The Story Thus Far:

T. PATERSON FRISBY, American financier residing in London, is owner of the Horned Toad, a copper mine. Having just learned that the adjoining mine—the Dream Come True—is worth millions, he is much surprised when his penniless secretary, young Berry Conway, calmly informs him that he, Berry Conway, is the owner, and, because the property is “obviously worthless,” wishes to sell it.

A great chance—for Mr. Frisby! He promptly sends the young man to a “possible purchaser”—one J. B. Hoke (a Frisby hireling), who, much to the disgust of one Captain Kelly who was to have been “in on” the deal and the estimable T. Paterson Frisby, buys the mine for himself.

Decidedly disgruntled, but still seeing golden possibilities, Frisby agrees to a merger of the two mines, and plans to clean up on the stock sale, to come later. . . .

Ann Moon, the charming American heiress and niece of Mr. Frisby, comes to London. Lady Vera Mace, aunt of “the Biscuit,” (known to the public as Godfrey, Lord Biskerton), gets the job of chaperoning her. Result: Ann and “the Biscuit” become engaged.

His lordship should be happy. He is not. His creditors are hounding him. How can he escape them—until marriage renders him solvent? Seeking advice, he goes to his dearest friend: none other than Berry Conway. “I’ll tell you what you do,” says Berry. “Change your name to Smith, leave London, and take a house near mine, at Valley Fields, until the storm’s over!”

Godfrey, Lord Biskerton, likes the suggestion, and acts on it. Whereupon, comfortably ensconced in the country, he meets a young neighbor—Miss Kitchie Valentine, American—proposes, and is accepted. . . . And Kitchie and Ann Moon are friends! . . .

Engaged to two girls! While he is wondering what to do, Berry Conway comes to him and tells him that he, Berry Conway, has met a most beautiful lady in London; to impress her he has told her he belongs to the secret service; they have become engaged; the name of the fair one is—Ann Moon. . . . Is his lordship shocked? He is not! . . . He and Berry discuss their problems: after which they learn something of The Dream Come True deal. Together, they evolve a plan to deal with the crooks. Then—

Berry resigns his position—and prepares to go after a fortune!

XI

TO BERRY CONWAY, hurrying across its verdant slopes to where the tea house nestled among shady trees, Hyde Park seemed to be looking its best and brightest. True, the usual regiment of loafers slumbered on the grass and there was scattered in his path the customary assortment of old paper bags; but this afternoon, such is the magic of love, these objects of the wayside struck him as merely picturesque. Dogs, to the number of twenty-seven, were barking madly in twenty-seven different keys; and their clamor sounded to him like music. If he had had time, he would have pursued and patted each separate dog and gone the rounds giving sixpences to each individual loafer. But time pressed, and he had to forego this piece of self-indulgence.

If anyone had told him that his manner during their recent chat had been of a kind to occasion Mr. Frisby pain, he would have been surprised and wounded. He was bubbling over with universal benevolence, and the five children who stopped him to ask the correct time received, in addition to the information, a sort of bonus in the form of a smile so dazzling that one of them, less hardy than the rest, burst into tears. And when, coming in view of the tea house, he perceived Ann already seated at one of the tables, his exhilaration bordered on delirium. The trees seemed to dance. The sparrows sang with a gayer note. The family at the next table, including though it did a small boy in spectacles and a velvet suit, looked like a beautiful picture. Many a person calmer than Berry Conway at that moment had been accepted—and with enthusiasm—by the authorities of hospitals as a first-class fever patient.

He leaped the railings and covered the remaining distance in two bounds.

“Hullo!” he said.

“Hullo,” said Ann.

“Here I am!” he said.

“Yes,” said Ann.

“Am I late?” asked Berry.

“No,” said Ann.

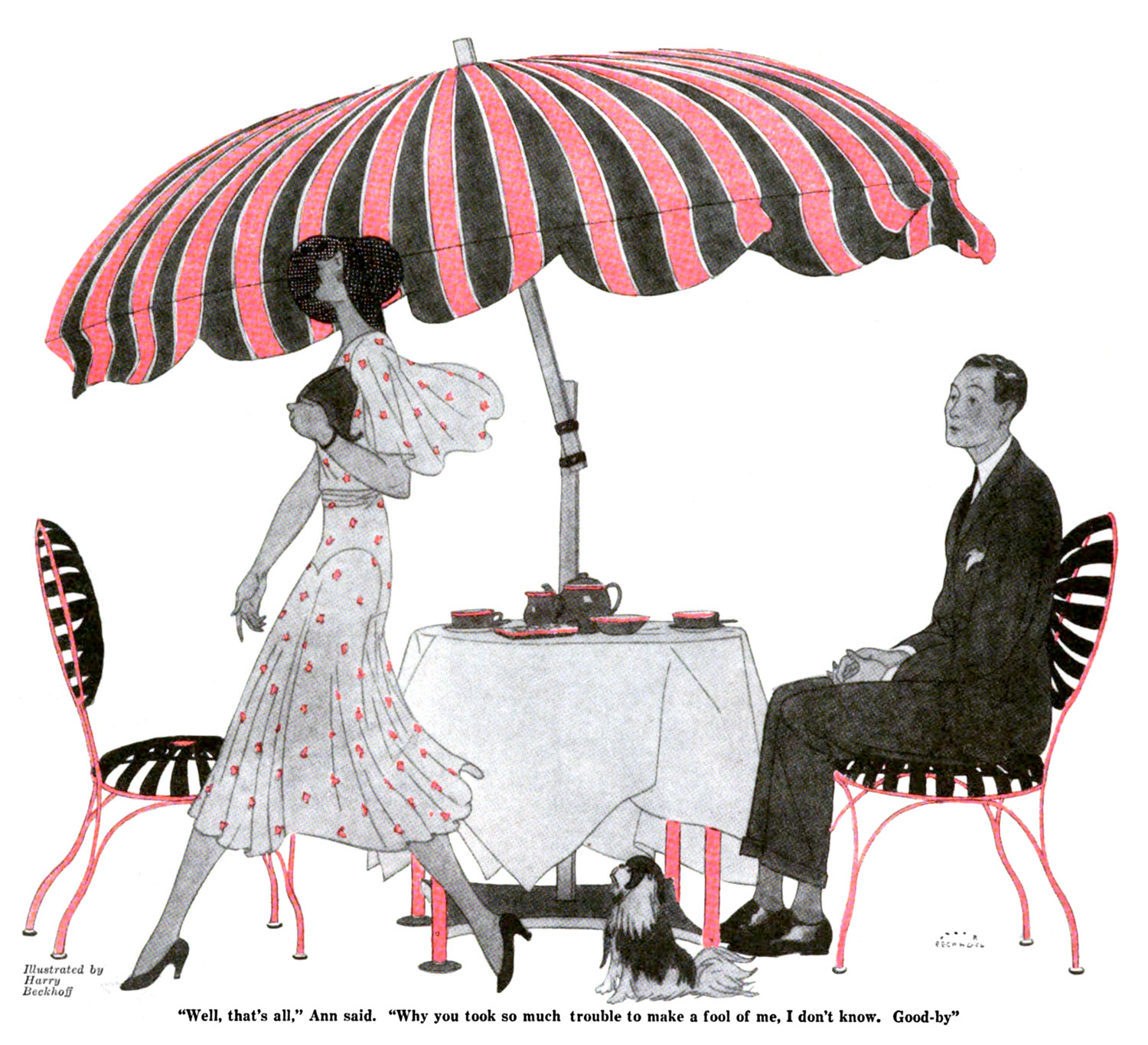

A JUST perceptible diminution of ecstasy came to Berry Conway. He felt ever so slightly chilled. Nearly eighteen long hours had passed since he and this girl had last met, and he could not help feeling that something more in the key of drama should have signalized their reunion. Of course, in a public place like Hyde Park girls are handicapped in the way of emotional expression. Had Ann sprung from her seat and kissed him, the small boy at the next table would undoubtedly have caused embarrassment by asking in a loud voice, “Ma-mah, why did she do that?” No, he could quite see why she did not spring and kiss him.

But—and now he saw what the trouble was—there was nothing whatever to prevent her smiling and—what is more—smiling with a shy, loving tenderness. And she had not done so. Her face was grave. If he had been in a slightly less exalted mood, he might have described it as unfriendly. There was not a smile in sight. Her mouth was set, and she was not looking at him. She was concentrating her gaze—letting her gaze run to waste, as it were—on a small, hard-boiled-looking Pekingese dog which had wandered up and was sitting by the table, waiting for food to appear.

Love sharpens the senses. Berry realized now what the matter was.

“I am late,” he said, contritely.

“Oh, no,” said Ann.

“I’m most frightfully sorry,” said Berry. “I had to see someone on my way here.”

“Oh?” said Ann.

Even a man with Berry’s rosy outlook could not blink the fact that the thermometer was falling. He cursed himself for not having been punctual. This, he told himself, was the way men rubbed the bloom off romance. They arranged to meet girls at five sharp at tea houses, and then they loitered and dallied and didn’t arrive till five-one or even five-two. And, meanwhile, the poor girls waited and waited and waited, like Marianas in Moated Granges, longing for their tea. . . .

Now he saw. Now he understood. Tea! Of course. All he had ever heard and read about the peril of keeping women waiting for their tea came back to him. And he was conscious of a great surge of relief. There was nothing personal about her coldness. It did not mean that she had been thinking things over and had decided that he was not the man for her. It simply meant that she wanted a spot of tea and wanted it quick.

He banged forcefully on the table.

“Tea,” he commanded. “For two. As quick as you can. And cakes and things.”

Ann had stooped, and was tickling the Peke. Berry decided for the moment, till the relief expedition should arrive with restoratives, to keep the conversation impersonal.

“Lovely day,” he said.

“Yes,” said Ann.

“Nice dog,” said Berry.

“Yes,” said Ann.

BERRY withdrew into a cautious silence. Talking only made him feel that he had been thrown into the society of a hostile stranger. He marveled at the puissance of this strange drug, tea, the lack of which can turn the sweetest girl into a sort of trapped creature that glares and snaps. Amazing to think that about two half-sips and a swallow would change Ann into the thing of gentleness and warmth that she had been last night.

He sat back in his chair, and tried to relieve the strain by looking at the silver waters of the Serpentine. From its brink a faint quacking could be heard. Ducks. In a very short while he and a restored, kindly Ann would be scattering bits of cake to those ducks. All that was needed now was . . .

“Ah!” said Berry.

A tray-laden waitress was approaching.

“Here comes the tea,” he said.

“Oh?” said Ann.

He watched her fill her cup. He watched her drink. Then, reassured, he braced himself to make his apology as an apology should be made.

“I feel simply awful,” he said, “about keeping you waiting like that.”

“I had only just arrived,” said Ann.

“I had to go and see someone. . . .”

“Who?”

“Oh, a man.”

Ann detached a piece of cake and dropped it before the Peke. The Peke sniffed at it disparagingly, and resumed its steady gaze. It wanted chicken. It is the simple creed of the Peke that, where two human beings are gathered together to eat, chicken must enter into the proceedings somewhere.

“I see,” said Ann. “A man? Not a gang?”

Berry started. The tea sprang from his cup. The words had been surprising enough, but not so surprising as the look which accompanied them. For, as she spoke, Ann had raised her head and for the first time her eyes met his squarely. And her eyes were like burning stones.

“Er—what?”

“A gang, I said,” replied Ann. Her eyes were daggers now. They pierced him through and through. “I thought that, whenever you had a spare five minutes, you spent it rounding up gangs.”

In the distance ducks were quacking. At the next table the small boy had swallowed a crumb the wrong way and was being pounded on the back by abusive parents. Sparrows twittered, and somewhere a voice was calling to Ernie to stop teasing Cyril. Berry heard none of these things. He heard only the beating of his heart, and it was like a drum playing the Dead March.

He opened his mouth to speak, but she stopped him.

“No, please don’t bother to tell me any more lies,” she said.

She leaned forward, and lowered her voice. What she had to say was not for the ears of the family at the next table.

“Shall I tell you,” she said, “how I spent the afternoon? When I got home last night, I had a talk with Lord Biskerton’s aunt, who is chaperoning me while I am over here. She had seen you and me dining at Mario’s, and she had a lot to say about it. I wanted to discuss things with you, so I went down to Valley Fields in my car, and called at The Nook. You were out, but there was an elderly woman there with whom I had quite a long chat.”

It seemed to Berry that he had uttered a sudden, sharp wail. But he had done so only in spirit. He sat there, staring silently before him, his whole soul in torment. She had met the Old Retainer! She had had quite a long chat with the Old Retainer! He shuddered at the thought of what she must have heard.

If ever there was a woman who could be relied on to spill the beans with a firm, unerring hand, that woman was the Old Retainer.

Ann continued speaking in the same low, even voice:

“SHE told me that you were the last person to do anything as nasty and dangerous as that, because you had always been so quiet and steady and respectable. She told me that you were my uncle’s secretary and had never done anything adventurous or exciting in your life. She told me that you wore flannel next your skin and bed socks in winter. And,” said Ann, “she told me that that scar on your temple was not caused by a bullet, but that you got it when you were six years old by falling against the hat stand in the hall because you forgot to scratch the soles of your new shoes.”

She rose abruptly.

“Well, that’s all,” she said. “Why you took so much trouble to make a fool of me, I don’t know. Good-by.”

She was walking away—walking out of his life; and still Berry found himself unable to move. Then, as she disappeared round the angle of the tea house, he seemed to come out of his trance. He sprang to his feet, and was hurrying after her to explain, to plead, to give her the old oil, to clear himself at least of the charge of wearing bed socks, when a voice arrested him:

“Jer want your bill, sir?”

It was the waitress, grim and suspicious. She disapproved of customers who developed a sudden activity before they had discharged their financial obligations.

“Oh!” Berry blinked. The waitress sniffed. “I was forgetting,” said Berry.

He found money, handed it over, waved away the change. But the delay, though brief, had been fatal.

He vaulted the railings and stood peering about him. Hyde Park basked in the summer sunshine, green and spacious. The dogs were there. The loafers were there. The paper bags were there. But Ann had gone.

The ducks in the Serpentine quacked on, unfed.

IN THE smoking-room of the low and seedy club which was his haunt Captain Kelly was listening with an expressionless face to an agitated Mr. Hoke.

“He said he knew your secret?”

“Yes.”

J. B. Hoke mopped his forehead. Emotion, coupled with the four double brandies which he had taken to restore himself after the shock of his recent interview with the Biscuit, had made him more soluble than ever. He had become virtually fluid.

“Which secret?” asked the captain.

“About the Dream Come True, of course.”

“Why of course? You must have a hundred, each shadier than the other.”

Mr. Hoke was not to be consoled by this kindly suggestion. He shook his head.

“This fellow’s a friend of young Conway. He lives next door to Conway. He was lunching with Conway. They were talking about the Dream Come True. Conway told me so. I thought right from the start that Conway had been listening at the door that day, and I was right.”

The captain considered.

“Maybe,” he said. “On the other hand, this red-headed chap may have been bluffing you.”

“I’m not so easy to bluff,” said Mr. Hoke, bridling despite his concern.

“No?” said Captain Kelly. He smiled a twisted smile. “Well, you were easy enough for me to bluff. You took in that story of mine about the gorillas without blinking. And you signed away half your cash on the strength of it.”

A hideous suspicion shot through Mr. Hoke. He trembled visibly.

“The gorillas?” he gasped. “Do you mean to say—?”

“Of course I do. Gorillas! There aren’t any gorillas. What would I be doing spending my money on gorillas? I made them up. It flashed into my mind. Just like that. You know how things flash.”

Mr. Hoke was breathing stertorously. It was as if this revelation of a friend’s duplicity had stunned him.

“And you fell for it,” said Captain Kelly, with relish. “I’d never have thought it of you. Going to cost you a lot, that is.”

Mr. Hoke recovered. He spoke venomously.

“Is it?” he said. “You think you’re onto a good thing, do you?”

“I know it.”

“Well, let me tell you something,” said Mr. Hoke. “Do you know how many shares of Horned Toad Copper I hold at the present moment?”

“How many?”

“Not one. Not a single solitary darned one. That’s how many.”

The captain’s face stiffened.

“What are you talking about?”

“I’ll tell you what I’m talking about. I sold all my holdings at four, and I was going to buy them back when I felt they’d gone low enough. And then we would have spilled the info’ about the new reef, and everything would have been fine. But now where are we? What is to prevent that red-headed young hound getting together some money and starting buying directly the market opens? What’s to prevent him buying up all the shares there are?”

Something of his companion’s concern was reflected on Captain Kelly’s face.

“H’m!” he said. He paused thoughtfully. “You really think he knows?”

“Of course he knows. He said ‘I know your secret.’ And I said ‘What secret?’ And he said, ‘Ah!’ And I said ‘About the Dream Come True?’ And he said, ‘That’s the one.’ ”

Captain Kelly eyed his friend unpleasantly.

“And you said you weren’t easy to bluff! I wish I’d been there.”

“What would you have done?”

“I’d have soaked you with a chair before you could start talking. Can’t you see he didn’t really know anything?”

“Well, he knows plenty now,” said Mr. Hoke sullenly. Recalling the scene, he sat amazed at his simplicity. He could not believe that it was he, J. B. Hoke, who had behaved like that. He put it down to the fact that those phantom gorillas had been preying on his mind to such an extent that he had become incapable of clear thought.

“What are you going to do about it?” asked Captain Kelly.

Mr. Hoke regarded him with cold reproach.

“What can I do about it?” he said. “I’ll tell you what I was going to do about it, if you like. I came here to ask you to send those two gorillas of yours down to Valley Fields, where this guy lives, and attend to him.”

“Cosh him?”

“THERE wouldn’t have been any need to cosh him. All that’s necessary is to keep Conway and that red-haired bird away from the market long enough to let me buy back that stock. They can’t do anything today, because the market’s closed. But, if they aren’t stopped, they’ll be there bright and early tomorrow morning. I was going to tell you to send these gorillas down to keep them bottled up at home till I was ready to let them out. They could have flashed a gun at them, and made them stay put. I only need a couple of hours tomorrow to clean up that stock. But what’s the use of talking about it now?” said Mr. Hoke disgustedly. “There aren’t any gorillas.”

He brooded disconsolately on this shortage. Captain Kelly was also brooding, but his thoughts had taken a different turn.

“It’s a good idea,” he said at length. “I wouldn’t have expected you to think of it.”

“What’s a good idea?”

“Bottling these fellows up.”

“Yeah?” said Mr. Hoke. “And how’s it going to be done?”

Captain Kelly smiled one of his infrequent smiles.

“We’ll do it.”

“Who’ll do it?”

“You and I’ll do it. We’ll go down there and do it tonight.”

Mr. Hoke stared. His potations had to a certain extent dulled his mental faculties, but he could still understand speech as plain as this.

“Me?” he said incredulously. “You think I’m going to horn into folks’ homes with a gat in my hand?”

“Ah,” said Captain Kelly.

“I won’t.”

“You will,” said the captain. “Or would you rather let these two chaps get away with it?”

Mr. Hoke quivered. The prospect was not a pleasant one.

“You’ve said yourself what will happen,” proceeded the captain, “if these fellows aren’t stopped. They’ll get hold of all that stock, and somebody will suspect something, and the price will go up, and when we try to buy we’ll have to pay through the nose.”

Mr. Hoke nodded pallidly.

“I remember M. T. O. Nickel opening at ten and going to a hundred and twelve two hours later on a rumor,” he said. “That was five years ago. It’ll be the same with Horned Toad. Once start fooling around with these stocks and you never know what won’t break.” He paused. “But go down to Valley Fields and wave gats!” he said, shaking gently like a jelly. “I can’t do it.”

“You’re going to do it,” said Captain Kelly firmly. “Have you got a gat?”

“Of course I haven’t got a gat.”

“Then go out and buy one now,” said Captain Kelly, “and meet me here at nine o’clock.”

CAPTAIN KELLY regarded Mr. Hoke censoriously. He did not like the way his friend had just tumbled into his car. Like a self-propelling sack of coals, the captain considered.

“Hoke,” he said, “You’re blotto!”

Mr. Hoke did not reply. He was gazing good-humoredly into the middle distance. His eyes were like the eyes of a fish not in the best of health.

“Oh, well,” said the captain resignedly. “Maybe the fresh air will do you good.”

He took his seat at the steering-wheel, and the car moved off. Nine o’clock struck from Big Ben.

“Got gat,” said Mr. Hoke, becoming chatty.

“Shut up,” said Captain Kelly.

Mr. Hoke laughed softly and nestled into his seat. The car slid on towards Sloane Square. Mr. Hoke nodded at the policeman on duty.

“Got gat,” he informed him as one old friend to another.

WHEN the poet Bunn (1790–1860) spoke of the heart being bowed down by weight of woe, he spoke, of course, as poets will, figuratively. Fortunately for the security of our public vehicles, grief has no tonnage. If the weight of human sorrow had been a thing of actual pounds and ounces, the Number Three omnibus which shortly before 8:30 p. m. set Lord Biskerton down at the corner of Croxleigh Road, Valley Fields, could never have made its trip from London. It must have faltered and stopped, and its wheels would have buckled under it. For the Biscuit was a heavy-hearted young man.

All through the long summer afternoon, starting about ten minutes after the conclusion of his interview with Mr. Hoke, his gloom had been deepening. And with reason.

“What,” J. B. Hoke had asked, in a fine passage, “is to prevent that red-headed young hound getting together some money and starting buying directly the market opens?”

The Biscuit could have informed him. The obstacle that stood between himself and anything in the nature of big buying in the market was the parsimony, the incredulity, the lack of broad vision displayed by his fellow human beings. Offered a vast fortune in return for open-handedness, they had declined to be open-handed. One and all, they had shrunk from entrusting him with the loan that would enable him to invade the market on the morrow and cash in on the private information he had received concerning the imminent boom in Horned Toad Copper.

When people saw Lord Biskerton coming, they automatically dipped into their note cases for fivers. They refused, to a man, to encourage him to go out of his class by giving him a thousand pounds, which was what he wanted now.

HE HAD tried prospects likely and unlikely. Dogged to the last, the fine old crusading spirit of the Biskertons had taken him even into the lair of the Messrs. Dykes, Dykes and Pinweed. And all Dykes, Dykes and Pinweed had done had been to babble nastily of their account. And finally, when young Oofy Simpson, notoriously the richest property at the Drones, had failed to develop pay ore, the Biscuit gave the thing up.

He made his way to Mulberry Grove with slow and dragging feet. His was a tortured soul. He writhed every time he thought of what he was missing.

Breathing heavily, the Biscuit reached Mulberry Grove and turned in at the gate of The Nook. He wanted sympathy, and Berry Conway could supply it. Hope, moreover, not yet quite dead, whispered that Berry might possibly be able to raise a bit of money. That bird Attwater . . . He had once lent Berry two hundred pounds, and Berry had paid it back. Surely this must have inspired Attwater with confidence. . . .

Becoming almost cheerful for a moment, the Biscuit tapped at the window of the sitting-room.

“Berry,” he called.

Berry was in, and he heard the tap. He also heard his friend’s voice. But he did not reply. He, too, was in the depths, and, much as he enjoyed the Biscuit’s society as a rule, he felt unequal to the task of chatting with him now. The Biscuit, he feared, would start rhapsodizing about his Kitchie, and every word would be a dagger in the heart. A man who has recently had his world shattered into a million fragments by a woman’s frown cannot lightly entertain happy lovers in his sitting-room.

So Berry crouched in the darkness, and made no sign. And the Biscuit, with a weary curse, turned away and sat on the front steps and smoked a cigarette.

Presently, finding no solace in nicotine, he rose and, going to the gate, leaned upon it. He surveyed the scene before him. Darkness was falling now, but the visibility was still good enough to enable him to perceive the swan Egbert floating on the ornamental water, and he speculated idly on the possibility of picking him off at this distance with a bit of stick. When the soul is bruised, relief can sometimes be found in annoying a swan. The Biscuit stooped and possessed himself of a sizable twig.

He was just poising this, trying to gauge the necessary trajectory, when between him and his objective there inserted itself a body. A tall, thin man of ripe years had come round the corner and was regarding him as if he had been the tombstone of a friend.

“Good evening, Mr. Conway,” said this person, in a sad voice that reminded the Biscuit of his bank manager regretting that in the circumstances it would be inconvenient—nay, impossible—to oblige him with the suggested overdraft. “This is Mr. Conway, I suppose? My name is Robbins.”

The error into which the senior partner of the legal firm of Robbins, Robbins, Robbins and Robbins had fallen was not an unnatural one. He had been dispatched by Mr. Frisby to Valley Fields to deal with an adventurer residing at The Nook, Mulberry Grove, and he had reached the gate of the Nook and here was a young man standing inside looking out. It is scarcely to be wondered at that Mr. Robbins considered that he had reached journey’s end.

“I should be glad of a word with you, Mr. Conway,” he said.

The interruption of his sporting plans annoyed the Biscuit.

“I’m not Mr. Conway,” he said, curtly. “Mr. Conway’s out.”

Mr. Robbins held up a gloved hand. He had expected this sort of thing.

“Please!” he said. “I can readily imagine that you would prefer to avoid a discussion of your affairs, but I fear I must insist.”

Mr. Robbins had two manners—both melancholy but each quite distinct. When having a friendly talk with a client on a matter of replevin or the like, he allowed himself to ramble. When dealing with adventurers, he was crisp.

He spoke coldly, for he disliked the scoundrel before him:

“I represent Mr. Frisby, with whose niece, I understand, you are proposing to contract an alliance. My client is fully resolved that this marriage shall not take place, and I may say that you will gain nothing by opposing his wishes. An attitude of obduracy and defiance on your part will simply mean that you lose everything. Be reasonable, however, and my client is prepared to be generous. I think you will agree with me, Mr. Conway—here in camera, as one might say, and with no witnesses present—that heroics are unnecessary and that the only aspect of the matter on which we need touch is the money aspect.”

THE Biscuit had not allowed this address to be delivered without attempted punctuation. He had had far too much to put up with that afternoon to be willing to listen meekly to gibberers. The other’s white hairs, just visible under his top hat, protected him from actual assault, or he would have squashed that top hat in with a single blow of the fist. However, he had endeavored to speak, only to find the practiced orator riding over him and taking him in his stride. Now that his companion had paused, and he had an excellent opportunity of reiterating that a mistake had been made, he did not seize it. The thought that at the eleventh hour Fate had sent him a man who talked about money—vaguely at present, but nevertheless with a sort of golden promise in his voice—held him dumb.

“Come now, Mr. Conway,” said Mr. Robbins. “Are we going to be sensible?”

The Biscuit choked. The twig dropped from his nerveless hand.

“Are you offering me money to . . .”

“Please!”

“Let’s get this straight,” said the Biscuit. “Is there or is there not money on the horizon?”

“There is. I am empowered to offer . . .”

“How much?”

“Two thousand pounds.”

Mulberry Grove swam before the Biscuit’s eyes. The swan Egbert looked like two swans, twin brothers.

“Yes, think it over,” said Mr. Robbins.

He adjusted his coat, draping it about him so as more closely to resemble a winding-sheet. The Biscuit leaned on the gate in silence.

“When do I get it?” asked the Biscuit at length.

“Now.”

“Now?”

“I have a check with me. See!” said Mr. Robbins, pulling it out and dangling it.

He had no need to dangle long.

“Gimme!” said the Biscuit hoarsely, and snatched it from his grasp.

Mr. Robbins regarded him with a sorrowful loathing. He had expected acquiescence, but not acquiescence quite so rapid as this. Despite the fact that he had stressed his disinclination for heroics, he had not supposed that this deal would have been concluded without at least an attempt on this young villain’s part to affect reluctance.

“I think I may congratulate the young lady on a fortunate escape,” he said, icily.

“Eh?” said the Biscuit.

“I say I may congratulate . . .”

“Oh, ah,” said the Biscuit. “Yes. Thanks very much.”

Mr. Robbins gave up the attempt to pierce this armored hide.

“Here is my card,” he said, revolted. “You will come to my office tomorrow and sign a letter which I shall dictate. I wish you good evening, Mr. Conway.”

“Eh?” said the Biscuit.

“Good evening, Mr. Conway.”

“What?” said the Biscuit.

“Oh, good night,” said Mr. Robbins. He turned, and walked away. His very back expressed his abhorrence.

The Biscuit stood for a while gaping at the ornamental water. Then, walking slowly and dazedly to Peacehaven, he mixed himself the whisky-and-soda which the situation seemed to him so unquestionably to call for.

In the intervals of imbibing it, he sang joyously in a discordant but powerful baritone. The wall separating the sitting-room of Peacehaven from the sitting-room of The Nook was composed of one thickness of lath and plaster, and Berry Conway, wrestling with his tragedy, heard every note.

He shuddered. If that was how love was making his neighbor feel, he was glad that he had been firm and had paid no attention to his knocking on the window.

IT WAS some twenty minutes later that the car containing Captain Kelly and his ally, Mr. Hoke, turned into Mulberry Grove.

“Here we are,” said the captain. “Get out.”

Mr. Hoke got out.

“Now,” said Captain Kelly, having, in his military fashion, surveyed the terrain, “this is what we do, so listen, you poor sozzled fish. You go round to the back and stay there. I’ll stick here, in the front. And, remember, no one is to leave either of those two houses. And, if anyone goes in, they’ve damn’ well got to stay there. Do you understand?”

Mr. Hoke nodded eleven times with sunny good will.

“Got gat,” he said.

A diet of large whiskies and small sodas, persisted in through the whole of a long afternoon and evening, and augmented by an occasional neat brandy, is a thing which cuts, as it were, both ways. It had had the effect of bringing J. B. Hoke to the back garden of The Nook with a revolver in his hand—a feat which he could never have achieved purely on lemonade; and so far it may have been said to have answered its purpose. But it had also had the effect of blurring Mr. Hoke’s faculties.

Instinctively feeling that it would be sure to come in useful, J. B. Hoke had provided himself for this expedition with a large pocket flask. He now produced this, and drank deeply of its contents. And his mood, which had begun by being one of amiable vacuity and had changed to one of self-pity, changed again. If somebody had come along and flashed a light on Mr. Hoke’s face at this moment, he would have perceived on it an expression of sternness. He was thinking hard thoughts of Berry and his friend. Trying to sneak out and slip something across a good man, were they? Ha! thought Mr. Hoke.

WITH a wide and sweeping gesture, designed to indicate his contempt for and defiance of all such petty-minded plotters, he flung an arm dramatically skywards. Unfortunately, it was the arm which ended in the hand which ended in the fingers which held the flask; and the fingers, unequal to the sudden strain, relaxed their grip. The next moment the precious object had vanished into the night, with its late owner in agonized pursuit.

Mr. Hoke had never been a reader of poetry. Had he been, those poignant words of Longfellow:

I shot a flask into the air:

It fell to earth, I knew not where,

would undoubtedly have flashed into his mind, for they covered the situation exactly. The night was dark, and the grounds of The Nook, though not large compared with places like Blenheim or Knole, were quite large enough to hide a flask. For many long and weary minutes Mr. Hoke traversed them from side to side and from end to end like a hunting-dog. He poked in bushes. He went down on his hands and knees. He scrutinized flower beds. But all to no avail.

J. B. Hoke gave it up. He was beaten. Sadly he rose from the last flower bed; and, turning, was aware that there was light in one of the ground-floor windows, where before no light had been. Interested by this phenomenon, he hurried across the lawn and looked in.

The young man, Conway, was there, eating cold ham and drinking whisky.

The discovery that he was on the point of perishing of thirst and hunger had come quite suddenly to Berry as he sat nursing his sorrow in the darkened sitting-room. At first he had repelled it, for the mere thought of taking nourishment was, in his present frame of mind, odious to him. Then, as the urge grew greater, he had succumbed. He had gone to the larder and foraged. And now he was setting to with something like enthusiasm.

Mr. Hoke, crouching outside the window, eyed him wistfully. He could have done with a slice of that ham. He could have used that whisky. He flattened his nose against the pane and stared wolfishly. A yearning for his lost flask tormented him.

Suddenly he observed the banqueter stiffen in his chair and raise his head, listening. Mr. Hoke had heard nothing, and was not aware that the front door bell had rung. But Berry had heard it, and a wild, reasonless hope shot through him that it was Ann, come to tell him that in spite of all she loved him still. True, she had given at their parting no indication of the likelihood of any such change of heart, but the possibility was enough to send Berry shooting out of the door and down the hall. Mr. Hoke found himself looking into an empty room.

Empty, that is to say, except for the ham on the table and the whisky bottle beside it. These remained, and J. B. Hoke found in their aspect something magnetic, something that drew him like a spell. He tested the window. It was not bolted. He pushed it up. He climbed in. What with the tumult of his thoughts and the necessity of drinking his courage to the sticking-point, Mr. Hoke tonight had for perhaps the first time in his life omitted to dine, preferring to concentrate his energies on the absorption of double whiskies. He was now ravenously hungry, and he assailed the ham with a will. He also helped himself freely from the whisky bottle.

A MAN who is already nearly full to the top with mixed spirits cannot do this sort of thing without experiencing some sort of spiritual change. At the beginning of the meal J. B. Hoke had been morose and particularly unkindly disposed towards Berry. By the time he had finished a gentler mood prevailed. He was feeling extraordinarily dizzy, but with the dizziness had come a strongly marked benevolence and a keen desire for the society of his fellows.

He rose. He went to the door. From the direction of the sitting-room came the buzz of voices. Evidently some sort of social gathering was in progress there, and he wanted to be in it.

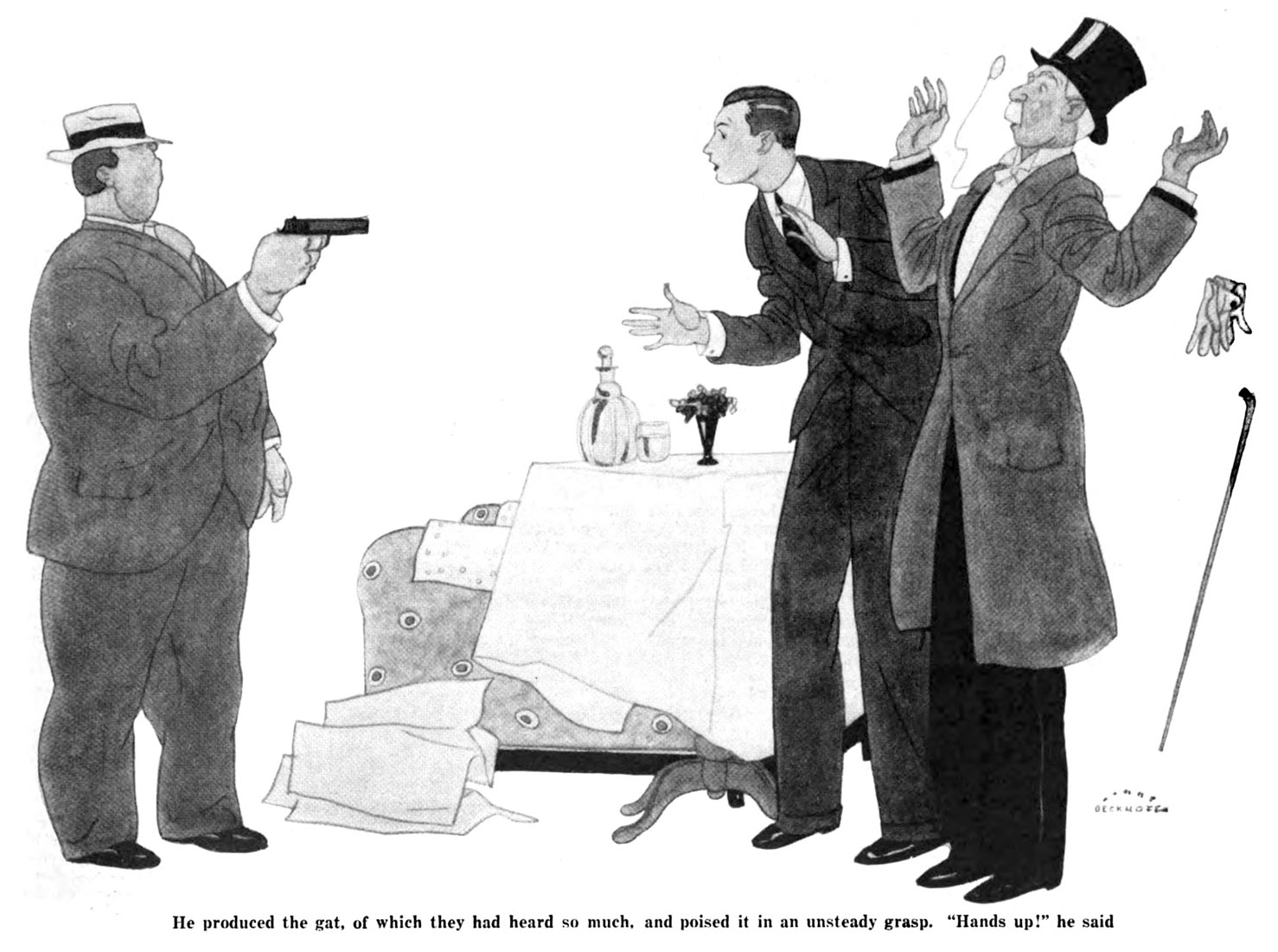

He zigzagged down the passage, chose after some hesitation the middle one of the three handles with which a liberal-minded architect had equipped the sitting-room door, and, walking in, gazed on the occupants with a smile of singular breadth and sweetness.

There were two persons present. One was Berry. The other was a distinguished-looking man of middle life with a clean-cut face and a gray mustache. Both seemed surprised to see him.

“ ’Lo!” said Mr. Hoke, spaciously.

Berry, in his capacity of host, answered him.

“Hullo!” said Berry. The apparition had not unnaturally startled him somewhat. “Mr. Hoke!”

“Hic-coke,” replied Hoke, endorsing the statement.

Berry had now arrived at a theory which seemed to him to cover the facts. He assumed that after admitting Lord Hoddesdon a short while back he had forgotten to close the front door, and that his latest visitor, finding it open, had come in. It was a thing that might quite easily have happened, for his lordship’s arrival, puzzling him completely, had taken his mind off all other matters. At any rate, here Hoke was, and he endeavored politely to discover what had brought him there.

“Do you want to see me about something?” he asked.

“Got gat,” said Mr. Hoke pleasantly.

“Cat?” said Berry.

“Gat,” said Mr. Hoke.

“What cat?” asked Berry, still unequal to the intellectual pressure of the conversation.

“Gat,” said Mr. Hoke with an air of finality.

Berry tentatively approached the subject from another angle.

“Hat?” he said.

“Gat,” said Mr. Hoke.

He frowned slightly, and his smile lost something of its effervescent bonhomie. This juggling with words was giving him a slight, but distinct, headache.

Lord Hoddesdon, too, seemed far from genial. The interruption, coming at a moment when he had begun to talk really well, annoyed him.

Considering that he had stated so firmly and uncompromisingly to his sister Vera that nothing would induce him ever to return to Valley Fields, the presence of Lord Hoddesdon in Berry’s sitting-room requires, perhaps, a brief explanation. Briefly, he had changed his mind. It is the distinguishing mark of a great man that he is never afraid to change his mind, should he see good reason to do so. And Lord Hoddesdon, thinking things over in his club, had seen excellent reason.

Lady Vera’s revelations on the previous night had shaken him to the core. If Ann Moon was really planning to jilt his son and marry this Conway, the matter was serious. Although nothing in the millionaire’s behavior so far had indicated a desire to part with money, it had seemed to Lord Hoddesdon, always an optimist, that, once the girl was married to his son, he would surely be in a position to work Mr. Frisby for a small loan. He and T. Paterson would then, dash it, be practically relations. It was vital, accordingly, that this Conway be firmly suppressed by one in authority.

Conscious, therefore, of the fact that he now had six hundred pounds in his account at the bank, he had come to The Nook to buy the fellow off. He had come by night, because in his opinion Valley Fields was safer then. And he had just been in the act of talking to him as a head of the family should have talked, when this disgusting interruption had occurred. Right in the middle of one of his best sentences the door had opened and in had staggered a large, red-faced inebriate.

CONSCIOUS that the spell had been broken and that further discussion of a delicate matter must be postponed, and feeling bitterly that this was just the sort of friend he might have expected the man Conway to have, Lord Hoddesdon rose.

“Where is my hat?” he said stiffly.

“Gat,” said Mr. Hoke, his annoyance increasing. It seemed to him that these people were deliberately affecting to misunderstand plain English.

He regarded Lord Hoddesdon, now making obvious preparations for departure, with a hostile eye. For some little time he had been allowing his mind to wander from his mission, but now Captain Kelly’s words came back to him. “No one is to leave either of these houses,” the captain had said. “And, if anyone goes in, they’ve damn’ well got to stay there.” This gray-mustached stiff had gone in. Very well. Now he would stay here.

“You thinking of leaving?” asked Mr. Hoke.

Lord Hoddesdon raised his eyebrows. Impecuniosity and the exigencies of a democratic age had combined to cause his lordship to be sparing of the hauteur which so often goes with blue blood; but he employed it now. He stared at J. B. Hoke like a seigneur of the old régime having a good look at a vassal or varlet.

‘ ‘I haven’t the pleasure of knowing who you are, sir. . . .”

Berry did the honors.

“Mr. Hoke . . . the Earl of Hoddesdon. . . ”

Mr. Hoke’s severity waned a little.

“Are you an oil?” he said, interested.

“. . . But, in answer to your question, I am thinking of leaving,” said Lord Hoddesdon.

Mr. Hoke’s momentary lapse into amiability was over.

“Oh, no!” he said.

“I beg your pardon?” said Lord Hoddesdon.

“Granted,” said Mr. Hoke. He produced the gat, of which they had heard so much, and poised it in an unsteady but resolute grasp. “Hands up!” he said.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums