Hot Water

by

P. G. Wodehouse

Literary and Cultural References

This is part of an ongoing effort by the members of the Blandings Yahoo! Group to document references, allusions, quotations, etc. in the works of P. G. Wodehouse.

Hot Water was originally annotated by Mark Hodson (aka The Efficient Baxter). The notes have been reformatted and edited somewhat, but credit goes to Mark for his original efforts, even while we bear the blame for errors of fact or interpretation. Additional notes added in 2020 and later by Neil Midkiff [NM] and others as credited below are flagged with * ; significantly altered earlier notes are flagged with ° .

The novel was serialized in the US Collier’s magazine from 21 May to 6 August 1932. It first appeared in book format on 17 August 1932 in the UK (Herbert

Jenkins, right), and simultaneously in the US (Doubleday, Doran, left), both under the same

title. Although David Jasen says the contents are identical, much editorial intervention, principally by the UK publisher, disproves his claim. The notes below do not refer to many purely copy-editorial changes in spelling, hyphenation of compound words, punctuation, italics, and the like; changes to or omission of words are annotated.

The novel was serialized in the US Collier’s magazine from 21 May to 6 August 1932. It first appeared in book format on 17 August 1932 in the UK (Herbert

Jenkins, right), and simultaneously in the US (Doubleday, Doran, left), both under the same

title. Although David Jasen says the contents are identical, much editorial intervention, principally by the UK publisher, disproves his claim. The notes below do not refer to many purely copy-editorial changes in spelling, hyphenation of compound words, punctuation, italics, and the like; changes to or omission of words are annotated.

The novel was later adapted by Wodehouse as the play The Inside Stand, first produced in London, 1935.

Page references are to the 1963 Penguin edition of Hot Water, in which the text runs from pp. 7–238, and in which the Jenkins text is used, though updated with current British punctuation rules (e.g. single quotation marks for speech). Both original editions used the traditional punctuation still in use in America. For those using other editions, here is a cross-reference table (link opens in a new browser tab or window) to the pagination of some other available editions.

|

Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 Chapter 6 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 9 |

Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Chapter 12 Chapter 13 Chapter 14 Chapter 15 Chapter 16 Chapter 17 Chapter 18 |

Chapter 1

Dedication (ch. 1, p. 5)

Maureen O’Sullivan (1911–1998). American actress who appeared in more than seventy films. Famous as Johnny Weismuller’s scantily-clad co-star in the Tarzan movies of the thirties, and as the mother of actress Mia Farrow. O’Sullivan and her husband the Australian writer John Farrow were personal friends of the Wodehouses.

Ethel is Wodehouse’s wife; Leonora his step-daughter, and Miss Winks and John-John are Pekingese dogs, the latter belonging to Miss O’Sullivan. Wodehouse was looking after it for her (cf. Performing Flea, letter dated 14 March 1931).

St. Rocque ... Château Blissac (ch. 1.1, p. 7) °

St. Roch (Rocco in Italian) is supposed to have been born in Montpellier, and distinguished himself caring for the victims of a plague in Italy. St. Rocque does not appear to exist as a placename in France in any of the variant spellings of the name. See below for more.

There is a place called La Rocque on Jersey; Wodehouse might have remembered this from the time he spent at a school on Guernsey. In ch. 2.6 (p. 60 of the Penguin paperback), St. Rocque is said to be in Brittany, as it is in French Leave (1956), where St. Rocque appears again.

Blissac also seems to be fictitious. Placenames in -ac appear most commonly in southern France, although not unknown in Brittany. In March 1932, Wodehouse was staying near Auribeau, a little way north of Cannes. The description of St. Rocque as a fishing village turned into a popular resort sounds rather like Cannes.

J. Wellington Gedge (ch. 1.1, p. 7)

Cf. the character in Gilbert & Sullivan’s The Sorcerer: “My name is John Wellington Wells / I’m a dealer in magic and spells.” Wellington is a town in Shropshire. The name Gedge possibly owes something to Broadway producer Crosby Gaige, 1882–1949, who is mentioned in passing in Bring On the Girls.

tubby (ch. 1.1, p. 7) *

Other characters described as tubby include Mr. Brewster and the Sausage Chappie (Indiscretions of Archie); Harold, the page boy (“The Purity of the Turf”); Sir Mallaby Marlowe (The Girl on the Boat/Three Men and a Maid, ch. 11 of book versions); the Right Hon. A. B. Filmer (“Jeeves and the Impending Doom”); Anatole (Right Ho, Jeeves); and Cosmo Blair (Spring Fever).

The nickname Tubby is used for Tubby Bridgnorth in If I Were You, Tubby Vanringham in Summer Moonshine, Sir Gregory Parsloe-Parsloe (in his young manhood) in Pigs Have Wings, and Tubby Frobisher in Ring for Jeeves.

Casino Municipale (ch. 1.1, p. 7) °

This is either Italian or an error: in French, it would be Casino Municipal. Most French seaside and spa towns have casinos, many of which are run by the municipality. The superfluous ‘e’ has disappeared in the Penguin edition when the term appears again on p. 13 and p. 139, but both US and UK first editions retain “Municipale” throughout.

heart was in the Highlands, a-chasing of the deer (ch. 1.1, p. 7)

My heart’s in the Highlands, my heart is not here;

My heart’s in the Highlands a-chasing the deer;

A-chasing the wild deer, and following the roe—

My heart’s in the Highlands wherever I go.

Farewell to the Highlands, farewell to the North,

The birth-place of valour, the country of worth:

Wherever I wander, wherever I rove,

The hills of the Highlands for ever I love.

Farewell to the mountains high cover’d with snow;

Farewell to the straths and green valleys below:

Farewell to the forests and wild-hanging woods;

Farwell to the torrents and loud-pouring floods.

My heart’s in the Highlands, my heart is not here,

My heart’s in the Highlands a-chasing the deer;

Chasing the wild deer, and following the roe—

My heart’s in the Highlands wherever I go.

Robert Burns: My Heart’s in the Highlands (1789)

Glendale, Cal. (ch. 1.1, p. 7)

Glendale lies a few miles north of Los Angeles, and is the third largest city in Los Angeles County.

Medway (ch. 1.1, p. 7)

The river Medway is a tributary of the Thames in the English county of Kent.

Moddom (ch. 1.1, p. 7) *

This is how Medway’s British accent when saying “Madam” would sound to a Californian ear. We learn later that this accent is an assumed one.

Big Chief (ch. 1.1, p. 8) *

Popularly supposed to be Native American terminology for the leader of a tribe. Most often used in Wodehouse for the head of an organization, as with Fillmore Nicholas (The Adventures of Sally), Sir George Pyke/Lord Tilbury (Bill the Conqueror, Heavy Weather, Frozen Assets), Lord Chuffnell (Thank You, Jeeves), J. B. Duff (Quick Service), Mr. Donaldson (Full Moon, “Life with Freddie”), Sir Aylmer Bostock (Uncle Dynamite), J. G. Anderson (Barmy in Wonderland), Colonel Savage (Bring On the Girls); or for the head of a family, as with Lord Bittlesham (“Bingo and the Little Woman”), Lord Blicester (“The Masked Troubadour”), Lord Worplesdon (Joy in the Morning) and Mr. Roddis (“Uncle Fred Flits By”). Jerry Nichols’s father (Bachelors Anonymous) fits both categories.

Only here and once in Cocktail Time is the term used for a forceful wife.

boat to England (ch. 1.1, p. 8) °

The fact that St. Rocque has a direct boat to England would put it somewhere in northern France, confirming the Brittany location mentioned elsewhere. Possibly it is a composite of Cannes and a resort such as Le Touquet or Deauville.

St. Rocque, normally, he found a boring spot (ch. 1.1, p. 8) *

US magazine serial and book simply have “he found boring” here.

Festival of the Saint (ch. 1.1, p. 8) °

The feast-day of St. Roch is on 17 August. But in ch. 4, p. 71, we read that the St. Rocque festival is on July 15; this may lead to the conclusion that Wodehouse intended St. Rocque to be a saint of his own invention rather than a variant spelling of St. Roch.

contributing his mite to the revels (ch. 1.1, p. 8) *

A possible allusion to the Biblical contribution of the widow’s mite (actually two mites; see Luke 21:2).

Venetian Suite (ch. 1.1, p. 8)

The Wodehouses slept in the Venetian Suite when they stayed with William Randolph Hearst in his castle at San Simeon in February 1931 (see Performing Flea, letter of February 25).

Miss Putnam (ch. 1.1, p. 8)

Possibly a reference to the famous New York publishing family. George H. Putnam had died in 1930.

featherweight (ch. 1.1, p. 8) *

In boxing terms, the featherweight class was established in 1889 for boxers up to 9 stone in weight (126 lb., 57.15 kg). Informally, as here, meaning one of slight build.

light-heavy (ch. 1.1, p. 8) *

In boxing terms, the light-heavyweight class was established in 1913 for boxers up to 12 stone 7 in weight (175 lb., 79.38 kg).

English Income Tax (ch. 1.1, p. 9)

One reason for Wodehouse’s move to France in 1931 was the difficulty he was having with the British and American tax authorities.

Philipson’s Mal-de-Mer-o (ch. 1.1, p. 9) *

Many of Wodehouse’s coinages for fictitious patent medicines and other drugstore items end in -o; Mulliner’s Buck-U-Uppo may be the most famous, but Slimmo (Pigs Have Wings, Uncle Dynamite) is a close runner-up; Peppo (“Ukridge Rounds a Nasty Corner”), Nervino (The Little Warrior), Sooth-o (Money for Nothing), Sneezo (“Rodney Has a Relapse”), and Stick-o (“There’s Always Golf!”) are others that come to mind.

Mal de mer is the French for seasickness.

bravely, for the Glendale Gedges have the right stuff in them (ch. 1.1, p. 9) *

The modern or Tom Wolfe sense of “character, grit” is one of the ways Wodehouse uses the phrase “right stuff.” Compare p. 210, below. See The Inimitable Jeeves.

A very charming young wild Indian (ch. 1.1, p. 10) *

Following this outdated reference to Native Americans, the US magazine serial and US book have the additional sentence “Haven’t you heard he’s celebrated as France’s leading souse?” Souse is originally US slang for a drunkard, first cited in the OED from Jack London in 1915; Wodehouse’s use in Laughing Gas (1936) is also an OED citation.

“Say, what is this joint?” (ch. 1.1, p. 10) *

For Say, see Piccadilly Jim. For joint, see Sam the Sudden.

Keeley Cure (ch. 1.1, p. 10)

Keeley, Leslie E. (1832–1900), American physician. Around 1879 he developed a treatment for chronic alcoholism and drug addiction, injecting institutionalized patients with a chloride of gold and allowing them unlimited access to liquor. Keeley claimed a very high rate of success with only a few relapses. The medical establishment dismissed him as a charlatan.

leaky cistern upstairs (ch. 1.1, p. 10) *

a leopard crouching for the spring (ch. 1.1, p. 10) *

The crouching leopard is a commonly-occurring image, e.g. in heraldry; it was also the symbol of Osiris in ancient Egypt. [MH]

Oakes sank into a chair like a crouching leopard, and placed the tips of his fingers together.

“The Education of Detective Oakes” (1914)

“He looks to me just like a crouching leopard.”

“The Nodder” (1933; in Blandings Castle and Elsewhere, 1935)

“You are,” she said (ch. 1.1, p. 11) *

Mrs. Gedge joins the category of ambitious wives who seek distinction for their husbands. Compare Eugenia Crocker in Piccadilly Jim, also eager to disprove her sister’s disparagement of her second husband, in this case by getting Bingley Crocker a British peerage; also see Emily Trotter in Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit, seeking a knighthood for L. G. Trotter in order to gain ascendancy over her social rival Mrs. Alderman Blenkinsop.

for the historian to touch but lightly (ch. 1.2, p. 11) *

Wodehouse frequently referred to himself in the character of narrator as “the historian”; see Bill the Conqueror.

left a pin in it (ch. 1.2, p. 11) *

See The Code of the Woosters for other such hypothetical punctures.

“Gosh darn it!” (ch. 1.2, p. 11) *

The US magazine serial and US book have “For crying out loud!” here. The oldest citation found by Google Books for the phrase is in a US college fraternity magazine from 1924, so it is not surprising that the UK editor replaced it.

noisy collision with a small table laden with glass and china (ch. 1.2, p. 11) *

An incomplete list of the instances where Wodehouse uses this type of accident for comic relief can be found in the notes to Stiff Upper Lip, Jeeves. As the late Terry Mordue wrote in his annotations to Leave It to Psmith, “No Blandings story is complete without the demise of an occasional table in the hall — it’s a wonder there are any ornaments left to display.”

heeby jeebies (ch. 1.2, p. 11) *

Printed as two words in Penguin, but hyphenated as heeby-jeebies in all original editions. The term was a recent coinage by cartoonist William de Beck, in the “Barney Google” comic strip for 26 October 1923; the citations in the OED suggest that his original intent was “a feeling of discomfort, apprehension, or depression.” Other senses of delirium tremens and of a jazz dance are cited in the later 1920s. Wodehouse first used it in “Jane Gets Off the Fairway” (1924; in The Heart of a Goof, 1926).

suttee … when an Indian dies (ch. 1.2, p. 12) *

Unlike the wild Indian previously mentioned (above, p. 10) here Mrs. Crocker is referring to a Hindu resident of India. The practice is somewhat fictionalized in the popular imagination, and had occurred mostly in a historical context, having been largely suppressed by legislation during the British colonial period in India.

picking at the coverlet (ch. 1.2, p. 13) *

See The Mating Season.

Hôtel des Étrangers (ch. 1.3, p. 13) °

Literally: Strangers’ Hotel or Foreigners’ Hotel. A common name for hotels in the South of France. There is an Hôtel des Étrangers in Cannes, also in Nice and Menton.

The Penguin typesetters were able to give the full diacritical markings as in French, as did the US magazine serial in Collier’s. Doubleday’s printer did not have the accented capital letters, so it appeared as Hôtel des Etrangers in the US first edition; the Herbert Jenkins UK first edition uses neither of the accent marks in the name.

a garden for the convenience of guests wishing to commit suicide (ch. 1.3, p. 13) *

Compare:

[Novelists’s] stories conjured up the Casino as a home of jovial revelry—tempered, true, by an occasional suicide, but on the whole distinctly jovial revelry.

“The Small Gambler” (1913)

Chez Jimmy (ch. 1.3, p. 13) °

A famous Paris bar in the Ménilmontant district of the 20th arrondisement, noted for jazz music. In French Leave, the Hotel Splendide at Roville-sur-Mer has a barman named Philippe, also formerly of Chez Jimmy.

New York Herald (ch. 1.3, p. 13)

Founded in 1835 by James Gordon Bennett, soon becoming famous as a cheap popular scandal sheet. It later achieved a high reputation for its foreign news coverage, and established a Paris edition for sale in continental Europe. The Continental Edition was the predecessor of the International Herald Tribune.

Soup Slattery … an expert safe-blower (ch. 1.3, p. 14) *

Soup’s nickname comes from the criminal jargon for a liquid explosive used in safe-cracking, a preparation of nitroglycerin extracted from the stabilizing solids of dynamite using hot water or alcohol. We never learn his given name.

Gordon Carlisle (ch. 1.3, p. 14) °

The original note by Mark Hodson reads:

Possibly the name is related to that of the composer Ivan Caryll (“Fabulous Felix”) who is mentioned a number of times in Bring On the Girls. Gordon “Oily” Carlisle is essentially the same character elsewhere called Soapy Molloy, although Soapy is of course married to Dolly.

I [NM] find neither of these suggestions convincing. Soapy Molloy is an older gentleman of senatorial appearance; his specialty is selling spurious shares in oil wells, and outside that métier he is limited in capability. The only impersonation he essays is that of pretending to be Thomas G. Gunn, the supposed father of his young wife Dolly. Gordon Carlisle is younger, smarter, and more versatile.

We meet Gordon Carlisle again, now married to Gertie, in Cocktail Time (1958).

His face … in repose resembled a slab of granite with suspicious eyes (ch. 1.3, p. 14) *

See Galahad at Blandings.

she went haywire (ch. 1.3, p. 15) *

Not only is this the earliest use so far found of haywire in Wodehouse, it predates the earliest citations in the OED of forms of the phrase to go haywire in the sense of becoming excited, distracted, or mentally unbalanced. (Earlier citations of the phrase are for machines or processes that go wrong, not for people.) I have submitted this citation to the online OED. [NM, 2025-05-24]

Wodehouse used it in both impersonal and personal senses:

“Then the passenger list has gone haywire. Who does this bijou interior set belong to, then?”

The Luck of the Bodkins, ch. 11 (1935)

“How was I to know you were going to go haywire and come to the castle?”

Spring Fever, ch. 14 (1948)

‘He’s gone all haywire over a girl.’

Bachelors Anonymous, ch. 8.2 (1973)

strictly on the up-and-up (ch. 1.3, p. 15) *

This time the OED already has this sentence from Hot Water in its citations for the sense of the phrase meaning honest, straightforward, ‘on the level’. But there is an earlier Wodehouse usage, dated from the magazine appearance of the first story below. I have submitted this one to the OED as well.

“Oh, it was all perfectly respectable, guv’nor. All strictly on the up-and-up. Purely a business relationship.”

“Lord Emsworth Acts for the Best” (1926; in Blandings Castle and Elsewhere, 1935)

You know that feeling you sometimes feel of feeling you’re feeling that something has happened which has happened before. I believe doctors explain it by saying that the two halves of the brain aren’t working strictly on the up-and-up.

“Fate” (1931; in Young Men in Spats, 1936)

‘Well, my dear old thing, I mean, now that you know that Bill’s relations with Lottie were strictly on the up-and-up, and realizing, as you must do, that he’s perfectly goofy about you, what I’m driving at is, why don’t you marry the poor old blighter and put him out of his misery?’

Doctor Sally, ch. 14 (1932)

“How about it, Soapy?”

“Maybe it’s on the up-and-up.”

Money in the Bank, ch. 10 (1942)

“Boy, could I write a book!” (ch. 1.3, p. 15) *

The Rodgers and Hart show tune “I Could Write a Book” might come to mind, but it was not written until 1940 for Pal Joey so cannot be the referent here.

hearts and flowers (ch. 1.3, p. 15)

Song: Music by Theodore Moses-Tobani (1893). Words (added in 1899) by Mary D. Brine. A standard of the cinema pianist’s repertoire for the romantic moments in silent films, and thus “hearts and flowers” came to mean sentimental romance in general.

Out amongst the flowers sweet,

Lingers pretty Marguerite,

Sowing with her hands so white,

Future blossoms, fair and bright.

And the sunbeams lovingly

Kiss sweet Marguerite for me

Kiss my little lady sweet,

Blue eyed gentle Marguerite!

When I say, “Oh Marguerite,

All my heart is at your feet,

Turn it to a garden fair,

See it blossom ’neath your care.

“Till it yields for you alone

Wond’rous fragrance all your own.

And its sweetest flowers shall grow,

For my Marguerite I know!”

Blushes deepen in her cheek,

Ere the shy red lips can speak,

“Ah! but what if weeds should grow,

Mongst the flowers you bid me sow?”

“Love will pluck them out,” I cry,

“Trust me, Marguerite so shy,

Let my heart your garden be,

Give the seeds of love to me.”

Mary D. Brine: Hearts and Flowers

you’d of thought (ch. 1.3, p. 15) *

Wodehouse is deliberately using a nonstandard spelling of the contraction “you’d’ve” (for “you would have”) to emphasize a lower-class American pronunciation, a marker for Soup Slattery’s speech here. Gertie uses it too, in “I’d of” in ch. 15, p. 187; so does Miss Putnam in ch. 17.5, p. 224, with “had of, I’d of” together in one sentence. But Gordon Carlisle does not, as he aspires to present himself more formally, as in “you would have thought” in a previous paragraph on this page. Nor do the other American characters, who are better-educated.

See also the discussion of could of in Leave It to Psmith.

Social Register (ch. 1.3, p. 15)

In the United States, some cities have, or used to have, a directory listing the names of those who are prominent in society.

she told me out of a blue sky, as you might say (ch. 1.3, p. 16) *

In the form out of a clear sky the OED has citations from the nineteenth century; Wodehouse gets the earliest credit in the OED for out of a blue sky from 1903.

But to spring an examination on you in the middle of the term out of a blue sky, as it were, was underhand and unsportsmanlike, and would not do at all.

“How Pillingshot Scored” (1903; in Tales of St. Austin’s, 1903)

This letter I’m telling you about arrived one morning out of a blue sky, as it were.

“Doing Clarence a Bit of Good” (1913; in My Man Jeeves, 1919)

For all practical purposes, it was a safe and sane Fourth provided out of a blue sky by the god of chance.

The White Hope, book 2, ch. 10 (1914)

The thing seemed to hit him suddenly, out of a blue sky.

“A Sea of Troubles” (1914; in The Man With Two Left Feet, 1917)

I had forgotten to warn Jeeves about the beard, and it came on him absolutely out of a blue sky.

“Comrade Bingo” (1922; in The Inimitable Jeeves, 1923)

“The whole affair was the most ghastly shock to me. It came absolutely out of a blue sky.”

“No Wedding Bells for Him” (1923; in Ukridge, 1924)

This stupendous stroke of luck, coming so unexpectedly out of a blue sky, had for a moment almost unmanned Percy Pilbeam.

Bill the Conqueror, ch. 9.1 (or ch. 11.1 of magazine serial) (1924)

Mark you, I had been heaved out of the old home by my Aunt Julia many a time before, so it wasn’t as if I wasn’t used to it; but I had never got the boot quite so suddenly before and so completely out of a blue sky.

“A Bit of Luck for Mabel” (1925; in Eggs, Beans and Crumpets, 1940)

“And then this happens—out of a blue sky, as you might say.”

“Pig-hoo-o-o-o-ey!” (1927; in Blandings Castle and Elsewhere, 1935)

“But one morning, out of a blue sky, I’m darned if my secretary didn’t come in and inform me that he was her nephew and had been left this mine.”

Big Money, ch. 8 (1931)

He seemed to remember a similar thing having happened to the Israelites in the desert … and then suddenly out of a blue sky all the manna they could do with and enough over for breakfast next day.

“The Knightly Quest of Mervyn” (in Mulliner Nights, 1933; originally published as “Quest” in Strand magazine, 1931)

“ ‘I see that girl Dolly Henderson who used to be at the Tivoli has got married,’ he said. Out of a blue sky . . .”

Heavy Weather, ch. 10 (1933)

Well, I mean to say, when a girl suddenly asks you out of a blue sky if you don’t sometimes feel that the stars are God’s daisy-chain, you begin to think a bit.

Right Ho, Jeeves, ch. 1 (1934)

At this difficult point in my affairs, what should happen but out of a blue sky the odd-job man at The Cedars handed in his portfolio for some reason or other, and my aunt told me to go to the Employment agency and enrol a successor.

“The Come-Back of Battling Billson” (1935; in Lord Emsworth and Others, 1937)

For this telegram, this brief telegram, this curt, cold, casual telegram which had descended upon him out of a blue sky was from the girl he loved.

The Luck of the Bodkins, ch. 1.4 (1935)

But you never know. You form your schemes and run them over in your mind and you can’t see a flaw in them, and then something happens out of a blue sky which dishes them completely.

“Trouble Down at Tudsleigh” (1935; in Young Men in Spats, UK edition, 1936)

In either case, you didn’t get results casually like this—out of a blue sky, as it were.

Laughing Gas, ch. 7 (1936)

“One morning, out of a blue sky, what do you think? She sprang it on me that she wanted me to marry a certain wench of means, a girl I particularly disliked.”

Summer Moonshine, ch. 5 (1937)

“And then, out of a blue sky, they sprang it on me that I would have to make a speech at the wedding breakfast—to an audience, as I said before, of which Roderick Spode and Sir Watkyn Bassett would form a part.”

The Code of the Woosters, ch. 3 (1938)

His original play was one of those sixty-or-seventy-performances things, and he must have written it off as a complete loss. And then out of a blue sky it becomes a gold mine, for he can’t be getting less than one per cent of the gross, more probably two.

Letter to Bill Townend, dated May 15, 1947, in Performing Flea (1953)

That way of composition is much easier, but the trouble is you have to have the ‘scene’, and it is not often that ‘scenes’ drop out of a blue sky.

Letter to Mr. Summers, August 12, 1947, in P. G. Wodehouse: A Life in Letters (2011)

The invalid started, as any man might on finding so substantial a touch coming out of a blue sky.

Spring Fever, ch. 4 (1948)

“One day, out of a blue sky, you get a little unexpected money. What do you do? You say to yourself that now is your chance to buy some Paris clothes and have a holiday in France. Ah, la belle France!”

French Leave, ch. 10.4 (1956)

And at the same time I spotted the flaw in this scheme I had undertaken to sit in on—viz. that you can’t just charge into a room and start calling someone names—out of a blue sky, as it were—you have to lead up to the thing.

Jeeves in the Offing/How Right You Are, Jeeves, ch. 16 (1960)

At the outset he had been all joy and effervescence, feeling that out of a blue sky Fate had handed him the most stupendous bit of goose and that all was for the best in this best of all possible worlds, but as the time went by doubts began to creep in.

Ice in the Bedroom, ch. 2 (1961)

A silly thing to do, of course, to gasp like that, but, dash it, if for years you have nursed a gentleman’s personal gentleman in your bosom and out of a blue sky you find that he has deliberately sicked Brazilian explorers on to you, I maintain that you’re fully entitled to behave like a dog in the throes of nausea.

Stiff Upper Lip, Jeeves, ch. 20 (1963)

“Joe Cardinal has fallen in love with a girl, and before he’d had time to start pressing his suit he finds she’s sailing on the Atlantic on Thursday. A nice bit of news for him to get out of a blue sky, you’ll admit.”

“Life with Freddie” (in Plum Pie, 1966/67)

Bronx cheer (ch. 1.3, p. 16) °

Rude noise made by blowing through closed lips: US equivalent of raspberry. The OED records the first use in print as 1929, but Google Books finds a 1923 example from Time magazine. Wodehouse’s example is probably the first use in a figurative sense. Wodehouse also seems to have invented the use of raspberry to mean a dismissal; see A Damsel in Distress.

Even Stephen (ch. 1.3, p. 16) *

Slang for “equal shares” or “fifty-fifty.” OED has citations, mostly from the US, dating to the mid-nineteenth century, some spelled “Steven” and some in lower case. Wodehouse’s usage in Sam the Sudden is among the OED citations, and he also used it in Money in the Bank.

beazel (ch. 1.3, p. 16) °

Mark Hodson’s original comment was:

This is very obscure – it clearly means ‘woman’ (as it also does on p. 145 below), but so far it has not been possible to find an independent record of it elsewhere – not even in the OED.

Jonathon Green’s online Dictionary of Slang has long had a couple of 1920s references to beasel meaning “flapper, girl.” Since the earlier update of these notes in 2020, Green has included this sentence from Wodehouse. This sentence seems to be Wodehouse’s first use of this spelling. [The sentence was omitted from the US magazine serial.]

See also the earlier spelling beazle in “Came the Dawn” (1927) and the annotation in Meet Mr. Mulliner.

...stick up men are not quite (ch. 1.3, p. 16)

Not quite gentlemen – cf. Trollope, Last Chronicle of Barset (1867): “Still he wasn’t quite,—not quite, you know—‘not quite so much of a gentleman as I am’—Mr. Walker would have said, had he spoken out freely that which he insinuated. But he contented himself with the emphasis he put upon the ‘not quite’, which expressed his meaning fully.”

“Chatty-o” (ch. 1.3, p. 16) *

As always, Wodehouse’s ear for mispronunciation was acute. Surely when living in France he had heard American tourists bungle the pronunciation of Château.

“I’ll bet she’s got ice.” (ch. 1.3, p. 16) *

See Leave It to Psmith.

inside stand (ch. 1.3, p. 17)

Wodehouse seems to have been the first to use this expression in print. It was also the title of the stage version of Hot Water, first produced in 1935.

industrial depression (ch. 1.3, p. 17) *

This seems to be Wodehouse’s first reference in fiction to the economic slump of the 1930s; here he wryly applies it to the slimmer pickings of crime as well.

“Johnny Bingley has just been in to see me.”

“If he wants a raise of salary, talk about the Depression.”

“The Nodder” (1933; in Blandings Castle and Elsewhere, 1935)

An urgent, tear-compelling note had now succeeded the note of hope in his voice. It was the same one he was wont to employ when trying to persuade the personnel of the studio to take a cut owing to the depression.

The Luck of the Bodkins, ch. 5 (UK edition only, 1935)

“Say, listen,” said, Mr. Llewellyn, with a quaver in his voice, “. . . there’s a depression on . . . and things don’t look any too good in the picture business . . .”

The Luck of the Bodkins, ch. 27 (1935)

“I was on a Los Angeles paper. But the depression has upset everything. They let me go.”

Laughing Gas, ch. 4 (1936)

He recalled now that Miss Gwenda Gray, star author on his list, was sailing for America today to add one more to the long roll of English lecturers who have done so much to keep the depression going in that unfortunate country…

Summer Moonshine, ch. 3 (1937)

In a letter to his friend Bill Townend, writing from Hollywood in 1930:

There is great business depression over here. Movies are doing terribly badly and miniature golf-courses have bust up altogether.

Quoted in P. G. Wodehouse: A Life in Letters, ed. Sophie Ratcliffe, dated October 28, 1930

For the meteorological phenomenon usually called a V-shaped depression, see Summer Lightning and the further links at that note.

automatic (ch. 1.3, p. 17)

The use of the word “automatic” on its own for an automatic (i.e. self-loading) pistol seems to have originated in the US around 1900. The OED cites a Sears catalogue of 1902.

dough (ch. 1.4, p. 17)

The use of “dough” as slang for money goes back at least to the mid-19th century in the US.

Byronic despair (ch. 1.4, p. 18) *

Wodehouse’s references to George Gordon, Lord Byron, are frequent. His soulful passionateness and his romantic beauty are often mentioned. Allusions relating to his moodiness include the following:

“You’ve soured my life,” said his lordship, frowning a tense, Byronic frown.

A Gentleman of Leisure/The Intrusion of Jimmy, ch. 27 (1910)

He reached for a cigarette, opened his case, and found it empty. He uttered a mirthless, Byronic laugh.

Jill the Reckless/The Little Warrior, ch. 20.2 (1920)

The cloud had passed from his face, the look of Byronic despair from his eyes.

Ronnie Fish in Summer Lightning, ch. 2 (1929)

“How are you feeling now? I have just passed through one of those Byronic spells, caused principally by two days rain.”

Letter to Will Cuppy, dated April 29, 1931, from Beverly Hills, Cal., in P. G. Wodehouse: A Life in Letters.

Tubby, on his side, clenched his fists and drew in his breath with a sharp hiss, his face the while taking on a Byronic gloom.

Summer Moonshine, ch. 1 (1937)

For it was just then that the figures in the tapestries on the walls noted that a strange silence had fallen upon the young master of the revels and that he refused the entrée in a manner that can only be described as Byronic. Something, it was clear, had suddenly gone amiss with Tipton Plimsoll.

Full Moon, ch. 4.2 (1947)

I had seen him around the place, of course, but always in the company of a brace of assorted aunts or that of his cousin Gertrude, in each case looking Byronic. (Checking up with Jeeves, I find that that is the word all right. Apparently it means looking like the late Lord Byron, who was a gloomy sort of bird, taking things the hard way.)

The Mating Season, ch. 19 (1949)

It was a somber, Byronic Barmy, a Barmy with a heart bowed down with weight of woe and a soul with blisters on it, who at eight o’clock that night presented himself at the door of Mervyn Potter’s apartment.

Barmy in Wonderland/Angel Cake, ch. 5 (1952)

Mrs. Spottsworth was surprised. On the rustic seat just now, especially in the moments following the disappearance of her pendant, she had found her host’s mood markedly on the Byronic side.

Ring for Jeeves/The Return of Jeeves, ch. 14 (1953/54)

Naturally pig lovers like their pigs to look on the bright side—a pig that goes about wrapped in a sort of Byronic gloom can cast a shadow on the happiest farm—but one does not want them getting over-familiar with strangers and telling long stories without any point.

“America Day by Day” in Punch, August 22, 1956; adapted similarly into Over Seventy, ch. 15 (1957)

not even lunch-money (ch. 1.4, p. 18) *

Lunch money here refers to a trivial sum, in an American context related to the provision of hot lunches in school cafeterias. Students were asked to bring a few cents in payment to avoid it appearing to be dependence upon charity; the amount was usually calculated to be affordable for all, with the rest of the cost subsidized by the school.

This seems to be the only use of the term in Wodehouse’s fiction.

Pale hands I loved beside the Shalimar (ch. 1.4, p. 18) °

Number 3 of the collection ‘Four Indian Love Lyrics’ by ‘Laurence Hope’ (pen name of Violet Adela Florence Nicolson, 1865–1904). Set to music by Amy Woodforde-Finden, 1902. The poem originally appeared in The Garden of Káma, 1901; it is not a translation. Wodehouse also mentions another song from the collection, ‘Less than the dust...’ in several books.

Pale hands I loved beside the Shalimar,

Where are you now? Who lies beneath your spell?

Whom do you lead on rapture’s roadway far,

Before you agonise them in farewell?

Oh, pale dispensers of my Joys and Pains,

Holding the doors of Heaven and Hell,

How the hot blood rushed wildly through the veins,

Beneath your touch, until you waved farewell.

Pale hands, pink tipped, like Lotus buds that float

On those cool waters where we used to dwell,

I would have rather felt you round my throat,

Crushing out life, than waving me farewell.

Laurence Hope & Amy Woodforde-Finden: Kashmiri Song

Wodehouse referred to it in other books, most memorably in Bertie’s opening narration of Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit:

As I sat in the bath-tub, soaping a meditative foot and singing, if I remember correctly, “Pale Hands I Loved Beside the Shalimar,” it would be deceiving my public to say that I was feeling boomps-a-daisy.

Captain Biggar sings it in Ring for Jeeves; Galahad recalls the danger of reading the poem with a girl in Galahad at Blandings.

Michelangelo (ch. 1.4, p. 19)

The Florentine artist Michelangelo di Buonarroti (1475–1564) was famous as a sculptor, architect, and poet as well as being a painter.

copped off the widow (ch. 1.4, p. 19) *

The OED has American citations for forms of to cop off in the sense of taking something for oneself, especially dishonestly, dating back to 1887 when a Boston paper defined the work of a confidence man as “copping off stuff.”

So Keeler got home, or, as the writer puts it, “copped off his little rim,” and Fultz meanwhile “flipflapped to second under the circumstances.”

“Baseball” (1904)

“I know you think you’ve been given a raw deal, Kirk chipping in like that and copping off Miss Ruth, but, for the love of Mike, what does it matter?”

The White Hope/The Coming of Bill, ch. 9 (1914/20)

the big crash (ch. 1.4, p. 19) °

The American stock market had collapsed in October 1929, marking the start of a world-wide economic recession known as the Great Depression.

Electric Bond and Share was a subsidiary of General Electric, set up in 1905 to buy up local electric power and streetcar companies. Its stock price closed at 183 on September 3, 1929 (just as an example; this may not have been the peak) and traded as low as 50 in late October (again, this may not have been the minimum).

Aaron Montgomery Ward (1844–1913), a former employee of the Chicago store Marshall Field, established the world’s first mail-order business in 1872. Starting in 1926, they also opened a chain of department stores (for which the character “Rudolph the red-nosed reindeer” was created in 1939). The company was taken over by GE and declared bankruptcy early in 2001. In 1929, Montgomery Ward stock had hit a high of $156 per share, but dropped from $84 to $50 in a single day of trading on Black Thursday, October 24.

Hot zig! (ch. 1.4, p. 19) *

Apparently a variant form of hot ziggety, an enthusiastic interjection first recorded in U.S. usage in the 1920s. The OED has a 1933 citation for Hot ziggety zig!; I have submitted this earlier, shorter form to the dictionary. [NM]

going down in an express elevator (ch. 1.4, p. 19) *

It would be more accurate to say that Baxter felt like a man taking his first ride in an express elevator, who has outstripped his vital organs by several floors and sees no immediate prospect of their ever catching up with him again.

Something New/Something Fresh, ch. 8 (1915)

He was conscious of a feeling which he had only experienced twice in his life—once when he had taken his first lesson in driving a motor and had trodden on the accelerator instead of the brake; the second time more recently, when he had made his first down-trip on an express lift.

“Doing Father a Bit of Good” (1920; in Indiscretions of Archie, ch. 10, 1921)

It was the first time that he had seen Eunice Bray, and, like most men who saw her for the first time, he experienced the sensations of one in an express elevator at the tenth floor going down who has left the majority of his internal organs up on the twenty-second.

“The Rough Stuff” (1920; in Golf Without Tears, 1924; with “express lift” in The Clicking of Cuthbert, 1922)

That is what happened to me at this juncture, and a most unpleasant feeling it was—rather like when you take one of those express elevators in New York at the top of the building and discover, on reaching the twenty-seventh floor, that you have carelessly left all your insides up on the thirty-second, and too late now to stop and fetch them back.

“Jeeves and the Kid Clementina” (1930; in Very Good, Jeeves, 1930, this passage in UK editions only)

Cyril was aware of an odd feeling of having been hit by an atom bomb while making a descent in an express elevator.

“Sleepy Time” (1965; in Plum Pie, 1966/67)

And, for the only time so far found about going up rather than down:

“It’s an odd sensation. Much the same as going up in an express elevator and finding at the halfway point that you’ve left all your insides at the third floor.”

Frozen Assets/Biffen’s Millions, ch. 3.2 (1964)

He handed over a hundred francs (ch. 1.4, p. 20) *

In the early 1930s, a hundred francs was approximately equal to four US dollars or £1 3s. sterling. In 2025 terms of buying power, the equivalent would be close to $100.

Patsy (ch. 1.5, p. 20) *

A dupe or scapegoat; the school dunce character in vaudeville skits (Harpo in the Marx Bros’ Fun in Hi Skule). Wodehouse may have learned it from George Ade (three citations in Green’s Dictionary of Slang) or from his friend Marion Davies, who had played the title role in the 1928 film of that title.

squidge (ch. 1.5, p. 20) *

This time the OED finds it twice in George Ade, including a 1907 citation defining it as “the fellow who does all the worrying and gets nothing out of it.” OED also cites Wodehouse linking this with the above term in Performing Flea, p. 205, in the camp diary “Huy Day by Day”:

…the fellow whom Fate has called upon to be the Patsy, the Squidge or, putting it another way, the man who has been left holding the baby.

a bird in a gilded cage (ch. 1.5, p. 20)

Song by Harry Von Tilzer (music) & Arthur J. Lamb (lyric), 1900

The ballroom was filled with fashion’s throng,

It shone with a thousand lights,

And there was a woman who passed along,

The fairest of all the sights!

A girl to her lover then softly sighed:

“There’s riches at her command!”

“But she married for wealth, not for love,” he cried,

“Though she lives in a mansion grand.

“She’s only a bird in a gilded cage,

A beautiful sight to see.

You would think she was happy and free from care,

She’s not, though she seems to be.

’Tis sad when you think of her wasted life,

For Youth cannot mate with Age.

And her beauty was sold

For an old man’s gold.

She’s a bird in a gilded cage.”

Arthur J. Lamb, Harry Von Tilzer: “A Bird in a Gilded Cage”

where men are men (ch. 1.5, p. 20) *

See Leave It to Psmith.

knickerbockers (ch. 1.5, p. 20) *

An American way of referring to knee breeches and stockings rather than trousers. See Uncle Fred in the Springtime regarding court dress.

“Look-ut!” I’ll say (ch. 1.5, p. 22) *

The hyphen is a Penguin mistake; it appears as “Lookut!” in both US and UK first editions here and in ch. 5, although in the UK book it is hyphenated at a page break at this point. In the more common spelling “lookit” it is cited in the OED as chiefly US slang from 1907 on, as an imperative to direct or draw attention. A more formal equivalent might be “Look here!”

“You’re right, that’s Hollywood,” said the patrolman. “Lookit, ma’am. Watch. What’s this?”

The Old Reliable, ch. 16 (1951)

because it’s wet (ch. 1.5, p. 22) *

Both US and UK first editions have “all wet” here, and Penguin reproduces “all wet” in ch. 10.4, p. 136, so its omission here is another mistake.

The phrase means “mistaken, completely wrong”; OED calls it originally and chiefly US colloquial and cites a 1923 definition from the New York Times: “All wet, all wrong.”

air-castles (ch. 1.5, p. 22) *

Imaginary, impossible, visionary projects or dreams. In this form, dating back to the eighteenth century; as “a castle in the air” going back at least to Christopher Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus. Wodehouse had written the lyric to Jerome Kern’s music for the song “My Castle in the Air” from Miss Springtime (1916).

ten thousand (ch. 1.5, p. 22) *

A simple consumer-price-index conversion factor from 1932 to 2025 would be to multiply by 25, so this would be a quarter of a million dollars in modern purchasing power. For other comparisons including issues such as the cost of labor, the multiplier would be even greater.

Sixty grand ... good gravy ... fish (ch. 1.5, p. 23) °

Grand to mean a thousand dollars seems to be early 20th century US slang. Nowadays it also appears in British English to mean a thousand pounds.

This is the first recorded use of good gravy for wealth: gravy by itself to mean money also seems to be early 20th century US slang.

fish as US slang for dollars seems to date from the 1920s. It appears

to be quite rare – possibly Broadway slang.

——Green’s Dictionary of Slang has a 1919 reference as well as one from 1886 for “white fish” for a silver dollar coin. Green also notes that Wodehouse used this American slang in The Mating Season with reference to British pounds, probably uniquely.

Promised Land (ch. 1.5, p. 24) °

In Deuteronomy 34, Moses was shown the Promised Land from the summit of Mount Pisgah, but not allowed to enter it:

1 And Moses went up from the plains of Moab unto the mountain of Nebo,

to the top of Pisgah, that is over against Jericho: and the Lord showed

him all the land of Gilead, unto Dan,

2 and all Naphtali, and the land of Ephraim, and Manasseh, and all the

land of Judah, unto the utmost sea,

3 and the south, and the plain of the valley of Jericho, the city of palm

trees, unto Zoar.

4 And the Lord said unto him, This is the land which I sware unto Abraham,

unto Isaac, and unto Jacob, saying, I will

give it unto thy seed: I have caused thee to see it with thine eyes, but

thou shalt not go over thither.

5 So Moses the servant of the Lord died there in the land of Moab, according

to the word of the Lord.

Bible: Deuteronomy 34:1–5

See also Biblia Wodehousiana.

the sun smiling through (ch. 1.5, p. 24)

A phrase from an often-quoted song lyric: see Meet Mr. Mulliner.

Archimedes ... Eureka (ch. 1.5, p. 24)

Archimedes (?287–212 BCE). Trying to solve the problem of discovering whether a crown belonging to his patron Hieron II of Syracuse was really made of gold, he discovered what is now known as Archimedes’ Principle, that a body immersed in a fluid experiences a buoyant force that is equal to the weight of the fluid displaced. Eureka (more properly “Heureka”) past tense of heurisko (I find), is Greek for “I have found it.”

sitting pretty (ch. 1.6, p. 24) *

See Sam the Sudden.

in the bag (ch. 1.6, p. 24) *

Originally 1920s US sporting slang for a certain or assured victory. The OED cites this sentence from Wodehouse for the sense “as good as in one’s possession.” Derived from the actual bag in which a hunter would carry the game he had shot; while aiming at a bird or animal he might say “it’s in the bag” to express his confidence that it might as well already be there, that he will be carrying it home.

pete (ch. 1.6, p. 25)

Safe – twentieth century American slang, but it comes from the old thieves’ cant word “peter” meaning a trunk or portmanteau, which goes back to the late 17th century.

not handing myself a thing (ch. 1.6, p. 25) *

Not giving myself undue credit; not bragging.

On account she wants (ch. 1.6, p. 25) *

Colloquial for Because she wants. Wodehouse uses on account without of in this sense as a marker for American speech. An incomplete list:

“When I tried for a job at the Colossal-Exquisite last spring I was turned down on account you said I had no sex-appeal.”

Sergeant Donahue of Beverly Hills in “The Rise of Minna Nordstrom” (1933; in Blandings Castle and Elsewhere, 1935)

“There was this guy Elmer B. Zagorin—the Night Club King, they used to call him, on account he ran a chain of night clubs in all the big cities—had fifty million dollars and refused to pay a bill for forty for hair restorer.”

Sam Bulpitt in Summer Moonshine, ch. 14 (1937); the first of three usages in this book

“We had to break off the conference just then, on account there was a guy she wanted to see indoors, but it’s all fixed.”

Soapy Molloy in Money in the Bank, ch. 10 (1942); the first of several such usages by Soapy and Dolly in the book

“He tried for a job at Medulla-Oblongata-Glutz last week, and they turned him down on account he wanted to do whimsical comedy and they said he wasn’t right for whimsical comedy.”

Sergeant Ward of Beverly Hills in The Old Reliable, ch. 16 (1951)

“She’s climbing up an apple tree. On account she’s in high spirits,” explained Mr. Lehman.

Barmy in Wonderland, ch. 9 (1952)

“He was in London, see, on account he couldn’t get over for the opening, and he cabled Charlie.…”

American doorman quoted in Bring On the Girls, ch. 1.4 (1953/54)

string the beads (ch. 1.6, p. 25)

Tell a story; possibly an allusion to the Rosary, or to this:

Can string you names of districts, cities, towns,

The whole world over, tight as beads of dew

Upon a gossamer thread;

Wordsworth: Prelude V, 320–322

Chapter 2

Sunshine … turned the pavements to gold. (ch. 2.1, p. 26) *

Wodehouse had earlier alluded to Shakespeare’s patines of bright gold in a similar passage in Bill the Conqueror, ch. 10.1, about the sunlit pavement in front of Tilbury House. One wonders why he missed out on the reference here.

costermongers (ch. 2.1, p. 26)

People who sell fruit and vegetables in London streets (from the old word “costard” an apple)

dray-horses (ch. 2.1, p. 26)

Horses were still commonly used for moving goods in British cities until after the second world war. A dray is a low-sided cart, typically used by brewers.

Waterloo station (ch. 2.1, p. 26) °

Waterloo station is a London railway terminus located just south of the river Thames. It was opened in 1848 to serve the London and Southampton Railway Company’s line to Southampton. This company later became part of the London and South Western Railway, and from 1923 the Southern Railway. The old Waterloo was famously chaotic, comprising at least four separate stations that had grown together over the years; Wodehouse commented on its confusion in the 1909 version of Love Among the Chickens, ch. 3. The LSWR rebuilt it completely to something like its modern form in 1922. The station serves much of the South-West of England, including the seaside resorts of Hampshire, Dorset and Devon. It was also, of course, the terminus for boat trains to the port of Southampton (cf. p.31 below).

Xenophon’s ten thousand (ch. 2.1, p. 26)

In 401 BCE, the Persian king Artaxerxes defeated his brother Cyrus at the battle of Cunaxa, on the Euphrates. Cyrus’s force included ten thousand Greek mercenaries, led by the Athenian general and historian Xenophon. He describes their retreat to the Black Sea in his book Anabasis. There is a famous moment when after a long journey through the mountains they first catch sight of the sea from the top of a mountain and cry out “thalassa, thalassa” (the sea, the sea!).

Yeovil and points west (ch. 2.1, p. 26) °

Yeovil in Somerset was an important junction, about a hundred miles from London, through which anyone heading for Devon or beyond by the LSWR route would have to pass. It is one of the stops on Ukridge and Jeremy Garnet’s train in Love Among the Chickens.

Beatrice Bracken … Earl of Stableford … Patrick B. Franklyn (ch. 2.1, p. 27) °

It is probably too early for Beatrice’s surname to be a conscious allusion to the Irish-born politician and newspaper proprietor Brendan Bracken (1901–1958). In Wodehouse terms, her polysyllabic first name marks her out immediately as an unsuitable fiancée who will insist on moulding her young man. Bracken is an Irish name (Ó Breacáin – from breac, meaning speckled); in English, the plant is something generally deprecated by landowners (poisonous to sheep, takes over whole hillsides....).

Her father’s title is named after the Shropshire hamlet where Wodehouse’s parents lived from 1895 to 1902.

A franklin is a freeman or freeholder, which is perhaps relevant to Packy as he is unusual in being a muscular Wodehouse hero who is also reasonably well-provided with money. ‘Packy’ also does not fit into the usual pattern of muscular Joes, Sams, and Bills and silly Berties, Freddies, and Pongos. (cf. Usborne for a discussion of Wodehouse’s use of given names.)

Is there any significance in the fact that Beatrice has an Irish family name and Packy an Irish first name, I wonder?

For the significance of the middle initial in Packy’s full name, see Money for Nothing.

Worbles ... Biddlecombe (ch. 2.1, p. 27)

Both fictitious. Many place names in Somerset and North Devon end in -combe (a hollow, or small valley, cf. Welsh cwm). Biddlecombe is perhaps an amalgam of Bideford and Ilfracombe. Hunt Balls, given by the local foxhunt, are among the most important county social events.

Ascot ... Lord’s (ch. 2.1, p. 27) °

Ascot races in Berkshire take place in mid-June. Access to the Royal Enclosure is by invitation of the King or Queen, so this is one of the most exclusive social events of the year.

The Eton and Harrow cricket match has been played at Lord’s Cricket Ground in London since 1805, when Lord Byron was in the Harrow team. It also takes place in June.

Jacquerie ... facile princeps ... ne plus ultra ... crêpe royale (ch. 2.1, p. 27) °

Jacquerie is a collective term for peasants, deriving from a peasants’ revolt in northern France in 1358.

facile princeps (Latin) – acknowledged leader (literally easily chief)

ne plus ultra (Latin) – “nothing further beyond,” “go no further” (the words said to have been inscribed on the Pillars of Hercules). Normally means, as here, the acme or point of highest achievement. [Both US and UK first editions have the variant form non plus ultra here, with apparently identical meaning. —NM]

crêpe royale – Crêpe or crape is a fabric, usually real or imitation silk, treated with a mechanical embossing process to give it a crinkled surface. (A crêpe royale in the culinary sense is a dessert crêpe [i.e. thin pancake] with chocolate sauce, bananas and strawberries. It is entirely possible that Wodehouse is pulling our legs with nonsensical dressmaking terms here.)

To cut on the bias is to cut diagonally, across the texture of the fabric. The close-fitting dresses made famous by Jean Harlow are a good example of this technique.

Fireside Chatter seems to be fictitious, but sounds rather like the name of the periodical run by Charles Dickens, Household Words.

tripper season (ch. 2.1, p. 27) *

Though tripper as a colloquial term for one who takes a journey for pleasure is cited in the OED as early as 1813, the first appearence of tripper season in the Google Books corpus is from 1892.

petrol at its current price (ch. 2.1, p. 27) *

The US magazine serial and book both say “gasoline” here, of course. Petrol retailed in the UK in 1932 for a shilling and 4½ pence per imperial gallon [4.546 liters] before a threepence per gallon increase in September 1932. This report suggests it works out to about the equivalent of £1.10 per liter adjusted to 2017 for inflation.

US gasoline prices were about 18 cents per US gallon in 1932, which would adjust for inflation to $2.65 in 2018 values.

Lazlo portrait (ch. 2.1, p. 27) °

László, Philip de (1869–1937) – Hungarian-born portrait painter (and occasional sculptor) who settled in London in 1907 and became a British citizen in 1914. He painted many Edwardian worthies and members of the aristocracy: Thirteen of his portraits are in the NPG in London.

Only the US book spells his name as Laszlo, though without the accent marks.

bulldog breed (ch. 2.1, p. 28) *

See Money for Nothing.

Sealyham (ch. 2.1, p. 28) °

A breed of small terrier, originally developed for otter hunting by Captain John Owen Tucker-Edwardes in Pembrokeshire, and recognised by the Kennel Club in 1910. Wodehouse’s fellow writer Dornford Yates was associated with Sealyhams in much the same way that Wodehouse was associated with Pekes. The best-known Sealyham in Wodehouse is Flick Sheridan’s beloved Bob in Bill the Conqueror; see Bill the Conqueror for more.

port ... starboard (ch. 2.1, p. 28)

Nautical terms for the left and right sides of a ship, seen in the direction of travel. Wodehouse is planting the idea that Packy is a yachtsman.

modern suggestiveness (ch. 2.1, p. 28) *

See Money for Nothing.

Parker (ch. 2.1, p. 28) °

One of Wodehouse’s favourite names for minor characters. The third edition of Who’s Who in Wodehouse lists eighteen. Wodehouse worked alongside Dorothy Parker on Vanity Fair from autumn 1917 to April 1918, and claimed to have disliked her so intently that he had expunged her from his mind (Phelps, p.118).

Blair Eggleston’s Worm i’ the Root (ch. 2.1, p. 28) °

In Eggleston’s literary pretensions, Wodehouse is probably mocking modernist writers of the time like Percy Wyndham Lewis (1882–1957) and his imitators, who specialised in bleak, satirical works. Lewis himself would be too old to be Eggleston, of course. In Chapter 8, Eggleston is described as a Bloomsbury novelist, though again most of the Bloomsbury set were of Wodehouse’s own generation rather than Eggleston’s.

It has also been suggested that the name Blair might be an allusion to George Orwell (Eric Blair), though this seems unlikely as Orwell’s first important book, Down and Out in Paris and London, only appeared in 1933, after the publication of Hot Water. Moreover, Orwell may have been an intellectual, but he was also a competent professional writer, something Wodehouse would have respected even before Orwell went to Wodehouse’s defence over his wartime broadcasts from Germany.

The village of Egglestone and its medieval abbey lie in County Durham, near Barnard Castle.

Wodehouse is having fun with us, because although Worm i’ the Root sounds even bleaker than “worm i’th’bud,” there is of course nothing at all sinister or unusual about a worm in a root: Egglestone’s modification takes away all the force of Shakespeare’s image.

The title, of course, is an allusion to Shakespeare:

She never told her love,

But let concealment, like a worm i’th’bud,

Feed on her damask cheek.

Shakespeare: Twelfth Night II:iv

See Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse for more Wodehouse usages of the passage.

side whiskers (ch. 2.1, p. 28) *

See Blandings Castle and Elsewhere.

Edgar Wallace (ch. 2.1, p. 28)

Edgar Wallace (1875–1932). Wallace was even more prolific than Wodehouse – his 173 novels in many different genres (science-fiction, crime, colonial adventure...) sold more than 50 million copies worldwide. Packy’s claim to have read all of them is perhaps a little unlikely, but not impossible. Wodehouse was an enthusiast, and dedicated Sam the Sudden (1925) to him.

Yahoo (ch. 2.1, p. 28)

In Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (1726), the Yahoos were debased, brutish, human-like creatures subservient to the noble, horse-like Houyhnhnms.

get behind his spiritual self and push (ch. 2.1, p. 29) *

See Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit.

Yale (ch. 2.1, p. 29) *

One of the Ivy League universities, founded in New Haven, Connecticut, in 1701.

Other Yale graduates in Wodehouse include Jimmy Pitt, according to the American versions of The Intrusion of Jimmy, and Bill Brewster in Indiscretions of Archie. The Duke of Dunstable isn’t sure whether Wilbur Trout played football for Harvard or for Yale in A Pelican at Blandings. John Maude at Harvard in the US version of The Prince and Betty, Bill West at Harvard in Bill the Conqueror, and Freddie “Butch” Carpenter at Princeton in French Leave had played football against Yale teams. Bradbury Fisher in “Keeping In with Vosper” pretends that he will be attending a Sing-Sing vs. Yale football match.

given it the short end (ch. 2.1, p. 29) *

The “short end” is US slang for a lesser share, a losing part of a deal; the OED cites it from George Ade in 1904.

missing … on several cylinders (ch. 2.1, p. 29) *

Compared to an automobile engine running roughly if at all; see Thank You, Jeeves.

sold short (ch. 2.1, p. 29) *

Earlier citations in the OED for the phrase to sell short are all in the financial sense: selling a stock that one does not yet own, in the anticipation of a drop in price so that one can buy it more cheaply than the sales price. In the figurative sense of “to belittle; to undervalue” the earliest citation is from 1936. I have submitted this earlier usage to the OED. [NM 2025-06-20]

James, the footman (ch. 2.1, p. 29) *

Servants such as footmen often were called by names not their own, as if they were taking on roles in a play; the first footman might always be called Charles and the second footman James, even if new servants were placed in these positions. This not only saved their employers the trouble of remembering real names, but tended to remind the servants of their status.

Excelsior (ch. 2.1, p. 29)

The shades of night were falling fast,

As through an Alpine village passed

A youth, who bore, ’mid snow and ice,

A banner with the strange device,

Excelsior!

His brow was sad; his eye beneath,

Flashed like a falchion from its sheath,

And like a silver clarion rung

The accents of that unknown tongue,

Excelsior!

In happy homes he saw the light

Of household fires gleam warm and bright;

Above, the spectral glaciers shone,

And from his lips escaped a groan,

Excelsior!

“Try not the Pass!” the old man said;

“Dark lowers the tempest overhead,

The roaring torrent is deep and wide!”

And loud that clarion voice replied,

Excelsior!

“Oh, stay,” the maiden said, “and rest

Thy weary head upon this breast!”

A tear stood in his bright blue eye,

But still he answered, with a sigh,

Excelsior!

“Beware the pine-tree’s withered branch!

Beware the awful avalanche!”

This was the peasant’s last Good-night,

A voice replied, far up the height,

Excelsior!

At break of day, as heavenward

The pious monks of Saint Bernard

Uttered the oft-repeated prayer,

A voice cried through the startled air,

Excelsior!

A traveller, by the faithful hound,

Half-buried in the snow was found,

Still grasping in his hand of ice

That banner with the strange device,

Excelsior!

There, in the twilight cold and gray,

Lifeless, but beautiful, he lay,

And from the sky, serene and far,

A voice fell, like a falling star,

Excelsior!

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow: Excelsior

a couple of other fellows (ch. 2.1, p. 29) *

See Summer Lightning.

auxiliary yawl ... (ch. 2.1, p. 30)

A yawl is a small sailing boat with a mainmast and a jigger (i.e. a small mizzen mast placed close to the stern). Auxiliary means that it is also fitted with an engine. With Marconi rig (also known as Bermuda rig) the mainsail is triangular and there is no need for a gaff. A 45ft (13m) yacht normally has room for four or five people, but would not be too big to manage single-handed.

with three eyes (ch. 2.1, p. 30) *

A Penguin misprint; all original editions have “with green eyes” here.

en brosse (ch. 2.1, p. 30) *

French for “in the form of a brush”; cut short, as in a military cut or crew cut, so that the hair stands up as in the bristles of a brush.

a sealed book (ch. 2.1, p. 30) *

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

County (ch. 2.1, p. 31) *

Especially when capitalized, as here, this is short for the local gentry, the upper-class families who constitute Society in the neighborhood. [Omitted from US magazine serial.]

made whoopee (ch. 2.1, p. 31) *

From the exuberant exclamation “Whoopee!” recorded in the US in 1862 and in Kipling in 1890, the phrase was coined for the 1928 song “Makin’ Whoopee” by Gus Kahn (lyrics) and Walter Donaldson (music), popularized by Eddie Cantor in the 1928 musical “Whoopee!” and the 1929 film based on it. The song emphasizes the amorous side of the phrase’s meaning, but other OED citations are more in line with Wodehouse’s usage here, emphasizing exuberant partying and drinking and rowdiness.

paint the old town pink (ch. 2.1, p. 31) *

Paint the town red is the more idiomatic phrase in US English, going back to 1882; Wodehouse is having fun with the Vicomte’s partial fluency in the language. James Joyce had used “painted the town tolerably pink” in Ulysees (1922) but it seems unlikely that Wodehouse would have sought out that book.

farceur ... speakeasy (ch. 2.1, p. 31) °

A farceur is a joker, a buffoon – the word has even been borrowed into English from French. A speakeasy is an unlicensed drinking establishment. The term was particularly used in the US during Prohibition, but goes back at least to the 1880s.

Southampton (ch. 2.1, p. 31) *

A typical point of departure for ships crossing the English channel to Brittany. Trains on the South Western railway line would depart from Waterloo several times a day for Southampton and points beyond.

If taking the shorter Dover–Calais Channel crossing, that boat train would leave from Victoria Station, not Waterloo.Zut! (ch. 2.1, p. 32) *

A mild French imprecation, roughly equivalent to “Damn!” or “Blast!”

Northumberland Hotel (ch. 2.1, p. 33)

The Northumberland Hotel was a small hotel, close to Charing Cross Station, which famously appeared in The Hound of the Baskervilles as the place where Sir Henry Baskerville stayed in London. It is now the Sherlock Holmes pub. It would have been far too small to be the hotel meant here – a better bet would be the Savoy, which is also just across the river from Waterloo.

“get into hot water of some kind” (ch. 2.1, p. 33) *

Wodehouse often took the title of his novels from some phrase within, or (if the case arose) may have inserted it into the text after choosing the title. This is the sole use of the phrase “hot water” in the current book.

flippertygibbet (ch. 2.1, p. 33) °

A restless or chattering person. Cf. Bishop Latimer’s 2nd Sermon before Edward VI (1549): “These flybbergybes an other daye shall come & clawe you by the backe and say [...].” Nowadays more usually written “flibbertygibbet”, corresponding to the name of a character in Scott’s Kenilworth. The US first edition has the spelling “flibbertigibbet”—apparently a change by the Doubleday editor, as the US magazine serial agrees with the UK texts here.

... cashier named Bodkin (ch. 2.1, p. 33) °

Monty Bodkin made his first appearance the following year in Heavy Weather, but Wodehouse had used the surname previously as well: Aubrey Bodkin in “How Kid Brady Joined the Press” (1906) and Harold Bodkin in “The Test Case” (1915).

Yascha Pryzsky ... Queen’s Hall (ch. 2.1, p. 34)

Perhaps an echo of Jascha Heifetz (1901–1987), Russian-born violinist, moved to the USA in 1917. The Queen’s Hall in Langham Place was London’s main large concert hall from its opening in 1893. It was destroyed by bombs in 1941.

Gate Theatre (ch. 2.1, p. 34) °

Mark Hodson’s original note: “Not the modern studio theatre of that name in Notting Hill Gate, although it would fit very well, as that has only been around since 1979. Given Packy’s known propensities, Beatrice can hardly be contemplating letting him loose in Dublin, where the famous Gate Theatre had opened in 1928.”

Wodehouse is probably referring to the Gate Theatre Studio, an independent theatre opened in 1927 on Villiers Street in London after its founders Peter Godfrey and Molly Veness had begun a predecessor in 1925 in Covent Garden. By operating as a theatre club, requiring membership of its patrons, it and other independent theatres could avoid the Lord Chamberlain’s censorship and put on controversial or otherwise uncommercial plays. For instance, the Gate Theatre presented Oscar Wilde’s Salome in 1931. It closed after bomb damage in 1941.

“And day by day in every way I will haunt him more and more.” (ch. 2.1, p. 34) *

Maria Jette reminds us that this is Packy’s variant on the Coué self-improvement maxim “Every day in every way I am getting better and better.” See Leave It to Psmith for more.

“You look like a chrysanthemum” (ch. 2.1, p. 35) *

See Leave It to Psmith for a picture and another humorous non-garden reference to the flower.

Absalom, the son of David (ch. 2.2, p. 35) °

(A shekel is one sixtieth of a mina, which was approximately the same as an English pound, so Absalom’s hair weighed about 3.6 lb or 1.5 kg)

25 ¶ But in all Israel there was none to be so much praised as Absalom

for his beauty: from the sole of his foot even to the crown of his head

there was no blemish in him.

26 And when he polled his head, (for it was at every year’s end that he

polled it; because the hair was heavy on him, therefore he polled it:) he

weighed the hair of his head at two hundred shekels after the king’s weight.

Bible: Samuel 14:25–26

See Biblia Wodehousiana for more.

The US magazine serial and the UK first edition read “Absalom, the son of Saul” here; the US first edition and the Penguin paperback are correct. In general, the US book agrees with the US magazine serial and Penguin follows the UK book text, so in this unusual case, one may speculate that Wodehouse misremembered the Biblical relationship, but that the Doubleday and Penguin editors caught the error and corrected it, while the Collier’s and Jenkins editors did not question Wodehouse’s manuscript. [NM]

caravanserai (ch. 2.2, p. 35)

Originally a Persian term for an inn, especially in the Middle East. Deliberately incongruous here. Assuming it takes five minutes to walk from the platform to the taxi-rank and get a cab, and at least ten minutes to get your hair cut, the hotel must be within ten minutes’ taxi ride of Waterloo station.

the scent of bay-rum (ch. 2.2, p. 35) *

See If I Were You.

lightning strike ... downed scissors (ch. 2.2, p. 36)

A lightning strike is one that is called without any previous warning (first recorded use in the OED is from 1920). The expression “to down tools” is first recorded in 1855 – Wodehouse is having fun at the barbers’ expense by comparing them incongruously to industrial workers.

“Hullo” ... “Are you there?” (ch. 2.2, p. 36) °

The US magazine and both US and UK first edition book texts have the Senator repeat “Hello!”; only the Penguin text alters it to “Hullo!”

Americans conventionally answered the telephone with “Hello” (as recommended by Thomas Edison, as a counter to Alexander Graham Bell’s suggestion of “Ahoy!”). British people habitually answered with “Are you there?” – something Wodehouse often had fun with. Packy is provoking the Voice by replying in the English way even though he himself is American.

the Old Adam (ch. 2.2, p. 36) *

The unreformed or unregenerate self; see Biblia Wodehousiana.

Daily Dozen (ch. 2.2, p. 36) *

Here, figuratively, moral exercises for the strengthening of the soul; an allusion to physical exercises for the body popularized by American coach Walter Camp and often recommended by and practiced by Wodehouse.

Sir Philip Sidney (ch. 2.2, p. 37) °

Sir Philip Sidney (1554–1586), poet, courtier, soldier, known as a model of chivalry. Wodehouse refers to him often, as in Sam the Sudden.

Volstead Act (ch. 2.2, p. 37) °

Andrew Joseph Volstead (1860–1947) introduced this act for the enforcement of the 18th Amendment to the US Constitution, prohibiting the sale of alcoholic beverages. The act came into force – over President Wilson’s veto – in 1919. The 18th Amendment was repealed in 1933. The Volstead Act prohibited the sale of anything with more than 0.5% alcohol content, so presumably the Opal Law would have reduced this to 0.0833%. Wodehouse frequently made fun of American hypocrisy over Prohibition.

The US versions read “Opal bill” instead of “Opal law”; it is not clear why the UK editor changed this, as even in British dictionaries “bill” can mean “a draft of a proposed law” (Chambers). [NM]

improved out of all knowledge (ch. 2.2, p. 38) *

That is, improved beyond recognition. Wodehouse used this phrase from 1905 (The Head of Kay’s) through 1957 (Something Fishy/The Butler Did It) at least.

robot (ch. 2.3, p. 39)

The word was only nine years old – it was invented by Karel Capek (1890–1938) for his play R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots) (1920, translated into English in 1923). Capek also wrote a book called ‘The War of the Newts’ that gave offence to Gussie Fink-Nottle.

five on the ninth … four niblick shots (ch. 2.2, p. 40) *

See A Glossary of Golf Terminology on this site for golfing terms.

time seemed to stand still (ch. 2.3, pp. 41–42) *

Compare The Inimitable Jeeves.

the Scotch Express (ch. 2.3, p. 42) *

See The Inimitable Jeeves for the Scotch Express. The US book substitutes the Empire State Express instead: the flagship train of the New York Central and Hudson River Railroad between New York City and Buffalo, in service 1891–1967.

moron (ch. 2.3, p. 42) *

At this point, the word moron was used by psychologists as a technical term for adults whose mental age was that of a child of eight to twelve, who could be trained to carry out some function in society; for more on this, see Stephen Jay Gould, The Mismeasure of Man (1981). Its generic use as a popular term of invective (as in Senator Opal’s tirade here) and the introduction of IQ scores led to its abandonment by scientists.

Notre Dame (ch. 2.3, p. 43) *

For some unknown reason, the US magazine serial and book omit all references to Notre Dame; in ch. 2.4 the touchdown remembered by Jane Opal was scored against Harvard in US editions.

boa-constricter (ch. 2.3, p. 43) *

A Penguin misprint. All original editions spell it “constrictor,” and US editions omit the hyphen. It is one of the few animals whose common name in English is the same as the Latin taxonomic name, Boa constrictor. (I am not counting reduplicated names like Bison bison and Gorilla gorilla.)

side-whiskers ... moustaches (ch. 2.4, p. 43)

As usual in Wodehouse, his facial hair marks Blair out as no good, as if we hadn’t already guessed that from his name and the title of his novel.

wires crossed (ch. 2.4, p. 44)

Apparently Wodehouse was the first to use this in the sense of a misunderstanding, as opposed to the technical sense of being connected to the wrong person in a telephone call.

pile on to a pot of tea (ch. 2.4, p. 44) *

The US magazine serial and book omit “to” here, which seems unidiomatic; the only results found by Google for “pile on a pot of tea” are later North American newspaper reprints of this story.

the scorched patch on his cheek where her eyes had rested (ch. 2.4, p. 45) *

A notable addition to a list of Wodehouse’s penetrating and injurious gazes!

one more grave among the hills (ch. 2.4, p. 48) *

See Ice in the Bedroom.

stevedores (ch. 2.5, p. 48)

Dock-workers employed in stowing or unloading cargo in a ship’s hold. From Spanish estivadores.

“What Fun Frenchmen Have” (ch. 2.5, p. 49) *

Announcements in magazines and newspapers during the middle 1920s suggested that Michael Arlen was preparing a play with this title, but it seems never to have opened on Broadway under that name. It was announced in 1931 as a screenplay for Ronald Colman, to be made by Samuel Goldwyn for United Artists, but does not appear in Colman’s IMDB filmography, nor in the IMDB author credits for Michael Arlen, so it may never have been gotten past the censors.

his work was considered swift (ch. 2.5, p. 49) *

That is, he led a fast life. Compare Wodehouse’s 1917 lyric for “Cleopatter” from Leave It to Jane, to a tune by Jerome Kern:

And ev’ry one observed with awe

That her work was swift, but never raw.

never going to bed before five (ch. 2.5, p. 50) *

The US first edition expands this to “five in the morning”; the magazine serial does not.

Greta Garbo ... Constance Bennett ... Norma Shearer (ch. 2.5, p. 50)

Greta Garbo (born Greta Gustafsson, 1905–1990), Constance Bennett (1904–1965), and Norma Shearer (1902–1985) were all famously beautiful film actresses of the period.

British Broadcasting Company (ch. 2.5, p. 51)

A small slip, understandable as Wodehouse had been so much outside England – the privately-owned British Broadcasting Company, which started radio broadcasts in 1922, had become the publicly-owed British Broadcasting Corporation in 1927. Fat-stock prices are still – or at least were until very recently – broadcast on BBC radio in the early mornings for the benefit of farmers.

engaged me as his valet (ch. 2.5, p. 53)

Ashe Marson in Something Fresh and Joss Weatherby in Quick Service also find themselves unexpectedly valeting for irascible Americans.

stopped a sandbag with the back of his head (ch. 2.5, p. 54) *

See Right Ho, Jeeves.

Devonshire House (ch. 2.5, p. 54)

Devonshire House is situated on the block formed by Piccadilly, Berkeley Street, Mayfair Place and Stratton Street, opposite the Ritz Hotel, and over the modern Green Park tube station. The original Devonshire House, the London residence of the Dukes of Devonshire, was demolished in 1924, to be replaced by the present building. Presumably Packy had an apartment there.

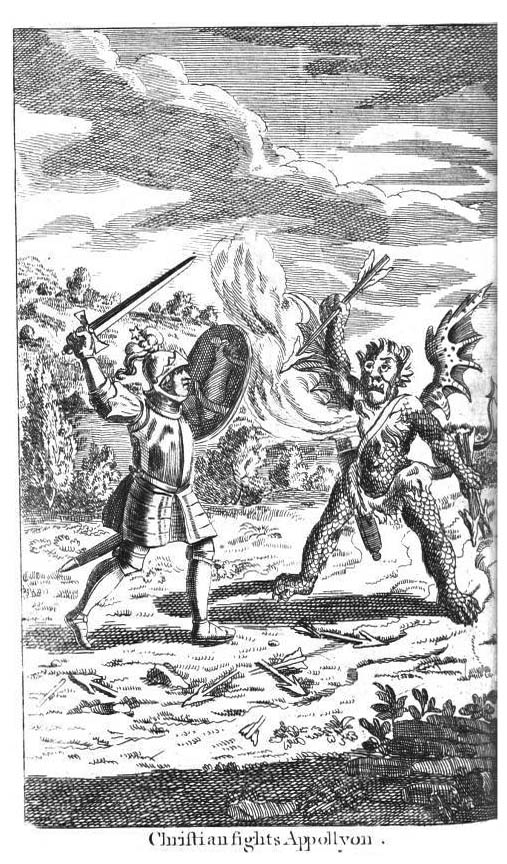

Slough of Despond (ch. 2.5, p. 54)

A deep bog that has to be crossed in Pilgrim’s Progress Pt 1, to get to the Wicket Gate.

Flying Cloud (ch. 2.6, p. 55)

The original Flying Cloud was a celebrated American clipper, launched in 1851.

fully found (ch. 2.6, p. 55) *

Completely equipped; said of a ship, in maritime usage dating to the eighteenth century.

bootlegger (ch. 2.6, p. 56)

Supplier of illicit drink. Apparently, the original bootleggers carried flasks of whisky concealed in the legs of their boots. The term dates back to the 1890s.

strict lemonade ... tie a can (ch. 2.6, p. 57)