The Clicking of Cuthbert

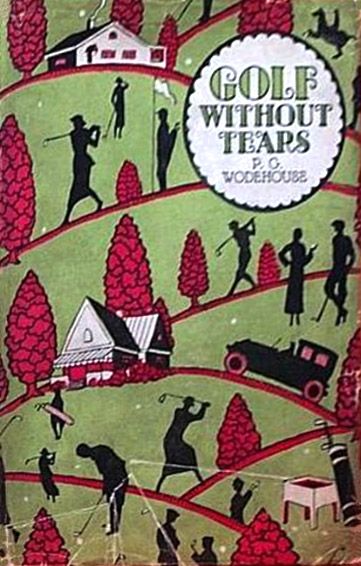

(US: Golf Without Tears)

by

P. G. Wodehouse

Literary and Cultural References

The following notes attempt to explain cultural, historical and literary allusions in Wodehouse’s text, to identify his sources, and to cross-reference similar references in the rest of the canon. The original version of these annotations was prepared by the late Terry Mordue. The notes have been somewhat reformatted and edited, but credit goes to Terry for his original efforts, even while we bear the blame for errors of fact or interpretation. The following paragraphs are Terry’s introduction:

The Clicking of Cuthbert was published by Herbert Jenkins, London, on 3 February 1922. The US edition, under the title Golf Without Tears, was published by George H. Doran, New York, on 28 May 1924.

The Clicking of Cuthbert was published by Herbert Jenkins, London, on 3 February 1922. The US edition, under the title Golf Without Tears, was published by George H. Doran, New York, on 28 May 1924.

There are a number of slight differences between the two editions, chiefly as regards the names of places, golfers and the like, which were adapted to suit the intended readership. These annotations refer to the UK edition, specifically (as regards page numbers) the Penguin edition, 1999 reprinting.

As the text of The Clicking of Cuthbert is freely available from Project Gutenberg and Blackmask, I have included a copy on this site, with hyperlinked cross-references to these annotations. I have also marked up this text to show all differences between the US and English editions.

Fore! (pp. ix–x)

The incident involving John Henrie and Pat Rogie was depicted in a painting, “The Sabbath Breakers” (aka “During the Time of the Sermonses”), by the English artist John Charles Dollman (1851–1934); the painting was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1896 and now hangs in the Harris Art Gallery in Preston, Lancs.

The incident involving John Henrie and Pat Rogie was depicted in a painting, “The Sabbath Breakers” (aka “During the Time of the Sermonses”), by the English artist John Charles Dollman (1851–1934); the painting was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1896 and now hangs in the Harris Art Gallery in Preston, Lancs.

Deepthi Sigireddi found another reference (though with Rogie misspelled as Royie) in “The Birth of Golf” by Douglas Story, in Munsey’s Magazine, June 1902, p. 322; this account also mentions Robert Robertson of Perth, as Wodehouse does in this preface.

the pretty on the dog-leg hole (p. ix)

“Pretty” is an old name for the fairway on a golf hole. A dog-leg hole is one where the fairway makes an abrupt change of direction.

farceur (p. ix)

French: a joker, buffoon; one who writes or acts in farces.

and laugh, like Figaro (p. ix)

Je me presse de rire de tout, de peur d’être obligé d’en pleurer.

(I hasten to laugh at everything for fear of being obliged to weep at it.)

(1732–99), Le Barbier de Séville, Act I, sc 2 (1775)

Beaumarchais’s play formed the basis for several operas in the early years of the 19th century. The best-known today is that by the Italian composer Gioachino Rossini (Il Barbiere di Siviglia, 1816), with libretto by Cesare Sterbini.

The Clicking of Cuthbert (pp. 1–18)

“The Clicking of Cuthbert” was first published in October 1921 in the Strand Magazine (UK) under the title “The Unexpected Clicking of Cuthbert.” Its first US appearance was in July 1922, in The Elks Magazine, under the title “Cuthbert Unexpectedly Clicks.”

as the poet says (p. 1)

The poet is Matthew Arnold, writing not about golf but about another poet, Sophocles:

. . . But be his

My special thanks, whose even-balanced soul,

From first youth tested up to extreme old age,

Business could not make dull, nor passion wild;

Who saw life steadily, and saw it whole;

The mellow glory of the Attic stage,

Singer of sweet Colonus, and its child

, “To a Friend" (1849)

‘Be of good cheer’ (p. 2)

But straightway Jesus spake unto them, saying, Be of good cheer; it is I; be not afraid.

Matthew 14:27

Situated at a convenient distance . . . company’s own water (p. 2)

Wodehouse is parodying the style of an English estate agent (US: realtor).

Gravel soil would presumably be thought desirable for its free-draining properties.

“Company’s own water” implies that the properties are supplied by a private water company. Before the enactment of the 1945 Water Act, the supply of domestic water in UK was largely unregulated, a survey in 1915 identifying 2160 undertakings and 786 local authorities that were involved in water supply.

summum bonum (p. 2)

The phrase summum bonum (Latin: the greatest good) was used by Cicero in his philosophical treatise De Finibus Bonorum et Malorum, in which he expounded for his Roman readers the beliefs of the ancient philosophers regarding the ultimate goal of human life.

many a golfer had foozled his drive (p. 3)

Foozle (colloquial): to bungle a golf stroke (possibly from German dialect fuseln, to work badly).

a sliced ball (p. 3)

A sliced ball is one which has been mis-hit, the strike imparting a spin to the ball that causes it to curve strongly to the right (for a right-handed golfer).

the rising young novelist (who rose at that moment a clear foot and a half) (p. 3)

One of Wodehouse’s most extreme vertical jumps; see Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit.

Many other promising professionals are so described, without the associated leaping:

There is a “Moments in the Nursery” page, conducted by Luella Granville Waterman, to which parents are invited to contribute the bright speeches of their offspring, and which bristles with little stories about the nursery canary, by Jane (aged six), and other works of rising young authors.

Psmith, Journalist, ch. 1 (1909/15)

The first man to think of it was Solly Quhayne, the rising young [vaudeville] agent.

The Swoop!, II.2 (1909)/“The Military Invasion of America” (1915)

All over the country promising young plasterers and rising young motor-men are throwing up steady jobs in order to devote themselves to the new profession.

“The Alarming Spread of Poetry” (1916)

Daughters of solid and useful men; sisters of rising young politicians like himself; nieces of Burke’s Peerage; he could have introduced without embarrassment one of these in the rôle of bride-elect.

The Little Warrior (1920/21)

In the demeanor of Roland Moresby Attwater, that rising young essayist and literary critic, there appeared, as he stood holding the door open to allow the ladies to leave his Uncle Joseph’s dining room, no outward and visible sign of the irritation that seethed beneath his mud-stained shirt front.

“Something Squishy” (1924; in Mr. Mulliner Speaking, 1929/30)

While Jane sat enthroned on her cushion, exchanging gay badinage with rising young poets and laughing that silvery laugh of hers, William would have to stand squashed in a corner, trying to hold off some bobbed-haired female who wanted his opinion of Augustus John.

“Jane Gets Off the Fairway” (1924; in The Heart of a Goof, 1926)

If you threw a brick from any of its windows, you would be certain to brain some rising young interior decorator, some Vorticist sculptor or a writer of revolutionary vers libre.

The Small Bachelor, ch. 1 (1926/27)

Hearing it, she experienced a quite definite twinge of regret that she was unable to reply that Adrian was a rising young barrister or even an earnest toiler in an office, and it made her feel disloyal.

Summer Moonshine, ch. 10 (1937)

Moustache-twiddling reminded him of Lionel Green, and he hated to be compelled to think about that rising young interior decorator.

Money in the Bank, ch. 15 (1942)

For there was now a new link between them—that rising young composer, Jerome D. Kern.

Bring On the Girls, ch. 2 (US edition, 1953)

I’m gradually assembling a plot where a rising young artist is sent for to Blandings to paint a portrait.

Letter to William Townend, dated August 24, 1932, in Performing Flea (1953); dated June 11, 1934 in Author! Author! (1962)

Here, obviously, was a rising young diplomat who knew all about protocol and initialling memoranda in triplicate and could put foreign spies in their places with a lifted eyebrow.

Frozen Assets/Biffen’s Millions, ch. 2.3 (1964)

When Lancelot Bingley, the rising young artist, became engaged to Gladys Wetherby, the poetess, who in addition to her skill with the pen had the face and figure of the better type of pin-up girl and eyes of about the color of the Mediterranean on a good day, he naturally felt that this was a good thing and one that should be pushed along.

“A Good Cigar Is a Smoke” (in Plum Pie, 1966/67)

There was about him something suggestive of a rising young barrister who in his leisure hours goes in a good deal for golf and squash racquets, and that, oddly enough, was what he was.

