The Saturday Evening Post, February 5, 1916

JEEVES—my man, you know—is really a most extraordinary chap. So capable. Honestly, I shouldn’t know what to do without him. On broader lines he’s like those chappies who sit peering sadly over the marble battlements at the Pennsylvania Station in the place marked Inquiries. You know the Johnnies I mean. You go up to them and say: “When’s the next train for Melonsquashville, Tennessee?” And they reply, without stopping to think: “Two-forty-three, track ten, change at San Francisco.” And they’re right every time. Well, Jeeves gives you just the same impression of omniscience.

As an instance of what I mean, I remember meeting Monty Byng in Bond Street one morning, looking the last word in a gray check suit, and I felt I should never be happy till I had one like it. I dug the address of the tailors out of him and had them working on the thing inside the hour.

“Jeeves,” I said that evening, “I’m getting a check suit like that one of Mr. Byng’s.”

“Injudicious, sir,” he said firmly. “It will not become you.”

“What absolute rot! It’s the soundest thing I’ve struck for years.”

“Unsuitable for you, sir.”

Well, the long and the short of it was that the damn’ thing came home, and I put it on, and when I caught sight of myself in the glass I nearly swooned. Jeeves was perfectly right. I looked a cross between a music-hall comedian and a cheap bookie. Yet Monty had looked fine in absolutely the same stuff. These things are just Life’s mysteries, and that’s all there is to it.

But it isn’t only that Jeeves’ judgment about clothes is infallible. The man knows everything. There was the matter of that tip on the Lincolnshire. I forget now how I got it, but it had the aspect of being the real, red-hot tabasco.

“Jeeves,” I said—for I’m fond of the man and like to do him a good turn when I can—“if you want to make a bit of money have something on Wonderchild for the Lincolnshire.”

He shook his head. “I’d rather not, sir.”

“But it’s the straight goods. I’m going to put my shirt on him.”

“I do not recommend it, sir. The animal is not intended to win. Second place is what the stable is after.”

Perfect piffle, I thought, of course. How the deuce could Jeeves know anything about it? Still, you know what happened. Wonderchild led till he was breathing on the wire, and then Banana Fritter came along and nosed him out. I went straight home and rang for Jeeves.

“After this,” I said, “not another step for me without your advice. From now on consider yourself the brains of the establishment.”

“Very good, sir. I shall endeavor to give satisfaction.”

And he has, by Jove! I’m a bit short on brain myself: the old bean would appear to have been constructed more for ornament than for use, don’t you know; but give me five minutes to talk the thing over with Jeeves and I’m game to advise anyone about anything. And that’s why, when Bruce Corcoran came to me with his troubles, my first act was to ring the bell and put it up to Jeeves.

“Leave it to Jeeves,” I said.

I first got to know Corky when I came to New York. He was a pal of my cousin Gussie, who was in with a lot of people who had studios down Washington Square way.

I don’t know if I ever told you about it, but the reason I left England was because I was sent over by my Aunt Agatha to try to stop young Gussie’s marrying a girl on the vaudeville stage, and I got the whole thing so balled up that I decided it would be a sound scheme for me to stop on in America for a bit instead of going back and having long, cozy chats about the thing with Aunt. So I sent Jeeves out to find a decent apartment and settled down for a bit of exile.

I’m bound to say that New York’s a topping place to be exiled in. Everybody was awfully good to me, and there seemed to be plenty of things going on, and I’m a wealthy bird; so everything was fine. Chappies introduced me to other chappies, and so on and so forth, and it wasn’t long before I knew squads of the right sort, some who rolled in the stuff in houses up by the Park and others who lived with the gas turned down mostly round Washington Square—artists and writers, and so forth. Brainy coves.

Corky was one of the artists. A portrait painter he called himself, but he hadn’t painted any portraits. He was sitting on the side lines, with a blanket over his shoulders, waiting for a chance to get into the game. You see, the catch about portrait painting—I’ve looked into the thing a bit—is that you can’t start painting portraits till people come along and ask you to, and they won’t come and ask you to until you’ve painted a lot first. This makes it kind of difficult for a chappie.

Corky managed to get along by drawing an occasional picture for the comic papers—he had rather a gift for funny stuff when he got a good idea—and doing bedsteads and chairs and things for the advertisements.

His principal source of income, however, was derived from biting the ear of a rich uncle—one Alexander Worple, who was in the jute business. I’m a bit foggy as to what jute is, but it’s apparently something the populace is pretty keen on, for Mr. Worple had made quite an indecently large stack out of it.

Now a great many fellows think that having a rich uncle is a pretty soft snap; but, according to Corky, such is not the case. Corky’s uncle was a robust sort of cove who looked like living forever. He was fifty-one, and it seemed as if he might go to par. It was not this, however, that distressed poor old Corky, for he was not bigoted and had no objection to the man’s going on living. What Corky kicked at was the way the above Worple used to harry him.

Corky’s uncle, you see, didn’t want him to be an artist. He didn’t think he had any talent in that direction. He was always urging him to chuck Art and go into the jute business, and start at the bottom and work his way up. Jute had apparently become a sort of obsession with him. He seemed to attach almost a spiritual importance to it. And what Corky said was that, while he didn’t know what they did at the bottom of a jute business, instinct told him that it was something too beastly for words. Corky, moreover, believed in his future as an artist. Some day, he said, he was going to make a hit. Meanwhile, by using the utmost tact, he was inducing his uncle to cough up very grudgingly a small quarterly allowance.

He wouldn’t have got this if his uncle hadn’t had a hobby. Mr. Worple was peculiar in this respect. As a rule, from what I’ve observed, the American captain of industry doesn’t do anything out of business hours. When he has put the cat out and locked up the office for the night he just relapses into a state of coma, from which he emerges only to start being a captain of industry again. But Mr. Worple in his spare time was what is known as an ornithologist. He had written a book called American Birds, and was writing another, to be called More American Birds. When he had finished that the presumption was he would begin a third, and keep on till the supply of American birds gave out.

Corky used to go to him about once every three months and let him talk about American birds. Apparently you could do what you liked with old Worple if you gave him his head first on his pet subject; so these little chats used to make Corky’s allowance all right for the time being. But it was pretty rotten for the poor chap. There was the frightful suspense, you see; and, apart from that, birds, except when broiled and in the society of a cold bottle, bored him stiff.

