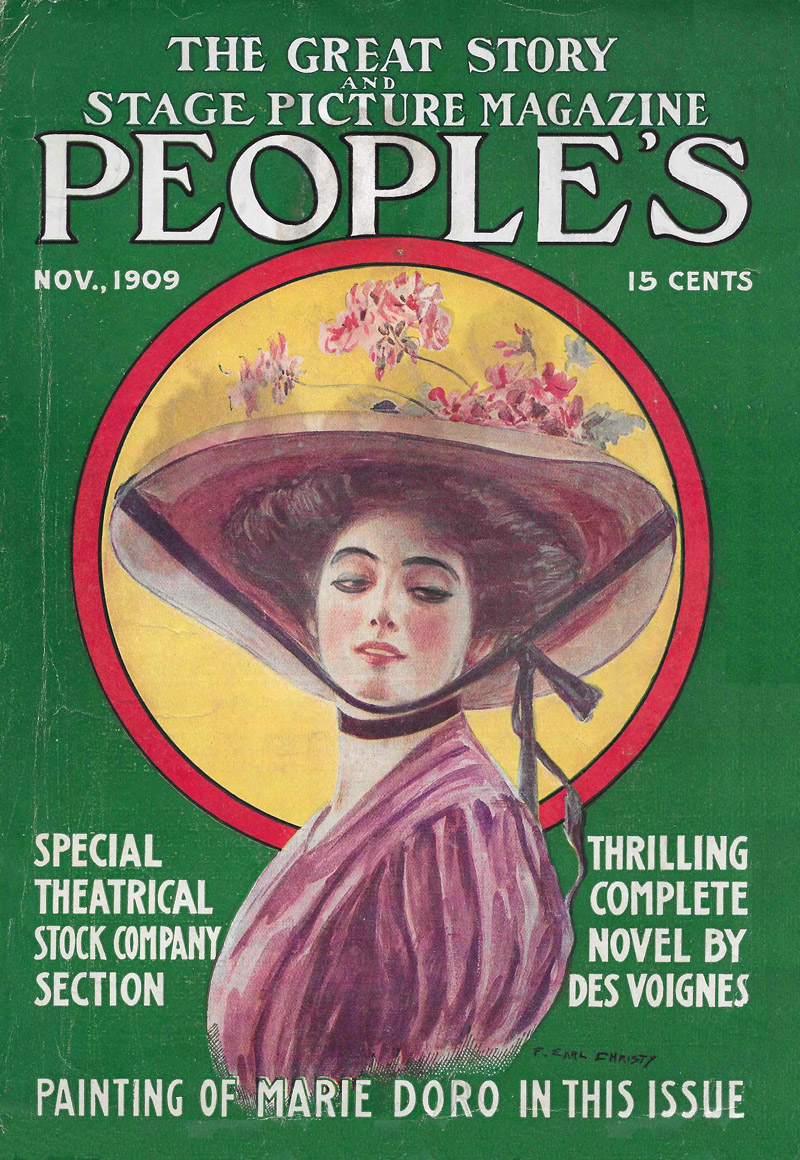

People’s Magazine, November 1909

BOUT Alcala, as about many other of New York’s apartment houses, there is something a little pathetic. It resembles a decayed gentleman struggling to keep up appearances, but playing a beaten game. Alcala does not admit defeat. It is generally full, and many of its inmates pay high rents. But, nevertheless, it has failed in its object. It came into the world to be a haunt of fashion, and it is not. Fashion looked on Alcala in its early days, found it good, stayed a while, then passed in her own capricious way to other houses, newer, larger, more worthy of her patronage. A motley horde swept in and filled the vacant rooms.

BOUT Alcala, as about many other of New York’s apartment houses, there is something a little pathetic. It resembles a decayed gentleman struggling to keep up appearances, but playing a beaten game. Alcala does not admit defeat. It is generally full, and many of its inmates pay high rents. But, nevertheless, it has failed in its object. It came into the world to be a haunt of fashion, and it is not. Fashion looked on Alcala in its early days, found it good, stayed a while, then passed in her own capricious way to other houses, newer, larger, more worthy of her patronage. A motley horde swept in and filled the vacant rooms.

The schedule of prices at Alcala is like a badly rolled cigarette, thick in the middle and thin at both ends. The rooms halfway up are expensive, some of them almost as expensive, as if Fashion, instead of being gone forever, were still lingering. The top rooms are cheap, and the ground-floor rooms cheaper still.

Cheapest of all was Rutherford Maxwell’s hall bedroom. Its furniture was of the simplest. It consisted of a chair, another chair, a worn carpet, and a folding bed. The folding bed had an air of depression and baffled hopes. For years it had been trying to look like a bookcase in the daytime, and now it looked more like a folding bed than ever. There was also a plain deal table, much stained with ink. At this, night after night, sometimes far into the morning, its tenant would sit and write stories. Now and then it happened that one would be a good story and find a market.

Rutherford Maxwell was an Englishman, and the younger son of an Englishman; and his lot was the lot of the younger sons all the world over. He was by profession one of the numerous employees of the New Arctic Bank, a sound, trustworthy institution, with branches all over the world; and steady-going relations would assure Rutherford that he was lucky to have a berth in it. Rutherford did not agree with them. However sound and trustworthy, it was not exactly romantic. Nor did it err on the side of over-lavishness to those who served it. Rutherford’s salary was small. So were his prospects—if he remained in the bank. At a very early date he had registered a vow that he would not. And the road that led out of it for him was the uphill road of literature.

He was thankful for small mercies. Fate had not been over kind up to the present, but at last she had dispatched him to New York, the centre of things, where he would have the chance to try, instead of to some spot off the map. Whether he won or lost, at any rate he was in the ring, and could fight. So every night he sat in Alcala, and wrote. Sometimes he would only try to write, and that was torture.

There is never an hour of the day or night when Alcala is wholly asleep. The middle of the house is a sort of chorus-girl belt, while in the upper rooms there are reporters and other night birds. Long after he had gone to bed Rutherford would hear footsteps passing his door and the sound of voices in the passage. He grew to welcome them. They seemed to connect him with the outer world. But for them he was alone after he had left the office, utterly alone, as it is possible to be only in the heart of a great city. Some nights he would hear scraps of conversation, and at rare intervals a name.

He used to build up in his mind identities for the owners of the names. One in particular, Peggy, gave him much food for thought. He pictured her as bright and vivacious. This was because she sang sometimes as she passed his door. She had been singing when he first heard her name. “Oh, cut it out, Peggy,” a girl’s voice had said. “Don’t you get enough of that tune at the theatre?” He felt that he would like to meet Peggy.

June came, and July, making an oven of New York, bringing close, scorching days and nights, when the pen seemed made of lead; and still Rutherford worked on, sipping ice water, in his shirt sleeves, and filling the sheets of paper slowly, but with a dogged persistence which the weather could not kill. Despite the heat he was cheerful. Things were beginning to run his way a little now. A novelette, an airy trifle, conceived in days when the thermometer was lower and it was possible to think, and worked out almost mechanically, had been accepted by a magazine of a higher standard than those which hitherto had shown him hospitality. He began to dream of a holiday in the woods. The holiday spirit was abroad. Alcala was emptying itself. It would not be long before he, too, would be able to get away.

He was so deep in his thoughts that at first he did not hear the knocking at the door. But it was a constant knocking, and forced itself upon his attention. He rose and turned the handle.

Outside in the passage was a girl, tall and sleepy-eyed. She wore a picture hat and a costume the keynote of which was a certain aggressive attractiveness. There was no room for doubt as to which particular brand of scent was her favorite at the moment.

She gazed at Rutherfold dully. Like Banquo’s ghost, she had no speculation in her eyes. Rutherford looked at her inquiringly, somewhat conscious of his shirt sleeves.

“Did you knock?” he said, opening, as a man must do, with the inevitable foolish question.

The apparition spoke.

“Say,” she said, “got a cigarette?”

“I’m afraid I haven’t,” said Rutherford apologetically. “I’ve been smoking a pipe. I’m very sorry.”

“What?” said the apparition.

“I’m afraid I haven’t.”

“Oh!” A pause. “Say, got a cigarette?”

The intellectual pressure of the conversation was beginning to be a little too much for Rutherford. Combined with the heat, it made his head swim.

His visitor advanced into the room. Arriving at the table, she began fiddling with the things upon it. The pen seemed to fascinate her. She picked it up, and inspected it closely.

“Say, what d’you call this?” she said.

“That’s a pen,” said Rutherford soothingly. “A fountain pen.”

“Oh!” A pause. “Say, got a cigarette?”

Rutherford clutched a chair with one hand and his forehead with the other. He was in sore straits.

At this moment rescue arrived, not before it was needed. A brisk sound of footsteps in the passage, and there appeared in the doorway a second girl.

“What do you think you’re doing, Gladys?” demanded the newcomer. “You mustn’t come butting into folks’ rooms this way. Who’s your friend?”

“My name is Maxwell,” began Rutherford eagerly.

“What say, Peggy?” said the seeker after cigarettes, dropping a sheet of manuscript to the floor.

Rutherford looked with interest at the girl in the doorway. So this was Peggy. She was little and trim of figure. That was how he had always imagined her. Her dress was simpler than the other’s. The face beneath the picture hat was small and well-shaped, the nose delicately tiptilted, the chin determined, the mouth a little wide and suggesting good humor. A pair of gray eyes looked steadily into his before transferring themselves to the statuesque being at the table.

“Don’t monkey with the man’s inkwell, Gladys. Come along up to bed.”

“What? Say, got a cigarette?”

“There’s plenty upstairs. Come along.”

The other went with perfect docility. At the door, she paused, and inspected Rutherford with a grave stare.

“Good night, boy,” she said, with haughty condescension.

“Good night,” said Rutherford.

“Pleased to have met you. Good night.”

“Come along, Gladys,” commanded Peggy firmly.

Gladys went.

Rutherford sat down and dabbed at his forehead with his handkerchief, feeling a little weak. He was not used to visitors.

II.

He had lit his pipe, and was rereading his night’s work, preparatory to turning in, when there was another knock at the door. This time there was no waiting. He was in the state of mind when one hears the smallest noise.

“Come!” he cried.

It was Peggy.

Rutherford jumped to his feet.

“Won’t you——” he began, pushing the chair forward.

She seated herself with composure on the table. She no longer wore the picture hat, and Rutherford, looking at her, came to the conclusion that the change was an improvement.

“This’ll do for me,” she said. “Thought I’d just look in. I’m sorry about Gladys. She isn’t often like that. It’s the hot weather.”

“It is hot,” assented Rutherford.

“You’ve noticed it? Bully for you! Back to the bench for Sherlock Holmes! Did Gladys try to shoot herself?”

“Good heavens, no! Why?”

“She did once. But I stole her gun, and I suppose she hasn’t thought to get her another. She’s a good girl, really, only she gets like that sometimes in the hot weather.”

She looked round the room for a moment, then gazed unwinkingly at Rutherford.

“What did you say your name was?” she asked.

“Rutherford Maxwell.”

“Gee! That’s going some, isn’t it! Wants amputation, a name like that. I call it mean to give a poor, defenseless kid a cuss word like—what’s it? Rutherford? Haven’t you got something else some shorter—Tom, or Charles, or something?”

“I’m afraid not.”

The round, gray eyes fixed him again.

“I shall call you George,” she decided at last.

“Thanks; I wish you would,” said Rutherford.

“George it is, then. You can call me Peggy. Peggy Norton’s my name.”

“Thanks, I will.”

“Say, you’re English, aren’t you?”

“Yes. How did you know?”

“You’re so strong on the gratitude thing. It’s ‘thanks, thanks,’ all the time. Not that I mind it, George.”

“Thanks. Sorry—I should say ‘Oh, you Peggy!’ ”

She looked at him curiously.

“How d’you like New York, George?”

“Fine—to-night.”

“Been to Coney?”

“Not yet.”

“You should. Say, what do you do, George?”

“What do I do?”

“Cut it out, George. Don’t answer back as though we were a vaudeville team doing a cross-talk act. What do you do? When your boss crowds your envelope on to you, Saturdays, what’s it for?”

“I’m in a bank.”

“Like it?”

“Hate it.”

“Why don’t you quit, then?”

“Can’t afford to. There’s money in being in a bank. Not much, it’s true, but what there is of it is good.”

“What are you doing out of bed at this time of night? They don’t work you all day, do they?”

“No. They’d like to, but they don’t. I have been writing.”

“Writing what? Say, you don’t mind my putting you on the stand like this, do you? If you do, say so, and I’ll cut out the district-attorney act and talk about the weather.”

“Not a bit, really, I assure you. Please ask as many questions as you like.”

“Guess there’s no doubt about your being English, George. We don’t have time over here to shoot it off like that. If you’d have just said ‘Sure!’ I’d have got a line on your meanings. You don’t mind me doing schoolmarm, George, do you? It’s all for your good.”

“Sure,” said Rutherford, with a grin.

She smiled approvingly.

“That’s better! You’re little Willie, the apt pupil, all right. What were we talking about before we switched off onto the educational rail? I know, about your writing. What were you writing?”

“A story.”

“For a paper?”

“For a magazine.”

“What, one of the fiction stories about the Gibson hero and the girl whose life he saved, like you read?”

“That’s the idea.”

She looked at him with a new interest.

“Gee! George, who’d have thought it! Fancy you being one of the high-brows! You ought to hang out a sign. You look just ordinary.”

“Thanks.”

“I mean as far as the gray matter goes. I didn’t mean you were a bad looker. You’re not. You’ve got nice eyes, George.”

“Thanks.”

“I like the shape of your nose, too.”

“I say, thanks!”

“And your hair’s just lovely.”

“I say, really! Thanks awfully!”

She eyed him in silence for a moment. Then she burst out:

“You say you don’t like the bank?”

“I certainly don’t.”

“And you’d like to strike some paying line of business?”

“Sure.”

“Then why don’t you make your fortune by giving yourself out to a museum as the biggest human clam in captivity? That’s what you are. You sit there, just saying ‘thanks’ and ‘Bi Jawve, thanks, awfully,’ while a girl’s telling you nice things about your eyes and hair, and you don’t do a thing!”

Rutherford threw back his head, and roared with laughter.

“I’m sorry,” he said. “Slowness is our national failing, you know.”

“I believe you.”

“Tell me about yourself. You know all about me by now. What do you do besides brightening up the dull evenings of poor devils of bank clerks?”

“Give you three guesses.”

“Stage?”

“Gee! You’re the human sleuth, all right, all right. It’s a home run every time when you get your deductive theories unlimbered. Yes, George, the stage it is. I’m an actorine, one of the pony ballet in ‘The Island of Girls,’ at the Melody. Seen our show?”

“Not yet. I’ll go to-morrow.”

“Great! I’ll let them know, so that they can have the awning out and the red carpet down. It’s a cute little piece.”

“So I’ve heard.”

“Well, if I see you in front to-morrow, I’ll give you half a smile, so that you shan’t feel you haven’t got your money’s worth. Good night, George.”

“Good night, Peggy.”

She jumped down from the table. Her eye was caught by the photographs on the mantelpiece. She began to examine them.

“Who are these Willies?” she said, picking up a group.

“That is the football team of my old school. The lout with the sheepish smirk, holding the ball, is myself as I was before the cares of the world soured me.”

Her eyes wandered along the mantelpiece, and she swooped down on a cabinet photograph of a girl.

“And who’s this, George?” she said.

He took the photograph from her, and replaced it, with a curious blend of shyness and defiance, in the very centre of the mantelpiece. For a moment he stood looking intently at it, his elbows resting on the imitation marble.

“Who’s it?” asked Peggy. “Wake up, George. Who’s this?”

Rutherford started.

“Sorry,” he said. “I was thinking about something.”

“I bet you were. You looked like it. Well, who is she?”

“Eh? Oh, that’s a girl.”

Peggy laughed sarcastically.

“Thanks, awfully, as you would say. I’ve got eyes, George.”

“I noticed that,” said Rutherford, smiling. “Charming ones, too.”

“Gee! What would she say if she heard you talking like that?”

She came a step nearer, looking up at him. Their eyes met.

“She would say,” said Rutherford slowly: “ ‘Dickie’—she calls me Dickie, you know; she doesn’t like Rutherford any more than you do. She’d say: ‘Dickie, I know you love me, and I know I can trust you, and I haven’t the slightest objection to your telling Miss Norton the truth about her eyes. Miss Norton is a dear, good little sort; one of the best, in fact, and I hope you’ll be great pals!’ ”

There was a silence.

“She’d say that, would she?” said Peggy, at last.

“She would.”

Peggy looked at the photograph and back again at Rutherford.

“You’re pretty fond of her, George, I guess, aren’t you?”

“I am,” said Rutherford quietly.

There was another silence, a long one.

“George.”

“Yes?”

“George, she’s a pretty good long way away, isn’t she?”

She looked up at him with a curious light in her gray eyes. Rutherford met her glance steadily.

“Not to me,” he said. “She’s here now, and all the time.”

He stepped away, and picked up the sheaf of papers which he had dropped at Peggy’s entrance. Peggy laughed.

“Good night, George, boy,” she said. “I mustn’t keep you up any more, or you’d be late in the morning. And what would the bank do, then? Smash, or something, I guess. Good night, Georgie. See you again, one of these old evenings.”

“Good night, Peggy.”

The door closed behind her. He heard her footsteps hesitate, stop, and then move quickly on once more.

III.

He saw much of her after this first visit. Gradually, it became an understood thing between them that she should look in on her return from the theatre. He grew to expect her, and to feel restless when she was late. Once she brought the cigarette-loving Gladys with her, but the experiment was not a success. Gladys was languid, and rather overpoweringly refined, and conversation became forced. After that Peggy came alone.

Generally, she found him working. His industry amazed her.

“Gee! George,” she said one night, sitting in her favorite place on the table, from which he had moved a little pile of manuscripts to make room for her, “don’t you ever let up for a second? Seems to me you write all the time.”

Rutherford laughed.

“I’ll take a rest,” he said, “when there’s a bit more demand for my stuff than there is at present. When I’m in the twenty-cent-a-word class I’ll write once a month and spend the rest of my time traveling.”

Peggy shook her head.

“No traveling for mine,” she said. “Seems to me it’s just cussedness that makes people go away from Broadway when they’ve got plunks enough to stay there and enjoy themselves.”

“Do you like Broadway, Peggy?”

“Do I like Broadway! Does a kid like candy? Why, don’t you?”

“It’s all right for the time. It’s not my ideal.”

“Oh, and what particular sort of little old paradise do you hanker after?”

He puffed at his pipe, and looked dreamily at her through the smoke.

“Way over in England, Peggy, there’s a county called Worcestershire. And somewhere near the edge of that there’s a gray house, with gables; and there’s a lawn and a meadow and a shrubbery and an orchard and a rose garden and a big cedar on the terrace before you get to the rose garden. And if you climb to the top of that cedar, you can see the river through the apple trees in the orchard. And in the distance there are the hills. And——”

“Of all the rube joints!” exclaimed Peggy, in deep disgust. “Why, a day of that would be about twenty-three hours and a bit too long for me. Broadway for mine! Put me where I can touch Forty-second Street, without overbalancing, and then you can leave me. I never thought you were such a hayseed, George.”

“Don’t worry, Peggy. It’ll be a long time, I expect, before I go there. I’ve got to make my fortune first.”

“Getting anywhere near the John D. class yet?”

“I’ve still some way to go. But things are moving, I think. Do you know, Peggy, you remind me of a little Billiken, sitting on that table.”

“Thank you, George. I always knew my mouth was rather wide, but I did think I had Billiken to the bad. Do you do that sort of ‘candid-friend’ stunt with her?” She pointed to the photograph on the mantelpiece. It was the first time since the night when they had met that she had made any allusion to it. By silent agreement the subject had been ruled out between them. “By the way, you never told me her name.”

“Halliday,” said Rutherford slowly.

“What else?”

“Alice.”

“Don’t bite at me, George. I’m not hurting you. Tell me about her. I’m interested. Does she live in the gray house, with the pigs and chickens, and all them roses, and the rest of the rube outfit?”

“No.”

“Be chummy, George. What’s the matter with you?”

“I’m sorry, Peggy,” he said. “I’m a fool. It’s only that it all seems so damned hopeless. Here am I, earning about half a dollar a year, and—— Still, it’s no use kicking, is it? Besides, I may make a home run with my writing one of these days. That’s what I meant when I said you were a Billiken, Peggy. Do you know, you’ve brought me luck. Ever since I met you I’ve been doing twice as well. You’re my mascot.”

“Bully for me! We’ve all got our uses in the world, haven’t we? I wonder if it would help any if I was to kiss you, George?”

“Don’t you do it! One mustn’t work a mascot too hard.”

She jumped down, and came across the room to where he sat, looking down at him with the round, gray eyes that always reminded him of a kitten’s.

“George.”

“Yes?”

“Oh, nothing.”

She turned away to the mantelpiece, and stood gazing at the photograph, her back toward him.

“George.”

“Hello.”

“Say, what color eyes has she got?”

“Gray.”

“Like mine?”

“Darker than yours.”

“Nicer than mine?”

“Don’t you think we might talk about something else?”

She swung round, her fists clinched, her face blazing.

“Damn you and your blasted English haw-haw!” she cried. “I hate you! I do. I wish I’d never seen you! I wish——” She leaned on the mantelpiece, burying her face in her arms, and burst into a passion of sobs.

Rutherford leaped up, shocked and helpless. He sprang to her, and placed a hand gently on her shoulder.

“Peggy, old girl——”

She broke from him.

“Don’t you touch me! Don’t you do it! Gee! I wish I’d never seen you!”

She ran to the door, darted through, and banged it behind her.

Rutherford remained where he stood, motionless. For a full minute he did not move. Then, almost mechanically, he felt in his pocket for matches, and relit his pipe.

Half an hour passed. Then the door opened slowly. Peggy came in. She was pale, and her eyes were red. She smiled, a pathetic little smile.

“Peggy!”

He took a step toward her.

She held out her hand.

“I’m sorry, George; I feel mean.”

“Dear old girl, what rot!”

“I do. You don’t know how mean I feel. You’ve been real nice to me, George. Thought I’d look in and say I was sorry. Good night, George.”

He bent over her hand, and kissed it, and the next moment she was gone.

On the following night he waited, but she did not come. The nights went by, but still she did not come. And, one morning, reading his paper, he saw that “The Island of Girls” had gone West to Chicago.

IV.

Things were not running well for Rutherford. He had had his vacation, a golden fortnight of fresh air and sunshine in the Catskills, and was back in Alcala, trying, with poor success, to pick up the threads of his work. But, though the Indian summer had begun, and there was energy in the air, night after night he sat idle in his room, night after night went wearily to bed, oppressed with a dull sense of failure. He could not work. He was restless. His thoughts would not concentrate themselves.

Something was wrong; and he knew what it was, though he fought against admitting it to himself. It was the absence of Peggy that had brought about the change. Not till now had he realized to the full how greatly her visits had stimulated him. He had called her laughingly his mascot; but the thing was no joke. It was true. Her absence was robbing him of the power to write. It was absurd, he tried to tell himself. A little chorus girl, uneducated, living in another world from himself. He fought against the idea. But he could not kill it.

He was lonely. For the first time since he had come to New York he was really lonely. Solitude had not hurt him till now. In his black moments it had been enough for him to look up at the photograph on the mantelpiece, and he had been alone no longer. But now—the photograph had lost its magic. It could not hold him. Always his mind would wander back to the little black-haired ghost that sat on the table, smiling at him, and questioning him with its gray eyes.

And the days went by, unvarying in their monotony. And always the ghost sat on the table, smiling at him.

With the fall came the reopening of the theatres. One by one the electric signs blazed out along Broadway, spreading the message that the dull days were over, and New York was itself again. At the Melody, where, ages ago, “The Island of Girls” had run its light-hearted course, a new musical piece was in rehearsal. Alcala was full once more. The nightly snatches of conversation outside his door had recommenced. He listened for her voice, but he never heard it. He sat up, waiting, into the small hours; but she did not come. Once—he had been trying to write, and had fallen, as usual, to brooding—there was a soft knock at the door. In an instant he had bounded from his chair and turned the handle. It was one of the reporters from upstairs, who had run out of matches. Rutherford gave him a handful. The reporter went out, wondering what the man had laughed at.

There is balm in Broadway, especially by night. Depression vanishes before the cheerfulness of the great white way when the lights are lit and the human tide is in full flood. Rutherford had developed of late a habit of patrolling the neighborhood of Forty-second Street at theatre time. He found it did him good. There is a gayety, a bonhomie in the atmosphere of the New York streets, which acts like a charm on a man who has been used to dour, unfriendly London. Rutherford loved to stand on the sidewalk, and watch the passers-by, weaving stories round them.

One night his wanderings had brought him to Herald Square. The theatres were just emptying themselves. This was the time he liked best. He drew to one side to watch, and as he moved he saw Peggy.

She was standing at the corner, buttoning a glove. He was by her side in an instant.

“Peggy!” he cried.

She was looking pale and tired, but the color came back to her cheeks as she held out her hand. There was no trace of embarrassment in her manner, only a frank pleasure at seeing him again.

“Where have you been?” he said. “I couldn’t think what had become of you.”

She looked at him curiously.

“Did you miss me, George?”

“Miss you? Of course I did! My work’s been going all to pieces since you went away.”

“I only came back last night. I’m in the new piece at the Madison. Gee! I’m tired, George. We’ve been rehearsing all day.”

He took her by the arm.

“Come along and have some supper. You look worn out. By Jove, Peggy, it’s good, seeing you again. Can you walk as far as Rector’s, or shall I carry you?”

“Guess I can walk that far. But Rector’s? Has your rich uncle died and left you a fortune, George?”

“Don’t you worry, Peggy. This is an occasion. I thought I was never going to see you again. I’ll buy you the whole hotel, if you like.”

“Just supper’ll do, I guess. You’re getting quite the rounder, George.”

“You bet I am. There are all sorts of sides to my character you’ve never so much as dreamed of.”

They seemed to know Peggy at Rector’s. Paul beamed upon her paternally. One or two men turned, and looked after her as she passed. The waiters smiled slight, but friendly, smiles. Rutherford, intent on her, noticed none of these things.

Despite her protests, he ordered an elaborate and expensive supper. He was particular about the wine. The waiter, who had been doubtful about him, was won over, and went off to execute the order, reflecting that it was never safe to judge a man by his clothes, and that Rutherford was probably one of these eccentric young millionaires who didn’t care how they dressed.

“Well?” said Peggy, when he had finished.

“Well?” echoed Rutherford.

“You’re looking brown, George.”

“I’ve been away in the Catskills.”

“Still as strong on the rube proposition as ever?”

“Yes. But Broadway has its points, too.”

“Oh, you’re beginning to see that? Gee! I’m glad to be back. I’ve had enough of the wild West. If anybody ever tries to steer you west of Eleventh Avenue, George, don’t you go. There’s nothing doing. How have you been making out at your writing stunt?”

“Pretty well, but I wanted you. I was lost without my mascot. I’ve got a story in this month’s Wilson’s. A long story, and paid accordingly. That’s why I’m able to go about giving suppers to great actresses.”

“I read it on the train,” said Peggy. “It’s dandy. Do you know what you ought to do, George? You ought to turn it into a play. There’s a heap of money in plays.”

“I know. But who wants a play by an unknown man?”

“I know who would want ‘Willie in the Wilderness’ if you made it into a play; and that’s Winfield Knight. Ever see him?”

“I saw him in ‘The Outsider.’ He’s clever.”

“He’s it, if he gets a part to suit him. If he doesn’t he don’t amount to a row of beans. It’s just a gamble. This thing he’s in now is no good. The part doesn’t begin to fit him. In a month he’ll be squealing for another play so’s you can hear him in Connecticut.”

“He shall not squeal in vain,” said Rutherford. “If he wants my work, who am I that I should stand in the way of his simple pleasures? I’ll start on the thing to-morrow.”

“I can help you some, too, I guess. I used to know Winfield Knight. I can put you wise on lots of things about him that’ll help you work up Willie’s character so’s it’ll fit him like a glove.”

Rutherford raised his glass.

“Peggy,” he said, “you’re more than a mascot. You ought to be drawing a big commission on everything I write. It beats me how any of these other fellows ever write anything without you there to help them. I wonder what’s the most expensive cigar they keep here? I must have it, whatever it is. Noblesse oblige. We popular playwrights mustn’t be seen in public smoking any cheap stuff.”

It was Rutherford’s artistic temperament which, when they left the restaurant, made him hail a taxicab. Taxicabs are not for young men drawing infinitesimal salaries in banks, even if those salaries are supplemented at rare intervals by a short story in a magazine. Peggy was for returning to Alcala by car; but Rutherford refused to countenance such an anticlimax. Just as the mild man, as he casts off his mildness for a space, becomes for the time being a swashbuckler, and goes about seeking truculently for causes of offense, so does the impecunious man, playing at being rich, look round him for fresh excuses for spending money.

Peggy nestled into the corner of the cab with a tired sigh, and there was silence as they moved smoothly up Broadway.

He peered at her in the dim light. She looked very small and wistful and fragile. Suddenly, an intense desire surged over him to pick her up and crush her to him. He fought against it. He tried to fix his thoughts on the girl at home, to tell himself that he was a man of honor. His fingers, gripping the edge of the seat, tightened, till every muscle of his arm was rigid.

The cab, crossing a rough piece of road, jolted Peggy from her corner. Her hand fell on his.

“Peggy!” he cried hoarsely.

Her gray eyes were wet. He could see them glisten. And then his arms were round her, and he was covering her upturned face with kisses.

The cab drew up at the entrance to Alcala. They alighted in silence, and without a word made their way through into the hall. From force of habit Rutherford glanced at the letter rack on the wall at the foot of the stairs. There was one letter in his pigeonhole. Mechanically, he drew it out; and, as his eyes fell on the handwriting, something seemed to snap inside him.

He looked at Peggy, standing on the bottom stair, and back again at the envelope in his hand. His mood was changing with the violence that left him physically weak. He felt dazed, as if he had wakened out of a trance.

With a strong effort, he mastered himself. Peggy had mounted a few steps, and was looking back at him over her shoulder. He could read the meaning now in the gray eyes.

“Good night, Peggy,” he said, in a low voice.

She turned, facing him, and for a moment neither moved.

“Good night,” said Rutherford again.

Her lips parted, as if she were about to speak, but she said nothing.

Then she turned again, and began to walk slowly upstairs.

He stood watching her till she had reached the top of the long flight. She did not look back.

V.

The devil has many weapons in his armory for the undoing of man where woman is concerned, and the greatest of these is propinquity. Absence may make the heart grow fonder; but, in the case of a man, it generally, as the song says, makes it grow fonder of some one else. Photography has made great strides, but the time has still to come when a photograph can hold its own against flesh and blood.

Peggy’s nightly visits began afresh, and the ghost on the table troubled Rutherford no more. His restlessness left him. He began to write with a new vigor and success. In after years he wrote many plays, most of them good, clear-cut pieces of work, but none that came from him with the utter absence of labor which made the writing of “Willie in the Wilderness” a joy. He wrote easily, without effort. And always Peggy was there, helping, stimulating, encouraging.

Sometimes when he came in after dinner to settle down to work he would find a piece of paper on his table covered with her schoolgirl scrawl. It would run somewhat as follows:

He is proud of his arms. They are skinny, but he thinks them the limit. Better put in a short-sleeves scene for Willie somewhere.

He thinks he has a beautiful profile. Couldn’t you make one of the girls say something about Willie having the goods in that line?

He is crazy about golf.

He is proud of his French accent. Couldn’t you make Willie speak a little piece in French?”

“He” being Winfield Knight.

And so, little by little, the character of Willie grew till it ceased to be the Willie of the magazine story, and became Winfield Knight himself, with improvements. The task began to fascinate Rutherford. It was like planning a pleasant surprise for a child. “He’ll like that,” he would say to himself, as he wrote in some speech enabling Willie to display one of the accomplishments, real or imagined, of the absent actor. Peggy read it, and approved. It was she who suggested the big speech in the second act, where Willie described the progress of his love affair in terms of the links. From her, too, came information as to little traits in the man’s character which the stranger would not have suspected.

As the play progressed, he was amazed at the completeness of the character he had built. It lived. Willie in the magazine story might have been any one. He fitted into the story, but you could not see him. He had no real individuality. But Willie in the play—he felt that he would recognize him in the street. There was all the difference between the two that there is between a nameless figure in some cheap picture and a portrait by Sargent. There were times when the story of the play seemed thin to him and the other characters wooden, but in his blackest moods he was sure of Willie. All the contradictions in the character rang true. The humor, the pathos, the surface vanity covering a real diffidence, the strength and weakness fighting one another.

“You’re alive, my son,” said Rutherford admiringly, as he read the sheet. “But you don’t belong to me.”

At last there came the day when the play was finished, when the last line was written, and the last possible alteration made; and, later, the day when Rutherford, bearing the brown-paper-covered package under his arm, called at the Players’ Club to keep an appointment with Winfield Knight.

Almost from the first Rutherford had a feeling that he had met the man before, that he knew him. As their acquaintance progressed the feeling grew. Then he understood. This was Willie, and no other. Little turns of thought, little expressions—they were all in the play.

The actor paused in a description of how he had almost beaten a champion at golf, and looked at the parcel.

“Is that the play?” he said.

“Yes,” said Rutherford. “Shall I read it?”

“Guess I’ll just look through it myself. Where’s act one? Here we are. Have a cigar while you’re waiting.”

Rutherford settled himself in his chair, and watched the other’s face. For the first few pages, which contained some tame dialogue between minor characters, it was blank.

“Enter Willie,” he said. “Am I Willie?”

“I hope so,” said Rutherford, with a smile. “It’s the star part.”

“H’m!”

He went on reading. Rutherford watched him with furtive keenness. There was a line coming at the bottom of the page which he was then reading which ought to hit him; an epigram on golf, a whimsical thought put almost exactly as he had put it himself when telling his golf story.

The shot did not miss fire. The chuckle from the actor and the sigh of relief from Rutherford were almost simultaneous.

Winfield Knight turned to him.

“That’s a dandy line about golf,” said he.

Rutherford puffed at his cigar.

“There’s lots more of them in the piece,” he said.

“Bully for you!” said the actor, and went on reading.

Nearly an hour passed before he spoke again. Then he looked up.

“It’s me,” he said. “It’s me, all the time. I wish I’d seen this before I put on the punk I’m doing now. This is me from the drive off the tee. It’s great. Say, what’ll you have?”

Rutherford leaned back in his chair, his mind in a whirl. He had arrived at last. His struggles were over. He would not admit of the possibility of the play being a failure. He was a made man. He could go where he pleased, and do as he pleased.

It gave him something of a shock to find how persistently his thoughts refused to remain in England. Try as he might to keep them there, they kept flitting back to Alcala.

VI.

“Willie in the Wilderness” was not a failure. It was a triumph. Principally, it is true, a personal triumph for Winfield Knight. Every one was agreed that he had never had a part that suited him so well. Critics forgave the blunders of the piece for the sake of the principal character. The play was a curiously amateurish thing. It was only later that Rutherford learned craft and caution. When he wrote “Willie” he was a colt, rambling unchecked through the field of playwriting, ignorant of its pitfalls. But, with all its faults, “Willie in the Wilderness” was a success. It might, as one critic pointed out, be more of a monologue act for Winfield Knight than a play; but that did not affect Rutherford.

It was late on the opening night when he returned to Alcala. He had tried to get away earlier. He wanted to see Peggy. But Winfield Knight, flushed with success, was in his most expansive mood. He seized upon Rutherford, and would not let him go. There was supper—a gay, uproarious supper—at which everybody seemed to be congratulating everybody else. Men he had never met before shook him warmly by the hand. Somebody made a speech, despite the efforts of the rest of the company to prevent him. Rutherford sat there, dazed, out of touch with the mood of the party. He wanted Peggy. He was tired of all this excitement and noise. He had had enough of it all. All he asked was to be allowed to slip away quietly and go home. He wanted to think, to try and realize what all this meant to him.

At length the party broke up in one last explosion of handshaking and congratulations; and, eluding Winfield Knight, who proposed to take him off to his club, he started to walk up Broadway.

It was late when he reached Alcala. There was a light in his room. Peggy had waited up to hear the news.

She jumped off the table as he came in.

“Well?” she cried.

Rutherford sat down, and stretched out his legs.

“It’s a success,” he said. “A tremendous success.”

Peggy clapped her hands.

“Bully for you, George! I knew it would be. Tell me all about it. Was Winfield good?”

“He was the whole piece. There was nothing in it but he.” He rose, and placed his hands on her shoulders. “Peggy, old girl, I don’t know what to say. You know as well as I do that it’s all owing to you that the piece has been a success. If I hadn’t had your help——”

Peggy laughed.

“Oh, beat it, George,” said she. “Don’t you come jollying me. I look like a high-brow playwright, don’t I? No, I’m real glad you’ve made a hit, George, but don’t start handing out any story about it not being your own. I didn’t do a thing.”

“You did. You did everything.”

“I didn’t. But, say, don’t let’s start quarreling. Tell me more about it. How many calls did you take?”

He told her all that had happened. When he had finished, there was a silence.

“I guess you’ll be quitting soon, George,” said Peggy, at last. “Now that you’ve made a home run. You’ll be going back to that rube joint, with the cows and hens; isn’t that it?”

Rutherford did not reply. He was staring thoughtfully at the floor. He did not seem to have heard.

“I guess that girl’ll be glad some to see you,” she went on. “Shall you cable to-morrow, George? And then you’ll get married, and go and live in the rube house, and become a regular hayseed, and——” She broke off suddenly, with a catch in her voice. “Gee!” she whispered, half to herself. “I’ll be sorry when you go, George.”

He sprang up.

“Peggy!”

He seized her by the arm. He heard the quick intake of her breath. He gripped her till she winced with the pain.

“Peggy, listen! I’m not going back. I’m never going back. I’m a cad, I’m a hound. I know I am. But I’m not going back. I’m going to stay here with you. I want you, Peggy. Do you hear? I want you.”

She tried to draw herself away, but he held her.

“I love you, Peggy. Peggy, will you be my wife?”

There was utter astonishment in her gray eyes.

“Your wife?”

Her face was very white.

“Will you, Peggy?”

“You’re hurting me.”

He dropped her arm.

“Will you, Peggy?”

“No!” she cried.

He drew back.

“No!” she cried sharply, as if it hurt her to speak. “I wouldn’t play you such a mean trick. I’m too fond of you, George. There’s never been anybody just like you. You’ve been mighty good to me. I’ve never met a man who treated me like you. You’re the only real white man that’s ever happened to me, and I guess I’m not going to play you a low-down trick like spoiling your life. George, I thought you knew. Honest, I thought you knew. How did you think I lived in a swell place like this, if you didn’t know? How did you suppose every one knew me at Rector’s? How did you think I’d managed to find out so much about Winfield Knight?”

She drew a long breath, then hurried on.

“I was with Winfield Knight a year. That’s how I know him. And he wasn’t the first. Nor the last. I——”

He interrupted her hoarsely.

“Is there any one now, Peggy?”

“Yes,” she said, “there is.”

“You don’t love him, Peggy, do you?”

“Love him?” She laughed bitterly. “No, I don’t love him.”

“Then come to me, dear,” he said simply.

She shook her head in silence. Rutherford sat down, his chin resting in his hands. She came across to him, and smoothed his hair.

“It wouldn’t do, George,” she said. “Honest, it wouldn’t do. Listen. When we first met, I—I rather liked you, George, and I was mad with you for being so fond of the other girl, and taking no notice of me—not in the way I wanted, and I tried. Gee, I feel mean! It was all my fault. I didn’t think it would matter. There didn’t seem no chance then of your being able to go back and have the sort of good time you wanted; and I thought you’d just stay here, and we’d be pals, and—— But now you can go back, it’s all different. I couldn’t keep you. It would be too mean. You see, you don’t really want to stop. You think you do, but you don’t.”

“I love you,” he insisted.

“You’ll forget me. It’s all just a Broadway dream, George. Think of it like that. Broadway’s got you now, but you don’t really belong. You’re not like me. It’s not in your blood so’s you can’t get it out. It’s the chickens and roses you want really. Just a Broadway dream. That’s what it is. George, when I was a kid I remember crying and crying for a lump of candy in the window of a store till one of my brothers up and bought it for me, just to stop the racket. Gee! For about a minute I was the busiest thing that ever happened. And then it didn’t seem to interest me no more. Broadway’s like that for you, George. You go back to the girl and the cows and all of it. It’ll hurt some, I guess, but I reckon you’ll be glad you did.”

She stooped swiftly, and kissed him on the forehead.

“I’ll miss you, dear,” she said softly, and was gone.

Rutherford sat on, motionless. Outside, the blackness changed to gray, and the gray to white. He got up. He felt very stiff and cold.

“A Broadway dream!” he muttered.

He went to the mantelpiece, and took up the photograph. He carried it to the window, where he could see it better. A shaft of sunlight pierced the curtains and fell upon it.

Thanks to Gus Caywood for sharing a scan of this rare first magazine appearance.

Notes:

Wodehouse readers have known this story from its appearance in The Man Upstairs and other stories (1914), substantially similar to its London Magazine appearance in 1911, and indeed reference works have always called it a 1911 story. Keen-eyed catalogers at the FictionMags Index found that it had appeared in People’s Magazine in November 1909; this pulp fiction magazine was often thought beneath the notice of librarians, and due to its cheap paper, most copies have not survived the years. We are pleased to present this version of the story, with some minor but very significant differences from the British magazine and book texts.

Wodehouse readers have known this story from its appearance in The Man Upstairs and other stories (1914), substantially similar to its London Magazine appearance in 1911, and indeed reference works have always called it a 1911 story. Keen-eyed catalogers at the FictionMags Index found that it had appeared in People’s Magazine in November 1909; this pulp fiction magazine was often thought beneath the notice of librarians, and due to its cheap paper, most copies have not survived the years. We are pleased to present this version of the story, with some minor but very significant differences from the British magazine and book texts.

Along with sharing the magazine scans, Gus Caywood noted that the 1909 date is “significant, since the story is both autobiographical (drawn from PGW’s earliest days at the Hotel Earle), and soppier than anything else he was writing.” Given that the abbreviation of 11IA is still established in the latest edition of Who’s Who in Wodehouse, it is too late to revise the basic abbreviation, but this 1909 appearance, coded 11IAa, is still to be regarded as the earliest text of the story we have.

Most notably, the opening two paragraphs of the US version were condensed into one for the UK text; Maxwell works at the New Arctic rather than New Asiatic Bank in this edition; Peggy’s confession at the denouement is rather more explicit. An editor’s hand at one magazine or the other (or perhaps both) is also notable in frequent changes to punctuation, spelling, paragraphing, and other copy-editing details not annotated here.

Other differences and other ties to the year 1909 are discussed in the notes below.

folding bed: Probably the sort known in the USA as a Murphy bed, which tilts up into a wall closet, cabinet, or bookshelf to allow a one-room apartment to look like a living room in the daytime and to serve as a bedroom at night.

deal: Of furniture: made of a light softwood such as pine or fir.

younger son of an Englishman: Maxwell is like Wodehouse himself in this regard; Plum was the second of four sons. Unlike the landed and titled families to which he was a not-very-distant cousin, Wodehouse didn’t expect that his own elder brother would enjoy the right of primogeniture and scoop in all the family estate. But for Rutherford Maxwell, as for other younger sons in the canon such as Galahad Threepwood, a younger son’s lot did not come with great expectations of wealth.

New Arctic Bank: Changed to New Asiatic Bank for the UK editions. As in Psmith in the City, this is a transparent pseudonym for the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank, at which Wodehouse himself was employed from 1900 to 1902.

salary was small…uphill road of literature: Wodehouse earned £80 per annum at his bank, and like Maxwell, wrote at home late into the night in order to throw off his servitude to a bank and to become an established and full-time freelance author.

picture hat: A wide-brimmed woman’s hat, typically elaborately decorated with flowers or feathers. The magazine cover image at the head of these notes is an excellent example of the fashion.

Banquo’s ghost…no speculation: See Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse. The use of italics to emphasize names of fictional characters is a long-discarded typographical convention, here as with Willie below.

shirt sleeves: In this era, a man in mixed company in any sort of social setting would feel underdressed without wearing a suit jacket. Even as late as Bill the Conqueror, ch. 3 §3 (1924), Bill West, expecting his roommate Judson, opens the door to Flick Sheridan without having put on collar, coat, or shoes, and thinks of his condition as semi-nude.

intellectual pressure of the conversation: See the notes to A Damsel in Distress.

the nose delicately tiptilted: See the notes to A Damsel in Distress for a partial list of other Wodehouse heroines with this appealing feature.

cuss word: American dialect for “curse word” or profanity; cited in the OED from US sources beginning in 1863, including an 1872 quotation from Mark Twain.

Coney: Coney Island, an amusement park development on a peninsula at the southern end of the borough of Brooklyn, New York City. This is among the earliest references so far found in Wodehouse.

your boss crowds your envelope on to you: Wodehouse records what must have been current slang, in a sense not precisely recorded in the OED. The closest is crowd, v.1, 6a, “to press (things) in numbers on a person”; however, the latest citation in that sense is from 1856, and here there is only one thing being pressed.

putting you on the stand: The UK texts clarify this to “witness-stand.”

the Gibson hero and the girl whose life he saved: See “Rule Sixty-Three” for another story in which such a hero saves a girl from drowning; the end notes to that story have a Charles Dana Gibson illustration showing the type of man described.

actorine: The feminine “-ine” suffix as in heroine was more widely used then than now; searches for the Wodehousean adjective butlerine meaning butler-like also turn up noun usages for a female butler. OED citations for actorine as a female actor include an 1892 US newspaper calling it “the newest word in the profession” and a quotation from George Ade’s 1896 Artie, which may well have been Wodehouse’s introduction to the word.

pony ballet: a dance routine in a musical show performed by a chorus of dancers, usually all of the same short stature and identically dressed, performing high kicks and other synchronized movements, or the group of such dancers (“ponies”). First OED citation is from the New York Times in 1899.

Melody: The only period citation so far found for a New York theater of that name is in a fictional story, so this may well be a Wodehouse invention.

cabinet photograph: A popular size of photographic portrait, usually a thin photographic print mounted on a stiffer card measuring 4¼ by 6½ inches.

Dickie: Alice’s nickname for Rutherford is omitted from the familiar British texts of this story.

twenty-cent-a-word class: One site reports that even today, the median price received by freelance writers is between 25 and 50 cents per word, and quotes Ring Lardner in the 1920s as saying he would “rather write for the New Yorker at five cents a word than for Cosmopolitan at one dollar a word.” The first report of a dollar-per-word rate comes from 1908, when publications were vying for Theodore Roosevelt’s report of his post-presidential hunting trip. In those days before television and talking pictures supplanted reading for recreation, the fiction magazines had much higher circulations than today, so that they could pay authors a relatively higher rate.

write once a month: Reminiscent of Rocky Todd in “The Aunt and the Sluggard” (1916).

for mine: in the sense of “for me; as my choice” is used by Wodehouse only in the speech of his American characters.

plunks: Dollars; see “The Gem Collector” (1909), in which Jimmy Pitt equates “Plunks. Dollars. Doubloons.” For a reference to an article with more slang equivalents, see the final end note to “Kid Brady—Light-Weight” (1905).

rube: an unsophisticated or naïve person, especially one from a rural area; derived from the name “Reuben”; as an adjective, unsophisticated or countrified. OED has an 1898 adjective citation followed by George Ade’s 1899 Fables in Slang, which we know Wodehouse read and relied upon for American dialect.

John D.: Rockefeller, of course, the richest American of his time (1839–1937); founder of the Standard Oil Company.

Billiken: a lucky charm figurine created by Florence Pretz, a Kansas City art teacher, design-patented in 1908 and sold to a Chicago company for marketing and exploitation. The figure has been variously described as infantile, monkey-like, and dwarfish; it has a pointy head with a small central tuft of hair, pointed ears, and a wide, mischievous grin. More at Wikipedia. Wodehouse caught on to the fad in such stories as this and “Ahead of Schedule” (1910/11), “The Pitcher and the Plutocrat” (1910), “Ruth in Exile” (1912). As late as 1953, Mrs. Spottsworth uses the name as a nickname for Bill Belfry in Ring for Jeeves.

“Damn you and your blasted English haw-haw!”: This sentence was omitted in British texts. OED gives citations for “haw-haw” as a characterization of a hesitant or affected type of upper-class British speech dating back to 1841.

With the fall came the reopening of the theatres: In those days before air conditioning, theatres were uncomfortably hot during the New York summer, so they typically were closed. Some after-dark entertainment venues opened on roof gardens as an alternative, to allow the cooler night air to give patrons relief from the warmth of the day, but most theatres did not have that architectural option.

great white way: a nickname, usually capitalized elsewhere, for the theatrical section of New York’s Broadway, one of the first streets to have electric street lighting. As early as 1880, a mile-long stretch was illuminated by arc lamps, and soon theatre marquees were using incandescent bulbs to spell out their names and the names of their shows and stars.

Herald Square: At Broadway, Sixth Avenue (now Avenue of the Americas), and 34th Street. Like Times Square, it is not square but triangular, and is named after a newspaper, the former New York Herald.

Madison: Unclear; the Madison Square Theatre on 24th Street between Sixth Avenue and Broadway had been demolished in 1908. Possibly the 1200-seat theatre in the second Madison Square Garden (1890–1925), better known for its large arena.

Rector’s: One of New York’s famed “lobster palaces” catering to the nouveau riche who enjoyed celebrating their Gilded Age wealth in public (the “old money” class dined at home or with friends). Rector’s, opened by Charles Rector in 1899 on West 44th Street, had the advantage of proximity to the theatre district compared to its rivals Delmonico’s and Sherry’s (see the end notes to Ch. IV of The Intrusions of Jimmy). But with the rise of theatrical business, including fame as “one of the places where sugar daddies entertained chorus girls,” it began to gain a “naughty reputation” (see this article for a detailed history including menus). A sex farce titled “The Girl from Rector’s” ran at Weber and Field’s Music Hall from February to June 1909, and no doubt influenced the characterization of Peggy Norton’s association with the place.

rounder: One who “does the rounds” of bars and nightclubs, a playboy or social butterfly.

Paul beamed upon her paternally: This is the real-life Paul Perret, headwaiter at Rector’s. A mention in a recent book tells how well known and respected he must have been. In the British version of the story, “Paul, the head waiter,” is specified in this sentence; apparently Wodehouse expected New York readers of People’s to recognize him by the first name allusion alone.

particular about the wine: Rutherford apparently came from a wealthy enough family to have learned proper food and wine pairings at home. The menus and discussion at the article also mentioned above give a sense for the attention that Rector’s gave to their wine-appreciating customers.

Wilson’s: Apparently a Wodehouse invention; at least not found in the FictionMags Index. The photographic magazine of that name does not seem to have carried fiction.

returning to Alcala by car: That is, streetcar.

covering her upturned face with kisses: Later in Wodehouse’s career, variants of this phrase (often with “burning kisses”) recur frequently in discussions of the Ickenham System, as in Uncle Dynamite, ch. 11 §ii and many other mentions (1948); in Cocktail Time, ch. 9 and many other mentions (1958); in Service with a Smile, ch. 10 §2 (1961); and in “Life with Freddie” in Plum Pie (1966). Similar displays of passion so described are found in Quick Service, ch. 15 (1940); The Mating Season, ch. 26 (1949); The Old Reliable, ch. 13 (1951); Pigs Have Wings, ch. 3 §ii (1952); Barmy in Wonderland, ch. 18 (1952); and in “The Right Approach” in A Few Quick Ones (1959).

In Stiff Upper Lip, Jeeves, ch. 21 (1963), Stiffy Byng wants to kiss Major Plank as described, but is dissuaded by Bertie.

The earliest literary precedent so far found is from a short story, “The Saving of Jim Moseby,” by Anthony Leland, in The Chap-Book, June 1, 1898: “Then, with quick outgushing of his breath, he caught her slender form close to his, covering her upturned face with hungry kisses.”

Paul Kent (Plum’s Literary Heroes) found a probable source for some of the later “burning” kisses in Edith M. Hull’s The Sheik (1921): “he covered her face with fierce, burning kisses.”

The devil has many weapons: This paragraph appears only in this US magazine version.

fonder of some one else: The libretto by Frank William Green to an 1876/77 London pantomime version of Jack and Jill contains the lines for Jill: “Absence but makes the heart grow fonder—oh! Fonder of someone else it should be though.” There is no way of knowing whether this is the song Wodehouse remembered, of course.

the progress of his love affair in terms of the links: This metaphor would become a main theme of the later golf stories, as Diego Seguí notes: “e.g. the parody of Tennyson’s Princess at the end of “Sundered Hearts.” Cf. also A Damsel in Distress, ch. 5: ”the fairway of love was dotted with more bunkers than any golf course he had ever played on in his life.”

a portrait by Sargent: John Singer Sargent (1856–1925), the leading portrait painter of his era. In “Leave It to Jeeves” (1916), Bruce Corcoran claims he has “worked that stunt that Sargent and those fellows pull—painting the soul of the sitter.”

punk: See the notes to Bill the Conqueror.

called at the Players’ Club: See Wikipedia for more. The Broadway Special chapter of The Wodehouse Society meets from time to time at this historic location. Wodehouse mentions it several other times, such as in Barmy in Wonderland, ch. 7 (1952): “Mr. Benham gave him the calm, dignified look which he might have given a bumptious young actor at the Player’s Club.”

“How many calls did you take?”: That is, curtain calls, during the applause at the end of the show.

white: in the sense of purity of soul.

“I was with Winfield Knight a year.”: The entire paragraph is omitted in the familiar British text.

—Notes by Neil Midkiff

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums