The Story Thus Far:

HIS wealthy aunt—who had adopted him and educated him—having departed this life, leaving him a vast fortune, John Beresford Conway (commonly known as “Berry”) makes a painful discovery. The three or four tons of collateral so sweetly bequeathed him by Auntie is worthless!

Much grieved, but in need of ready cash, Berry gets a job—as secretary to a fussy old crab by the name of Frisby; T. Paterson Frisby, an American financier. Whereupon, he meets a friend of his affluent school days—Godfrey, Lord Biskerton, son and heir of the sixth Earl of Hoddesdon—and imparts the sad news to him.

His lordship (known to his intimates as “the Biscuit”) is properly shocked. Having finally recovered, however, he imparts a secret to Berry: He, too—the dashing Lord Biskerton—is suffering from a dearth of funds; likewise, his distinguished father and the Biscuit’s impressive aunt, Lady Vera Mace. In fact, Lady Vera is actually on the trail of a job!

To the Biscuit, Berry’s problem seems simple: Berry should permit the public to purchase some of Auntie’s investments. That stock in “The Dream Come True,” a defunct copper mine, for example—many would be pleased to get it! Why not get out of copper, and debt, at one and the same time? . . . Pondering his lordship’s suggestion, Berry goes to Mr. Frisby’s office. Mr. Frisby, it appears, has just received some most unpleasant news: his gay young niece, Ann Moon, of New York, will arrive shortly. Mr. Frisby must secure a chaperon for her at once—preferably a lady possessed of a title.

Just the job for Lady Vera! . . . Our hero telephones the glad tidings to the Biscuit. “I’ll have the old girl panting on the mat in half an hour!” says his lordship.

II

IF MR. FRISBY had been the sort of man who observes shades of emotion in his employees, he might have noticed in the demeanor of his private secretary at their recent encounter a certain unwonted gayety, a brightness that was almost effervescent. Berry’s was a buoyant temperament, easily stimulated by the passing daydream, and the more he had examined the Biscuit’s counsel, the better it looked to him. It amazed him that through all these years he had never once thought of raising a little money on the Dream Come True.

Certainly, the thing had never produced enough copper to make a door-knob, but, as the Biscuit had so wisely pointed out, the world was full of mugs. The daily papers proved their existence every morning. They were all over the place, now purchasing a gold brick from some sympathetic stranger, anon rushing to give another stranger all their available assets to hold so that they might show their confidence in him.

It would not be a bad idea, he reflected, to ask his employer’s advice on the matter. T. Paterson was, he knew, mixed up in Copper—he was president of Horned Toad, Inc.—and there were moments, in between his dyspeptic twinges, when he frequently became quite genial. It would be simple for a man of discernment to note the approach of one of these moments and put the necessary questions before the milk of human kindness ebbed again.

When he did find himself in Mr. Frisby’s presence again, however, it was to announce the arrival of Lady Vera Mace. The Biscuit’s aunt was not the woman to dally when there was money in the air. She arrived at three-thirty sharp.

“Lady Vera Mace is here, sir,” said Berry. “Shall I show her in?”

“Ugh.”

“And might I have a word with you later on a personal matter?”

“Ugh.”

Berry returned to his little room and resumed his daydreams. From time to time he wondered how the interview was coming along. He hoped that the Biscuit’s aunt was clicking. She needed the money, and she had once been kind to him as a schoolboy. Besides, the Biscuit would touch his commission, which would mean happiness all round.

She ought to get the job, he reflected. The passage of time, though it had prevented her recognizing him just now and resuming their ancient friendship, had been in other respects kind to Lady Vera Mace. She was still the rather formidably beautiful woman who had come down to the school years ago and stuffed him with food. Her voice was soft and silvery, her manner compelling. Unless he was greatly mistaken, she would rush T. Paterson off his feet and have him gasping for air in the first minute.

THE sound of the buzzer broke in on his meditations. Answering its summons, he found his employer alone. T. Paterson Frisby was leaning back in his swivel-chair, looking, as far as a great financier ever can do, rather fatuous. An unwonted smile was on his lips, and it was a foolish smile. Also, there was a rose in his buttonhole which had not been there before.

“Eh?” he said, starting, as Berry entered.

“Yes, sir?”

“What do you want?”

“What do you want, sir? You rang.”

Mr. Frisby seemed to come out of a trance.

“Oh! Yes. Take a note.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Pim’s. Friday.”

“Sir?”

“I’m giving Lady Vera Mace lunch at Pim’s on Friday,” translated Mr. Frisby. “She wants to see the Stock Exchange.”

“Yes, sir.”

“And those advertisements. Don’t put ’em in. Not needed.”

“No, sir.”

“I have arranged with Lady Vera that she will chaperon my niece when she arrives.”

“Yes, sir.”

Mr. Frisby seemed to return to his trancelike state. His eyes had half closed and he looked, though still pickled, almost human.

“That’s a remarkable woman,” he murmured. “She’s done my dyspepsia good.”

“Yes, sir?”

“She said it was mainly mental,” proceeded Mr. Frisby. He gave the impression of one soliloquizing with no thought of an audience. “She said drugs are no use. What one ought to do, she said, is think beautiful thoughts. Let sunshine into the soul, she said. She said, ‘Imagine that you are a little bird on a tree. What would you do? You would sing. So . . .’ ”

He broke off. The shock of imagining himself a little bird on a tree appeared to have roused him to a sense of his position.

“Well, she’s a very remarkable woman,” he said, almost defiantly. He blinked at Berry. “What was that you were saying just now? Something about wanting to see me about something? What is it?”

Berry embarked upon his recital with some confidence. His employer’s mood seemed to be admirably attuned to the giving of benevolent advice to his juniors. He had not seen him so gentle and amiable since the day Amalgamated Prunes had jumped twenty points at the opening of the market.

“It’s about a mine, sir. A mine in which I am interested.”

“What sort of mine?”

“A copper mine.”

MR. FRISBY’S geniality became frosted over with a thin covering of ice.

“Have you been taking a flyer in copper?” he asked dangerously. “Let me tell you here and now, young man, that I won’t have my office staff playing the market.”

Berry hastened to reassure him.

“I haven’t been speculating,” he said. “This mine is mine. A mine of my own. My mine. It belongs to me. I own it.”

“Don’t be a damned fool,” said Mr. Frisby severely. “How the devil can you own a mine?”

“My aunt left it to me.”

For the second time that day Berry sketched out his family history.

“Oh, I see,” said Mr. Frisby, enlightened. “Where is this mine?”

“Somewhere in Arizona.”

“What’s it called?”

“The Dream Come True,” said Berry uncomfortably. He was wishing that its original owner, in christening his property, had selected a name less reminiscent of a theme song.

“The Dream Come True?”

“Yes.”

Mr. Frisby sat forward in his chair and stared at his fountain-pen. He seemed to have fallen into a trance again.

“It has never produced any copper,” Berry went on in a rather apologetic voice. “But I was talking to a man at lunch, and he said that if one looked round one could always find someone to buy a mine.”

Mr. Frisby came to life.

“Eh?”

Berry repeated his remarks.

Mr. Frisby nodded.

“So you can,” he said, “if you pick the right sort of boob. And there’s one born every minute.”

“I was wondering if you could advise me as to the best way of setting about . . .”

“You say this mine has never yielded?”

“No.”

“Well, you can’t expect to get much for it, then.”

“I don’t,” said Berry.

Mr. Frisby took up his fountain-pen, gazed at it, and put it down again.

“Well, I’ll tell you,” he said. “Oddly enough, I know a man—Hoke’s his name, J. B. Hoke. He might make you an offer. He does quite a bit in that line. Buys up these derelict properties on the chance of some day striking something good. If you like, I’ll get in touch with him.”

“Thank you very much, sir.”

“I believe he’s in America just now. I’ll have to find out. Of course, he wouldn’t look at the thing unless he could get it cheap. Well, anyway, I’ll get in touch with him.”

“Thank you very much, sir.”

“You’re welcome,” said Mr. Frisby.

Berry withdrew. Mr. Frisby took up the receiver and called a number.

“Hoke?” he said. “Frisby speaking.”

“Yes, Mr. Frisby?” replied a voice, deferentially.

IT WAS a fat and gurgly voice. Hearing it, you would have conjectured that its owner had a red face and weighed a good deal more than he ought to have done.

“Want to see you, Hoke.”

“Yes, Mr. Frisby. Shall I come to your office?”

“No. Grosvenor House. About six.”

“Yes, Mr. Frisby.”

“Be on time.”

“Yes, Mr. Frisby.”

“Right. That’s all.”

“Yes, Mr. Frisby.”

People summoned by Mr. Frisby to interviews in his apartment at Grosvenor House always exhibited a decent humility. They seemed to indicate by their manner how clearly they realized that in this inner shrine they were standing on holy ground. The red-faced man who had entered the sitting-room at six precisely almost groveled.

J. B. Hoke was one of those needy persons who exist on the fringe of the magic world of finance and eke out a precarious livelihood by acting as “Hi, you!” and yes-men in ordinary to any of the great financiers who may wish to employ them. Willingness to oblige was Mr. Hoke’s outstanding quality. He would go anywhere you sent him and do anything you told him to do.

“Good evening, Mr. Frisby,” said J. B. Hoke. “How are you?”

“Never mind how I am,” said Mr. Frisby. “Got something I want you to do for me.”

“Yes, Mr. Frisby?”

“You know I’m president of the Horned Toad Copper Corporation?”

“Yes, Mr. Frisby.”

“Well, next door to it there’s a small claim called the Dream Come True. It’s been derelict for years.”

“Yes, Mr. Frisby?”

“I’ve had a letter from my directors. They seem to want to take it over for some reason. We’re putting in some developments on the Horned Toad and maybe they need the ground for workmen’s shacks or something. They didn’t say. I want you—”

“To trace the owner, Mr. Frisby?”