A Pelican at Blandings, ch. 2 (1969)

baggy knickerbockers (p. 3)

Knickerbockers are loose breeches, gathered at the knee, which were once popular with golfers. They have largely fallen out of fashion, though the American professional, the late Payne Stewart, was well-known for wearing them. The name is said to have been coined by Washington Irving, whose humorous History of New York (1809), ostensibly written by a Dutch-American scholar, ‘Diedrich Knickerbocker,’ was a satirical account of New York State during the period of Dutch occupation (1609–64) and featured Dutchmen in wide breeches.

insisted on playing his ball where it lay (p. 3)

Under Rule 27 of the modern Rules of Golf, Cuthbert’s ball would be ruled “out of bounds” and, far from playing it “where it lay,” he would be required to return to the spot from where he played the errant shot and play another shot, under penalty of one stroke.

The concept of “out of bounds” was not precisely defined until the Rules of Golf Committee of the Royal & Ancient Golf Club issued its first code of rules, in 1899. Were it not for the subsequent references to Lenin and Trotsky, we might possibly infer from this that the action of “The Clicking of Cuthbert” takes place in the closing years of the 19th century.

working away with a niblick (p. 3)

As the niblick was a club with a heavy iron head, most experts would advise against its use at the dining table.

a complete frost (p. 3) °

Slang: failure, disappointment. Originally theatrical jargon for a cold reception by an audience.

twenty minutes after he had met Adeline (p. 4)

Cuthbert is clearly an exceedingly fast golfer. When he meets Adeline, he has just played his second (or subsequent) shot at the fourth, yet a mere 20 minutes later he has not only managed a hole-in-one at the eleventh but, we must assume, has also completed the intervening six holes. A good golfer, playing alone and not held up by other players, might possibly hope to complete a round of 18 holes of golf in something under two hours. Cuthbert seems to be on course to reduce this time by about 50%.

the local Cottage Hospital (p. 4)

A cottage hospital was a small hospital, usually without resident doctors (and, as the name suggests, sometimes housed in nothing more substantial than a cottage), which served a rural area or a small urban settlement. Once a common feature in England, they have now all but disappeared.

the lion . . . lay down with the lamb (p. 4)

Although deriving from the prophecies of Isaiah, this oft-quoted phrase is a corruption of the Biblical sources, in which it is the wolf, not the lion, that is paired with the lamb:

The wolf also shall dwell with the lamb, and the leopard shall lie down with the kid; and the calf and the young lion and the fatling together; and a little child shall lead them.

Isaiah 11:6

The wolf and the lamb shall feed together, and the lion shall eat straw like the bullock: and dust shall be the serpent’s meat. They shall not hurt nor destroy in all my holy mountain, saith the Lord.

Isaiah 65:25

badly stymied (p. 4)

Slang: frustrated.

Appropriately, the slang meaning derives from a golfing term that referred to a situation which formerly arose in matchplay when, on the putting green, the opponent’s ball lay between the player’s ball and the hole, thus frustrating a direct putting stroke.

describe the Taj Mahal as a pretty nifty tomb (p. 5)

The Taj Mahal, at Agra, in India, is one of the wonders of the modern world. Constructed entirely of white marble, and located on the bank of the Jamuna river, it was erected on the orders of the Moghul Emperor Shah Jahan as a monument to his deceased wife and queen, Mumtaz Mahal, whose tomb it contains. Legend has it that Shah Jahan intended to build another edifice, in black marble, on the opposite bank of the river, to hold his own tomb, and to link the two with a bridge across the river, but modern scholars tend to dismiss this story as “romantic but wrong.” In any event, in 1658 AD, five years after the Taj Mahal was completed, Shah Jahan fell ill, precipitating a fratricidal revolt by his four sons which ended only when the third son, Aurangzeb, had succeeded in eliminating his brothers and imprisoning his father. Shah Jahan spent the rest of his life imprisoned in Agra fort, where he died in 1666 AD; he was buried alongside his wife.

It was as though some traveller, seeing the Taj Mahal by moonlight for the first time, had described it in a letter home as a fairly decent-looking sort of tomb.

Something Fishy/The Butler Did It, ch. 10 (1957)

Other references to the Taj Mahal, starting with those also mentioning moonlight:

She could scarcely show more enthusiasm if she were seeing the Taj Mahal for the first time by moonlight.

“An Englishman’s Home” (in Punch, May 4, 1955)

Not that he would have derived any greater spiritual refreshment from it if the boxes had been the Champs-Elysées in springtime and the ash-cans the Taj Mahal by moonlight.

Ice in the Bedroom, ch. 16 (1961)

He could not have gazed on him with more appreciation if he had been the Taj Mahal by moonlight.

Bingo on Mr. Purkiss in “Bingo Bans the Bomb” (1965; in Plum Pie, 1966)

It was a moment for stiffening the sinews and summoning up the blood, as recommended by Shakespeare, and he was in the process of doing this, when a key clicked in the door, the door opened and Ivor Llewellyn lumbered in, paused on the threshold, mopped his forehead and stood gazing at him with something of the enthusiasm of one seeing the Taj Mahal by moonlight.

Pearls, Girls and Monty Bodkin, ch. 3 (1972)

‘I thought you might like to come and see the Empress by moonlight,’ he said in the manner of someone inviting a friend to take a look at the Taj Mahal.

Sunset at Blandings, ch. 12 (1977)

And:

About the front of the premises of Messrs Thorpe & Briscoe, for instance, who sell coal in Dover Street, there is as a rule nothing whatever to attract fascinated attention. You might give the place a glance as you passed, but you would certainly not pause and stand staring at it as at the Sistine Chapel or the Taj Mahal.

Leave It to Psmith, ch. 3 (1923)

I get much more kick out of a place like Droitwich, which has no real merits, than out of something like the Taj Mahal.

Letter to William Townend, 29 June 1931 (dated May 19 in Performing Flea, 1953)

Opening his eyes, which he had closed in order not to be obliged to see Mr. Llewellyn—who, even when you were at the peak of your form, was no Taj Mahal—he gradually brought into focus a fine, upstanding girl in heather-mixture tweed and recognized in her his cousin, Gertrude Butterwick.

The Luck of the Bodkins, ch. 2 (1935)

Mr. Molloy, who was gazing at the ham like one who sees the Taj Mahal for the first time, did not immediately observe it.

Money in the Bank, ch. 12 (1942)

He stared at those trousers. Travellers in India had gazed at the Taj Mahal with a less fascinated intensity.

Frozen Assets/Biffen’s Millions, ch. 10 (1964)

excite pity and terror, as Aristotle recommends (p. 7)

In his Poetics, written some time in the 4th century BC, Aristotle put forward the idea that the function of dramatic tragedies is to evoke pity and fear (terror) in the audience and to effect a healthy purgation of these emotions, a process to which he gave the name katharsis.

a full iron for his mashie shots (p. 7)

A mashie was a mid-iron, the equivalent of the modern 5- or 6-iron. A full iron would be the equivalent of the modern 3-iron. A competent golfer will hit a 3-iron some 20–30 yards further than a 5- or 6-iron, so if Clarence needs to use a full iron where a mashie would previously have sufficed, he has lost about this distance with his mashie shots.

to duck and back away (p. 7)

A boxing metaphor; its sense in this case being, to evade the question.

Vladimir Brusiloff (p. 7)

The name Brusiloff may, perhaps, have been inspired by Alexei Alexeyevich Brusilov, a Russian general prominent during World War I and, later, in Russia’s war against Poland in 1920. Brusilov gave his name to the Russian offensive which he organised in 1916 against Austria, an offensive which, while initially successful, was eventually repulsed at a cost of over one million Russian lives.

throwing in the towel (p. 8)

Another boxing metaphor, meaning to give up the struggle; the term derives from the practice whereby, if a boxer was unable to rise from his stool at the start of a round, one of his seconds would throw a sponge or towel into the ring, signifying that his boxer was conceding the fight.

page three hundred and eighty, when the moujik (p. 8)

A moujik (or ‘muzhik’) is a Russian peasant. Wodehouse is not referring to any specific work, merely making fun of the weighty Russian novels written by such authors as Dostoyevsky, Gogol, and Turgenev.

Vardon on the Push-Shot (p. 8)

While Harry Vardon did not write a book on the push-shot, he did popularise this very difficult stroke, of which he was a master. The push-shot does not, in fact, involve ‘pushing’ the ball; rather, the ball is struck in such a way as to give it a low trajectory and considerable backspin, thus making it a very useful shot for an approach to the green with a strong following wind — the low trajectory ensures that the ball will not be caught by the wind and overshoot the green, while the backspin ensures that the ball will ‘bite’ when it pitches on the green.

the daily report in the papers (p. 8)

One of Wodehouse’s infrequent topical allusions (there is another in Summer Moonshine), this presumably refers to the civil war of 1918–20 between the ‘Reds’ (Bolsheviks, later Communists) and the ‘Whites’ (a loose coalition of Russian Army units led by anti-Bolshevik officers, Mensheviks and Social Revolutionaries). When the civil war started, Russia was still at war with Germany and the signing by the Bolsheviks of a peace treaty with Germany, effectively ending Russia’s involvement in World War I, was one of the factors which increased popular support for the Bolsheviks and enabled them to defeat the Whites.

his lecture at Queen’s Hall (p. 9)

Queen’s Hall, in Upper Regent Street, London, opened in 1893. Two years later, it hosted the inaugural Henry Wood Promenade Concert and it remained the home of the Proms for the next 45 years. On the night of 10 May 1941 it was destroyed during a Luftwaffe air raid. The site is now occupied by an hotel and a BBC office block.

this love-feast (p. 9)

See A Damsel in Distress.

a dense zareba of hair (p. 10)

In Sudan, a zareba (Arabic: zaribah, a pen or enclosure for cattle) is a stockade, often a thorn-hedge, providing protection against wild animals and enemies.

his quiet home in Nijni-Novgorod (p. 10)

The city of Nijni-Novgorod, situated at the confluence of the Volga and Oke rivers, about 400 miles east of Moscow, is the third largest in Russia. In 1932, the city was re-named Gorkii (or Gorky), in honour of the writer. It reverted to its pre-Soviet name in 1992.

Abe Mitchell and Harry Vardon (p. 15)

Abe Mitchell (1887–1947) was possibly the finest golfer never to win the Open Championship. In 1920, in the first Open Championship after the war, Mitchell built a lead of 13 strokes, only to see George Duncan make up the deficit in a single day and take the title. In June 1926, Mitchell and Duncan teamed up to represent the British Professional Golfers’ Association in a match against its US counterpart, represented by Walter Hagen and Jim Barnes; the British team won by the convincing margin of 13–1. Watching the match was a wealthy English businessman, Samuel Ryder, who had earlier employed Mitchell as his golf coach. Ryder had the idea for a biennial match between Britain and the US and donated a trophy, the Ryder Cup, which was first competed for in 1927 at Worcester, Massachusetts. Mitchell, who had been appointed captain of the British team, was stricken with appendicitis and was unable to take part in the match, which the US won. The Ryder trophy is a solid gold cup, on the lid of which is a figure of a golfer: the golfer depicted is Abe Mitchell.

Harry Vardon (1870–1937) was one of the greatest golfers of his era. In 1894, he came fifth in the Open Championship and, two years later, tied with J H Taylor (who had won the event in 1894 and 1895), winning in a play-off. He won again in 1898 and 1899 and was runner-up in each of the next three years. In 1903, he again won the Open Championship, playing despite a severe bout of tuberculosis which permanently affected his health. After winning nothing for the next eight years, he won the Open Championship again in 1911 and, in 1914, won his sixth Open title, setting a record that remains unsurpassed; the runner-up, J H Taylor, was also seeking his sixth win. In 1900, in his first visit to the US, Vardon won the US Open Championship; he was runner-up on two further occasions, in 1913 and 1920.

the effervescent Muscovite (p. 16)

In its narrower sense, ‘Muscovite’ describes somebody who originates from Moscow; in its wider sense, as used here, it applies to all Russians — Brusilov has already made it clear that Nijni-Novgorod, not Moscow, is his home.

Lenin and Trotsky (p. 16)

Vladimir Ilyich Lenin (1870–1924) was the first leader of the Soviet Union. Lenin came from a revolutionary background — in 1886, his brother was executed for plotting against the Tsar, Alexander III — and after qualifying as a lawyer, Lenin moved to St. Petersburg, where he started a revolutionary movement based on Marxist principles. In 1895, he served 15 months in jail, followed by internal exile to Siberia until 1900. On his release, he moved to Switzerland, where he rose steadily in the Social Democratic party. In March 1917, when protests by steelworkers in St. Petersburg led to the downfall of the Tsar, the Duma (parliament), led by Alexander Kerensky, usurped power. Kerensky was in no hurry to take Russia out of the war against Germany, so Lenin made a deal with the Germans, agreeing to bring the war to an end if they would assist him in getting into Russia safely. In October 1917, Lenin’s supporters overthrew Kerensky in an almost bloodless coup and Lenin was named as president of the Society of People’s Commissars (the Communist Party). One of his first actions was to make a peace treaty with Germany. In May 1922, Lenin suffered the first of a series of strokes, which led to his death in January 1924.

Leon Trotsky (1879–1940) was born Lev Davidovich Bronstein; he adopted the pseudonym Trotsky in 1902 after he had escaped from Siberian exile and fled to Europe. Although he worked alongside Lenin in Switzerland, he soon disagreed with Lenin’s Bolshevik faction, siding instead with the Mensheviks. He returned to Russia to take part in the 1905 revolution and was again jailed and exiled, and again he escaped. In March 1917 he was in New York but rushed back to Russia, where he directed the armed uprising that overthrew Kerensky’s provisional government in October 1917 and later negotiated the peace treaty of Brest-Litovsk between Russia and Germany. Lenin’s illness caught him unawares, allowing Stalin to seize power and attack Trotsky, who was expelled from the Politburo, exiled to Central Asia and, in 1929, expelled from the Soviet Union. Trotsky spent the rest of his life publishing savage attacks on Stalin’s regime and moving from country to country to avoid Stalin’s agents. In August 1940, one of these agents caught up with him in Mexico and murdered him.

A Woman is Only a Woman (pp. 19–40)

“A Woman is Only a Woman” was first published in June 1919 in the Saturday Evening Post (US) and in October 1919 in the Strand Magazine (UK).

The title is a reference to Rudyard Kipling’s “The Betrothed”:

Open the old cigar-box – let me consider anew —

Old friends, and who is Maggie that I should abandon you?

A million surplus Maggies are willing to bear the yoke;

And a woman is only a woman, but a good Cigar is a Smoke.

Light me another Cuba – I hold to my first-sworn vows.

If Maggie will have no rival, I’ll have no Maggie for Spouse!

Departmental Ditties and Other Verses (1886)

even a topped shot (p. 19)

A topped ball rarely travels more than a few tens of yards.

the love of Damon for Pythias, of David for Jonathan, of Swan for Edgar (p. 20)

The story of Damon and Pythias is recounted by several classical authors, e.g. Diodorus Siculus, Diogenes Laertius, Cicero, Hyginus, and Polyaenus. Although details vary, the essential story is the same: Damon and Pythias are friends, one of whom (the authors disagree on which!) is condemned to death by Dionysius of Syracuse. The condemned man is given leave to return home and put his affairs in order before his execution, on condition that his friend agrees to be put to death in his place if he does not return in time. Such is their friendship that not only do they both agree to this but the condemned man returns at the due time; Dionysius, impressed by this loyalty between the two friends, pardons the condemned youth and frees him.

See also Money in the Bank.

The story of the friendship between David and Jonathan is recounted in the Bible:

And it came to pass, when he had made an end of speaking unto Saul, that the soul of Jonathan was knit with the soul of David, and Jonathan loved him as his own soul.

And Saul took him that day, and would let him go no more home to his father’s house.

Then Jonathan and David made a covenant, because he loved him as his own soul.

And Jonathan stripped himself of the robe that was upon him, and gave it to David, and his garments, even to his sword, and to his bow, and to his girdle.

1 Samuel 18:1–4

See also Love Among the Chickens and A Damsel in Distress.

Swan and Edgar were two London drapers who set up business together in 1812. The business grew into one of the most fashionable department stores in London, with premises at the southern end of Regent Street, where it adjoins Piccadilly Circus. The store closed in January 1982, the premises now being occupied by a record store and the offices of an insurance company.

The firm of Crosse & Blackwell, now part of the giant Swiss food group, Nestlé, was a pioneer in the technology of canning food.

incompetence with the spoon (p. 21)

Nothing to do with table manners! A spoon was an old golf club.

a cut-down cleek (p. 21)

A cleek was another old club. A ‘cut-down’ club is one whose shaft has been shortened to allow it to be used by a smaller person.

some spavined elder (p. 21)

A spavined elder would have the greatest difficulty in playing golf, since the term refers to bone-spavin, an affliction of horses, in which a bony excrescence or hard swelling forms on the inside of the hock, the joint on the hindleg between the knee and the fetlock.

personal reminiscences of the Crimea War (p. 21)

The Crimean War began in late March 1854 — when Great Britain and France allied themselves with Turkey in the latter’s dispute with Russia — and ended exactly two years later, on 30 March 1856, with the signing of the Treaty of Paris. If it is assumed that the action of the story takes place in the late 1910s, anybody who took part in the Crimean War would by then be approaching the age of 80 years.

Gracechurch Street (p. 22)

Gracechurch Street lies at the heart of the City of London: Lloyds of London is only a hundred yards or so to the east, the London Stock Exchange and Bank of England a few hundred yards to the west, and The Monument, marking the spot where the Great Fire of London started in 1666, is just a short distance to the south.

Although the street is now largely given over to commerce, it was not always so: in Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, Elizabeth Bennet’s aunt and uncle, the Gardiners, have their home in Gracechurch Street and it is there that Lydia Bennet stays before her marriage to Wickham.

killing wasps with a teaspoon (p. 22)

With Spelvin she swayed over the waxed floor; with Spelvin she dived and swam; and it was Spelvin who, with zealous hand, brushed ants off her mayonnaise and squashed wasps with a chivalrous teaspoon.

“Rodney Fails to Qualify” (1924; in The Heart of a Goof, 1926)

Wasping is too sedentary for me. You wait till the creature is sitting waist-high in the jam and then shove him under with a teaspoon.

“A Day with the Swattesmore” (1929; in Louder and Funnier, 1932)

As Egbert rested for a moment from the task of trying to dredge the sand from a plateful of chicken salad, his eyes had fallen on a divine girl squashing a wasp with a teaspoon.

“Best Seller” (1930; in Mulliner Nights, 1933)

A Tankard of Stout had just squashed a wasp as it crawled on the arm of Miss Postlethwaite, our popular barmaid, and the conversation in the bar-parlour of the Angler’s Rest had turned to the subject of physical courage.

“Monkey Business” (1932; in Blandings Castle and Elsewhere, 1935)

“The first time I met Gertrude,” he began, “was at a picnic, and it was absolutely a case of love at first sight. I squashed a wasp for her with a teaspoon, and from that moment never looked back.”

The Luck of the Bodkins, ch. 3 (US version, 1935) [UK text omits with a teaspoon]

“I wouldn’t trust Crispin to squash a wasp with a teaspoon.”

Willoughby Scrope in The Girl in Blue, ch. 13.5 (1970)

Sandy MacBean’s How to Become a Scratch Man (p. 24)

While this seems to be one of Wodehouse’s fictitious titles, his subsequent description is only a slightly exaggerated caricature of a style of golf tuition that is still to be found in golf magazines.

during the war (p. 26)

The subsequent reference to ‘German propaganda’ makes it clear that the war referred to is World War I.

strict Royal and Ancient rules (p. 29)

In the early days of golf, there were no agreed rules. Individual clubs began developing their own rules from about the middle of the 18th century. By the early 19th century, two clubs — the Honourable Company of Edinburgh Golfers and the Society of St. Andrews Golfers — were the leading rule-makers. At first, the Edinburgh club led the way, but by 1839 it was basing its rules on those of the St. Andrews club, by now renamed as the Royal and Ancient Golf Club of St. Andrews. The R & A’s influence grew throughout the 19th century but it did not become the accepted rule-making authority until 1897, when it formed a Rules of Golf Committee; the code of rules proposed by this committee, and adopted in 1899 by the R & A, was the first code to gain world-wide recognition.

The United States Golf Association had, from its inception in 1895, adopted the R & A Rules, but disagreements arose throughout the first half of the 20th century and the rules under which golf was played in the US and the rest of the world began to diverge significantly. In 1952, the two bodies finally resolved their differences, issuing a unified code of rules. Although the Rules have been changed several times since, usually at four-year intervals, the changes have generally been agreed — and the revised Rules issued jointly — by the R & A and USGA.

no grounding niblicks in bunkers (p. 29)

What is now Rule 13.4 of the Rules of Golf prohibits a player from touching the ground in a bunker with a club (or anything else) except when making a stroke, the intention being to prevent the player from testing the condition of the hazard (e.g. checking whether the sand is soft or compacted) or from improving the condition of his ball before he plays his shot. The penalty for a breach of the rule is two strokes in strokeplay, loss of the hole in matchplay.

shall be considered holed-out (p. 29)

Under the Rules of Golf, a ball is defined as ‘holed’ when it is at rest within the circumference of the hole and all of it is below the level of the lip of the hole.

missing the ball counts as a stroke (p. 29)

A stroke is defined in the Rules as “the forward movement of the club made with the intention of fairly striking at and moving the ball”; whether the club actually strikes the ball is irrelevant. The polite name for a stroke which misses the ball is an “air shot.”

may not pull up all the bushes (p. 29)

In fact, the Rules provide that a player “shall not improve . . . the area of his intended stance or swing . . . by . . . moving, bending or breaking anything growing or fixed” (Rule 13–2). Thus, a player can remove leaves or loose twigs, for example, always provided that his ball does not move in the process, but he certainly cannot pull up bushes, or even break off an interfering branch.

all Nature smiled (p. 30)

See A Damsel in Distress.

Braid’s Advanced Golf (p. 30)

James Braid (1870–1950) was, with J H Taylor and Harry Vardon, one of the “Triumvirate” of golfers who dominated the game at the start of the 20th century. Between 1894 (when Taylor won the first of his five Open Championship titles) and 1914 (when Vardon won the last of his six, in the last tournament before World War I caused it to be suspended for five years), the Triumvirate took the title in 16 of the 21 Open Championships; Braid won his five titles between 1901 and 1910, becoming the first player to win that many.

James Braid was one of the founders of the Professional Golfers’ Association and its first president. He later became a renowned golf course architect, the prestigious King’s and Queen’s courses at Gleneagles in Scotland being two of his lasting legacies. Braid was also a writer on golf and his Advanced Golf: Hints and Instruction for Progressive Players went through several editions after its first appearance in 1906.

Keats’s poem about stout Cortez (p. 30)

Oft of one wide expanse had I been told

That deep-brow’d Homer ruled as his demesne:

Yet did I never breathe its pure serene

Till I heard Chapman speak out loud and bold:

Then felt I like some watcher of the skies

When a new planet swims into his ken;

Or like stout Cortez when with eagle eyes

He star’d at the Pacific—and all his men

Look’d at each other with a wild surmise—

Silent, upon a peak in Darien.

, “On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer” (1817)

Darién is the eastern part of Panama, near the border with Colombia. As Wodehouse notes in his Introduction, Keats got his history wrong. Hernando Cortés (1485–1547) was the conquistador of Mexico who, between 1519 and 1521, overthrew the Aztec emperor Montezuma, having first defeated a Spanish army which his superior, Diego Velasquez, governor of Cuba, had sent to arrest him. But Cortés never travelled further west than the area around what is now Mexico City. It was Vasco Nuñez de Balboa (1475–1519) who, in September 1513, became the first European to see and set foot upon the eastern shore of what Ferdinand Magellan later named the Pacific Ocean. He is said to have waded into the ocean in full armour and claimed it and “all the shores it washed” for God and the King of Spain — and little good it did him: in 1518, Balboa, by now serving as Governor of Panama, was falsely accused of treason by his superior, Pedro Arias Dávila, governor of Darién, and in January 1519 he and four of his followers were executed.

This is one of Wodehouse’s favourite quotes, occurring, in one form or another, in many of the books, from at least Psmith in the City (1910) to Cocktail Time (1958). See, for example, Something Fresh, Sam the Sudden, Money in the Bank, The Code of the Woosters, and Stiff Upper Lip, Jeeves.

[Many more citations from 1907 to 1974 are listed at Thank You, Jeeves.]

The discs had been set back . . . fifth shot from the tee (p. 31)

“Discs” refers to the tee markers, which are often moved from day to day, in order to spread the wear and tear over the tee. James having topped the ball with his fourth shot, it remains on the tee when he comes to play his fifth shot.

a low, raking brassey shot (p. 31)

The brassie was a wooden-headed club with a brass sole-plate, hence its name.

The dashing player stands for a slice (p. 32)

Although the slice is normally regarded as an uncontrolled shot, a good player may, on occasions, play for a deliberate slice (or ‘fade’) when, as in this case, by doing so he can send his ball around the corner of a dog-leg. The danger is, as Peter discovers, that if the shot is not executed properly, the ball will finish up in the trees to the right of the fairway before it reaches the dog-leg.

their address should be good (p. 37)

The ‘waggle’ to which James refers is not part of the address and, indeed, the player has not ‘addressed the ball’ until he stops waggling the club!

lay it dead with my mashie-niblick (p. 39)

The mashie-niblick was a lofted club, equivalent to the modern 7-iron.

athletic enough to play Animal Grab (p. 39)

Animal Grab was a Victorian children’s card game, similar in concept to the game of Snap. It was played with a deck of cards depicting different animals.

a hefty drive is a slosh (p. 40)

This not only parodies Kipling’s line, it also reflects Wodehouse’s own sentiments as a golfer: the author E. Phillips Oppenheim said of Wodehouse’s approach to golf that “he had only one idea in his mind . . . and that was length . . . he went for the ball with one of the most comprehensive and vigorous swings I have ever seen.”

A Mixed Threesome (pp. 41–60)

“A Mixed Threesome” was first published in June 1920 in McClure’s Magazine (US) and in the Strand Magazine (UK) in March 1921.

“The Game of Golf is played by sides, each playing its own ball. A side consists either of one or of two players. If one player plays against another, the match is called ‘a single.’ If two play against two, it is called ‘a foursome.’ A single player may play against two, when the match is called ‘a threesome,’ or three players may play against each other, each playing his own ball, when the match is called ‘a three-ball match.’

The Rules of Golf, 1899 ed.

the Greens Committees (p. 41)

The Greens Committee is usually concerned with matters affecting the condition and maintenance of the course, not with membership and fees.

in a Lord Fauntleroy suit (p. 41)

Little Lord Fauntleroy (1886), by Frances Hodgson Burnett, featured a young boy, Cedric, whose first appearance in the story is described thus:

What the Earl saw was a graceful, childish figure in a black velvet suit, with a lace collar, and with love-locks waving about the handsome, manly little face, whose eyes met his with a look of innocent good-fellowship.

The style thus described (based on Burnett’s designs for her own sons) proved to be enormously popular with doting Victorian mothers, though probably not with sons condemned to wear such costume.

bongo . . . pongos . . . dongo (p. 44)

Of the many -ongo words in this story, only bongo is genuine, being the Swahili name given to the largest of the African forest antelopes, Boocercus euryceros. Some of the others have some affinity to the meaning given by Denton: pongo is an anthropoid ape, probably originally the gorilla, and is also old service slang for a soldier and an Australian colloquial term for an Englishman; while a donga (not dongo) is not undergrowth but a southern African term for a steep-sided gully of the sort carved by severe flash floods.

the silent watches of the night (p. 44) °

This seems to have its origin in Psalms 63:6 —

When I remember thee upon my bed,

and meditate on thee in the night watches.

The exact phrase is found in 19th century sermons, hymns, and other works, e.g.:

“Spirit of the past! look not so mournfully at me with thy great, tearful eyes!

Touch me not with thy cold hand!

Breathe not upon me with the icy breath of the grave!

Chant no more that dirge of sorrow, through the long and silent watches of the night!”

, “Hyperion”(1882)

In the silent watches of the night,

Came a still, small voice that said,

“Thorns and cross I bore for thee,

All thy sins on me were laid.”

, hymn text for “The Still, Small Voice”, 1877.

But half an hour of cool waiting so altered their opinion that they not only went to bed, but fell asleep; and were, moreover, not ecstatically charmed to be awakened some time afterwards by certain dulcet strains breaking in upon the silent watches of the night.

, Martin Chuzzlewit, ch 11 (1844)

See also Something Fresh, Bill the Conqueror, and Summer Moonshine.

costermongers (p. 44)

A costermonger (from ‘costard,’ a large apple) was a seller of apples and other fruit, later applied to somebody selling fruit and other wares, usually from a street-barrow. Although still to be found at fixed markets, they no longer roam the streets, shouting their wares in a loud voice, and the term itself is now rarely used, having been largely superseded by ‘greengrocer.’

See also Love Among the Chickens, Money in the Bank and The Code of the Woosters.

donah (p. 45)

Colloquially, a sweetheart (probably a corruption of Spanish doña or Italian donna)

See also Money in the Bank.

crossed the dividing line — the Rubicon, as it were (p. 52)

The Rubicon is a small river that, in Roman times, separated the province of Gaul (ruled by a governor, appointed by the Senate) from the territory under the direct authority of the Consuls in Rome. Following Pompey’s appointment as sole Consul in 52 BC, Julius Caesar, at that time Governor of Gaul, was ordered by the Senate to relinquish his command. Instead, in 49 BC, Caesar took his troops across the Rubicon, offering a direct challenge to the authority of Pompey and the Senate, and instigating a civil war.

To ‘cross the Rubicon’ is thus to make an irrevocable decision, to take a step from which there is no turning back.

Silver King (p. 57)

Silver King golf balls were manufactured by The Silvertown Co, Ltd, of Woolwich, London. Silvertown thrived in the early decades of the 20th century, producing golf balls with a mesh or lattice cover (until the 1920s, the now-ubiquitous dimple pattern was protected by a patent that was held by the Spalding Company).

Sundered Hearts (pp. 61–81)

“Sundered Hearts” was published simultaneously in the UK (Strand Magazine) and US (McClure’s Magazine) in December 1920.

You have the honour (p. 62)

“The player who is to play first from the teeing ground is said to have the ‘honour’.” (Rules of Golf, Definitions)

Old Tom Morris . . . young Tommy Morris (p. 63)

“Old” Tom Morris (1821–1908) was born at St. Andrews but moved to become greenkeeper at Prestwick in 1851, the same year in which his son (“Young” Tom) was born. He returned to St. Andrews in 1865, first as greenkeeper, later as professional, and remained associated with the club until his death, which in fact resulted from injuries he sustained when he fell down the stairs in the clubhouse. While at Prestwick, Morris helped to establish the Open Championship, which was held there each year from 1860 until 1870 and in the first of which Morris was runner-up to Willie Park. He competed in every Open until 1896 and won the event four times.

“Young” Tom Morris (1851–75) is one of golf’s great champions. In 1868 he won the first of four consecutive Open Championships, becoming, at the age of 17, the youngest winner of the event (a record which still stands). After he won the 1870 Open, and, in the process, earned the championship belt outright, the organisers suspended the tournament while they considered ways of undermining such dominance. Their answer was to rotate the championship between three (nowadays seven) courses, the two new venues being Musselburgh and St. Andrews. But when, after a one-year hiatus, the tournament resumed in 1872, with the famous Claret Jug as the prize on a yearly basis, the winner was, yet again, “Young” Tom! In 1875, Morris had just finished a round at North Berwick when he received a telegram with news that his wife of one year was ill in childbirth; before he could reach home, another telegram brought news of her death. Morris never recovered from the shock and died a few months later, on Christmas Day 1875.

Dolly Vardon (p. 63)

“Dolly Vardon” or “Varden” is the name given to a colourfully-spotted species of trout, Salvelinus malma, found around north Pacific coasts; but the girl, “admirable in other respects,” was more probably thinking of Dolly Varden, a character in Charles Dickens’s Barnaby Rudge (and after whom, on account of her colourful costume, the fish is named).

a statuette of the Infant Samuel in Prayer (p. 63)

. . . there is a work by Sir Joshua Reynolds, said to be the only one in France, — an infant Samuel in prayer, apparently a repetition of the picture in England which inspired the little plaster image, disseminated in Protestant lands, that we used to admire in our childhood.

, A Little Tour in France, ch 25 (1884)

. . . the evenings at least were his own, and these he would prolong far into the night, now dashing off ‘A landscape with waterfall’ in oil . . . now stooping his chisel to a . . . life-size ‘Infant Samuel’ for a religious nursery.

, The Wrong Box, ch 7 (1889)

Sir Joshua Reynolds’s oil painting, “The Infant Samuel” (c. 1776), is in the Tate Gallery in London.

Wodehouse was fond of poking fun at statuettes of the Infant Samuel:

. . . a loaf of bread whizzed past his ear. It missed him by an inch, and crashed against a plaster statuette of the Infant Samuel on the top of the piano.

It was a standard loaf, containing eighty per cent of semolina, and it practically wiped the Infant Samuel out of existence.

“Pots o’ Money” (1911; in The Man Upstairs, 1914)

Jimmy found her staring in a rapt way at a statuette of the Infant Samuel which stood near a bowl of wax fruit on the mantelpiece.

Piccadilly Jim, ch 11 (1917)

See also A Damsel in Distress, Ukridge, The Code of the Woosters, and Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit.

a nasty cuppy lie (p. 66)

The ball is resting in a cup-like depression, possibly an old divot mark, which makes it difficult to play a proper shot.

In hot December weather when the grass is caddie high

I’ve driven clean an’ lost the ball an’ game,

When winter veld is burned an’ bare I’ve cursed the cuppy lie—

The language is the one thing still the same;

(1864–1941), “The Alien”

John Henry Taylor (p. 66)

J H Taylor (1871–1963) was a member of the “Great Triumvirate” with James Braid and Harry Vardon. He won four Open championships, the first in 1894, as well as the French and German Opens, but his main efforts, at a time when golf professionals were regarded almost as an inferior race, were devoted to speaking out on behalf of the pros and in helping to found the Professional Golfers’ Association. In 1949, the R&A recognised his achievements and contribution to golf by making him an honorary member.

first hole at Muirfield (p. 67)

Muirfield Links, at Gullane in East Lothian, is the home of the Honourable Company of Edinburgh Golfers, the world’s oldest golf club, founded in 1744. The original course was designed by Old Tom Morris, though it has since undergone major changes. The 448-yard first hole (par 4) was described by Jack Nicklaus as possibly “as tough an opening hole as there is anywhere in championship golf.”

St. George’s, Hanover Square (p. 69)

Although always referred to as St. George’s, Hanover Square, the church is actually on Mill Street, a short distance south of the Square. It has long been a fashionable venue for society weddings and those wed there have included Benjamin Disraeli, Theodore Roosevelt, Herbert Asquith, the novelist George Eliot (Mary Ann Evans), Percy Bysshe Shelley, and Lady Emma Hamilton.

‘The Voice That Breathed O’er St. Andrews’ (p. 69)

This is probably an alternative version of the well-known hymn, “The Voice That Breathed O’er Eden,” by John Keble (1792–1866):

The voice that breathed o’er Eden,

That earliest wedding-day,

The primal marriage blessing,—

It hath not passed away.

the birthplace of James Braid (p. 69)

James Braid was born at Earlsferry, Fife.

the Temple of Vespasian (p. 70)

The Temple of Vespasian and Titus was probably begun by Vespasian’s eldest son, Titus, after his father’s death in 79 AD and finished by Titus’s younger brother Domitian after Titus’s own death two years later.

Mortimer’s assessment of the Temple is not unjust, as all that remain today are a heap of stones and a few broken columns.

the Colosseum (p. 70)

The Colosseum, or Flavian Amphitheatre, was begun in 70 AD by Vespasian, inaugurated by Titus in 80 AD and completed by Domitian two years later.

The amphitheatre is in the shape of a vast ellipse, 188 m long and 156 m wide, and the facade is nearly 50 m high, which suggests that, even with a full brassie, Abe Mitchell would have struggled to carry it (that’s to say, clear it with a single shot).

Fiesole (p. 70)

Fiesole is an ancient hilltop town overlooking Florence and the Arno valley.

‘The Fall of the House of Usher’ (p. 70)

‘The Fall of the House of Usher,’ a short story published in 1839, is one of Poe’s most famous works. The story tells of a visit by the narrator to the home of his boyhood friend, Roderick Usher, who lives, with his sister Madeline, in an isolated house, deep in the forest. Madeline, his only relative, is dying of an undiagnosed and seemingly incurable malady. The “House of Usher” refers both to the house and to the Usher family, of which only one sibling in any generation has ever survived to start a family. In other hands, this could have made for an amusing tale, but Poe’s treatment, as so often in his work, lacks the spark of humour.

Auchtermuchtie in Scotland (p. 80)

Improbable as it may seem, there is an Auchtermuchtie in Scotland, though it uses the alias Auchtermuchty. One of the oldest towns in Fife, it boasts a charter that dates back to 1517, though it would probably prefer to have a golf course.

that thing of Tennyson’s (p. 81)

Wodehouse has taken a few liberties with the text, which, in the original, runs as follows:

. . . My bride,

My wife, my life. O we will walk this world,

Yoked in all exercise of noble end,

And so thro’ those dark gates across the wild

That no man knows. Indeed I love thee: come.

Yield thyself up: my hopes and thine are one:

Accomplish thou my manhood and thyself;

Lay thy sweet hands in mine and trust to me.

, “The Princess,” Canto VII (1847)

W. S. Gilbert wrote a play, “The Princess,” based on Tennyson’s poem and this later became the basis for the Gilbert and Sullivan operetta Princess Ida.

The Salvation of George Mackintosh (pp. 82–100)

“The Salvation of George Mackintosh” was first published in June 1921 in the Strand Magazine (UK). Its first US appearance was in September 1921, in McClure’s Magazine.

ancient Greek . . . hemlock (p. 82)

The ancient Greek philosopher Socrates, having been condemned to death in 399 BC on trumped-up charges of corrupting the youth of Athens and interfering with the religion of the city, died by drinking hemlock. His pupil, Plato, gave an account of Socrates’ trial and last days in his dialogues Euthyphro, Apology, Crito, and Phaedro.

like a toad under the harrow! (p. 82)

The toad beneath the harrow knows

Exactly where each tooth-point goes.

The butterfly upon the road

Preaches contentment to that toad.

, “Pagett, M.P.”, in Departmental Ditties and Other Verses (1886)

This is another quotation that Wodehouse uses frequently:

If ever there was a toad under the harrow, he was that toad.

“The Episode of the Exiled Monarch” in A Man of Means (1916)

“My poor old chap, my only feeling towards you is one of the purest and profoundest pity.” He reached out and pressed Sam’s hand. “I regard you as a toad beneath the harrow!”

Three Men and a Maid, ch 5 (1921/22)

Suffice it to say that by a few minutes to five o’clock he had become a mere toad beneath the harrow.

“Monkey Business” (1933; in Blandings Castle and Elsewhere, 1935)

“I’m just a toad beneath the harrow.”

Lord Shortlands in Spring Fever, ch. 5 (1948)

It is not pleasant for a nervous man who comes into a room expecting a Bourbon highball to find there a sister-in-law who even under the most favourable conditions has always made him feel like a toad beneath the harrow.

The Old Reliable, ch. 15 (1951)

‘It may be fun for her,’ I said with one of my bitter laughs, ‘but it isn’t so diverting for the unfortunate toads beneath the harrow whom she plunges so ruthlessly in the soup.’

Jeeves in the Offing, ch 10 (1960)

When Jeeves came shimmering in next morning with the breakfast tray, I lost no time in supplying him with full information re the harrow I found myself the toad under.

Stiff Upper Lip, Jeeves, ch. 10 (1963)

Where before he had been a mere toad beneath the harrow, under the influence of the generous fluid he had been converted into an up-and-coming toad which seethed with rebellion . . .

Pearls, Girls and Monty Bodkin, ch 7 (1972)

See also The Girl in Blue.

crackling of thorns (p. 82)

For as the crackling of thorns under a pot,

so is the laughter of the fool: this also is vanity.

Ecclesiastes 7:6

See also Summer Moonshine.

corruptio optimi pessima (p. 83)

Latin: the corruption of the best is the worst [offence].

Braid on the Push Shot (p. 85)

Cuthbert Banks’s deepest reading was said to have been Vardon on the Push Shot. In fact, neither Harry Vardon nor James Braid wrote a book devoted to the push shot.

like Alexander . . . no more worlds (p. 88)

It is often said that at the height of his conquests Alexander the Great (356–323 BC) wept “because he had no more worlds to conquer,” but this is surely nonsense. When he turned back at the Ganges, Alexander would have been well aware that there were unconquered territories beyond.

The Greek priest and historian Plutarch (c. 45–125 AD) gives a more plausible explanation. In his essay “On Contentment of the Mind,” he relates an anecdote in which Alexander wept after hearing the philosopher Anaxarchus talk about an infinity of worlds in the universe, explaining that “There are so many worlds, and I have not yet conquered even one.”

I played on them as on a stringed instrument *

Though this phrase has a classical sound, a Google search has not so far uncovered an appearance prior to Wodehouse of the term used in the sense of one person influencing others. The only similar passage with “stringed” so far found is one in an 1873 devotional work describing nature’s influence on susceptible personalities.

Whether or not Wodehouse coined it, he certainly popularized it, first using it in Psmith in the City (serialized as The New Fold, 1910) and continued to use it in Summer Lightning (1929), The Code of the Woosters (1938), Uncle Fred in the Springtime (1939), Full Moon (1947), Spring Fever (1948), The Old Reliable (1951), and Galahad at Blandings (1965).

But see The Mating Season for a similar quotation from The Scarlet Pimpernel (1903) without the word “stringed”—a book from which Wodehouse quoted other phrases.

Ray on Taking Turf (p. 90)

Although he never wrote a book on Taking Turf, Ray is probably Edward “Ted” R G Ray (1877–1943) who, like his friend Harry Vardon, was born in the Channel Islands. Ray won the Open Championship in 1912 and the following year was tied, with Vardon, in the US Open, both losing in a play-off to Francis Ouimet. Ray won the US Open in 1920 and tied for second in the Open in 1925. In 1927, he captained the Great Britain team in the first Ryder Cup match against the United States.

According to one who knew him in his later years, “Many a time in the evenings, when golf was finished for the day, you would find him surrounded by half a dozen of his friends amongst the club members. Leaning forward in his chair he would be laying down the law, driving home his arguments with an admonitory forefinger . . .” — almost a case of life imitating art!

it is not easy to lisp the word ‘Fore!’ (p. 90)

In fact, it’s impossible!

golf-balls . . . are rubber-cored (p. 94)

The rubber-cored golf-ball was introduced by Coburn Haskell in 1898. Although it looked just like the solid gutta percha ball, it was made by wrapping a solid rubber core in rubber thread, the whole being encased in a gutta percha sphere. Because it allowed an average golfer to gain an extra 20 yards’ distance off the tee, the Haskell ball soon made the guttie obsolete.

recent excavations in Egypt (p. 96)

This may be a topical allusion to the excavations begun by Howard Carter in the Valley of the Kings in 1915 in a search for the tomb of Tutankamun. With funding from Lord Carnarvon, an avid collector of Egyptian antiquities, Carter undertook excavations over several seasons, before eventually locating the entrance to Tutankamun’s tomb in early November 1922.

Jael the wife of Heber (p. 96)

Howbeit Sisera fled away on his feet to the tent of Jael the wife of Heber the Kenite: for there was peace between Jabin the king of Hazor and the house of Heber the Kenite.

And Jael went out to meet Sisera, and said unto him, Turn in, my lord, turn in to me; fear not. And when he had turned in unto her into the tent, she covered him with a mantle.

. . . .

Then Jael Heber’s wife took a nail of the tent, and took an hammer in her hand, and went softly unto him, and smote the nail into his temples, and fastened it into the ground: for he was fast asleep and weary. So he died.

And, behold, as Barak pursued Sisera, Jael came out to meet him, and said unto him, Come, and I will shew thee the man whom thou seekest. And when he came into her tent, behold, Sisera lay dead, and the nail was in his temples.

Judges 4:17–18, 21–22

Wodehouse was particularly fond of this story, which gets a mention in many of the books, including Ring for Jeeves, ch. 18 (and the earlier play, Come On, Jeeves, Act III); Much Obliged, Jeeves, ch. 8; The Code of the Woosters; Cocktail Time, ch. 2; and Uncle Dynamite, ch. 11.

Ordeal by Golf (pp. 101–123)

“Ordeal by Golf” was first published in December 1919 in Collier’s Weekly (US). Its first UK appearance was in February 1920 in the Strand Magazine, under the title “A Kink in His Character.”

The title is presumably a play on the mediaeval practices of “ordeal by combat” and “ordeal by water.”

peace beyond understanding (p. 101)

And the peace of God, which surpasseth all understanding, keep your hearts and minds in Christ Jesus.

Epistle of St. Paul to the Philippians 4:7

since the rubber-cored ball superseded (p. 101)

Roughly, within a couple of years of the start of the 20th century (see p. 94 above).

Marcus Aurelius (p. 102)

Marcus Aelius Aurelius Antoninus (121–180 AD) was adopted by the emperor Antoninus Pius. On the death of Antoninus in 161 AD, Marcus and his adoptive brother Lucius Verus succeeded as joint emperors, until 169 AD, when on Lucius’s death, Marcus became sole emperor. His fame rests chiefly on his Meditations (167 AD), a series of reflections, strongly influenced by Epictetus, and expounding a Stoic outlook on life.

Wodehouse’s quotations from Marcus Aurelius come directly from Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations, 10th ed., 1919, and differ significantly from those that can be found in other dictionaries of quotations, which are commonly based on the translation by George Long (as are the extracts here).

whatever may befall thee (p. 102)

Whatever may happen to thee, it was prepared for thee from all eternity; and the implication of causes was from eternity spinning the thread of thy being, and of that which is incident to it.

Meditations, x, 5

Nothing happens to any man which he is not formed by nature to bear. The same things happen to another, and either because he does not see that they have happened or because he would show a great spirit he is firm and remains unharmed. It is a shame then that ignorance and conceit should be stronger than wisdom.

Meditations, v, 18

that which makes the man no worse (p. 102)

That which does not make a man worse than he was, also does not make his life worse, nor does it harm him either from without or from within.

Meditations, iv, 8

recite bits of Gunga Din (p. 103)

“Gunga Din,” by Rudyard Kipling, was published in 1892 as one of the poems in the first series of “Barrack-Room Ballads.”

the cloven hoof (p. 105)

During the Middle Ages, Satan was often depicted as a goat, with cloven feet (an image carried over from the Greek god, Pan). Hence to “show the cloven foot (or hoof)” is to exhibit wicked intentions.

See also The Code of the Woosters.

Willie Park (p. 105)

Willie Park (174) of Musselburgh beat Tom Morris (176) of Prestwick over three rounds of the 12-hole Prestwick course in the first Open Championship, in 1860. Park went on to win the event a further three times.

the men who never replace a divot (p. 105)

The removal of a divot leaves a shallow scar — a divot-mark — in the fairway. If a player’s ball comes to rest in an unrepaired divot-mark, the player must play the ball as it lies, which may be more difficult than if the ball was off the fairway and unfairly penalises the player. Recognising this, Section I – Etiquette of the Rules of Golf states that “a player should ensure that any divot hole made by him . . . is carefully repaired.”

Wormwood Scrubbs (p. 106)

Wormwood Scrubs (not Scrubbs) prison, opened in 1874, is located in west London, roughly between North Kensington and East Acton. Prisoners confined there are usually serving fairly short sentences for less serious offences.

Thou seest how few be the things (p. 109)

And thou wilt give thyself relief, if thou doest every act of thy life as if it were the last, laying aside all carelessness and passionate aversion from the commands of reason, and all hypocrisy, and self-love, and discontent with the portion which has been given to thee. Thou seest how few the things are, the which if a man lays hold of, he is able to live a life which flows in quiet, and is like the existence of the gods; for the gods on their part will require nothing more from him who observes these things.

Meditations, ii, 5

won by six and five (p. 109)

In matchplay, a score of “six and five” indicates that after thirteen holes (i.e. with only five holes left to play) one player holds an unassailable lead of six holes. Such a score reflects a very one-sided contest.

the real tabasco (p. 110)

In 1870, a Louisiana plantation-owner, Edmund McIlhenny, obtained a patent for “Tabasco sauce,” a hot-pepper sauce made by straining mashed chili peppers and mixing the resulting juice with salt and vinegar. Around 1889, Heinz brought out “Heinz’s Tabasco Pepper Sauce” and other manufacturers followed suit. In the faced of increasing competition, McIlhenny succeeded, in 1906, in registering its Tabasco brand (the “real” Tabasco) as a trademark.

absolutely as mother makes it (p. 110)

the two-V grip (p. 111)

The “two-V” is an old-fashioned way of gripping a golf club. It was largely superseded by the overlapping grip, popularised (if not actually devised) by Harry Vardon.

Think on this doctrine (p. 112)

Recall to thy mind this conclusion, that rational animals exist for one another, and that to endure is a part of justice, and that men do wrong involuntarily . . .

Meditations, iv, 3

Let no act be done at haphazard (p. 112)

Let no act be done without a purpose, nor otherwise than according to the perfect principles of art.

Meditations, iv, 2

Search men’s governing principles (p. 114)

Examine men’s ruling principles, even those of the wise, what kind of things they avoid, and what kind they pursue.

Meditations, iv, 38

Nothing has such power to broaden the mind (p. 114)

For nothing is so productive of elevation of mind as to be able to examine methodically and truly every object which is presented to thee in life, and always to look at things so as to see at the same time what kind of universe this is, and what kind of use everything performs in it, and what value everything has with reference to the whole . . .

Meditations, iii, 11

Whatever happens at all . . . happens as it should (p. 115)

Consider that everything which happens, happens justly, and if thou observest carefully, thou wilt find it to be so.

Meditations, iv, 10

How much time he gains (p. 121)

How much trouble he avoids who does not look to see what his neighbour says or does or thinks, but only to what he does himself, that it may be just and pure;

Meditations, iv, 18

The Oldest Member says that he selected this quote at random. In fact, in Bartlett it appears only three entries after the previous quote.

The Long Hole (pp. 124–143)

“The Long Hole” was first published in August 1921 in the Strand Magazine (UK). Its first US appearance was in March 1922, in McClure’s Magazine.

Rule eight hundred and fifty-three (p. 124)

For some unfathomable reason, those responsible for the Rules of Golf have chosen to publish only the first 34 Rules; we can only speculate as to the matters addressed in the remaining 819 Rules.

happened to drop my niblick in the bunker (p. 124)

See p. 29. The modern rules make an exception if, provided nothing is done which constitutes testing the condition of the hazard, the player touches the ground as a result of or to prevent falling. It is debatable whether the accidental dropping of a club constitutes “testing the condition of the hazard.”

a reunion of Capulets and Montagues (p. 125)

The Capulets and Montagues are the two feuding Veronese families in Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. Romeo is the son of Montague, Juliet is Capulet’s daughter.

bring home the bacon (p. 126)

Idiom: deliver the desired result. See also Laughing Gas.

that bally boat of yours is a hazard (p. 131)

Actually, it’s not. The Rules of Golf now define a ‘hazard’ merely as “any bunker or water hazard”; when first defined, ‘hazard’ had a wider scope and encompassed

any bunker of whatever nature:— water, sand, loose earth, mole hills, paths, roads or railways, whins, bushes, rushes, rabbit scrape, fences, ditches or anything which is not the ordinary green of the course

Rule 15, 1891 ed.

but even that broad definition would have excluded Ralph’s boat.

nothing in the rules . . . against moving a hazard (p. 131)

The definition of “hazard” implies that a hazard is incapable of being moved, so Ralph’s point does not arise.

The boat is, in fact, an ‘obstruction’:

If any vessel, wheel-barrow, tool, roller, grass-cutter, box or similar obstruction has been placed upon the course, such obstruction may be removed. A ball lying on or touching such obstruction . . . may be lifted and dropped on the nearest point of the course, but a ball lifted in a hazard shall be dropped in the hazard.

Rule 17, 1891 ed.

It should be noted that, to avail himself of this “relief,” Ralph must drop his ball in the lake, thereby nullifying the advantage of the boat.

An important point is that the ball’s position is defined by reference to the spot on the ground above which it lies. If there is any change in this position, the ball is considered to have moved. Rule 18–2(i) provides that if, when the ball is in play, the player or his caddie causes it to move, the player shall incur a penalty stroke and the ball shall be replaced. By rowing the boat, Ralph is also moving his ball, in contravention of Rule 18–2(i).

While the Rules do not explicitly deal with this situation, there is a Decision on the Rules of Golf that covers a comparable situation. A golfer’s ball came to rest in a plastic bag, which was subsequently blown by the wind to another spot. It was ruled that “the player must drop the ball directly under the place where it originally lay in the bag.” In this case, it was further ruled that the ball was moved by the plastic bag, which constituted an ‘outside agency’ in terms of Rule 18–1, and that the player incurred no penalty. It is unlikely that the law-makers would view a boat rowed by Ralph as an ‘outside agency.’

Clothing the palpable (p. 133)

This quotation, from Act 1 scene i of Coleridge’s The Death of Wallenstein, appears in Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations, 10th ed, 1919.

I’ll give you five pounds to drive me (p. 136)

The arguments that applied to Ralph’s use of a boat apply equally to Arthur’s use of the motor car, which is also a movable obstruction.

against the rules to tamper with a hazard (p. 137)

Setting aside the issue of moving the ball, the car constitutes a movable obstruction and, as stated earlier, the Rules allow Arthur to lift his ball, remove the obstruction, and replace his ball (after cleaning it, should he so desire).

By now, if Arthur had taken the trouble to bone up on the rules of golf, he would have the game well and truly won!

A period of five minutes is allowed (p. 141)

The Rules do not, in fact, stipulate a time limit for playing the ball, the modern Rules stating merely that “The player shall play without undue delay . . .” (Rule 6–7)

The Rules do, however, define a ball as ‘lost’ if it is not “found or identified as his by the player within five minutes” after the player has begun to search for it. This five-minute time limit was introduced by the Aberdeen Golfers in 1783 and has remained unchanged since the R & A published its 1899 code.

If it is Ralph’s turn to play, Arthur cannot be said to be delaying play. And when it is his turn to play, the Rules have, since 1920, allowed him to play another ball (termed a ‘provisional ball’ in the modern Rule 27–2); in accordance with Rule 27–1, this ball shall be played “under penalty of one stroke, as nearly as possible at the spot from which the original ball was last played.” In Arthur’s case, this spot is located somewhere in the space previously occupied by the now-departed car.

Between 1891 and 1920, loss of ball meant loss of hole in match play, e.g.: “If a ball be lost, the player’s side shall lose the hole. A ball shall be held as lost if it be not found within five minutes after the search is begun.” (Rule 28, 1891 ed.)

I claim the match! (p. 141)

The Rules define ‘advice’ as “any counsel or suggestion which could influence a player in determining his play, the choice of a club or the method of making a stroke.” This definition has remained essentially unchanged since 1908.

Rule 8–1 states that “During a stipulated round, a player must not . . . (b) ask for advice from anyone other than his partner or either of their caddies.” Such a rule has been in place since 1858, when Rule 15 read: “A player must not ask advice about the game, by word, look, or gesture, from any one except his own caddie, his partner’s caddie, or his partner.”

In match play, the penalty for breach of this rule is loss of the hole.

I claim a draw! (p. 142)

Assuming that this single hole can be considered as a ‘stipulated round’, Arthur is correct. The match ended when Ralph forfeited the hole under Rule 8–1 (ignoring the many previous breaches of the rules by both players); Arthur is not obliged to take any action in relation to his ‘lost’ ball until it is his turn to play, which occurs after Ralph has already incurred the forfeit.

[If this seems odd, consider the situation — unlikely, but not impossible — in which the car containing Arthur’s ball re-appears within the five minutes allowed for searching for a ‘lost’ ball!]

Then we must consult St. Andrews (p. 143)

As well as reviewing the Rules of Golf very four years, the Rules Committees of the R&A and USGA also deal with queries arising from the Rules and publish their findings periodically in Decisions on the Rules of Golf.

The Heel of Achilles (pp. 144–161)

“The Heel of Achilles” was first published in November 1921 in the Strand Magazine (UK). In the US it made its first appearance in June 1922, simultaneously in the Chicago Tribune and St. Louis Globe-Democrat.

The title refers to Achilles, one of the Greek heroes in Homer’s Iliad. Achilles, the son of Peleus, King of the Myrmidons in Thessaly, is the leader of the Myrmidon army in the war against Troy. Following a quarrel with Agamemnon, the Greek commander-in-chief, Achilles withdraws to his camp and refuses to take any further part in the war, but, when the Trojans threaten to overrun the Greek camp, he allows his close friend, Patroclus, to lead the Myrmidons into battle. When Patroclus is killed by the Trojan hero, Hector, Achilles returns to the fight, routs the Trojans and kills Hector.

According to post-Homeric tradition, when Achilles was a child, his mother, Thetis, dipped him in the river Styx to make him invulnerable. But because the heel by which she held him remained dry, this was his one weak spot, as Achilles discovers when an arrow fired by Paris, the Trojan prince, strikes him in the heel and kills him; the death of Achilles is not described in the Iliad.

The ‘heel of Achilles’ now refers to any weak spot in an otherwise impregnable defence.

sixpence had dropped out (p. 144)

The coin is a sixpence in the Strand magazine and in the UK book; in the US newspaper appearance the coin is a quarter; in the US book Golf Without Tears the coin is a dime. The sixpence coin had a diameter of 19.41 mm (0.764 in); it was sterling silver before 1920 (92.5% Ag) and only 50% silver thereafter until 1946. The American quarter-dollar coin has a larger diameter of 24.257 mm (0.955 in) and at the time of this story was 90% silver. The American dime (one-tenth of a dollar) coin is smaller, at 17.91 mm (0.705 in) diameter as well as being much thinner.

At the time of writing in 1921, the exchange rate was US$3.85 to £1; dividing by 20 gives 19.25 cents to a sixpence, so the original “translation” to a quarter correctly used the coin that was closest in value.

Measuringworth.com suggests that using retail price indexes, that 1921 sixpence would have the purchasing power of £1.40 or $3.36 in 2023 terms.

marry early and often (p. 146)

The cynical slogan “Vote early and often” is thought to have been coined by William Hale Thompson, a notoriously corrupt politician who served as mayor of Chicago from 1915–23 and again from 1931–35.

See also Leave It to Psmith.

jumped off the dock (p. 146)

short-coating (p. 146)

Shortcoating was an important event in the lives of children in the 18th century. Very young children wore long robes, which extended well beyond the feet. By the time a child had begun to crawl and make its first attempts to walk, shorter, ankle-length skirted garments were necessary; the adoption of “short coats” was thus synonymous with the passage from crawling to walking.

Sandy McHoots won both British and American events (p. 148)

Sandy McHoots’s achievement has been ignored by golf’s historians, according to whom Robert T. Jones, in 1926, was the first golfer to win both the Open and US Open championships in the same year (though Harry Vardon was the first of many who have come close, winning the Open in 1898 and 1899 and the US Open in 1900). Since 1926, six players have achieved the double: Bobby Jones again in 1930, Gene Sarazen in 1932, Ben Hogan in 1953, Lee Trevino in 1971, Tom Watson in 1982, and Tiger Woods in 2000.

Time, the great healer (p. 156)

See Right Ho, Jeeves.

George Duncan (p. 161)

Duncan was born in 1887 at Oldmeldrum, Aberdeenshire. He came third in the Open Championship in 1910, but the First World War disrupted his career and he won his only Open title in 1920, the year that the event officially resumed after the war — he had tied Abe Mitchell in an unofficial Open Championship at St. Andrews a year earlier. Duncan helped to establish the Ryder Cup, and played in the event in 1927, 1929 (when he captained Great Britain to a win, routing the American captain, Walter Hagen, by 10 and 8 in a 36-hole match) and 1931.

Throgmorton Street (p. 161)

Throgmorton Street, in the City of London, is home to the London Stock Exchange.

the Rothschilds (p. 161)

The Rothschilds are one of the legendary banking dynasties. The family traces its origins to Frankfurt, from where, in the early years of the 19th century, the five sons of Mayer Amschel Rothschild set out to establish banking houses in London, Paris, Naples, Vienna, and Frankfurt itself. The Rothschild family continues to be a major force in finance and asset management, retaining personal control over a business empire that has grown up over more than two centuries.

The Rough Stuff (pp. 162–184)

“The Rough Stuff” was first published in October 1920 in the Chicago Tribune (US). Its first UK appearance was in April 1921, in the Strand Magazine.

The title is a play on ‘rough’, as used in a golfing context.

lovely woman loses in queenly dignity (p. 162)