To complete the character study of Mr. Worple, he was a man of extremely uncertain temper, and his general tendency was to think that Corky was a poor chump, and that whatever step he took in any direction on his own account was just another proof of his innate idiocy. I should imagine Jeeves feels very much the same about me.

So when Corky trickled into my apartment one afternoon, shooing a girl in front of him, and said, “Bertie, I want you to meet my fiancée, Miss Singer,” the aspect of the matter that hit me first was precisely the one he had come to consult me about. The very first words I spoke were: “Corky, how about your uncle?”

The poor chap gave one of those mirthless laughs. He was looking anxious and worried, like a man who has done the murder all right, but can’t think what the deuce to do with the body.

“We’re so scared, Mr. Wooster,” said the girl. “We were hoping that you might suggest a way of breaking it to him.”

Muriel Singer was one of those small, quiet, appealing girls who have a way of looking at you with their big eyes as if they thought you were the greatest thing on earth and wondered that you hadn’t got onto it yet yourself. She sat there in a sort of shrinking way, looking at me as if she were saying to herself: “Oh, I do hope this great, strong man isn’t going to hurt me!” She gave a fellow a protective kind of feeling, made him want to stroke her hand and say, “There, there, little one!”—or words to that effect.

She made me feel that there was nothing I wouldn’t do for her. She was rather like one of those innocent-tasting American drinks which creep imperceptibly into your system, so that, before you know what you’re doing, you’re starting out to reform the world by force if necessary, and pausing on your way to tell the large man in the corner that if he looks at you like that you will knock his head off. What I mean is, she made me feel alert and dashing, like a jolly old knight-errant, or something of that kind. I felt that I was with her in this thing to the limit.

“I don’t see why your uncle shouldn’t be most awfully bucked,” I said to Corky. “He will think Miss Singer the ideal wife for you.”

Corky declined to cheer up.

“You don’t know him. Even if he did like Muriel, he wouldn’t admit it. That’s the sort of pig-headed guy he is. It would be a matter of principle with him to kick. All he would consider would be that I had gone and taken an important step without asking his advice, and he would raise Cain automatically. He’s always done it.”

I strained the old bean to meet this emergency.

“You want to work it so that he makes Miss Singer’s acquaintance without knowing you know her. Then you come along ——”

“But how can I work it that way?”

I saw his point. That was the catch.

“There’s only one thing to do,” I said.

“What’s that?”

“Leave it to Jeeves.” And I rang the bell.

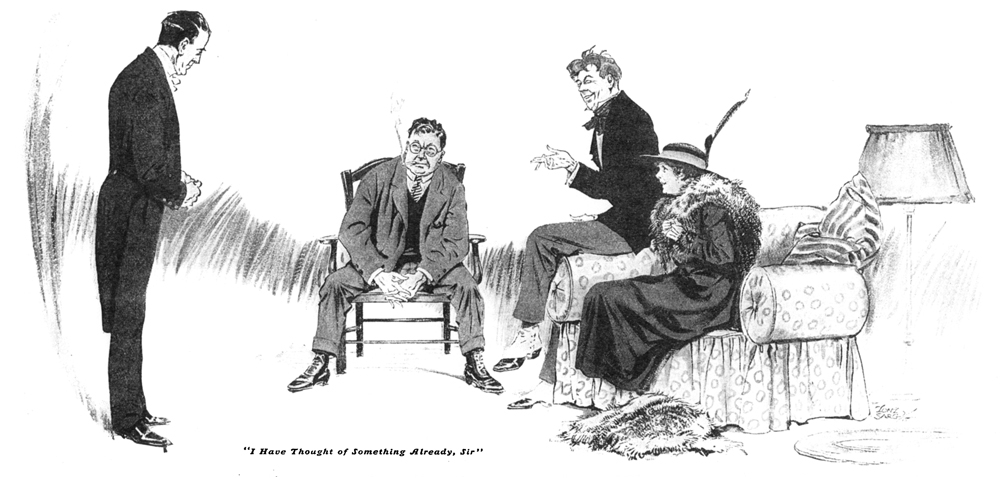

“Sir?” said Jeeves, kind of manifesting himself.

One of the rummy things about Jeeves is that, unless you watch out like a hawk, you very seldom see him come into a room. He’s like one of those weird chappies in India who dissolve themselves into thin air and nip through space in a sort of disembodied way and assemble the parts again just where they want them. I’ve got a cousin who’s what they call a theosophist, and he says he’s often nearly worked the thing himself, but couldn’t quite bring it off, probably owing to having fed in his boyhood on the flesh of animals slain in anger, and pie.

The moment I saw the man standing there, registering respectful attention, a weight seemed to roll off my mind. I felt like a lost child who spots his father in the offing. There was something about him that gave me absolute confidence.

Jeeves is a tallish man, with one of those dark, shrewd faces. His eye gleams with the light of pure intelligence.

“Jeeves, we want your advice.”

“Very good, sir.”

I boiled down Corky’s painful case into a few well-chosen words.

“So you see what it amounts to, Jeeves. We want you to suggest some way by which Mr. Worple can make Miss Singer’s acquaintance without getting onto the fact that Mr. Corcoran already knows her. Understand?”

“Perfectly, sir.”

“Well, try to think of something.”

“I have thought of something already, sir.”

“You have?”

“The scheme I would suggest cannot fail of success, but it has what may seem to you a drawback, sir, in that it requires a certain financial outlay.”

“He means,” I translated to Corky, “that he has got a pippin of an idea, but it’s going to cost a bit.”

Naturally the poor chap’s face dropped, for this seemed to dish the whole thing. But I was still under the influence of the girl’s melting gaze and I saw that this was where I started in as the knight-errant.

“You can count on me for all that sort of thing, Corky,” I said. “Only too glad. Carry on, Jeeves.”

“I would suggest, sir, that Mr. Corcoran take advantage of Mr. Worple’s attachment to ornithology.”

“How on earth did you know that he was fond of birds?”

“It is the way these New York apartments are constructed, sir. Quite unlike our London houses. The partitions between the rooms are of the flimsiest nature. With no wish to overhear, I have sometimes heard Mr. Corcoran expressing himself with a generous strength on the subject I have mentioned.”

“Oh! Well?”