“Don’t interrupt,” said T. Paterson curtly. “I know the owner. The thing belongs to my secretary, a man named Conway. He was left it by someone, he tells me. I want you to go to him and buy it for me. Cheap.”

“Yes, Mr. Frisby.”

“I can’t appear in the matter myself. If young Conway thought that Horned Toad Copper was after his property, he’d stick his price up at once.”

“Yes, Mr. Frisby.”

“And there’s no hurry about buying it. I told him I would mention it to you, and I said you were in America. You don’t want to seem too eager. I’ll tell you when to shoot.”

“Yes, Mr. Frisby.”

“Right. That’s all.”

T. Paterson Frisby gave a Napoleonic nod, to indicate that the interview was concluded, and J. B. Hoke, just falling short of knocking his forehead on the floor, retired.

Having left the presence, Mr. Hoke went downstairs and turned into the passage leading to the American bar. A man who was sitting on a stool, sipping a cocktail, got up as he entered.

“Well?” he said.

He eyed Mr. Hoke woodenly. He was one of those excessively smoothly shaved men of uncertain age and expressionless features whom one associates at sight with the racing world. It was on a race course that J. B. Hoke had first made his acquaintance. His name was Kelly, and in the circles in which he moved he was known as Captain Kelly, though in what weird regiment of irregulars he had ever held a commission nobody knew.

He drew Mr. Hoke into a corner and once more inspected him with a wooden stare.

“What did he want?” he asked.

J. B. Hoke’s manner had undergone a change for the worse since leaving Mr. Frisby’s sitting-room. His gentle suavity had disappeared.

“The old devil,” he said disgustedly, “simply wanted me to act as his agent in buying up some derelict copper mine somewhere.”

He chewed a toothpick morosely, for Mr. Frisby’s summons had excited him and aroused hopes of large commissions. He had come away a disappointed man.

“What does he want with a derelict mine?” asked Captain Kelly, his fathomless eyes still fixed on his companion’s face.

“Says it’s next door to his Horned Toad,” grunted Mr. Hoke, “and they want the ground for putting up workmen’s shacks.”

“H’m!” said Captain Kelly.

“He didn’t need me. An office-boy could have done all he wanted. Wasting my time!” said J. B. Hoke.

CAPTAIN KELLY transferred his gaze to a fly which had alighted on his sleeve and was going through those calisthenics which flies perform on these occasions. One could gather nothing from his face, but from the fact that he had ceased to speak Mr. Hoke presumed that he was thinking.

“Well?” he said, not without a certain irritation. His friend’s inscrutability sometimes irked him.

The captain dismissed the fly with a jerk of the wrist.

“H’m!” he said again.

“What do you mean?”

“Sounds thin to me,” said the captain.

“What does?”

“What he says he wants that property for.”

“Seemed all right to me.”

“Ah, but you’re a fool,” the captain pointed out dispassionately. “If you want to know what I think, I’d say at a guess that a new reef of copper had been discovered.”

“Not on this claim,” said Mr. Hoke. “I happen to know the one he means. I was all over those parts a few years ago. I know this Dream Come True, which is its fool name. A fellow named Higginbottom, a prospector from Burr’s Crossing, staked it out a matter of ten years back. And from that day to this no one’s ever had an ounce of copper out of it. I shouldn’t say it had ever been worked after the first six months.”

“But they’ve been working the Horned Toad.”

“Of course they’ve been working the Horned Toad.”

“Suppose they had struck a vein and found that it went on into this property next door?”

“Chee!” said Mr. Hoke, his none-too-active brain stirring for the first time.

“I’ve heard of cases.”

“I’ve heard of cases,” said Mr. Hoke.

He stared at his companion emotionally. Rainbow visions had begun to rise before him.

“I believe you’re right,” he said. “That’s the way it looks to me.”

“There may be big money in this!”

“Ah!” said the captain.

“Now, see here . . .” said Mr. Hoke.

He lowered his voice cautiously and began to talk business. From time to time Captain Kelly nodded wooden approval.

AND so in due course, in the blue and apricot twilight of a perfect May evening, Ann Moon arrived in England with a hopeful heart and ten trunks and went to reside with Lady Vera Mace at her cozy little flat in Davies Street, Mayfair. And presently she was busily engaged in the enjoyment of all the numerous amenities which a London season has to offer.

She lunched at the Berkeley, tea-ed at Claridge’s, dined at the Embassy, supped at the Kit-Kat.

She went to the Cambridge May Week, the Buckingham Palace Garden Party, the Aldershot Tattoo, the Derby, and Hawthorn Hill.

She danced at the Mayfair, the Bat, Sovrani’s, the Café de Paris, and Bray’s on the River.

She spent week-ends at country houses in Bucks, Berks, Hants, Lincs, Wilts, and Devon.

She represented an Agate at a Jewel Ball, a Calceolaria at a Flower Ball, Mary Queen of Scots at a Ball of Famous Women Through the Ages.

She saw the Tower of London, Westminster Abbey, Madame Tussaud’s, Buck’s Club, the Cenotaph, Limehouse, Simpson’s in the Strand, a series of races between consumptive-looking greyhounds, another series of races between goggled men on motorcycles, and the penguins in St. James’s Park.

She met soldiers who talked of horses, sailors who talked of cocktails, poets who talked of publishers, painters who talked of sur-realism, absolute form and the difficulty of deciding whether to be architectural or rhythmical.

She met men who told her the only possible place in London to lunch, to dine, to dance, to buy an umbrella; women who told her the only possible place in London to go for a frock, a hat, a pair of shoes, a manicure and a permanent wave; young men with systems for winning money by backing second favorites; middle-aged men with systems that needed constant toning-up with gin and vermouth; old men who quavered compliments in her ear and wished their granddaughters were more like her.

And at an early point in her visit she met Godfrey, Lord Biskerton, and one Sunday morning was driven down by him in a borrowed two-seater to inspect the ancestral countryseat of his family, Edgeling Court, in the county of Sussex.

They took sandwiches and made a day of it.

THERE are those who maintain that the inhabitants of Great Britain are a cold, impassive race, not readily stirred to emotion, and that to get real sentiment you must cross the Atlantic. These would have solid support for their opinion in the sharply contrasting methods employed by the Courier-Intelligencer of Mangusset, Maine, and its older-established contemporary, the Morning Post of London, England, in announcing—some six weeks after the date on which this story began—the engagement of Ann Moon to Lord Biskerton.

Mangusset was the village where Ann’s parents had their summer home, and the editor of the Courier-Intelligencer, whose heart was in the right place and who had once seen Ann in a bathing suit, felt—justly—that something a little in the lyrical vein was called for. This, accordingly, was the way in which he hauled up his slacks—and he did it, which makes it all the more impressive, entirely on buttermilk. For, though the evidence seems all against it, he was a lifelong abstainer.

“The bride-to-be” (wrote ye Ed.) “is a girl of wondrous fascination and remarkable attractiveness, for with manner as enchanting as the wand of a siren and disposition as sweet as the odor of flowers and spirit as joyous as the caroling of birds and mind as brilliant as those glittering tresses that adorn the brow of winter and with heart as pure as dewdrops trembling in a coronet of violets, she will make the home of her husband a Paradise of enchantment like the lovely home of her girlhood, so that the heaven-toned harp of marriage, with its chords of love and devotion and fond endearments, will send forth as sweet strains of felicity as ever thrilled the senses with the rhythmic pulsing of ecstatic rapture.”

The Morning Post, in its quiet, hard-boiled way, confined itself to a mere recital of the facts. No fervor. No excitement. Not a tremor in its voice. It gave the thing out as unemotionally as on another page it had stated that the boys and girls of Birchington Road School, Crouch End, had won the championship and challenge cup for infant percussion bands at the North London Musical Festival held in Kentish Town.

Thus:

MARRIAGE ANNOUNCEMENTS

The engagement is announced between Lord Biskerton, son and heir of the Earl of Hoddesdon, and Ann Margaret, only child of Mr. and Mrs. Thomas L. Moon of New York City.

Sub-editors get that way in London. After a few years in Fleet Street they become temperamentally incapable of seeing any difference between a lot of infants tootling on trombones and a man and a maid starting out hand in hand on the long trail together. If you want to excite a sub-editor, you must be a Mystery Fiend and slay six with a hatchet.

But if the Morning Post was blasé, plenty of interest was aroused among the public that supports it. In a hundred beds a hundred young men stopped sipping a hundred cups of tea in order to give that notice their undivided attention. To some of these the paragraph had a sinister and an ominous ring. They concentrated their minds, such as they were, on the frightful predicament of the bridegroom-elect and, muttering to themselves “My God!” turned to the racing page with an uneasy feeling that nowadays no man was safe.

But there were others—and these formed a majority—who sank back on their pillows and stared wanly at the ceiling—silk pajama-clad souls in torment. They mused on the rottenness of everything, reflecting how rotten, if you came right down to it, everything was. They pushed aside the thin slice of bread-and-butter; and when their gentleman’s personal gentlemen entered babbling of spats, were brusque with them—in eleven cases telling them to go to the devil.

For these were the young men who had danced with Ann and dined with Ann and taken Ann to see the penguins in St. James’s Park and who, if they had happened to read the Mangusset Courier-Intelligencer, would have considered the editor a writer of bald and uninspired prose who did not even begin to get a grasp of his subject.

Ann Moon, in her progress through the London season, had undoubtedly made her presence felt. A girl cannot go about the place for a month and a half with a manner as enchanting as the wand of a siren without bruising a heart or two.

IN THE dining-room of The Nook, Mulberry Grove, Valley Fields, S. E. 21, Berry Conway came on the notice while skimming the paper preparatory to the morning dash for London on the 8:45. He was finding some difficulty in reading, owing to the activities of the Old Retainer, who had a habit of drifting in and out of the room during breakfast, issuing the while a sort of running bulletin of matters of local interest.

Mrs. Wisdom was plump and comfortable. She gazed at Berry with stolid affection, like a cow inspecting a turnip. To her, he was still the infant he had been when they had first met. Her manner toward him was always that of wise Age assisting helpless Youth through a perplexing world. She omitted no word or act that might smooth the path for him and shield him against life’s myriad dangers. In winter, she thrust unwanted hot-water bottles into his bed. In summer, she would speak freely, not mincing her words, of flannel next to the skin and of the wisdom of cooling off slowly when the pores had been opened.

“Major Flood-Smith,” said the Old Retainer, alluding to the retired warrior resident at Castlewood, next door but one, “was doing Swedish exercises in his garden early this morning.”

“Yes?”

“And the cat at Peacehaven had a sort of fit.”

Berry speculated absently on the mysteries of cause and effect.

“I hear Mr. Bolitho’s firm is sending him to Manchester. Muriel-at-Peacehaven told me. He wants to let Peacehaven furnished. I think he ought to put an advertisement in the papers.”

“Not a bad idea. Ingenious.”

Something in the passage attracted Mrs. Wisdom’s attention. She drifted out, and Berry heard umbrella-stands falling over. Presently she drifted in again.

“After the major had gone his niece came out and picked some flowers. A sweetly pretty girl, I always say she is.”

“Yes?”

“And what’s funny is, she was looking quite happy.”

“Why was that funny?”

“Why, Master Berry! Surely I told you about her? Her sad story?”

“I don’t think so,” said Berry, turning the pages. She probably had, he thought, but she told him so much local gossip—taking, as she did, a ghoulish relish in every disaster that happened to everybody in the suburb—that he had developed a protective deafness.

Mrs. Wisdom clasped her hands and threw up her eyes, the better to do justice to the big scoop.

“Well, really, I can’t imagine how I came not to tell you. I had it all from Gladys-at-Castlewood, and she got it partly by listening while waiting at table and the rest of it one evening when the young lady came down to the kitchen and wanted to know if the cook could make something she called fudge and then she stayed on herself and made this fudge, which seems to be a sort of soft toffee, and told them her sad story while stirring up the sugar and butter.”

“Ah?” said Berry.

“The young lady has come over from America. Her mother is the major’s sister, who married an American, and they live in a place near New York, which is called, though you can hardly believe it, Great Neck. Well, I mean, what a name to call a place. And Great Neck, it seems, Master Berry, is full of actors and the young lady her name is Katherine Valentine was foolish enough to think she had fallen in love with one of them and wanted to marry him and he wasn’t anybody really as he only acted small parts and her father of course was furious and he sent her over here to stay with the major in the hope that she might be cured of her infatuation.”

“Ah?” said Berry. “Good Lord! Look at this! The Biscuit has gone and jumped off the dock! Biskerton. Fellow I was at school with.”

“Committed suicide?” cried Mrs. Wisdom delightedly. “How dreadful!”

“WELL, not exactly suicide. He’s engaged to be married. To an American girl. Ann Margaret, only child of Mr. and Mrs. Thomas L. Moon of New York.”

“Moon?” Mrs. Wisdom wrinkled her forehead. “Now I wonder if that is the same young lady Gladys-at-Castlewood told me Miss Valentine told her about. Miss Valentine traveled over on the boat with a Miss Moon, and I feel sure Gladys told me that she told her that her name was Ann. They became great friends. Miss Valentine told Gladys that her Miss Moon was a very nice young lady. Very pretty and attractive.”

“The Morning Post doesn’t mention that. Still, if she’s pretty and attractive, I may be wronging the Biscuit in thinking he is selling himself for gold.”

“Why, Master Berry! What a thing to say of a friend of yours.”

“Well, it’s a bit of luck for him, anyway. I suppose this girl is rolling in money.”

“I hope you won’t ever marry for money, dear.”

“Not me. I’m romantic. I’m one of those fellows who are practically all soul.”

“I often say it’s love that makes the world go round.”

“I’ve never heard it put as well as that before,” said Berry, “but I shouldn’t wonder if you weren’t absolutely right. Was that the clock striking? I must rush.”

GEORGE, sixth Earl of Hoddesdon, father of the bridegroom-to-be, did not see his Morning Post till nearly eleven. He was a late riser and paper-reader. Having scanned the announcement with silent satisfaction, fingering at intervals the becoming gray mustache which adorned his upper lip, he put on a gray top hat and went round to see his sister, Lady Vera Mace.

“ ’Morning, Vera.”

“Good morning, George.”

“Well, I see it’s in.”

“The announcement? Oh, yes.”

Lord Hoddesdon eyed her reverently.

“How did you work it?” he asked.

“I?” His sister raised her eyebrows. “Work it?”

“Well, dash it,” said Lord Hoddesdon, who, like so many of England’s aristocracy, was prone to be a little unenthusiastic about his offspring, “don’t tell me that a girl like Ann Moon would accept a boy like Godfrey unless somebody had put in the deuce of a lot of preliminary spadework.”

“Naturally, I did my best to throw them together.”

“You would.”

“I told her as often as I could what a charming boy he was.”

“You said that!” exclaimed Lord Hoddesdon, incredulously.

“Well, so he is, when he likes to be. At any rate, he can be quite amusing.”

“He’s never made me so much as smile,” said Lord Hoddesdon. “Except once, when he tried to touch me for a tenner at Newmarket. Thank God he has found this girl.”

Once more he inflated the chest beneath his perfectly cut waistcoat. He sighed a sigh of exquisite contentment, and his handsome face glowed.

“It’ll be the first time the family has seen the color of real money,” he said, “since the reign of Charles the Second.”

There was a pause.

“George,” said Lady Vera.

“Hullo?”

“I want you to attend to me very carefully, George.”

Lord Hoddesdon surveyed his sister almost affectionately. He was seeing everything through rose-colored spectacles on this morning of mornings but, even making the necessary allowances for that, he was bound to admit that she looked extraordinarily attractive. Upon his word, felt Lord Hoddesdon, she seemed to get handsomer all the time. He made a mental calculation. Yes, well over forty, and anyone might take her for thirty-two. He was not at all sure that he liked the expression she was wearing at the moment. An odd expression. Rather hard.

“I want you to remember, George, that they are not married yet.”

“Of course. Naturally not. Announcement’s only just appeared in the paper.”

“AND so will you please,” proceeded Lady Vera, her beautiful eyes now definitely stony, “abandon your intention of calling on Mr. Frisby and asking him to oblige you with a small loan? It is just the sort of thing that might upset everything.”

Lord Hoddesdon gasped.

“You don’t imagine I would be fool enough to go touching Frisby?”

“Wasn’t that your idea?”

“Of course not. Certainly not. I was thinking . . . Er—I was wondering . . . Well, to tell you the truth, it crossed my mind that you might possibly be willing to part with a trifle.”

“It did, eh?”

“I don’t see why you shouldn’t,” said Lord Hoddesdon plaintively. “You must have plenty. There’s a lot of money in this chaperoning business. When you took on that Argentine girl three years ago, you got a couple of thousand pounds.”

“I got fifteen hundred,” corrected his sister. “In a moment of weakness—I can’t imagine what I was thinking of—I lent you the rest.”

“Er—well, yes,” said Lord Hoddesdon, not unembarrassed. “That is, in a measure, true. It comes back to me now.”

“It didn’t come back to me—ever,” said Lady Vera, in a voice that sounded, though not to her brother, like the tinkling of silver bells.

There was another pause.

“Oh, well, if you won’t, you won’t,” said Lord Hoddesdon gloomily.

“No,” agreed Lady Vera. “But I’ll tell you what I will do. I was going to take Ann to lunch at the Berkeley, but Mr. Frisby has rung up to ask me to motor down to Brighton for the day, so I will give you the money and you can look after her.”

Lord Hoddesdon felt a little like a tiger which has hoped for a cut off the joint and has been handed a cheese-straw, but he told himself with the splendid Hoddesdon philosophy that it was better than nothing.

“All right,” he said. “I’m not doing anything. Hand over the tenner.”

“The what?”

“Well, the fiver or whatever it may be.”

“Lunch at the Berkeley,” said Lady Vera, “costs eight shillings and sixpence. For two, seventeen shillings. Waiter, two shillings. Possibly Ann may like a lemonade or some water of some kind. Say two shillings again. Your hat-check sixpence. For coffee and unforeseen emergencies, half-a-crown. If I give you twenty-five shillings, that will be ample.”

“Ample?” said Lord Hoddesdon.

“Ample,” said Lady Vera.

Lord Hoddesdon fingered his mustache unhappily. He was feeling now as Elijah would have felt in the wilderness if the ravens had suddenly developed cutthroat business methods.

“But suppose the girl wants a cocktail?”

“She doesn’t drink cocktails.”

“Well, I do,” said Lord Hoddesdon mutinously.

“No, you don’t,” said Lady Vera, the note of hardness in her aspect now grown quite striking.

LORD BISKERTON was not a reader of the Morning Post. The first intimation he received that the announcement of his betrothal had appeared in print was when Berry Conway rang him up from Mr. Frisby’s office to congratulate him. He accepted his friend’s good wishes in a becoming spirit and resumed his breakfast in a quiet and orderly manner.

He was busy on the marmalade when his father arrived.

It was not often that Lord Hoddesdon visited his son and heir, but in some mysterious way there had floated into his lordship’s mind as he left Lady Vera’s flat the extraordinary idea that Biskerton might possibly have a little cash in hand and be willing to part with some of it to the author of his being.

“Er—Godfrey, my boy.”

“Hullo, guv’nor.”

Lord Hoddesdon coughed.

“Er—Godfrey,” he said, “I wonder . . . it so happens that I am a little short at the moment . . . I suppose you could not possibly . . .”

“Guv’nor,” said the Biscuit, amusedly, “this is Today’s Big Laugh. Don’t tell me you’ve come to make a touch?”

“I thought . . .”

“What on earth led you to suppose I’d got a bean?”

“I fancied that possibly Mr. Frisby might have made you some small present.”

“Why the dickens?”

“In celebration of the—er—happy event. After all, he is the uncle of your future bride. But, of course, if such is not the case . . .”

“Such,” the Biscuit assured him, “is decidedly not. The old moth-eaten fossil to whom you allude, guv’nor, is the one man in this great city who never makes small presents in celebration of any happy event. His family motto is Nil desperandum—Never give up.”

“Too bad,” sighed Lord Hoddesdon. “I was hoping that you would be able to help me out. I am sorely in need of monetary assistance. Your aunt has asked me to take your fiancée to lunch at the Berkeley this afternoon, and her idea of expense-money is little short of Aberdonian. Twenty-five shillings!”

“LAVISH,” said the Biscuit firmly. “I wish somebody would give me twenty-five bob. I’ve just a quid to see me through to the end of the month.”

“As bad as that?”

“One pound two and twopence, to be exact.”

“Still,” Lord Hoddesdon pointed out, “you must remember that your prospects are now of the brightest. You have been wiser in your generation than I in mine, my boy.” He stroked his mustache and heaved another regretful sigh. “As a young man,” he said, “my great fault was impulsiveness. I should have married money, as you are so sensibly doing. How clearly I see that now. And I had my opportunity—opportunity pressed down and running over.

“For months after I succeeded to the title wall-eyed heiresses were paraded before me in droves. But I was too romantic, too idealistic. Your poor mother was at that time a humble unit of the Gaiety Theatre company, and after I had been to see the piece in which she was performing sixteen times I suddenly noticed her. She was standing on the extreme O. P. side. Our eyes met . . . Not that I regret it for a moment, of course,” said Lord Hoddesdon. “As fine a pal as a man ever had. On the other hand . . . Yes, you have shown yourself a wiser man than your old father, my boy.”

Several times during this address the Biscuit had given evidence of a desire to interrupt. He now spoke forcefully.

“I wish you wouldn’t talk of Ann and wall-eyed heiresses without taking a long breath in between,” he said, justly annoyed. “When you say I’m marrying money, it makes it sound as if the cash was all I cared about. Let me tell you, guv’nor, that this is love. The real thing. I’m crazy about Ann. In fact, when I think that a girl can be such a ripper and at the same time be so dashed rich, it restores my faith in the Providence which looks after good men. She’s the sweetest thing on earth, and if I had more than one pound two and twopence I’d be taking her to lunch today myself.”

“A charming girl,” agreed Lord Hoddesdon. “How did you ever induce her to accept you?” he asked, a father’s natural bewilderment returning.

“It was Edgeling that did it.”

“Edgeling?”

“Edgeling. You may say what you like against our old ancestral seat, guv’nor—it costs a fortune to keep up and it’s too big to let and a white elephant generally, but there’s one thing about it—it’s romantic. I proposed to Ann in the old bowling-green—we had driven down in Pobby Blaythwaite’s two-seater—and it’s my belief there isn’t a girl in the world who could have held out in a setting like that. Doves were cooing, bees were buzzing, rooks were cawing, and the setting sun was gilding the ivied walls. No girl could have refused a fellow in such surroundings. Believe me, whatever its faults, Edgeling has done its bit and deserves credit.”

“And, talking of credit,” said Lord Hoddesdon, “it is pleasant to think that yours will now be excellent.”

The Biscuit laughed bitterly.

“Don’t you imagine it for an instant,” he said vehemently. He indicated a pile of papers on the table. “Look at those.”

“What are they?”

“Judgment summonses. If I hadn’t a good, level head, I’d be in the County Court tomorrow.”

Lord Hoddesdon uttered a startled cry.

“You don’t mean that!”

“I do. Those fellows are out for blood. Shylock was a beginner compared with them.”

“But, good God! Have you reflected? Do you realize? If you are taken into court, your engagement will be broken off. It is just the sort of thing that would appall a man like Frisby.”

The Biscuit held up a soothing hand.

“Have no fear, guv’nor. I have the situation well taped out. Trust me to take precautions. Look here.”

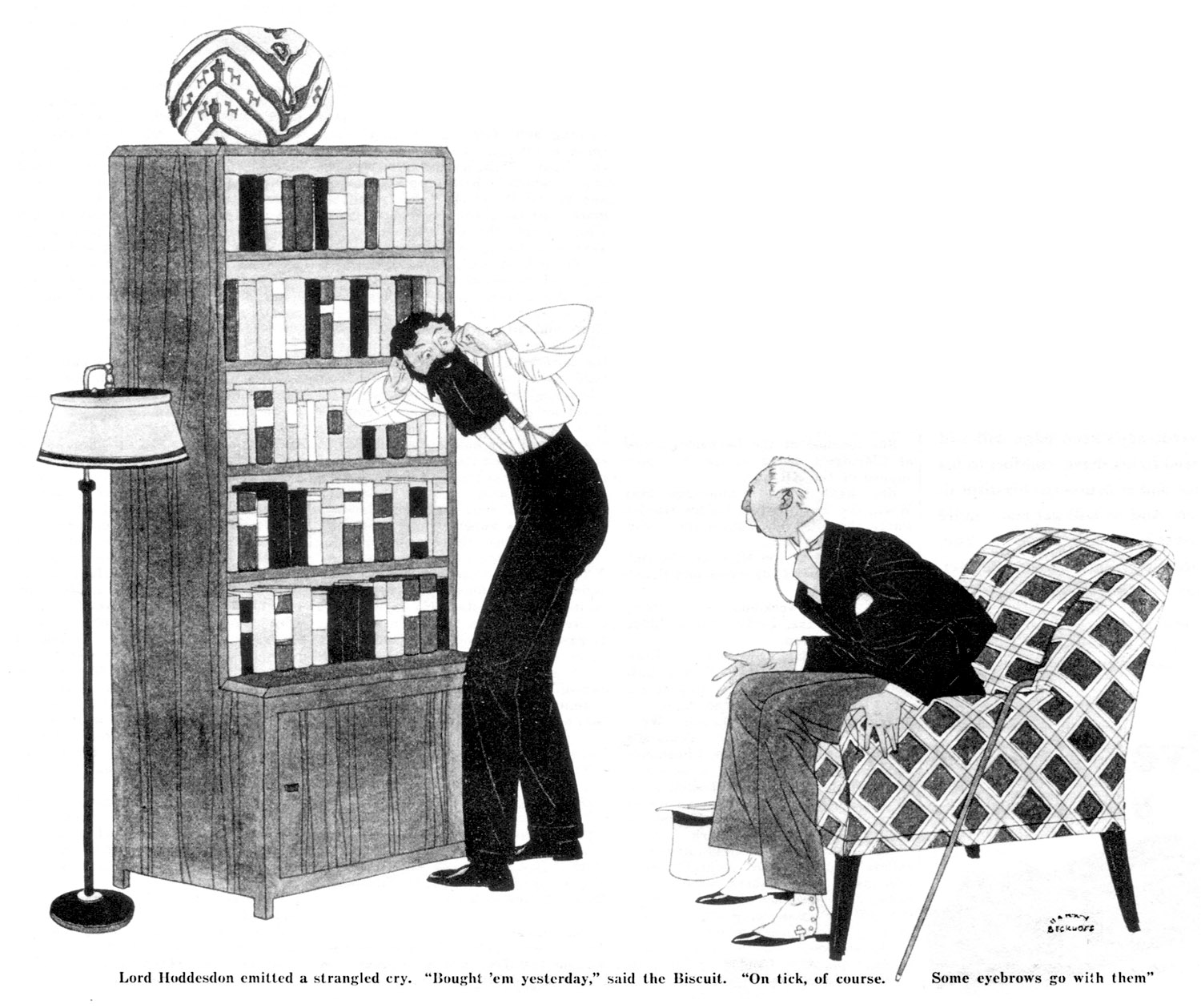

He went to a drawer, took something out, concealed himself for a swift instant behind the angle of the bookcase and emerged. And as he did so Lord Hoddesdon emitted a strangled cry.

HE MIGHT well do so. Except for the fact that he possessed his mother’s hair, Lord Biskerton’s appearance had never appealed strongly to the sixth Earl’s esthetic sense. And now, with a dark wig covering that hair and a black beard hiding his chin, he presented a picture so revolting that a father might be excused for making strange noises.

“Bought ’em at Clarkson’s yesterday,” said the Biscuit, regarding himself with satisfaction. “On tick, of course. Some eyebrows go with them. How about it?”

“Godfrey . . . my boy . . .” Lord Hoddesdon’s voice trembled, as a man’s will in moments of intense emotion. “You look terrible. Shocking. Ghastly. Like an international spy or something. Take the beastly things off!”

“But would you recognize me?” persisted his son. “That’s the point. If, say, you were Hawes and Dawes, Shirts, Ties and Linens, twenty-three pounds four and six, would you imagine for an instant that beneath this shrubbery Godfrey, Lord Biskerton, lay hid?”

“Of course I should.”

“I’ll bet you wouldn’t. No, not even if you were Dykes, Dykes and Pinweed, Bespoke Tailors and Breeches-Makers, eighty-eight pounds five and eleven. And I’ll tell you how I’ll prove it. You say you and Ann are lunching at the Berkeley. I’ll be there, too, at a table as near yours as I can manage. And if Ann lets out so much as a single ‘Heavens! It is my Godfrey!’ I’ll call a waiter, give him beard, wig and eyebrows, instruct him to have them fricasseed, and eat them.”

Lord Hoddesdon uttered a faint moan and shut his eyes.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums