The Strand Magazine, June 1930

THE bar parlour of the Anglers’ Rest was fuller than usual. Our local race meeting had been held during the afternoon, and this always means a rush of custom. In addition to the habitués, that faithful little band of listeners which sits nightly at the feet of Mr. Mulliner, there were present some half-a-dozen strangers. One of these, a fair-haired young Stout and Mild, wore the unmistakable air of a man who has not been fortunate in his selections. He sat staring before him with dull eyes and a drooping jaw, and nothing that his companions could do seemed able to cheer him up.

A genial Sherry and Bitters, one of the regular patrons, eyed the sufferer with bluff sympathy.

“What your friend appears to need, gentlemen,” he said, “is a dose of Mulliner’s Buck-U-Uppo.”

“What’s Mulliner’s Buck-U-Uppo?” asked one of the strangers, a Whisky Sour, interested. “Never heard of it myself.”

Mr. Mulliner smiled indulgently.

“He is referring,” he explained, “to a tonic invented by my brother Wilfred, the well-known analytical chemist. It is not often administered to human beings, having been designed primarily to encourage elephants in India to conduct themselves with an easy nonchalance during the tiger-hunts which are so popular in that country. But occasionally human beings do partake of it, with impressive results. I was telling the company here not long ago of the remarkable effect it had on my nephew Augustine, the curate.”

“It bucked him up?”

“It bucked him up very considerably. It acted on his Bishop, too, when he tried it, in a similar manner. So much so, that that Pastor of Souls immediately went out and painted a statue pink. A deplorable affair. But hushed up, I am glad to say. It is undoubtedly a most efficient tonic, strong and invigorating.”

“How is Augustine, by the way?” asked the Sherry and Bitters.

“Extremely well. I received a letter from him only this morning. I am not sure if I told you, but he is a vicar now, at Walsingford-below-Chiveney-on-Thames. A delightful resort, mostly honeysuckle and apple-cheeked villagers.”

“Anything been happening to him lately?”

“It is strange that you should ask that,” said Mr. Mulliner, finishing his hot Scotch and lemon and rapping gently on the table. “In this letter to which I allude he has quite an interesting story to relate. It deals with the loves of Ronald Bracy-Gascoigne and Hypatia Wace. Hypatia is a school friend of my nephew’s wife. She has been staying at the Vicarage, nursing her through a sharp attack of mumps. She is also the niece and ward of Augustine’s superior of the Cloth, the Bishop of Stortford.”

“Was that the Bishop who took the Buck-U-Uppo?”

“The same,” said Mr. Mulliner. “As for Ronald Bracy-Gascoigne, he is a young man of independent means who resides in the neighbourhood. He is, of course, one of the Berkshire Bracy-Gascoignes.”

“Ronald,” said a Lemonade and Angostura, thoughtfully. “Now, there’s a name I never cared for.”

“In that respect,” said Mr. Mulliner, “you differ from Hypatia Wace. She thought it swell. She loved Ronald Bracy-Gascoigne with all the fervour of a young girl’s heart, and they were provisionally engaged to be married. Provisionally, I say, because, before the firing-squad could actually be assembled, it was necessary for the young couple to obtain the consent of the Bishop of Stortford. Mark that, gentlemen. Their engagement was subject to the Bishop of Stortford’s consent. This was the snag that protruded jaggedly from the middle of the primrose path of their happiness, and for quite a while it seemed as if Cupid must inevitably stub his toe on it.”

I WILL select as the point at which to begin my tale (said Mr. Mulliner) a lovely evening in June, when all Nature seemed to smile and the rays of the setting sun fell like molten gold upon the picturesque garden of the Vicarage at Walsingford-below-Chiveney-on-Thames. On a rustic bench beneath a spreading elm, Hypatia Wace and Ronald Bracy-Gascoigne watched the shadows lengthening across the smooth lawn: and to the girl there appeared something symbolical and ominous about this creeping blackness. She shivered. To her, it was as if the sun-bathed lawn represented her happiness and the shadows the doom that was creeping upon it.

“Are you doing anything at the moment, Ronnie?” she asked.

“Eh?” said Ronald Bracy-Gascoigne. “What? Doing anything? No, I’m not doing anything.”

“Then kiss me,” cried Hypatia.

“Right-ho,” said the young man. “I see what you mean. Rather a scheme. I will.”

He did so: and for some moments they clung together in a close embrace. Then Ronald, releasing her gently, began to slap himself between the shoulder-blades.

“Beetle or something down my back,” he explained. “Probably fell off the tree.”

“Kiss me again,” whispered Hypatia.

“In one second, old girl,” said Ronald. “The instant I’ve dealt with this beetle or something. Would you mind just fetching me a whack on about the fourth knob of the spine, reading from the top downwards? I fancy that would make it think a bit.”

Hypatia uttered a sharp exclamation.

“Is this a time,” she cried, passionately, “to talk of beetles?”