“Why should not the young lady write a small volume, to be entitled—let us say—The Children’s Book of American Birds, and dedicate it to Mr. Worple? A limited edition could be published at your expense, sir, and a great deal of the book would, of course, be given over to eulogistic remarks concerning Mr. Worple’s own larger treatise on the same subject. I should recommend the dispatching of a presentation copy to Mr. Worple immediately on publication, accompanied by a letter in which the young lady asks to be allowed to make the acquaintance of one to whom she owes so much. This would, I fancy, produce the desired result; but, as I say, the expense involved would be considerable.”

I felt like the proprietor of a performing dog on the vaudeville stage when the tike has just pulled off his trick without a hitch. I had bet on Jeeves all along and I had known that he wouldn’t let me down. It beats me sometimes why a man with his genius is satisfied to hang round pressing my clothes and what not. If I had half Jeeves’ brain I should have a stab at being Prime Minister or something.

“Jeeves,” I said, “that is absolutely ripping! One of your very best efforts.”

“Thank you, sir.”

The girl made an objection:

“But I’m sure I couldn’t write a book about anything. I can’t even write good letters.”

“Muriel’s talents,” said Corky, with a little cough, “lie more in the direction of the drama, Bertie. I didn’t mention it before, but one of our reasons for being a trifle nervous as to how Uncle Alexander will receive the news is that Muriel is in the chorus of that show, Choose Your Exit, at the Manhattan. It’s absurdly unreasonable, but we both feel that that fact might increase Uncle Alexander’s natural tendency to kick like a steer.”

I saw what he meant. Goodness knows there was fuss enough in our family when I tried to marry into musical comedy a few years ago. And the recollection of my Aunt Agatha’s attitude in the matter of Gussie and the vaudeville girl was still fresh in my mind. I don’t know why it is—one of these psychology sharps could explain it, I suppose—but uncles and aunts, as a class, are always dead against the drama, legitimate or otherwise. They don’t seem able to stick it at any price.

But Jeeves had a solution, of course:

“I fancy it would be a simple matter, sir, to find some impecunious author who would be glad to do the actual composition of the volume for a small fee. It is only necessary that the young lady’s name should appear on the title page.”

“That’s true,” said Corky. “Sam Patterson would do it for a hundred dollars. He writes a novelette, three short stories and ten thousand words of a serial for one of the all-fiction magazines under different names every month. A little thing like this would be nothing to him. I’ll get after him right away.”

“Fine!”

“Will that be all, sir?” said Jeeves. “Very good, sir.”

I always used to think that publishers had to be devilish intelligent fellows, loaded down with the gray matter; but I’ve got their number now. All a publisher has to do is to write checks at intervals, while a lot of deserving and industrious chappies rally round and do the real work. I know, because I’ve been one myself. I simply sat tight in the old apartment with a fountain pen, and in due season a topping shiny book came along.

I happened to be down at Corky’s place when the first copies of the Children’s Book of American Birds bobbed up. Muriel Singer was there, and we were talking of things in general when there was a bang at the door and the parcel was delivered.

It was certainly some book! It had a red cover, with a fowl of some species on it and, underneath, the girl’s name in gold letters. I opened a copy at random.

“Often of a spring morning,” it said at the top of page twenty-one, “as you wander through the fields you will hear the sweet-toned, carelessly flowing warble of the purple finch linnet. When you are older you must read all about him in Mr. Alexander Worple’s wonderful book, American Birds.”

You see? A boost for the uncle right away. Arid only a few pages later, there he was in the spotlight again in connection with the yellow-billed cuckoo. It was great stuff. The more I read, the more I admired the chap who had written it and Jeeves’ genius in putting us on to the wheeze. I didn’t see how the uncle could fail to drop. You can’t call a chap the world’s greatest authority on the yellow-billed cuckoo without rousing a certain disposition toward chumminess in him.

“It’s a cert!” I said.

“An absolute cinch!” said Corky.

And a day or two later he meandered up the Avenue to my apartment to tell me that all was well. The uncle had written Muriel a letter so dripping with the milk of human kindness that if he hadn’t known Mr. Worple’s handwriting Corky would have refused to believe him the author of it. Any time it suited Miss Singer to call, said the uncle, he would be delighted to make her acquaintance.

Shortly after this I had to go out of town. Divers sound sportsmen had invited me to pay visits to their country places, and it wasn’t for several months that I settled down in the city again. I had been wondering a lot, of course, about Corky, whether it all turned out right, and so forth; and my first evening in New York, happening to pop into a quiet sort of little restaurant, which I go to when I don’t feel inclined for the bright lights, I found Muriel Singer there sitting by herself at a table near the door.

Corky, I took it, was out telephoning. I went up and passed the time of day.

“Well, well, well, what?” I said.

“Why, Mr. Wooster! How do you do?”

“Corky round?”

“I beg your pardon?”

“You’re waiting for Corky, aren’t you?”

“Oh, I didn’t understand. No, I’m not waiting for him.”

It seemed to me that there was a sort of something in her voice—a kind of thingummy, you know.

“I say, you haven’t had a row with Corky, have you?”

“A row?”

“A spat, don’t you know—little misunderstanding—faults on both sides—er—and all that sort of thing?”

“Why, whatever makes you think that?”

“Oh, well, as it were, what? What I mean is—I thought you usually dined with him before you went to the theater.”

“I’ve left the stage now.”

Suddenly the whole thing dawned on me. I had forgotten what a long time I had been away.

“Why, of course, I see now! You’re married!”

“Yes.”

“How perfectly topping! I wish you all kinds of happiness.”

“Thank you so much. Oh, Alexander,” she said, looking past me, “this is a friend of mine—Mr. Wooster.”

I spun round. A chappie with a lot of stiff gray hair and a red sort of healthy face was standing there. Rather a formidable Johnnie, he looked, though quite peaceful at the moment.

“I want you to meet my husband, Mr. Wooster. Mr. Wooster is a friend of Bruce’s, Alexander.”

The old boy grasped my hand warmly, and that was all that kept me from hitting the floor in a heap. The place was rocking. Absolutely!

“So you know my nephew, Mr. Wooster?” I heard him say. “I wish you would try to knock a little sense into him and make him quit this playing at painting. But I have an idea that he is steadying down. I noticed it first that night he came to dinner with us, my dear, to be introduced to you. He seemed altogether quieter and more serious. Something seemed to have sobered him. . . . Perhaps you will give us the pleasure of your company at dinner to-night, Mr. Wooster? Or have you dined?”

I said I had. What I needed then was air, not dinner. I felt that I wanted to get into the open and think.

When I reached my apartment I heard Jeeves moving about in his lair. I called him.

“Jeeves,” I said, “now is the time for all good men to come to the aid of the party. A stiff b-and-s first of all, and then I’ve a bit of news for you.”

He came back with a tray and a long glass.

“Better have one yourself, Jeeves. You’ll need it.”

“Later on, perhaps; thank you, sir.”

“All right. Please yourself. But you’re going to get a shock. You remember my friend, Mr. Corcoran?”

“Yes, sir.”

“And the girl who was to slide gracefully into his uncle’s esteem by writing the book on birds?”

“Perfectly, sir.”

“Well, she’s slid. She’s married the uncle.”

He took it without blinking. You can’t rattle Jeeves.

“That was always a development to be feared, sir.”

“You don’t mean to tell me that you were expecting it?”

“It crossed my mind as a possibility.”

“Did it, by Jove! Well, I think you might have warned us!”

“I hardly liked to take the liberty, sir.”

Of course, as I saw after I had had a bite to eat and was in a calmer frame of mind, what had happened wasn’t my fault, if you came down to it. I couldn’t be expected to foresee that the scheme, in itself a crackajack, would skid into the ditch as it had done; but, all the same, I’m bound to admit that I didn’t relish the idea of meeting Corky again until Time, the great healer, had been able to get in a bit of soothing work.

I cut Washington Square out absolutely for the next few months. I gave it the complete miss-in-balk. And then, just when I was beginning to think I might safely pop down in that direction and gather up the dropped threads, so to speak, Time, instead of working the healing wheeze, went and pulled the most awful bone and put the lid on it. Opening the paper one morning I read that Mrs. Alexander Worple had presented her husband with a son and heir.

I was so darned sorry for poor old Corky that I hadn’t the heart to touch my breakfast. I told Jeeves to drink it himself. I was bowled over. Absolutely! It was the limit.

I hardly knew what to do. I wanted, of course, to rush down to Washington Square and grip the poor blighter silently by the hand; and then, thinking it over, I hadn’t the nerve. Absent treatment seemed the touch. I gave it him in waves.

But after a month or so I began to hesitate again. It struck me that it was playing it a bit low-down on the poor chap, avoiding him like this just when he probably wanted his pals to surge round him most. I pictured him sitting in his lonely studio with no company but his bitter thoughts, and the pathos of it got me to such an extent that I bounded straight into a taxi and told the driver to go all out for the studio.

I rushed in; and there was Corky, hunched up at the easel, painting away, while on the model throne sat a severe-looking female of middle age, holding a baby.

A fellow has to be ready for that sort of thing.

“Oh, ah!” I said, and started to back out.

Corky looked over his shoulder.

“Hello, Bertie! Don’t go. We’re just finishing for the day. That will be all this afternoon,” he said to the nurse, who got up with the baby and decanted it into a perambulator which was standing in the fairway.

“At the same hour to-morrow, Mr. Corcoran?”

“Yes, please.”

“Good afternoon.”

“Good afternoon.”

Corky stood there, looking at the door, and then he turned to me and began to get it off his chest. Fortunately he seemed to take it for granted that I knew all about what had happened; so it wasn’t as awkward as it might have been.

“It’s my uncle’s idea,” he said. “Muriel doesn’t know about it yet. The portrait’s to be a surprise for her on her birthday. The nurse takes the kid out ostensibly to get a breather and they beat it down here. If you want an instance of the irony of Fate, Bertie, get acquainted with this. Here’s the first commission I have ever had to paint a portrait, and the sitter is that human poached egg that has butted in and bunkoed me out of my inheritance. Can you beat it? I call it rubbing the thing in to expect me to spend my afternoons gazing into the ugly face of a little runt who to all intents and purposes has hit me behind the ear with a blackjack and swiped all I possess. I can’t refuse to paint the portrait, because if I did my uncle would stop my allowance; yet every time I look up and catch that kid’s vacant eye I suffer agonies.

“I tell you, Bertie, sometimes when he gives me the patronizing once-over and then turns away and is sick, as if it revolted him to look at me, I come within an ace of hogging the entire front page of the evening papers as the latest murder sensation. There are moments when I can almost see the headline—Promising Young Artist Beans Baby With Ax!”

I patted his shoulder silently. My sympathy for the poor old scout was too deep for words. I kept away from the studio for some time after that because it didn’t seem right to me to intrude on the poor chappie’s sorrow. Besides, I’m bound to say that nurse intimidated me. She reminded me so infernally of Aunt Agatha. She was the same gimlet-eyed type.

But one afternoon Corky called me on the phone.

“Bertie!”

“Hello!”

“Are you doing anything this afternoon?”

“Nothing special.”

“You couldn’t come down here, could you?”

“What’s the trouble? Anything up?”

“I’ve finished the portrait.”

“Good boy! Stout work!”

“Yes.” His voice sounded rather doubtful. “The fact is, Bertie, I’ve been trying to give it the unbiased double-o, and it doesn’t look quite right to me. There’s something about it. . . . My uncle’s coming in half an hour to inspect it and—I don’t know why it is, but I kind of feel I’d like your moral support!”

I began to see that I was letting myself in for something. The sympathetic coöperation of Jeeves seemed to me to be indicated.

“You think he’ll cut up rough?”

“He may.”

I threw my mind back to the red-faced chappie I had met at the restaurant and tried to picture him cutting up rough. It was only too easy. I spoke to Corky firmly on the telephone.

“I’ll come,” I said.

“Good!”

“But only if I may bring Jeeves!”

“Why Jeeves? What’s Jeeves got to do with it? Who wants Jeeves? Jeeves is the fool who suggested the scheme that has led ——”

“Listen, Corky, old top! If you think I am going to face that uncle of yours without Jeeves’ support you’re mistaken. I’d sooner go into a den of wild beasts and bite a lion on the back of the neck.”

“Oh, all right!” said Corky.

Not cordially, but he said it; so I rang for Jeeves and explained the situation.

“Very good, sir,” said Jeeves.

That’s the sort of chap he is. You can’t rattle him.

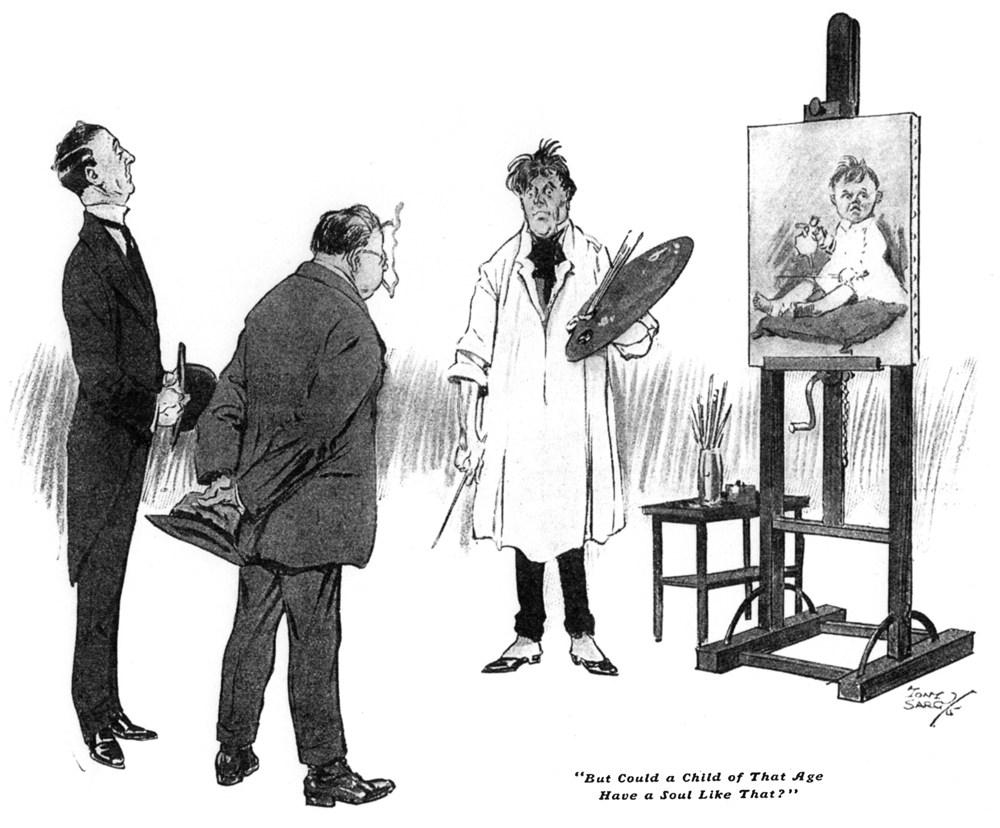

We found Corky near the door, looking at the picture, with one hand up in a defensive sort of way as if he thought it might swing on him.

“Stand right where you are, Bertie,” he said without moving. “Now tell me honestly: how does it strike you?”

The light from the big window fell right on the picture. I took a good look at it. Then I shifted a bit nearer and took another look. Then I went back to where I had been at first, because it hadn’t seemed quite so bad from there.

“Well?” said Corky anxiously.

I hesitated a bit.

“Of course, old man, I only saw the kid once, and then only for a moment; but—but it was an ugly sort of kid, wasn’t it, if I remember rightly?”

“As ugly as that?”

I looked again, and honesty compelled me to be frank.

“I don’t see how it could have been, old chap.”

Poor old Corky ran his fingers through his hair in a temperamental sort of way. He groaned.

“You’re quite right, Bertie. Something’s gone wrong with the darned thing. My private impression is that, without knowing it, I’ve worked that stunt that Sargent and those fellows pull—painting the soul of the sitter. I’ve got through the mere outward appearance and have put the child’s soul on canvas.”

“But could a child of that age have a soul like that? I don’t see how he could have managed it in the time. What do you think, Jeeves?”

“I doubt it, sir.”

“It—it sort of leers at you, doesn’t it!”

“You’ve noticed that too?” said Corky.

“I don’t see how one could help noticing.”

“All I tried to do was to give the little brute a cheerful expression. But, as it has worked out, he looks positively dissipated.”

“Just what I was going to suggest, old man. He looks as if he were in the middle of a colossal bat and enjoying every minute of it. Don’t you think so, Jeeves?”

“He has a decidedly inebriated air, sir.”

Corky was starting to say something, when the door opened and the uncle came in.

For about three seconds all was joy, jollity and good will. The old boy shook hands with me, slapped Corky on the back, said that he didn’t think he had ever seen such a fine day, and whacked his leg with his stick. Jeeves had projected himself into the background, and he didn’t notice him.

“Well, Bruce, my boy, so the portrait is really finished, is it?—really finished? Well, bring it out. Let’s have a look at it. This will be a wonderful surprise for your aunt. Where is it? Let’s ——”

And then he got it—suddenly, when he wasn’t set for the punch; and he rocked back on his heels.

“Oosh!” he exclaimed.

And for perhaps a minute there was one of the scaliest silences I’ve ever run up against.

“Is this a practical joke?” he said at last in a way that set about sixteen drafts cutting through the room at once.

I thought it was up to me to rally round old Corky.

“You want to stand a bit farther away from it,” I said.

“You’re perfectly right!” he snorted. “I do! I want to stand so far away from it that I can’t see the thing with a telescope!” He turned on Corky like an untamed tiger of the jungle who has just located a chunk of meat. “And this—this—is what you have been wasting your time and my money on for all these years! A painter! I wouldn’t let you paint a house of mine! I gave you this commission, thinking that you were a competent worker, and this—this—this extract from a comic colored supplement is the result.”

He swung toward the door, lashing his tail and growling to himself.

“This ends it! If you wish to continue this foolery of pretending to be an artist because you want an excuse for idleness, please yourself. But let me tell you this: Unless you report at my office on Monday morning, prepared to abandon all this idiocy and start in at the bottom of the business to work your way up, as you should have done half a dozen years ago, not another cent—not another cent—not another —— Boosh!”

Then the door closed and he was no longer with us. And I crawled out of the bombproof shelter.

“Corky, old top!” I whispered faintly.

Corky was standing staring at the picture. His face was set. There was a hunted look in his eye.

“Well, that finishes it!” he muttered brokenly.

“What are you going to do?”

“Do? What can I do? I can’t stick on here if he cuts off supplies. You heard what he said. I shall have to go to the office on Monday!”

I couldn’t think of a thing to say. I knew exactly how he felt about the office. I don’t know when I’ve been so infernally uncomfortable. It was like hanging round trying to make conversation to a pal who’s just been sentenced to twenty years in the coop.

And then a soothing voice broke the silence.

“If I might make a suggestion, sir!”

It was Jeeves. He had slid from the shadows and was gazing gravely at the picture. Upon my word, I can’t give you a better idea of the shattering effect of Corky’s Uncle Alexander when in action than by saying that he had absolutely made me forget for the moment that Jeeves was there.

“I wonder if I have ever happened to mention to you, sir, a Mr. Digby Thistleton, with whom I was once in service? Perhaps you have met him? He was a financier. He is now Lord Bridgnorth. It was a favorite saying of his that there is always a way. The first time I heard him use the expression was after the failure of a patent depilatory that he promoted.”

“Jeeves,” I said, “what on earth are you talking about?”

“I mentioned Mr. Thistleton, sir, because his was in some respects a parallel case to the present one. His depilatory failed, but he did not despair. He put it on the market again under the name of Tress-o, guaranteed to produce a full crop of hair in a few months. It was advertised, if you remember, sir, by a humorous picture of a billiard ball, before and after taking, and made such a substantial fortune that Mr. Thistleton was shortly afterward elevated to the peerage for services to the Liberal party. It seems to me that if Mr. Corcoran looks into the matter he will find, like Mr. Thistleton, that there is always a way.

“Mr. Worple himself suggested the solution of the difficulty. In the heat of the moment he compared the portrait to an extract from a colored comic supplement. I consider the suggestion a very valuable one, sir. Mr. Corcoran’s portrait may not have pleased Mr. Worple as a likeness of his only child, but I have no doubt that editors would gladly consider it as a foundation for a series of humorous drawings. If Mr. Corcoran will allow me to make the suggestion, his talent has always been for the humorous. There is something about this picture—something bold and vigorous—which arrests the attention. I feel sure it would be highly popular.”

Corky was glaring at the picture and making a sort of dry, sucking noise with his mouth. He seemed completely overwrought. And then suddenly he began to laugh in a wild way.

“Corky, old man!” I said, massaging him tenderly.

I feared the poor blighter was hysterical. He began to stagger about all over the floor.

“He’s right! The man’s absolutely right! Jeeves, you’re a life-saver! You’ve hit on the greatest idea of the age! Report at the office on Monday! Start at the bottom of the business! I’ll buy the business if I feel like it. I know the man who runs the comic section of the Sunday Star. He’ll eat this thing. He was telling me only the other day how hard it was to get a good new series. He’ll give me anything I ask for a real winner like this. Do you know what Bud Fisher gets for Mutt and Jeff?

“Have you any idea how much Outcault made out of Buster Brown? I’ve got a gold mine. Where’s my hat? I’ve got an income for life. Where’s that damned hat? Lend me a five-spot, Bertie. I want to take a taxi down to Park Row!”

Jeeves smiled paternally. Or, rather, he had a kind of paternal muscular spasm about the mouth, which is the nearest he ever gets to smiling.

“If I might make the suggestion, Mr. Corcoran—for a title of the series you have in mind—The Adventures of Baby Blobbs.”

Corky and I looked at the picture, then at each other, in an awed way. Jeeves was right. There could be no other title.

“Jeeves,” I said—it was a few weeks later and I had just finished looking at the comic section of the Sunday Star—“I’m an optimist. I always have been. The older I get, the more I agree with Shakspere and those poet Johnnies about it always being darkest before the dawn, and there’s a silver lining, and what you lose on the swings you make up on the roundabouts. Look at Mr. Corcoran, for instance. There was a fellow, one would have said, clear up to the eyebrows in the soup. To all appearances he had got it right in the neck. Yet look at him now! Have you seen these pictures?”

“I took the liberty of glancing at them before bringing them to you, sir. Extremely diverting.”

“They have made a big hit, you know.”

“I anticipated it, sir.”

I leaned back against the pillows.

“You know, Jeeves, you’re a genius! You ought to be drawing a commission on these things.”

“I have nothing to complain of in that respect, sir. Mr. Corcoran has been most generous. I am putting out the brown suit, sir.”

“No; I think I’ll wear the blue with the faint red stripe.”

“Not the blue with the faint red stripe, sir.”

“But I rather fancy myself in it.”

“Not the blue with the faint red stripe, sir.”

“Oh, all right; have it your own way.”

“Very good, sir. Thank you, sir.”

Of course I know it’s as bad as being henpecked; but then, Jeeves is always right. You’ve got to consider that—what?

Editor’s notes:

A somewhat revised version of this story appeared in The Strand Magazine, June 1916. Notes on further reprints and collected versions appear at the end of that link.

Jeeves, my man: Here, of course, man = manservant = valet = gentleman’s personal gentleman. Many people have the impression that Jeeves is a butler, but that title applies to the chief male servant in a large household, not to the sole employee of a bachelor like Bertie.

Pennsylvania Station: The original ornate granite and marble train station in Beaux-Arts style was built 1901–10 by the Pennsylvania Railroad between 7th and 8th Avenues, between 31st and 33rd Streets in Manhattan. The counter to the right of center rear in this image (opens in new window or tab) may be the Inquiries station mentioned. It was demolished in the 1960s and replaced with a fully underground train station.

Melonsquashville: Wodehouse’s made-up name for a Tennessee hamlet was previously used by Psmith, in the Captain serial Psmith, Journalist (November, 1909). It was carried over in 1912 into the American version of The Prince and Betty, with Psmith renamed Smith. Karen Shotting notes that “Life’s Little Incidents,” the final Notes of the Day item in the Globe newspaper, June 8, 1907, refers to Melonsquashville, Ga.; Wodehouse was in charge of the “By the Way” column at that time, and there is good evidence that the “By the Way” staff was responsible for the last Notes of the Day item as well.

San Francisco: Rather an out-of-the-way place to change trains if going from New York to Tennessee, as Karen Shotting points out. This is the same in American and British texts of the story, so I would guess that Wodehouse expected readers everywhere to recognize this and to feel superior to Bertie’s understanding of American geography.

the last word: the latest thing in fashion, probably adapted from French le dernier cri

Lincolnshire: The Lincolnshire Handicap was a one-mile horse race run in late March or early April at the Lincolnshire racetrack outside Lincoln in England, from 1860 to 1964, open to horses aged four years or older. Since 1965 it has been the Lincoln Handicap, run at Doncaster.

Banana Fritter: a fictitious winner; in 1915 the Lincolnshire winner was View Law.

Washington Square: a public park in the Greenwich Village area of Manhattan. Wodehouse lived in the Hotel Earle (now the Washington Square Hotel, see their website for historic photos) on Waverly Place, just across from its northern corner, in 1909–10, so was familiar with the Bohemian neighborhood of artists and writers.

I don’t know if I ever told you about it: See “Extricating Young Gussie” from a few months earlier in the same magazine. Much has been made by other Wodehouse commentators of the fact that the Bertie of the previous story was not explicitly named Wooster and seemed to be part of the Mannering-Phipps family, but it is clear to me from this and other references that Wodehouse intended his readers to think of this Bertie and that Bertie as the same man.

balled up: Originally American slang for clogged, tangled, confused; OED has citations from Mark Twain and George Ade, among other US authors read by Wodehouse. Not etymologically related to “balls up” from the mid-20th century in Britain; no testicular reference intended here.

jute: a coarse, long, strong vegetable fiber derived from the stalks of plants of genus Corchorus grown mainly in Bangladesh and India; used for rope, twine, sacking (burlap, hessian, gunny), mats, carpet backing, and other industrial textiles.

go to par: from the Latin for equal, par means 100 percent, or, in this usage, one hundred. The term is derived from the stock market of the day, in which securities were generally sold at a discount from their face value, or par value, based on expected future earnings. A stock was “below par” if the market value was trading at below face value. Today most stocks either have no par value or a very low one such as a penny, but bond trading still uses this term since there is a face value for a bond. In “All’s Well With Bingo” (1937), Bingo’s uncle Wilberforce “is eighty-six and may quite easily go to par.” Karen Shotting notes that Wodehouse used this phrase years later in a letter to Bill Townend on January 3, 1961: “I am eighty and may quite easily go to par. . .” (Author! Author!, 1962).

American Birds: Karen Shotting suggests American Ornithology (originally published 1808–1814) by Alexander Wilson as a possible source for Alexander Worple and his hobby; see Plum Lines, Autumn 2013, p. 1. I cannot help pointing to American Birds (1907) by William Lovell Finley as an example of popular writing on ornithology from Wodehouse’s own time, with a combination of personal style and scientific description; I have no other evidence linking it to the book Wodehouse may have had in mind.

give him his head: figuratively, let him direct the flow of conversation; from driving a horse-drawn carriage, where “giving the horse its head” means slackening the reins so the horse goes in the direction it wants to go.

bucked: as in the British “bucked up” for cheered or heartened; nothing to do with bucking in the bronco sense of resisting or throwing off a burden. Compare “kick” in Corky’s reply a couple of lines down, where he could, I suppose, have used the American sense of “buck,” though perhaps at the cost of some confusion.

raise Cain: slang, originally American, mid-19th century, for making a disturbance, causing an uproar.

makes [her] acquaintance without knowing you know her: Wodehouse used this trick in other stories, including “Romance at Droitgate Spa” (US Crime Wave at Blandings, UK Eggs, Beans and Crumpets, Vintage Wodehouse).

theosophist: a follower of the mystical doctrines of Helena Blavatsky. Wodehouse’s older brother Armine went to India to study this belief system and eventually became head of the Theosophical College at Benares.

animals slain in anger, and pie: presumably the first would make the soul too encumbered, and the second the body too heavy, for this spiritual transport. The Strand version of this passage omits the comma, and the book collections generally follow the Strand. My guess is that Wodehouse wrote it without the comma so as to make Bertie’s style seem funnier, and that the comma here was inserted by the magazine editors to avoid the false reading “slain in pie.” Karen Shotting points out that Robert A. Hall Jr. covered the grammar of this sentence (though not the comma) in a supplement to Plum Lines, vol. V, no. 5 in 1984.

registering: showing an emotion in one’s features, or displaying it by one’s stance or gestures. This sense is theatrical jargon from the early 20th century, much discussed during the days of silent movies. It was highlighted by quotation marks in the first mention I can find in Wodehouse:

Lord Emsworth adjusted his glasses, and the mild smile disappeared from his face, to be succeeded by a set look. A stage director of a moving-picture firm would have recognized the look. Lord Emsworth was “registering” interest. . . .

from Something New, chapter III, in the Saturday Evening Post, June 26, 1915, also in book form as Something Fresh.

Choose Your Exit: The show’s title is a humorous takeoff on the fire notice mandated by New York regulations to be printed at the beginning of every theatre program in the city. Here is a 1918 example:

I tried to marry into musical comedy: This sentence and the next were omitted when this story was adapted into “The Artistic Career of Corky” in Carry On, Jeeves (1925); by that time Bertie’s bachelor existence was more fully established, and his romantic entanglements were most often presented as inadvertent and unwanted.

legitimate: conventional theatre, “straight” plays as opposed to musical comedy, farce, revue, vaudeville, and the like. Derived from the legal authority of Britain’s Lord Chancellor to license plays, granted by the Licensing Act of 1737 and not revoked until 1968.

under different names: Wodehouse was at this time using several pseudonyms for his work in Vanity Fair; see also James Orlebar Cloyster’s passing off his work as the work of others in Not George Washington (1907).

gray matter: brain cells; Wodehouse is using this term before Agatha Christie published her first Hercule Poirot novel in which he praises his own “little grey cells” (The Mysterious Affair at Styles, 1920). See also “grey matter” in Wodehouse’s 1910 story The Intrusions of Jimmy.

the sweet-toned, carelessly flowing warble: Quoted from the article on the Purple Finch (Carpodacus purpureus) by Eugene P. Bicknell, in Frank W. Chapman’s Handbook of Birds of Eastern North America, p. 282 (third edition, 1896). [Thanks to John Dawson.]

Divers sound sportmen: Printed in the magazine with Sound capitalized, but that is surely a misprint; all other versions have it in lower case. The archaic word “divers” probably threw the typesetter off; it merely means “various” or “several.” The meaning surely is that various reliable fellows of sporting interest have invited Bertie for visits. I cannot find any reference to a body of water called “Divers Sound,” which some might think to be the meaning as printed in the magazine.

now is the time for all good men to come to the aid of the party: I had always been under the impression that Patrick Henry or another revolutionary-era hero had coined this, but it seems to have been invented as a typewriting exercise by Charles E. Weller in 1867, according to his 1918 book on The Early History of the Typewriter.

b-and-s: brandy and soda

crackajack: Variant form of cracker-jack, 1890s slang for something top-notch, first quality. The popcorn/peanuts/caramel candy was invented shortly after the first print appearances of the slang phrase, so it was not the source of the term. In this story as it appears in Strand and books, it is spelled cracker-jack, so it seems likely that the Saturday Evening Post altered the phrase so as not to seem to be advertising a product; this seems to have been their editorial policy. For instance, their 1940 serial of Quick Service omits naming a Packard car, instead calling it “the other big car.”

Time, the great healer: Often cited by Wodehouse; the phrase is a translation of a classical one, and appears in many variant forms in English, such as “Time heals all wounds.” The ancient Greek poet Menander (c. 342–292 b.c.) expressed it as

Πάντων τῶν κακῶν ἰατρός χρόνος ἐστί (“time is the best doctor for bad situations”).

Google Books has citations of Bertie’s form back to 1844: “I was told indeed that Time, the great Healer, would soften the bitterness of my regret” (Lewis Gaylord Clark, in a memoir of his deceased twin brother Willis Gaylord Clark.) The Hepworth Film Company (UK) produced a three-reel silent film with this title in 1914 starring Tom Powers and Alma Taylor.

miss-in-balk: Spelled miss-in-baulk in British editions; a term from billiards for a failure to hit the object ball, especially a deliberate miss, leaving the cue ball in a strategic position at the expense of adding a point to the opponent’s score. Two other Wodehouse usages of this as deliberate avoidance are in the OED citations for this phrase, from Not George Washington (1907) and Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit (1954). Not to be confused (as the Post editor or typesetter may have done) with a balk in baseball.

pulled the most awful bone: Paul Dickson’s The Dickson Baseball Dictionary finds the phrase “pull a bone” meaning to err, to commit a mistake, in Ty Cobb’s Busting ’Em and Other Big League Stories (1914).

put the lid on it: brought the situation to a close or climax, topped it off; OED citations begin in 1909, so this was a fairly new phrase.

drink it himself: At first one might think this was an indication that Bertie had a cocktail for breakfast, but in later stories he describes himself as an abstemious chap as a rule and states that he can do nothing nor see anyone in the morning until he has had his tea.

absent treatment: the Christian Science doctrine that a practitioner need not be near the patient in order to accomplish healing; also the title of a 1911 Wodehouse short story. Karen Shotting notes that the “By the Way” column frequently lampooned the idea.

standing in the fairway: the avid golfer Wodehouse seemingly cannot resist a reference even in the stories that have nothing to do with golf.

bunkoed: swindled, cheated; US slang from 1870s, often spelled “buncoed”; I have to guess that was Wodehouse’s original version, as the Strand and book versions have the anagram “bounced” here, which makes some sense, but is not nearly as vivid as what I surmise that Wodehouse wrote. I suspect the Strand editor is responsible for the change, either a misreading or a deliberate alteration for British readers. Ian Michaud notes that Wodehouse spelled it “buncoed” in two Kid Brady stories (here and here), a Vanity Fair column, a 1910 Globe article, and the American version of The Prince and Betty, giving some substantiation to my surmise.

I’ve been trying to give it the unbiased double-o: omitted in all other versions; one more bit of evidence that this is closest to Wodehouse’s original. The phrase “double-o” is US slang for an intense look (from the resemblance to a pair of eyes). OED’s first citation is from 1914.

Sargent: John Singer Sargent (1856–1925), American portrait painter. “What sitter can be sure that the sight of him won’t stir in Mr. Sargent the soul-unveiling impulse?” (New Republic, April 24, 1915)

a colossal bat: altered to “a colossal spree” in all other versions. OED has “bat” as originally US slang for a spree or binge, with citations back to 1848.

twenty years in the coop: “twenty years in quod” in all other versions. The meaning is of course “prison” in either case.

Tress-o: changed to “Hair-o” in all other versions.

the Liberal party: changed to “his party” in all other versions; here I suspect the Strand editor trying not to offend any reader.

Do you know what Bud Fisher gets for Mutt and Jeff? Have you any idea how much Outcault made out of Buster Brown?: Real comic strips in America, omitted in Strand and book versions of this story.

Baby Blobbs: Karen Shotting notes that a possible source for this name is the music-hall song “The Baby’s Name” (1900) by C. W. Murphy and A. S. Hall, in which the narrator, a Mr. Blobbs, complains that the Boer War news has filled his wife’s brain with names of battles and military leaders, and that when it was time to christen their first child, she told the parson:

The baby’s name is Kitchener, Carrington, Methuen, Kekewich, White;

Cronje, Plummer, Powell, Majuba,

Gatacre, Warren, Colenso, Kruger,

Cape Town, Mafeking, French, Kimberley, Ladysmith, ‘Bobs,’

Union Jack and Fighting Mac, Lyddite, Pretoria Blobbs.

A performance of the song is on YouTube.

‘Bobs’ is a nickname for Lord Roberts (Frederick Sleigh Roberts, 1st Earl Roberts, 1832–1914), commander of the British forces in the Second Boer War 1899–1900. Lord Roberts had a famous antipathy to cats, mentioned by Wodehouse in several stories (The Luck Stone, ch. 16; “Pillingshot’s Paper”; “The Man Who Disliked Cats”)

and no doubt an influence on Sir Roderick Glossop’s similar aversion to them (“Sir Roderick Comes to Lunch”).

as bad as being henpecked: The final paragraph was included in the Strand version, but omitted in the revision for Carry On, Jeeves as “The Artistic Career of Corky” in 1925.

—Transcription, images, and notes by Neil Midkiff, with contributions from Karen Shotting, Ian Michaud, and John Dawson

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums