A Prefect’s Uncle

by

P. G. Wodehouse

Literary and Cultural References

The following notes attempt to explain cultural, historical and literary allusions in Wodehouse’s text, to identify his sources, and to cross-reference similar references in the rest of the canon.

A Prefect’s Uncle was not serialized in magazines before its publication in London by A. & C. Black, 11 September 1903. It appeared in America the next month, bound by Macmillan from imported sheets.

These notes, by Neil Midkiff [NM] and others as credited below, are cross-linked with a transcription of the original edition; the return to text links will take you to the appropriate spot in the text transcription. In order to facilitate the back-and-forth views of text and notes, cross-reference links to other annotations or web pages are coded to open in a new browser tab; once finished with the cross-reference, just close that new tab and the return to text link will still be ready in these annotations. (If the cross-referenced note has a “return to text” link as well, do not use that; it will take you to the text of another book.)

The most common modern reprint is part of the Penguin paperback The Pothunters and Other School Stories, but its text differs slightly from the original edition, and these notes will not address those variants in general. Since our text transcription is not divided by pages, the following annotations do not have page numbers; the links back and forth with the text are intended to be more useful for readers here.

|

Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 Chapter 6 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 9 |

Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Chapter 12 Chapter 13 Chapter 14 Chapter 15 Chapter 16 Chapter 17 Chapter 18 |

Chapter I. Term Begins

I want a quiet word in season with the authorities

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

Wodehouse used “The Word in Season” as a story title in 1940 and 1958.

life is stern and life is earnest

An echo of Longfellow’s line “Life is real! Life is earnest!”

See Right Ho, Jeeves for the full poem.

the intellectual pressure of Marriott’s conversation

See A Damsel in Distress.

Gethryn was the head of Leicester’s

Gethryn was the senior student, with responsibility for maintaining order and discipline among the students in the house where Leicester was housemaster.

vice

Latin: in place of

school eleven

The school’s top cricket team, also called the first eleven.

His spirit was willing, but his will was not spirited.

See Biblia Wodehousiana for the Biblical phrasing of this familiar contrast.

The Powers that Be, however, were relying on Gethryn to effect some improvement.

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

the sixth

The Sixth Form, the senior class of students.

the first fifteen

The school’s top Rugby football team.

fives-courts

See The Pothunters.

je-ne-sais-quoi

French, literally “I don’t know what”; often referring to an indefinable quality of attraction or charm.

pure, undiluted cheek

Cheek is nineteenth-century British slang for impudence, audacity, disrespectful actions or attitude.

The Old Man

See The Pothunters.

the worst idiot on the face of this so-called world

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

gelatine-backboned

Wodehouse enjoyed this figure of speech and used variants of it throughout his career.

“Do you mean to say that you let your uncle order you about in a thing like this? Do you mean to say you’re such a—such a—such a gelatine-backboned worm——”

A Gentleman of Leisure/The Intrusions of Jimmy, ch. 17 (1910)

When I came in she looked at me in that darn critical way that always makes me feel as if I had gelatine where my spine ought to be.

“Extricating Young Gussie” (1915)

What a gelatin-backboned thing is man, who prides himself on his clear reason and becomes as wet blotting-paper at one glance from bright eyes!

Uneasy Money, ch. 20 (1916)

“If he’s such a gelatin-backboned worm that his mother can—”

The Little Warrior/Jill the Reckless, ch. 13.2 (1920/21)

That, Eunice had thought yearningly, as she talked to youths whose spines turned to gelatine at one glance from her bright eyes, was the sort of man she wanted to meet and never seemed to come across.

“The Rough Stuff” (1921; in The Clicking of Cuthbert, 1922)

Aunt Agatha always makes me feel as if I had gelatine where my spine ought to be.

“The Delayed Exit of Claude and Eustace” (1922; as ch. 16 in The Inimitable Jeeves, 1923)

“Worm!” said Jane. “Miserable, crawling, cringing, gelatine-backboned worm!”

“The Crime Wave at Blandings” (1936; in Lord Emsworth and Others, 1937)

And so compelling was her eye, and so menacing the way she was tapping her foot on the floor, that his spine turned to gelatine and he was about to throw in the towel and confess all, when there was a sound outside like a mighty rushing wind and in barged the baby’s Nanny.

“The Word in Season” (Punch, August 21, 1940)

The picture those words had conjured up had made him feel as if his spine had been suddenly removed and the vacancy filled with gelatine.

Spring Fever, ch. 10 (1948)

Bingo’s spine had turned to gelatine. It seemed useless to struggle further.

“The Word in Season” (in A Few Quick Ones, 1959)

your tour of moral agitation

Diego Seguí found this immediate source:

There is an evangelist now going about from church to church in the northern part of Illinois on a tour of moral agitation. His terms, as stated by himself, are “Forty dollars a week and fifty conversions guaranteed, or money refunded.” Converts are cheap in America. But nothing is said about permanent cures.

“By the Way” column in the Globe, September 11, 1902 (Wodehouse’s first full month on the column)

Wodehouse was undoubtedly quoting from The Belle of New York, an 1897/98 musical comedy (words by Hugh Morton, music by Gustave Kerker) which he mentions in Uneasy Money and other stories. The character Ichabod Bronson, president of the Young Men’s Rescue League and Anti-Cigarette Society, claims to be on a “tour of moral agitation” in that show; actually he is a wealthy hypocrite.

From far Cohoes, where the hop-vine grows,

And the youth of the town are prone to dissipation,

This faithful band, under my command,

Has embarked on a tour of moral agitation,

Without a pause, we shall spread our cause,

From the Hudson’s shore to the distant Bay of Biscay,

The world we’ll purge, of the deadly scourge,

Of the cold highball, and the cocktail made of whiskey,

For in the field of moral endeavor

No competitor can shake a stick at us.

First verse of Bronson’s song “The Anti-Cigarette Society”

fag

A junior student assigned to run errands and do minor chores for a senior student.

swot

One who studies especially hard in school, college, or military preparation; citations since 1850.

keeping wicket like an angel

Diego Seguí says this phrase is common in cricket reports, and suggests a parallel with a Biblical verse Wodehouse often references. In this analogy, batsman = Cherubim, bat = flaming sword, stumps = garden of Eden.

Genesis 3:24 / So he drove out the man: and he placed at the east of the garden of Eden Cherubims, and a flaming sword which turned every way, to keep the way of the tree of life.

the back of beyond

A very remote or out-of-the-way place; citations since 1816. Wodehouse used it as a haunted region in his light-hearted early ghost stories.

“Not,” he added with a snigger, “but what we do play practical jokes at the Back of Beyond.”

“A Joke and a Sequel” (1903)

“No. 704523186 Holborn was about the very wildest young spook that ever came across to the Back of Beyond.”

“The Reformed Humorist” (1903)

Sneg

The OED finds sneg, meaning snail, in glossaries of Kentish and Cornish slang from the 1880s.

What the dickens!

A euphemism for “What the devil!”; Shakespeare used it in The Merry Wives of Windsor.

serial stories which appear in papers destined at a moderate price to fill an obvious void, and which break off abruptly at the third chapter, owing to the premature decease of the said periodicals

This had happened to Wodehouse’s first novel The Pothunters; see the notes to our annotations for the story.

sovereign

A gold coin featuring the monarch’s image, valued at one pound sterling. Its purchasing power in modern terms (2025) is on the order of £150 or US$200.

“sheep or something out in Australia. Most uncles come from Australia.”

Wodehouse used the clichés of popular fiction readily, and one of these is the wealthy uncle from the Colonies.

“And the man always will choose Billy’s bowling to drop catches off. And Billy would cut his rich uncle from Australia if he kept on dropping them off him.”

Mike, ch. 17 (1907/09)

James’s Uncle Frederick was always talking more or less about the Colonies, having made a substantial fortune out in Western Australia, but it was only when James came down from Oxford that the thing became really menacing. … He had made his money keeping sheep.

“Out of School” (1910)

A compromise had been effected when his godfather, Mr. Sampson Broadhurst, arriving suddenly from Australia, had offered to take the young man back with him and teach him sheep-farming. It fortunately happening that he was a great reader of the type of novel in which everyone who goes to Australia automatically amasses a large fortune…

“The Awful Gladness of the Mater” (1925; in Mr. Mulliner Speaking, 1929/30)

“I’m your Uncle Percy from Australia, my boy. I married your late stepmother’s stepsister Alice.” [...] I don’t know if you have any pet day-dream, Corky, but mine had always been the sudden appearance of the rich uncle from Australia you read so much about in novels.

“Ukridge and the Old Stepper” (1928; in Eggs, Beans and Crumpets, 1940)

“He phoned me from the station an hour ago and said he’d had an unexpected legacy from his rich uncle in Australia and was leaving for New York right away.”

Laughing Gas, ch. 18 (1936)

And the wheel, which now appeared definitely to have accepted the role of Bingo’s rich uncle from Australia, fetched up another Black.

“All’s Well with Bingo” (1937; in Lord Emsworth and Others, 1937)

Architecturally, Walsingford Hall offended his cultured taste, but it had the same charm for him which a millionaire uncle from Australia exerts in spite of wearing a loud check suit and a fancy waistcoat.

Summer Moonshine, ch. 9 (1938)

The net result of all the various cases is that they will stick to about $20,000 and I shall get a refund of about $19,000, and the extraordinary thing is that instead of mourning over the lost $20,000 I am feeling frightfully rich, as if I had just been left $19,000 by an uncle in Australia.

Letter to Bill Townend dated April 12, 1947, in Performing Flea (1953)

“It turned out that she had recently been left a fortune by a wealthy uncle in Australia, and it had unseated her reason.”

Ring for Jeeves/The Return of Jeeves, ch. 7 (1953/54)

A wave of gratitude to my benefactor swept over me. I felt like a man who has suddenly discovered a rich uncle from Australia.

“Archie Had Magnetism” in America, I Like You (1956)

“Gosh!” he cried. “I feel as if a rich uncle in Australia had just handed in his dinner pail and left me a million sterling.”

“Joy Bells for Walter” (in A Few Quick Ones, 1959)

That was in those days roughly equivalent to £40 and £60, and to one whose highest prices for similar efforts had been at the most £10, the discovery that American editors were prepared to pay on such a scale was like finding a rich and affectionate uncle from Australia.

Introduction to Author! Author! (1962)

He looked like a fish that’s just learned that its rich uncle in Australia has pegged out and left it a packet.

Stiff Upper Lip, Jeeves, ch. 14 (1963)

brew

Prepare an afternoon meal of tea and other refreshments, such as the cake mentioned later.

the festive board

Usually, a dining table; here, whatever makeshift surface had held the tea and refreshments. See The Code of the Woosters for the Masonic origins of the term.

Chapter II. Introduces an Unusual Uncle

Chapter III. The Uncle Makes Himself at Home

Chapter IV. Pringle Makes a Sporting Offer

Chapter V. Farnie Gets into Trouble—

Chapter VI. —And Stays There

Chapter VII. The Bishop Goes for a Ride

Chapter VIII. The M.C.C. Match

Chapter IX. The Bishop Finishes His Ride

Chapter X. In Which a Case Is Fully Discussed

Chapter XI. Poetry and Stump-Cricket

Chapter XII. “We, the Undersigned”—

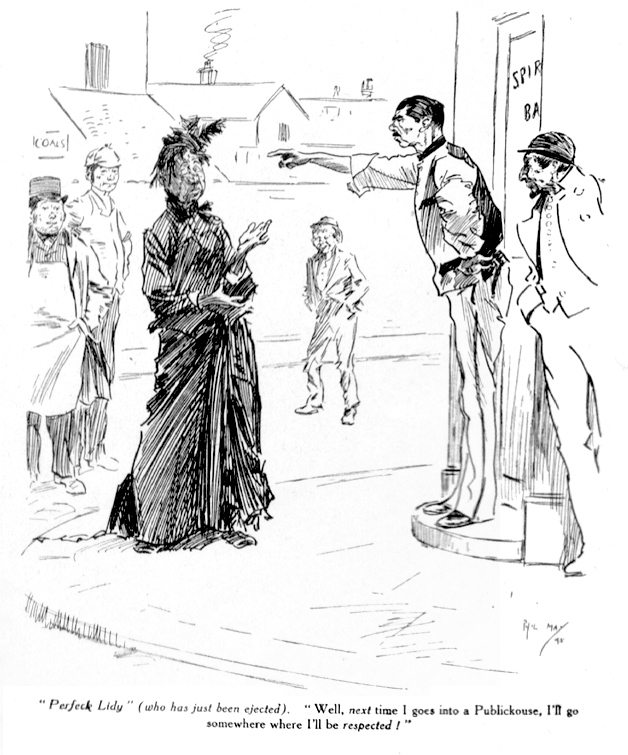

Like Mr Phil May’s lady when she was ejected (with perfect justice) by a barman, he went somewhere where he would be respected.

Diego Seguí found this in Punch, June 22, 1895. I found a few nostalgic references in books remembering this as one of Phil May’s most well-loved cartoons. Phil May (1864–1903) in his brief life helped transform the prevailing style of humorous drawings and caricatures from elaborate engravings to pen sketches whose economy of line conveyed character quickly to the viewer’s eye.

Chapter XIII. Leicester’s House Team Goes into a Second Edition

Chapter XIV. Norris Takes a Short Holiday

Chapter XV. Versus Charchester (at Charchester)

Chapter XVI. A Disputed Authorship

Chapter XVII. The Winter Term

Chapter XVIII. The Bishop Scores