“Well, you know, don’t you know,” said Ronald, with a touch of apology in his voice, “they seem rather to force themselves on your attention when they get down your back. I dare say you’ve had the same experience yourself. I don’t suppose in the ordinary way I mention beetles half-a-dozen times a year, but—I should say the fifth knob would be about the spot now. A good, sharp slosh with plenty of follow-through ought to do the trick.”

Hypatia clenched her hands. She was seething with that febrile exasperation which, since the days of Eve, has come upon women who find themselves linked to a cloth-head.

“You poor sap,” she said tensely. “You keep babbling about beetles, and you don’t appear to realize that, if you want to kiss me, you’d better cram in all the kissing you can now, while the going is good. It doesn’t seem to have occurred to you that after to-night you’re going to fade out of the picture.”

“Oh, I say, no! Why?”

“My Uncle Percy arrives this evening.”

“The Bishop?”

“Yes. And my Aunt Priscilla.”

“And you think they won’t be any too frightfully keen on me?”

“I know they won’t. I wrote and told them we were engaged, and I had a letter this afternoon saying you wouldn’t do.”

“No, I say, really? Oh, I say, dash it!”

“ ‘Out of the question,’ my uncle said. And underlined it.”

“Not really? Not absolutely underlined it?”

“Yes. Twice. In very black ink.”

A cloud darkened the young man’s face. The beetle had begun to try out a few dance-steps on the small of his back, but he ignored it. A Tiller troupe of beetles could not have engaged his attention now.

“But what’s he got against me?”

“Well, for one thing he has heard that you were sent down from Oxford.”

“But all the best men are. Look at what’s-his-name. Chap who wrote poems. Shellac, or some such name.”

“And then he knows that you dance a lot.”

“What’s wrong with dancing? I’m not very well up in these things, but didn’t David dance before Saul? Or am I thinking of a couple of other fellows? Anyway, I know that somebody danced before somebody and was extremely highly thought of in consequence.”

“David——”

“I’m not saying it was David, mind you. It may quite easily have been Samuel.”

“David——”

“Or even Nimshi, the son of Bimshi, or somebody like that.”

“David, or Samuel, or Nimshi, the son of Bimshi,” said Hypatia, “did not dance at the Home From Home.”

Her allusion was to the latest of those frivolous night-clubs which spring up from time to time on the reaches of the Thames which are within a comfortable distance from London. This one stood some half a mile from the Vicarage gates.

“Is that what the Bish is beefing about?” demanded Ronald, genuinely astonished. “You don’t mean to tell me he really objects to the Home From Home? Why, a cathedral couldn’t be more rigidly respectable. Does he realize that the place has only been raided twice in the whole course of its existence? A few simple words of explanation will put all this right. I’ll have a talk with the old boy.”

Hypatia shook her head.

“No,” she said. “It’s no use talking. He has made his mind up. One of the things he said in his letter was that, rather than see me married to a vapid and irreflective worldling like you, he would wish to see me turned into a pillar of salt like Lot’s wife. Genesis xix., 26. And nothing could be fairer than that, could it? So what I would suggest is that you start immediately to fold me in your arms and cover my face with kisses. It’s the last chance you’ll get.”

The young man was about to follow her advice, for he could see that there was much in what she said; but at this moment there came from the direction of the house the sound of a manly voice trolling the Psalm for the Second Sunday after Septuagesima. And an instant later their host, the Rev. Augustine Mulliner, appeared in sight. He saw them and came hurrying across the garden, leaping over the flower-beds with extraordinary vivacity.

“Amazing elasticity that bird has, both physical and mental,” said Ronald Bracy-Gascoigne, eyeing Augustine, as he approached, with a gloomy envy. “How does he get that way?”

“He was telling me last night,” said Hypatia. “He has a tonic which he takes regularly. It is called Mulliner’s Buck-U-Uppo, and acts directly upon the red corpuscles.”

“I wish he would give the Bish a swig of it,” said Ronald, moodily. A sudden light of hope came into his eyes. “I say, Hyp, old girl,” he exclaimed. “That’s rather a notion. Don’t you think it’s rather a notion? It looks to me like something of an idea. If the Bish were to dip his beak into the stuff, it might make him take a brighter view of me.”

Hypatia, like all girls who intend to be good wives, made it a practice to look on any suggestions thrown out by her future lord and master as fatuous and futile.

“I never heard anything so silly,” she said.

“Well, I wish you would try it. No harm in trying it, what?”

“Of course, I shall do nothing of the kind.”

“Well, I do think you might try it,” said Ronald. “I mean, try it, don’t you know.”

He could speak no further on the matter, for now they were no longer alone. Augustine had come up. His kindly face looked grave.

“I say, Ronnie, old bloke,” said Augustine, “I don’t want to hurry you, but I think I ought to inform you that the Bishes, male and female, are even now on their way up from the station. I should be popping, if I were you. The prudent man looketh well to his going. Proverbs xiv., 15.”

“All right,” said Ronald, sombrely. “I suppose,” he added, turning to the girl, “you wouldn’t care to sneak out to-night and come and have one final spot of shoe-slithering at the Home From Home? It’s a gala night. Might be fun, what? Give us a chance of saying good-bye properly, and all that.”

“I never heard anything so silly,” said Hypatia, mechanically. “Of course I’ll come.”

“Right-ho. Meet you down the road about twelve, then,” said Ronald Bracy-Gascoigne.

He walked swiftly away, and presently was lost to sight behind the shrubbery. Hypatia turned with a choking sob, and Augustine took her hand and squeezed it gently.

“Cheer up, old onion,” he urged. “Don’t lose hope. Remember, many waters cannot quench love. Song of Solomon viii., 7.”

“I don’t see what quenching love has got to do with it,” said Hypatia, peevishly. “Our trouble is that I’ve got an uncle, complete with gaiters and hat with bootlaces on it, who can’t see Ronnie with a telescope.”

“I know.” Augustine nodded sympathetically. “And my heart bleeds for you. I’ve been through all this sort of thing myself. When I was trying to marry Jane, I was stymied by a father-in-law-to-be who had to be seen to be believed. A chap, I assure you, who combined chronic shortness of temper with the ability to bend pokers round his biceps. Tact was what won him over, and tact is what I propose to employ in your case. I have an idea at the back of my mind. I won’t tell you what it is, but you may take it from me it’s the real tabasco.”

“How kind you are, Augustine!” sighed the girl.

“It comes from mixing with Boy Scouts. You may have noticed that the village is stiff with them. But don’t you worry, old girl. I owe you a lot for the way you’ve looked after Jane these last weeks, and I’m going to see you through. If I can’t fix up your little affair, I’ll eat my Hymns, Ancient and Modern. And uncooked at that.”

And with these brave words Augustine Mulliner turned two hand-springs, vaulted over the rustic bench, and went about his duties in the parish.

AUGUSTINE was rather relieved, when he came down to dinner that night, to find that Hypatia was not to be among those present. The girl was taking her meal on a tray with Jane, his wife, in the invalid’s bedroom, and he was consequently able to embark with freedom on the discussion of her affairs. As soon as the servants had left the room, accordingly, he addressed himself to the task.

“Now listen, you two dear good souls,” he said. “What I want to talk to you about, now that we are alone, is this business of Hypatia and Ronald Bracy-Gascoigne.”

The Lady Bishopess pursed her lips, displeased. She was a woman of ample and majestic build. A friend of Augustine’s, who had been attached to the Tank Corps during the War, had once said that he knew nothing that brought the old days back more vividly than the sight of her. All she needed, he maintained, was a steering-wheel and a couple of machine-guns, and you could have moved her up into any Front Line and no questions asked.

“Please, Mr. Mulliner!” she said, coldly.

Augustine was not to be deterred. Like all the Mulliners, he was at heart a man of reckless courage.

“They tell me you are thinking of bunging a spanner into the works,” he said. “Not true, I hope?”

“Quite true, Mr. Mulliner. Am I not right, Percy?”

“Quite,” said the Bishop.

“We have made careful inquiries about the young man, and are satisfied that he is entirely unsuitable.”

“Would you say that?” said Augustine. “A pretty good egg, I’ve always found him. What’s your main objection to the poor lizard?”

The Lady Bishopess shivered.

“We learn that he is frequently to be seen dancing at an advanced hour, not only in gilded London night-clubs, but even in what should be the purer atmosphere of Walsingford-below-Chiveney-on-Thames. There is a resort in this neighbourhood known, I believe, as the Home From Home.”

“Yes, just down the road,” said Augustine. “It’s a gala night to-night, if you cared to look in. Fancy dress optional.”

“I understand that he is to be seen there almost nightly. Now, against dancing quâ dancing,” proceeded the Lady Bishopess, “I have nothing to say. Properly conducted, it is a pleasing and innocuous pastime. In my own younger days I myself was no mean exponent of the Polka, the Schottische, and the Roger de Coverley. Indeed, it was at a Dance in Aid of the Distressed Daughters of Clergymen of the Church of England Relief Fund that I first met my husband.”

“Really?” said Augustine. “Well, cheerio!” he said, draining his glass of port.

“But dancing, as the term is understood nowadays, is another matter. I have no doubt that what you term a gala night would prove, on inspection, to be little less than one of those orgies where perfect strangers of both sexes unblushingly throw coloured celluloid balls at one another, and in other ways behave in a manner more suitable to the Cities of the Plain than to our dear England. No, Mr. Mulliner, if this young man, Ronald Bracy-Gascoigne, is in the habit of frequenting places of the type of the Home From Home, he is not a fit mate for a pure young girl like my niece Hypatia. Am I not correct, Percy?”

“Perfectly correct, my dear.”

“Oh, right-ho, then,” said Augustine, philosophically, and turned the conversation to the forthcoming Pan-Anglican synod.

LIVING in the country had given Augustine Mulliner the excellent habit of going early to bed. He had a sermon to compose on the morrow, and in order to be fresh and at his best in the morning, he retired shortly before eleven. And, as he had anticipated an unbroken eight hours of refreshing sleep, it was with no little annoyance that he became aware, towards midnight, of a hand on his shoulder, shaking him. Opening his eyes, he found that the light had been switched on and that the Bishop of Stortford was standing at his bedside.

“Hullo!” said Augustine. “Anything wrong?”

The Bishop smiled genially, and hummed a bar or two of the hymn for those of riper years at sea. He was plainly in excellent spirits.

“Nothing, my dear fellow,” he replied. “In fact, very much the reverse. How are you, Mulliner?”

“I feel fine, Bish.”

“I’ll bet you two chasubles to a hassock you don’t feel as fine as I do,” said the Bishop. “I haven’t felt like this since Boat Race Night of the year 1893. Wow!” he continued. “Whoopee! How goodly are thy tents, O Jacob, and thy tabernacles, O Israel! Numbers xxiv., 5.” And, gripping the rail of the bed, he endeavoured to balance himself on his hands with his feet in the air.

Augustine looked at him with growing concern. He could not rid himself of a curious feeling that there was something sinister behind this ebullience. Often before he had seen his guest in a mood of dignified animation, for the robust cheerfulness of the other’s outlook was famous in ecclesiastical circles. But here, surely, was something more than dignified animation.

“Yes,” proceeded the Bishop, completing his gymnastics and sitting down on the bed, “I feel like a fighting-cock, Mulliner. I am full of beans. And the idea of wasting the golden hours of the night in bed seemed so silly that I had to get up and look in on you for a chat. Now, this is what I want to speak to you about, my dear fellow. I wonder if you recollect writing to me—round about Epiphany, it would have been—to tell me of the hit you made in the Boy Scouts’ pantomime here? You played Sindbad the Sailor, if I am not mistaken?”

“That’s right.”

“Well, what I came to ask, my dear Mulliner, was this. Can you, by any chance, lay your hand on that Sindbad costume? I want to borrow it, if I may.”

“What for?”

“Never mind what for, Mulliner. Sufficient for you to know that motives of the soundest Churchmanship render it essential for me to have that suit.”

“Very well, Bish. I’ll find it for you to-morrow.”

“To-morrow will not do. This dilatory spirit of putting things off, this sluggish attitude of laisser-faire and procrastination,” said the Bishop, frowning, “are scarcely what I expected to find in you, Mulliner. But there,” he added, more kindly, “let us say no more. Just dig up that Sindbad costume, and look slippy about it, and we will forget the whole matter. What does it look like?”

“Just an ordinary sailor-suit, Bish.”

“Excellent. Some species of head-gear goes with it, no doubt?”

“A cap with ‘H.M.S. Blotto’ on the band.”

“Admirable. Then, my dear fellow,” said the Bishop, beaming, “if you will just let me have it, I will trouble you no further to-night. Your day’s toil in the vineyard has earned repose. The sleep of the labouring man is sweet. Ecclesiastes v., 12.”

As the door closed behind his guest, Augustine was conscious of a definite uneasiness. Only once before had he seen his spiritual superior in quite this exalted condition. That had been two years ago, when they had gone down to Harchester College to unveil the statue of Lord Hemel of Hempstead. On that occasion, he recollected, the Bishop, under the influence of an overdose of Buck-U-Uppo, had not been content with unveiling the statue. He had gone out in the small hours of the night and painted it pink. Augustine could still recall the surge of emotion which had come upon him when, leaning out of the window, he had observed the prelate climbing up the waterspout on his way back to his room. And he still remembered the sorrowful pity with which he had listened to the other’s lame explanation that he was a cat belonging to the cook.

Sleep, in the present circumstances, was out of the question. With a pensive sigh, Augustine slipped on a dressing-gown and went downstairs to his study. It would ease his mind, he thought, to do a little work on that sermon of his.

Augustine’s study was on the ground floor, looking on to the garden. It was a lovely night, and he opened the French windows, the better to enjoy the soothing scents of the flowers beyond. Then, seating himself at his desk, he began to work.

The task of composing a sermon which should practically make sense and yet not be above the heads of his rustic flock was always one that caused Augustine Mulliner to concentrate tensely. Soon he was lost in his labour and oblivious to everything but the problem of how to find a word of one syllable that meant Supralapsarianism. A glaze of preoccupation had come over his eyes, and the tip of his tongue, protruding from the left corner of his mouth, revolved in slow circles.

FROM this waking trance he emerged slowly to the realization that somebody was speaking his name and that he was no longer alone in the room.

Seated in his arm-chair, her lithe young body wrapped in a green dressing-gown, was Hypatia Wace.

“Hullo!” said Augustine, staring. “You here?”

“Hullo!” said Hypatia. “Yes, I’m here.”

“I thought you had gone to the Home From Home to meet Ronald.”

Hypatia shook her head.

“We never made it,” she said. “Ronnie rang up to say that he had had a private tip that the place was to be raided to-night. So we thought it wasn’t safe to start anything.”

“Quite right,” said Augustine, approvingly. “Prudence first. Whatsoever thou takest in hand, remember the end and thou shalt never do amiss.”

Hypatia dabbed at her eyes with her handkerchief.

“I couldn’t sleep, and I saw the light, so I came down. I’m so miserable, Augustine.”

“There, there!” said Augustine. “Everything’s going to be hotsy-totsy.”

“You don’t think so, really, do you?”

“Of course I do,” said Augustine, heartily. “Shall I tell you a little secret?”

“What?”

“It’s just this. I have been giving your case a good deal of thought, and, analysing the position, I came to the conclusion that what the Lady Bish thinks to-day, the Bish will think to-morrow. In other words, if we can win her over, he will give his consent in a minute. Am I wrong or am I right?”

Hypatia nodded.

“Yes,” she said. “That’s right, as far as it goes. Uncle Percy always does do what Aunt Priscilla tells him to. But——”

“But where does that get us, you were about to say? I’ll tell you,” said Augustine. “I have made an ingenious and strategic move. Just before she went to bed, I slipped a few drops of the Buck-U-Uppo into your Aunt Priscilla’s hot milk. You will see the results to-morrow. Mulliner’s Buck-U-Uppo changes the whole mental outlook.”

“You did?” cried Hypatia.

“I did,” said Augustine.

“How very odd!” said Hypatia. “Odd that you should have thought of that, too, I mean.”

An icy hand seemed to clutch at Augustine’s heart.

“Too?” he stammered.

“Yes,” said Hypatia. “I must say I never thought much of it as a scheme, but Ronnie seemed keen on it, so I felt I might as well give it a whirl. I slipped some Buck-U-Uppo into Aunt Priscilla’s hot milk, and some into Uncle Percy’s toddy, too.”

Augustine could scarcely speak, but he contrived to put one question.

“How much?”

“Oh, not much,” said Hypatia. “I didn’t want to poison the dear old things. About a tablespoonful apiece.”

A shuddering groan came raspingly from Augustine’s lips.

“Are you aware,” he said, in a low, toneless voice, “that the medium dose for an adult elephant is one teaspoonful?”

“No!”

“Yes.” He clutched his hair. “No wonder the Bishop seemed a little strange in his manner just now.”

“Did he seem strange in his manner?”

Augustine nodded dully.

“He came into my room and did hand-springs on the end of the bed and went away with my Sindbad the Sailor suit,” he said.

“What did he want that for?”

Augustine shuddered.

“I scarcely dare to face the thought,” he said, “but can he have been contemplating a visit to the Home From Home? It is gala night, remember.”

“Why, of course,” said Hypatia. “And that must have been why Aunt Priscilla came to me about an hour ago and asked me if I could lend her my Columbine costume.”

“She did!” cried Augustine.

“Certainly she did. I couldn’t think what she wanted it for. But now, of course, I see.”

Augustine uttered a moan that seemed to come from the depths of his soul.

“Run up to her room and see if she is still there,” he said. “If I’m not very much mistaken, we have sown the wind and we shall reap the whirlwind. Hosea viii., 7.”

The girl hurried away, and Augustine began to pace the floor feverishly. He had completed five laps and was beginning a sixth, when there was a noise outside the French windows and a sailorly form shot through and fell panting into the arm-chair.

“Bish!” cried Augustine.

The Bishop waved a hand, to indicate that he would be with him as soon as he had attended to this matter of taking in a fresh supply of breath, and continued to pant. Augustine watched him, deeply concerned. There was a shop-soiled look about his guest. Part of the Sindbad costume had been torn away as if by some irresistible force, and the hat was battered. His worst fears appeared to have been realized.

“Bish!” he cried. “What has been happening?”

The Bishop sat up. He was breathing more easily now, and a pleasant, almost complacent, look had come into his face.

“Woof!” he said. “Some binge!”

“Tell me what happened,” pleaded Augustine, agitated.

The Bishop reflected, arranging his facts in chronological order.

“Well,” he said, “when I got to the Home From Home, everybody was dancing. Nice orchestra. Nice tune. Nice floor. So I danced, too.”

“You danced?”

“Certainly I danced, Mulliner,” replied the Bishop, with a dignity that sat well upon him. “A hornpipe. I consider it the duty of the higher clergy on these occasions to set an example. You didn’t suppose I would go to a place like the Home From Home to play solitaire? Harmless relaxation is not forbidden, I believe?”

“But can you dance?”

“Can I dance?” said the Bishop. “Can I dance, Mulliner? Have you ever heard of Pavlova?”

“Yes.”

“My stage name,” said the Bishop.

Augustine swallowed tensely.

“Whom did you dance with?” he asked.

“At first,” said the Bishop, “I danced alone. But then, most fortunately, my dear wife arrived, looking perfectly charming in some sort of filmy material, and we danced together.”

“You danced together?”

“We did.”

“But wasn’t she surprised to see you there?”

“Not in the least. Why should she be?”

“Oh, I don’t know.”

“Then why did you put the question?”

“I wasn’t thinking.”

“Always think before you speak, Mulliner,” said the Bishop, reprovingly.

The door opened, and Hypatia hurried in.

“She’s not——” She stopped. “Uncle!” she cried.

“Ah, my dear,” said the Bishop. “But I was telling you, Mulliner. After we had been dancing for some time, a most annoying thing occurred. Just as we were enjoying ourselves—everybody cutting up and having a good time—who should come in but a lot of interfering policemen. A most brusque and unpleasant body of men. Inquisitive, too. One of them kept asking me my name and address. But I soon put a stop to all that sort of nonsense. I plugged him on the jaw.”

“You plugged him on the jaw?”

“I plugged him on the jaw, Mulliner. That’s when I got this suit torn. The fellow was annoying me intensely. He ignored my repeated statement that I gave my name and address only to my oldest and closest friends, and had the audacity to clutch me by what I suppose a costumier would describe as the slack of my garment. Well, naturally, I plugged him on the jaw. I come of a fighting line, Mulliner. My ancestor, Bishop Odo, was famous in William the Conqueror’s day for his work with the battle-axe. So I biffed this bird. And did he take a toss? Ask me!” said the Bishop, chuckling contentedly.

Augustine and Hypatia exchanged glances.

“But, uncle——” began Hypatia.

“Don’t interrupt, my child,” said the Bishop. “I cannot marshal my thoughts if you persist in interrupting. Where was I? Ah, yes. Well, then the already existing state of confusion grew intensified. The whole tempo of the proceedings became, as it were, quickened. Somebody turned out the lights, and somebody else upset a table, and I decided to come away.” A pensive look flitted over his face. “I trust,” he said, “that my dear wife also contrived to leave without undue inconvenience. The last I saw of her she was diving through one of the windows in a manner which, I thought, showed considerable lissomness and resource. Ah, here she is, and looking none the worse for her adventures. Come in, my dear. I was just telling Hypatia and our good host here of our little evening from home.”

The Lady Bishopess stood breathing heavily. She was not in the best of training. She had the appearance of a Tank which is missing on one cylinder.

“Save me, Percy,” she gasped.

“Certainly, my dear,” said the Bishop, cordially. “From what?

In silence the Lady Bishopess pointed at the window. Through it, like some figure of doom, was striding a policeman. He, too, was breathing in a labored manner, like one touched in the wind.

The Bishop drew himself up.

“And what, pray,” he asked, coldly, “is the meaning of this intrusion?”

“Ah!” said the policeman.

He closed the windows and stood with his back against them.

It seemed to Augustine that the moment had arrived for a man of tact to take the situation in hand.

“Good evening, constable,” he said, genially. “You appear to have been taking exercise. I have no doubt that you would enjoy a little refreshment.”

The policeman licked his lips, but did not speak.

“I have an excellent tonic here in my cupboard,” proceeded Augustine, “and I think you will find it most restorative. I will mix it with a little seltzer.”

The policeman took the glass, but in a preoccupied manner. His attention was still riveted on the Bishop and his consort.

“Caught you, have I?” he said.

“I fail to understand you, officer,” said the Bishop, frigidly.

“I’ve been chasing her,” said the policeman, pointing to the Lady Bishopess, “a good mile it must have been.”

“Then you acted,” said the Bishop, severely, “in a most offensive and uncalled-for way. On her physician’s recommendation, my dear wife takes a short cross-country run each night before retiring to rest. Things have come to a sorry pass if she cannot follow her doctor’s orders without being pursued—I will use a stronger word: chivvied—by the constabulary.”

“And it was by her doctor’s orders that she went to the Home From Home, eh?” said the policeman, keenly.

“I shall be vastly surprised to learn,” said the Bishop, “that my dear wife has been anywhere near the resort you mention.”

“And you were there, too. I saw you.”

“Absurd!”

“I saw you punch Constable Booker on the jaw.”

“Ridiculous!”

“If you weren’t there,” said the policeman, “what are you doing, wearing that sailor-suit?”

The Bishop raised his eyebrows.

“I cannot permit my choice of costume,” he said, “arrived at—I need scarcely say—only after much reflection and meditation, to be criticized by a man who habitually goes about in public in a blue uniform and a helmet. What, may I inquire, is it that you object to in this sailor-suit? There is nothing wrong, I venture to believe, nothing degrading in a sailor-suit. Many of England’s greatest men have worn sailor-suits. Nelson—Admiral Beatty——”

“And Arthur Prince,” said Hypatia.

“And, as you say, Arthur Prince.”

The policeman was scowling darkly. As a dialectician, he seemed to be feeling he was outmatched. And yet, he appeared to be telling himself, there must be some answer even to the apparently unanswerable logic to which he had just been listening. To assist thought, he raised the glass of Buck-U-Uppo and seltzer in his hand, and drained it at a draught.

AND, as he did so, suddenly, abruptly, as breath fades from steel, the scowl passed from his face, and in its stead there appeared a smile of infinite kindliness and good-will. He wiped his moustache, and began to chuckle to himself, as at some diverting memory.

“Made me laugh, that did,” he said. “When old Booker went head over heels that time. Don’t know when I’ve seen a nicer punch. Clean, crisp—— Don’t suppose it travelled more than six inches, did it? I reckon you’ve done a bit of boxing in your time, sir.”

At the sight of the constable’s smiling face, the Bishop had relaxed the austerity of his demeanour. He no longer looked like Savonarola rebuking the sins of the people. He was his old genial self once more.

“Quite true, officer,” he said, beaming. “When I was a somewhat younger man than I am at present, I won the Curates’ Open Heavyweight Championship two years in succession. Some of the ancient skill still lingers, it would seem.”

The policeman chuckled again.

“I should say it does, sir. But,” he continued, a look of annoyance coming into his face, “what all the fuss was about is more than I can say. Our fat-headed Inspector says, ‘You go and raid that Home From Home, chaps, see?’ he says, and so we went and done it. But my heart wasn’t in it, no more was any of the other fellers’ hearts in it. What’s wrong with a little rational enjoyment? That’s what I say. What’s wrong with it?”

“Precisely, officer.”

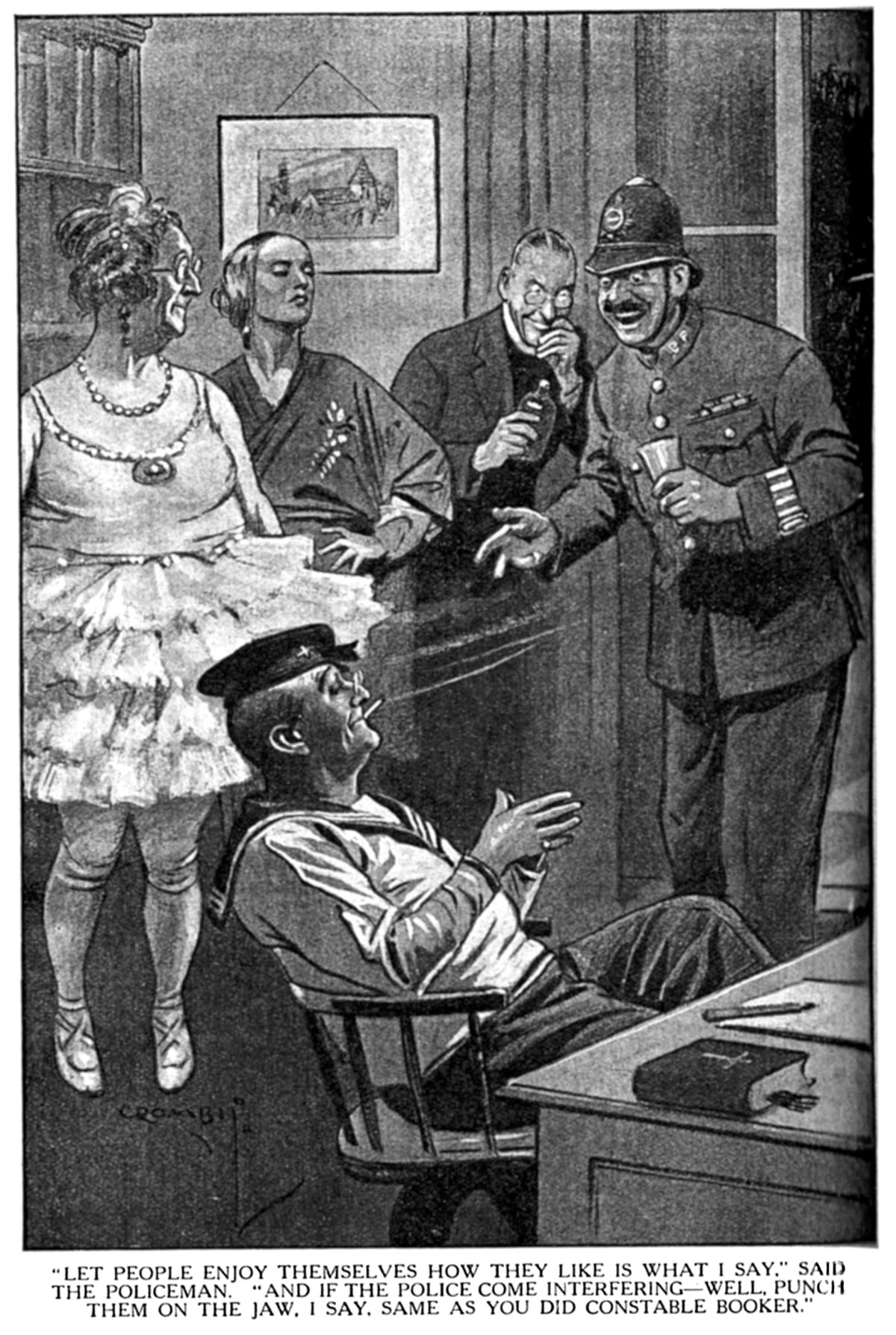

“That’s what I say. What’s wrong with it? Let people enjoy themselves how they like is what I say. And if the police come interfering—well, punch them on the jaw, I say, same as you did Constable Booker. That’s what I say.”

“Exactly,” said the Bishop. He turned to his wife. “A fellow of considerable intelligence, this, my dear.”

“I liked his face right from the beginning,” said the Lady Bishopess. “What is your name, officer?”

“Smith, lady. But call me Cyril.”

“Certainly,” said the Lady Bishopess. “It will be a pleasure to do so. I used to know some Smiths in Lincolnshire years ago, Cyril. I wonder if they were any relation?”

“Maybe, lady. It’s a small world.”

“Though, now I come to think of it, their name was Robinson.”

“Well, that’s life, lady, isn’t it?” said the policeman.

“That’s just about what it is, Cyril,” agreed the Bishop. “You never spoke a truer word.”

INTO this love-feast, which threatened to become more glutinous every moment, there cut the cold voice of Hypatia Wace.

“Well, I must say,” said Hypatia, “that you’re a nice lot!”

“Who’s a nice lot, lady?” asked the policeman.

“These two,” said Hypatia. “Are you married, officer?”

“No, lady. I’m just a solitary chip drifting on the river of life.”

“Well, anyway, I expect you know what it feels like to be in love.”

“Too true, lady.”

“Well, I’m in love with Mr. Bracy-Gascoigne. You’ve met him, probably. Wouldn’t you say he was a person of the highest character?”

“The whitest man I know, lady.”

“Well, I want to marry him, and my uncle and aunt here won’t let me, because they say he’s worldly. Just because he goes out dancing. And all the while they are dancing the soles of their shoes through. I don’t call it fair.”

She buried her face in her hands with a stifled sob. The Bishop and his wife looked at each other in blank astonishment.

“I don’t understand,” said the Bishop.

“Nor I,” said the Lady Bishopess. “My dear child, what is all this about our not consenting to your marriage with Mr. Bracy-Gascoigne? However did you get that idea into your head? Certainly, as far as I am concerned, you may marry Mr. Bracy-Gascoigne. And I think I speak for my dear husband?”

“Quite,” said the Bishop. “Most decidedly.”

Hypatia uttered a cry of joy.

“Good egg! May I really?”

“Certainly you may. You have no objection, Cyril?”

“None whatever, lady. I like to see the young folks happy.”

Hypatia’s face fell.

“Oh, dear!” she said.

“What’s the matter?”

“It just struck me that I’ve got to wait hours and hours before I can tell him. Just think of having to wait hours and hours!”

The Bishop laughed his jolly laugh.

“Why wait hours and hours, my dear? No time like the present.”

“But he’s gone to bed.”

“Well, rout him out,” said the Bishop, heartily. “Here is what I suggest that we should do. You and I and Priscilla—and you, Cyril?—will all go down to his house and stand under his window and shout.”

“Or throw gravel at the window,” suggested the Lady Bishopess.

“Certainly, my dear, if you prefer it.”

“And when he sticks his head out,” said the policeman, “how would it be to have the garden hose handy and squirt him? Cause a lot of fun and laughter, that would.”

“My dear Cyril,” said the Bishop, “you think of everything. I shall certainly use any influence I may possess with the authorities to have you promoted to a rank where your remarkable talents will have greater scope. Come, let us be going. You will accompany us, my dear Mulliner?”

Augustine shook his head.

“Sermon to write, Bish.”

“Just as you say, Mulliner. Then, if you will be so good as to leave this window open, my dear fellow, we shall be able to return to our beds, at the conclusion of our little errand of good-will, without disturbing the household staff.”

“Right-ho, Bish.”

“Then, for the present, pip-pip, Mulliner.”

“Toodle-oo, Bish,” said Augustine.

He took up his pen. Out in the sweet, scented night he could hear the four voices dying away in the distance. They seemed to be singing an old English part-song. He smiled benevolently.

“A merry heart doeth good like a medicine. Proverbs xvii., 22,” murmured Augustine.

He dipped pen in the ink, and resumed his composition.

This version of the story has one of the rare cases where Wodehouse’s text seems to have been changed to conform to an illustrator’s conception. In all other versions, the Bishop plugs Constable Booker in the eye. But Charles Crombie showed a punch to the jaw, and it was presumably easier to edit the text than to have the artist revise the illustration. See also the annotations to “Jeeves and the Song of Songs” for a change of the right to the left eye for similar reasons.

Compare the USA magazine version, also on this site.

Printer’s error corrected above:

Magazine, p. 540a, had an extraneous closing quotation mark after

said Hypatia.”

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums