying entirely on chance. Each participant puts in the same stake, and draws a ticket with the name of a competitor in the event: the person lucky enough to hold the ticket with the name of the winner gets the pool.

Mario’s (p. 72)

Fictitious – this club also appears in a number of other stories, including Summer Lightning and “The Shadow Passes”. The name suggests Ciro’s in Orange Street, off the Haymarket, but on the strength of the balcony Murphy identifies it as the Café de Paris, which seems to have been one of London’s most fashionable night clubs for much of the twenties and thirties.

[: Reminiscences of the Hon. Galahad Threepwood (1993)]

http://www.mgthomas.co.uk/Dancebands/IndexPages/LondonDancePlaces.htm

Earl of Oxted (p. 74)

Oxted is in Surrey, on the southern fringe of London (it is just outside the ring of the M25 motorway, which is nowadays usually taken to define the limits of the Metropolis).

There does not appear to have been a real Earl of Oxted. The most celebrated Earl of Oxford was Edward de Vere, 17th Earl (1550–1604) whom some promote as the “true author” of Shakespeare’s plays. Wodehouse has fun with such ideas in a number of places in the canon.

In 1925, a couple of years after this was written, the former Liberal prime minister H. H. Asquith (1852–1928) was raised to the peerage as 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith. Asquith knew Wodehouse and was the dedicatee of Meet Mr. Mulliner.

Moth-balls! *

Before the introduction of slowly-sublimating petrochemical mothballs made from naphthalene or 1,4-dichlorobenzene, mothballs were typically made of camphor, a waxy, pungent aromatic solid obtained from vapor distillation of wood chips from certain varieties of trees.

balcony ... not dressed (p. 75)

Not dressed here means ‘not wearing evening dress.’ The dress code at Mario’s is a key element in the plot of Summer Lightning, of course.

James J. Jeffries (p. 76) °

Jeffries (1875–1953) was world heavyweight boxing champion from 1899–1905. Corky and Ukridge are surely far too young to have seen him in the ring, even at his celebrated attempted come-back fight against Jack Johnson in 1910.

[Or maybe not; one point of view is that all the Ukridge short stories take place before his marriage, which was recent in Love Among the Chickens (1906), so are Edwardian in setting. —NM]

Ouida (p. 76) °

Ouida was the pen name of the popular English writer Marie Louise de la Ramée (1839–1908), who published more than forty books including historical-romantic novels, stories set in society life, children’s books, etc., during her long career. Her books had the reputation of being racy and provocative in the Victorian era. Two of her well-known novels, Under Two Flags and A Dog of Flanders, have each been adapted several times for motion pictures.

faultless evening dress (p. 76)

This expression seems to have become a cliché through the works of popular writers of the Edwardian period (e.g. Guy Boothby, Egerton Castle – oddly enough I haven’t found it in Ouida) but more serious writers of the time (Wells, Bennett) also use it. It appears frequently in Wodehouse’s own works, of course.

The use of evening dress to describe men’s evening costume seems to date from around the 1880s – before that an evening dress was a garment worn by a lady.

Hamlet ... full of bread (p. 76)

This may need a bit of unpacking. The allusion is to the scene (Act III, scene 3) where Hamlet comes upon his uncle praying, and resists the urge to avenge his father’s death there and then. Hamlet senior died without the chance to purge his soul by confessing his sins — Full of bread is a reference to Ezekiel 16.49: “Behold, this was the iniquity of thy sister Sodom, pride, fulness of bread, and abundance of idleness...” — and Hamlet junior wants to serve his murderer the same way. (Well, it’s as good an excuse as any other for dragging his indecision out through two more acts...)

Corky, however, need have no such scruples: he has caught Ukridge ‘full of bread’ and could dispatch him there and then in a state of sin.

Hamlet: Now might I do it pat, now he

is praying.

And now I’ll do ’t—And so he goes to heaven;

And so am I reveng’d. That would be scann’d.

A villain kills my father, and for that,

I, his sole son, do this same villain send

To heaven.

Oh, this is hire and salary, not revenge.

He took my father grossly, full of bread,

With all his crimes broad blown, as flush as May;

And how his audit stands who knows save Heaven?

But in our circumstance and course of thought

’Tis heavy with him. And am I then reveng’d,

To take him in the purging of his soul,

When he is fit and season’d for his passage?

No!

Up, sword, and know thou a more horrid hent:

When he is drunk asleep, or in his rage,

Or in the incestuous pleasure of his bed;

At gaming, swearing, or about some act

That has no relish of salvation in ’t;

Then trip him, that his heels may kick at heaven,

And that his soul may be as damn’d and black

As hell, whereto it goes.

[: Hamlet III:iii, ll.76–99] See Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse for more.

perilous stuff that weighs upon the heart (p. 76)

Corky is in Shakespearean mode, but we have moved on to Macbeth and the Physician discussing the problems of mental illness.

Macb. (...)

How does your patient, doctor?

Doct. Not

so sick, my lord,

As she is troubled with thick-coming fancies,

That keep her from her rest.

Macb. Cure

her of that:

Canst thou not minister to a mind diseas’d,

Pluck from the memory a rooted sorrow,

Raze out the written troubles of the brain,

And with some sweet oblivious antidote

Cleanse the stuff’d bosom of that perilous stuff

Which weighs upon the heart?

Doct. Therein

the patient

Must minister to himself.

Macb. Throw physic to the dogs; I’ll

none of it.

[: Macbeth V:iii ll.44–58] See Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse for more.

a toad under the harrow *

The toad beneath the harrow knows

Exactly where each tooth-point goes;

The butterfly upon the road

Preaches contentment to that toad.

a hissing and a byword *

See Right Ho, Jeeves and Biblia Wodehousiana.

newly discovered hieroglyphic *

Recall that King Tutankhamun’s tomb had only been discovered in 1922, the year before this story appeared in magazines, so Egyptology was a timely topic.

ex tempore (p. 82) °

Spontaneous, unprepared. [Spelled “extempore” without italics in both magazine appearances of the story. —NM]

go through fire and water *

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

Tuppy proved a broken reed *

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

miss-in-balk (p. 83)

(More usually spelled miss-in-baulk, as it appears in both magazine versions of this story)

In billiards, a player making an opening stroke from behind the baulk line is not allowed to hit any other ball behind the baulk line. Thus a miss-in-baulk is a deliberate avoidance of something.

Woman’s Sphere (p. 83)

Women’s magazines come and go, so it’s difficult to be certain, but this one seems to be fictitious. The real British magazine Woman’s Realm was published from 1958 to 2001; there also seem to have been a number of magazines in Britain and the US called Woman’s World.

The idea of “Woman’s Sphere” – a narrow area of life within the bounds of which women were supposed to have a pre-eminent role – is particularly associated with Victorian writers like John Ruskin.

Heath House, Wimbledon Common (p. 85)

This house appears under a number of names in the canon. In the later Ukridge stories it is usually ‘The Cedars.’

Murphy has identified it as Gayton Lodge, Parkside, the house (now demolished) of a Mrs. Holland, an aunt of Wodehouse’s cousin, the lawyer Edward Isaac. Isaac, whom Murphy suggests as the source of much of the legal terminology Wodehouse uses, lived nearby in Wimbledon.

[: In Search of Blandings (1986)]

stately homes of Wimbledon (p. 85)

The phrase “stately homes of England” seems to have been invented by Mrs. Hemans of Casabianca (“The boy stood on the burning deck”) notoriety. Noël Coward’s celebrated song of 1938 is a parody. Possibly he was provoked by Mrs. Hemans’s choice of epigraph?

Where’s the coward that would not dare

To fight for such a land? [: Marmion]

The stately Homes of England,

How beautiful they stand!

Amidst their tall ancestral trees,

O’er all the pleasant land.

The deer across their greensward bound

Through shade and sunny gleam,

And the swan glides past them with the sound

Of some rejoicing stream.

The merry Homes of England!

Around their hearths by night,

What gladsome looks of household love

Meet in the ruddy light!

There woman’s voice flows forth in song,

Or childhood’s tale is told,

Or lips move tunefully along

Some glorious page of old.

The blessed Homes of England!

How softly on their bowers

Is laid the holy quietness

That breathes from Sabbath-hours!

Solemn, yet sweet, the church-bell’s chime

Floats through the woods at morn;

All other sounds, in that still time,

Of breeze and leaf are born.

The Cottage Homes of England!

By thousands of her plains,

They are smiling o’er the silvery brooks,

And round the hamlet-fanes.

Through glowing orchards forth they peep,

Each from its nook of leaves,

And fearless there the lowly sleep,

As the bird beneath the eaves.

The free, fair Homes of England!

Long, long in hut and hall,

May hearts of native proof be reared

To guard each hallowed wall!

And green for ever be the groves,

And bright the flowery sod,

Where first the child’s glad spirit loves

Its country and its God!

[ (1793–1835): The Homes of England ]

submerged tenth *

See Something Fresh, and p. 93 below.Miss Watterson (p. 87)

Another Watterson, Beatrice, appears in “Open House” (1932).

The name Watterson seems to be particularly associated with Northern Ireland and the Isle of Man.

Mr. Jevons (p. 87)

Another Jevons is the servant in “Creatures of Impulse” (1914), and Horace Jevons is a former employer of the Efficient Baxter (see “The Crime Wave at Blandings”).

William Stanley Jevons (1835–1882) was a noted economist and logician.

The Heart of Adelaide (p. 89)

Neither the British Library nor the Library of Congress list this title, so we must assume that Miss Ukridge failed to complete it, or had a different title foisted upon her by a publisher.

the Sheik *

Hero of Edith Maude Hull’s 1919 novel The Sheik, famously portrayed in a 1921 silent film by Rudolph Valentino.walked the whole way back (p. 91)

The distance from Wimbledon Common to Ebury Street is about 8km (5 miles).

Sheep’s Cray Cottage (p. 91)

See “Ukridge’s Dog College”.

The Return of Battling Billson (pp. 93 to 117)

This story runs from pp. 93 to 117 in the 2000 Penguin edition of Ukridge. It was first published in Cosmopolitan in the US in August 1923 and in the Strand in the UK in September 1923; in book form it appeared in Ukridge (Herbert Jenkins, UK, June 1924) and He Rather Enjoyed It (Doran, US, July 1925). It is the second story to feature the boxer Battling Billson. It is also the first Ukridge short story in which the name of the narrator is revealed to be James “Corky” Corcoran. (He was merely “Mr. Corcoran” in “First Aid for Dora” and unnamed before that.) °

showing a gold tooth *

References to dental gold in Wodehouse are rare, but generally associated with the lower classes, as here and in:

And, while she may have had a heart of gold, the thing you noticed about her first was that she had a tooth of gold.

Bertie Wooster’s description of Charlotte Corday Rowbotham in “Comrade Bingo” (1922)

His face, besides being freckled, was a dull brick-red in colour; his lips curled back in an unpleasant snarl, showing a gold tooth; and beside him, swaying in an ominous sort of way, hung two clenched red hands about the size of two young legs of mutton.

Looney Biddle, in “First Aid for Looney Biddle” (1920, collected in Indiscretions of Archie).

muscles of his brawny arms ... strong as iron bands (p. 93)

Under a spreading chestnut tree

The village smithy stands;

The smith, a mighty man is he,

With large and sinewy hands;

And the muscles of his brawny arms

Are strong as iron bands.

His hair is crisp, and black, and long,

His face is like the tan;

His brow is wet with honest sweat,

He earns whate’er he can,

And looks the whole world in the face,

For he owes not any man.

[ (1807–1882) The village blacksmith 1–12]

to take mankind for my province (p. 93)

Elsie Bean (Anne-Marie Chanet) suggests that this could be an allusion to Francis Bacon’s “I have taken all knowledge to be my province”, perhaps mixed up with the Roman playwright Terentius’s Homo sum, nil humani a me alienum puto (“I am a man: nothing human is strange to me”).

submerged tenth (p. 93)

The lowest sector of the poor classes — the phrase was popularised by the book In Darkest England and the Way Out (1889) by William Booth, founder of the Salvation Army. Booth argued that one tenth of the British population were living below what we now call the poverty line. Jack London also uses the phrase in his writings on the London poor.

In “The Come-Back of Battling Billson” (1935) Ukridge refers to Battling Billson as “a boneheaded submerged-tenther” in both US and UK magazines, and in the US edition of Eggs, Beans and Crumpets (1940). In Lord Emsworth and Others (1937), “a boneheaded proletarian” is the wording here.

worked in a fried-fish shop *

Kit Malim in Not George Washington (1907) works in a fried fish shop, though in the Tottenham Court Road rather than the East End.

Ratcliff Highway (p. 93) °

One of the main roads in the older part of London’s docks, running from the Tower to Ratcliff (now part of Limehouse). The street was later renamed St George’s Street, and is now known simply as The Highway and designated A1203. Notorious for various brutal murders in Victorian times.

[The Cosmopolitan magazine appearance of the story spells it Ratcliffe, and there is quite a bit of historical background to justify that choice. Both UK and US books follow Strand in the shorter spelling.]

http://www.victorianlondon.org/districts/ratcliffhighway.htm

Prince of Wales (p. 94)

There are many pubs in East London called “The Prince of Wales,” but apparently none of them are on the Ratcliff Highway.

improve the occasion *

From the French profitons de l’occasion: to use a situation as an opportunity for pointing out a moral lesson

standing not upon the order of his going (p. 96)

Lady M. I pray you, speak not; he grows worse and

worse;

Question enrages him. At once, good-night:

Stand not upon the order of your going,

But go at once.

[: Macbeth III:iv, ll.140–143] See Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse for more.

scenario *

That is, the outline or preliminary sketch of a black eye; see Sam the Sudden.

to walk back to Ebury Street *

Depending on where Corky’s flat and the Prince of Wales pub are in their respective streets, this might be anywhere from roughly four to six miles.

“little” *

We know that Ukridge can wear Corky’s dress clothes, so Corky must be almost Ukridge’s size, and Ukridge is “quite six foot two, and tremendously filled out” (according to Corky’s friend Lickford in Love Among the Chickens). So Billson must be massive indeed to consider Corky “little.”

Phillips-Oppenheim-like (p. 99)

E. Phillips Oppenheim (1866–1946), British author of over 150 novels, mostly mysteries or spy stories.

Euston (p. 100)

London terminus of the London & North Western Railway, and starting point for trains to the West Midlands, Lancashire and the West of Scotland.

The original station, built in 1838 for the London & Birmingham Railway and with its entrance marked by a huge Doric triumphal arch, was demolished by British Railways in 1962, to be replaced by a hideous concrete structure.

building on sandy soil *

Evoking the “foolish man, which built his house upon the sand: and the rain descended, and the floods came, and the winds blew, and beat upon that house; and it fell: and great was the fall of it.”

[Bible: Matthew 7:26–27] See also Biblia Wodehousiana.

rat-faced *

Others in the canon described as rat-faced are Rupert Steggles (in “The Great Sermon Handicap”) and the late Rat-Faced Rupert, the Bermondsey Twister, who reformed and became a Salvation Army colonel and the father of Annabel Purvis in “Romance at Droitgate Spa” (1937).

...women removed their hats in Westminster Abbey (p. 102)

Traditionally, men uncovered their heads and women covered theirs when entering a Christian church. The growth of feminism and decline of hat-wearing since 1945 have led to the abhorrence of bare female heads being quietly abandoned, at least in most protestant churches.

homicides *

The use of “homicide” to mean “murderer” (rather than the act of killing another person) has somewhat fallen out of use, but according to the OED is slightly older, dating to the fourteenth century.

The Cosmopolitan editor apparently amended the passage to conform to American usage: “Murderers do not publish programs. I had no notion what homicides were scheduled for today.”

“Speaking as far as I’m personally concerned...” (p. 103)

Flossie’s mother has a number of speech habits that are typical of Northern working-class speech, like transposing them/those and was/were. “Dropping aitches” is something that happens in all types of English speech, but for some reason it is popularly considered a marker of working-class speech, so that in reality people like Flossie’s mother, who want to appear to come from a higher social class, tend to overcompensate and add aitches where they are not needed.

The introduction of redundant words and phrases (e.g. “I’m personally”; “rather prefer”) is also typical of the way pompous but uneducated northerners spoke at the time – I can remember my grandfather (b.1900) talking like this.

However, “keb” (for “cab”) is surely Cockney, rather than northern?

Stepney ... Canning Town (p. 103)

Both areas of East London – Stepney is just north of the Ratcliff Highway, where this story opened; Canning Town somewhat further east, about 15km from Ebury Street.

Canning Town ’Orror ... Jimes Potter (p. 103)

Seems to be fictitious. Notice how young Cecil speaks with a marked Cockney accent, even though he is a stranger to London.

’anged ’im at Pentonville (p. 104)

Pentonville prison was built in 1842, the first British prison to apply Bentham’s “Panopticon” design. After the closure of Newgate prison in 1902, Pentonville took over as the site of executions in the London area, a total of 120 prisoners (including Crippen) being hanged there before capital punishment ended in 1961.

the Bing Street ’Orror (p. 104)

There is currently no Bing Street in London, though there is a Byng Street in Millwall, another area of East End dockland.

...was found in the cellar (p. 104)

This sounds like a reference to the celebrated case of “Doctor” Crippen (1910) – the headless body of Crippen’s wife Cora was found in the cellar of their house in Cambden Town (not Canning Town). Cambden Town is in north London, not far from Euston station.

Arundel Street, Leicester Square (p. 104)