Spring Fever

by

P. G. Wodehouse

Literary and Cultural References

This is part of an ongoing effort by the members of the Blandings Yahoo! Group to document references, allusions, quotations, etc. in the works of P. G. Wodehouse. These notes are by Neil Midkiff, with contributions from others as noted below.

Spring Fever was first published in the US by Doubleday and Company on 20 May 1948, and appeared in the UK on the same date published by Herbert Jenkins Ltd. A condensed “complete in one issue” version appeared after book publication in the Toronto Star Weekly of October 9, 1948, but that appearance has not been consulted for these notes.

Spring Fever was first published in the US by Doubleday and Company on 20 May 1948, and appeared in the UK on the same date published by Herbert Jenkins Ltd. A condensed “complete in one issue” version appeared after book publication in the Toronto Star Weekly of October 9, 1948, but that appearance has not been consulted for these notes.

The novel was originally written in 1943 while Wodehouse was in German-controlled Europe; it was reworked in the form of a play several times, including an American-set version which was not produced but became the source for the novel The Old Reliable.

As the two book editions appeared on the same date, it appears that editorial changes to each edition were made independently from the same typescript source. Each book has a mixture of typically American and typically British spelling, hyphenation, capitalization, and punctuation preferences, and neither is completely consistent internally in these regards. There are only a few instances of small differences in words and phrases, and these will be noted below as they appear.

Page references below are to the Doubleday US first edition, in which the text runs from p. 7 to p. 223.

Book One

Chapter 1

Great Neck (p. 7)

With the success of his Princess Theatre productions, Wodehouse had bought a house in Great Neck on Long Island, New York, in 1918; the property was on three acres and had a tennis court.

Pennsylvania terminus (p. 7)

Better known as Penn Station, this railroad station in midtown Manhattan serves intercity (Amtrak) rail lines in the Northeast Corridor as well as commuter rail services of New Jersey Transit and the Long Island Rail Road. The original Beaux-Arts building completed in 1910 was demolished in 1963, but the underground rail platforms with connections to seven rail tunnels and to the New York City subway system continue to make up the busiest transport facility in the Western Hemisphere.

G. Ellery Cobbold (p. 7)

Wodehouse often titles his American characters, especially rich ones, with names beginning with an initial for the first name and a spelled-out middle name. This is not exclusively an American naming habit, but in his fiction I count thirty Americans, nine Englishmen, two golfers who could be either, and two Frenchmen who use their first initial and middle name.

bock beer (p. 7)

A strong dark variety of German beer. This seems to be its only mention so far found in Wodehouse.

looked like a cartoon of Capital in a labor paper (p. 7)

The UK edition has in a labour paper here.

With the soup, some one who looked like a cartoon of Capital in a Socialistic paper said he was glad to see that Westinghouse Common were buoyant again.

The Small Bachelor, ch. 3.1 (1926/27)

And, as we did so, a harsh, metallic voice called his name, and I perceived, standing at some little distance, a beetle-browed man of formidable aspect, who looked like a cartoon of Capital in a Labour paper.

“Excelsior” (1948; in Nothing Serious, 1950)

“You don’t know Roscoe, do you? He looks like a cartoon of Capital in the Daily Worker.”

Something Fishy/The Butler Did It, ch. 9 (1957)

buck-and-wing dance (p. 7)

See Money in the Bank.

counted his blessings one by one (p. 7)

Several popular spiritual songs and hymns have similar phrases, but given the 1948 date of this novel, the most likely source is “Count Your Blessings” with lyrics by Edith Temple and music by Reginald Morgan. A 1948 recording sung by Josef Locke can be heard at Second Hand Songs online.

golf handicap was down to twenty-four (p. 7)

Frequently mentioned in Wodehouse’s golf stories as the level of proficiency of earnest but unsuccessful strivers after golfing skill. See A Glossary of Golf Terminology for how a handicap is used in golf.

Consolidated Nail File and Eyebrow Tweezer Corporation of Scranton, Pa. (p. 7)

contesting the final of the Office Boys’ High-Kicking Championship against a willowy youth from the Consolidated Eyebrow Tweezer and Nail File Corporation.

Sam In the Suburbs/Sam the Sudden, ch. 1 (1925)

“you may some day, like me, become Third Assistant Vice-President of the Schenectady Consolidated Nail-File and Eyebrow-Tweezer Corporation.”

“Jeeves and the Yule-Tide Spirit” (1927; in Very Good, Jeeves, 1930)

Debrett’s Peerage (p. 7)

Meadowes, his man (p. 9)

See Young Men in Spats.

Beevor Castle, Kent (p. 9)

See the second paragraph under Belpher in A Damsel in Distress.

a son, Lord Beevor (p. 9)

As the only son of an earl, Tony Cobbold is given by courtesy one of his father’s subsidiary titles, Viscount Beevor, and is addressed as “Lord Beevor.” He remains offstage in this book but is referenced as the brother of Lord Shortland’s daughters.

Hands-Across-the-Sea (p. 10)

See Meet Mr. Mulliner.

Grover Whalen’s moustache (p. 10)

Grover Whalen (1886–1962), a politician and businessman in New York City, was instrumental in developing transportation and public works in the city, and in addition to other public duties was for many years the city’s official greeter to distinguished guests, in which capacity his moustached face became familiar to the public as he was photographed with many celebrities.

Grover Whalen (1886–1962), a politician and businessman in New York City, was instrumental in developing transportation and public works in the city, and in addition to other public duties was for many years the city’s official greeter to distinguished guests, in which capacity his moustached face became familiar to the public as he was photographed with many celebrities.

My son Joshu-ay (p. 11)

A slightly different version of this 1907 lyric by Benjamin Hapgood Burt is quoted by Sigmund Spaeth in Read ’Em and Weep: The Songs You Forgot to Remember (1927). The melody of the song is transcribed there, under the title “Wal, I Swan!” The full sheet music is online at the University of Maine.

life is stern and earnest (p. 11)

See Ukridge for the Longfellow poem alluded to here.

not put into this world for pleasure alone (p. 11)

apple-pie order (p. 11)

Perfectly tidy and neat. The phrase is of uncertain origin, cited from 1780 onward in the OED. Not to be confused with an apple-pie bed, which seems to be in order but is unusable: see Summer Lightning.

Spelled applepie order in the UK first edition.

perfecto (p. 12)

A large thick cigar tapered at each end.

spanner (p. 12)

See Leave It to Psmith.

celluloid circles (p. 12)

From the flexible clear plastic (cellulose nitrate) then used as the base for motion-picture film, the term began to be used figuratively for the world of the cinema as early as 1916. This sentence from Wodehouse is cited in the OED as another example of its usage as an adjective.

alarm and … despondency (p. 12)

See Ukridge.

spaghetti Caruso (p. 12)

A favorite of opera singer Enrico Caruso, the rich sauce for this pasta dish is based on tomatoes and tomato paste, chicken livers, and mushrooms, with herbs, spices, oil, butter, and cheese.

sensitive plant (p. 12)

See Right Ho, Jeeves.

the bone extended to his head (p. 12)

Compare bone-headed in Bill the Conqueror.

sleeve across the windpipe (p. 12)

See The Mating Season.

ingrowing incompatibility (p. 12)

Though it was widely believed in England that Americans could separate or divorce on practically any grounds, this was possible but rare; from 1887 to 1906, of nearly a million divorces, only 389 were granted solely on grounds of incompatibility of temper. Even so, nearly all states tightened their statutes to eliminate this basis over the succeeding decade or so.

slathers of alimony (p. 12)

See Money for Nothing.

think on his feet (p. 12)

To react to events readily and quickly; the OED cites Wodehouse in The Luck of the Bodkins, ch. 16, in which a note from Lottie Blossom has the postscript “Think on your feet, boy!”

do it now (p. 12)

See Leave It to Psmith.

gentlemen’s personal gentlemen (p. 13)

More commonly known as manservants or valets. This orotund phrasing is best known as the self-description of Jeeves; see for instance “Without the Option” (1925).

his current account (p. 14)

His bank balance; his funds available for immediate payment, as opposed to longer-term investments.

letters of fire (p. 14)

See also letters of flame in Summer Moonshine.

For before his eyes in letters of fire there seemed to be written the one word GALLAGHER.

The Small Bachelor, ch. 13 (1927)

As clearly as if the information had been written in letters of fire on the wall of the boudoir she saw behind this superfluity of Whipples the hand of her brother Galahad.

Galahad at Blandings, ch. 9.1 (1965)

Every detail of it was imprinted on his memory in letters of fire.

“Life with Freddie” (in Plum Pie, 1967)

Chapter 2

Bloxham House (p. 15)

See Uncle Fred in the Springtime.

a face like that of an amiable hippopotamus (p. 17)

See Something Fishy.

across the Sands of Dee (p. 17)

See Sam the Sudden.

‘The day of retribution is at hand … when there will be wailing and gnashing of teeth.’ (p. 18)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

clobber (p. 18)

Slang for clothes, first cited in the OED from British sources in 1879.

the hand which he had placed on the top of his head to prevent it coming off (p. 19)

It was the husky voice of one who has wandered far and long across the hot sands, the voice of a man delicately endeavoring to keep the top of his head from coming off.

Bill the Conqueror, ch. 2.1 (1924)

Her eye resembled the eye of one of the more imperious queens of history; and when she laughed strong men clutched at their temples to keep the tops of their heads from breaking loose.

Agnes Flack in “Those in Peril on the Tee” (1927; in Mr. Mulliner Speaking, 1929/30)

He shouted. It was an injudicious move. The top of his head did not actually come off, but it was a very near thing. By a sudden clutch at both temples he managed to avert disaster in the nick of time, and tottered weakly to the bed.

Money for Nothing, ch. 11.1 (1928)

With an effort Packy contrived to bring his mind to bear on the question. The strain of this made him feel as if the top of his head had worked loose.

Hot Water, ch. 16.4 (1932)

The result was that after about two minutes of intense concentration, during which he felt several times as if the top of his head were coming off, an idea suddenly shot out of the welter like a cork from the Old Faithful geyser.

Heavy Weather, ch. 8 (1933)

For some moments she spoke with an incisive eloquence which made Tubby feel as if the top of his head had come off.

Summer Moonshine, ch. 1 (1937)

It caught him squarely between the eyes, creating the momentary illusion that the top of his head had parted from its moorings.

Money in the Bank, ch. 5 (1942)

And Bingo was just drawing a deep breath before starting in to explain to her in moving words just how much this Darts tournament mattered to him, when the top of his head suddenly came off and shot up to the ceiling. That is to say, he felt as if it had done so.

“The Shadow Passes” (in Nothing Serious, 1950)

He also wished that the top of his head would stop going up and down like the lid of a kettle, for this interfered with clear thought.

Barmy in Wonderland, ch. 11 (1952)

It had sometimes happened to Bill, when indulging in his hobby of amateur boxing, to place the point of his jaw in a spot where his opponent was simultaneously placing his fist, and the result had always been a curious illusion that the top of his head had parted abruptly from its moorings.

Something Fishy, ch. 13 (1957)

both Jerry and Lionel Spenser leaped several inches from the ground, each suffering a passing illusion that the top of his head had broken loose from its moorings.

Frozen Assets, ch. 10.3 (1964)

And he was about to grope in the darkness in the hope of finding the door, when a voice spoke, a harsh, guttural voice which jarred unpleasantly on his sensitive ear, though the most musical voice speaking at that moment would equally have given him the illusion that the top of his head had parted from its moorings.

“A Good Cigar Is a Smoke” (1967; in Plum Pie)

With both hands pressed to the top of my head to prevent it from taking to itself the wings of a dove and soaring to the ceiling, I was asking myself what the harvest would be.

Aunts Aren’t Gentlemen, ch. 19 (1974)

Compare also:

For some time after life had returned to the rigid limbs Tipton sat with his head between his hands, the better to prevent it floating away from the parent neck.

Galahad at Blandings, ch. 1 (1965)

your good angel (p. 19)

Wodehouse had titled a 1910 story “The Good Angel”.

weskit (p. 19)

The traditional British pronunciation of “waistcoat”; now only a dialect variation.

barstard (p. 19)

A phonetic spelling here; see The Girl in Blue.

stinko (p. 20)

Heavily drunk; originally US slang. The OED has citations from 1927 onward and quotes Wodehouse’s usage in Laughing Gas, ch. 9 (1936).

giving ’em the raspberry (p. 20)

See The Girl on the Boat.

Let your Yea be Yea and your Nay be Nay, as the Good Book says. (p. 21)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

Barribault’s Hotel (p. 21)

See Ice in the Bedroom.

pip emma (p. 21)

In the afternoon; p.m. From the syllables used in Royal Air Force communications when spelling out abbreviations.

white-hot rivets into his skull (p. 21)

There for some minutes he remained while unseen hands drove red-hot rivets into his skull.

Money for Nothing, ch. 9.1 (1928)

the course of true love (p. 22)

Alluding to A Midsummer Night’s Dream; see Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse for the passage and other references to it.

fading out on the clinch (p. 22)

Cinematic jargon for ending a movie with a couple embracing. Compare slow fade-out on the embrace in Bill the Conqueror.

blows the All Clear (p. 23)

Originally, sounded an audible signal of the end of a wartime air raid. In London during the First World War, Boy Scout buglers were used to blow the all-clear; sirens were used in the Second World War.

cloth-headed (p. 24)

See Money in the Bank.

in the Good Book, where the feller said ‘Go’ and they goeth (p. 24)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

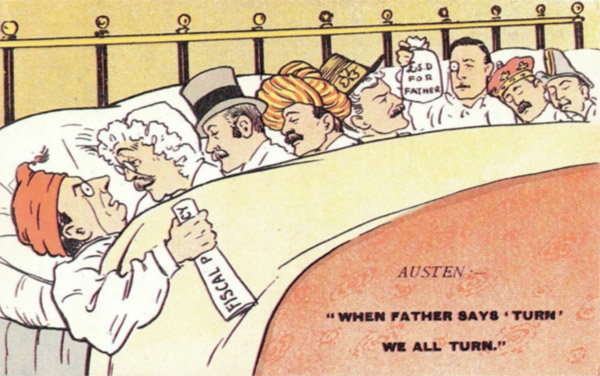

when Father says ‘Turn,’ we all turn (p. 24)

Referring to a political cartoon of 1905; Austen Chamberlain was Chancellor of the Exchequer, and his father Joseph Chamberlain, no longer in the Cabinet, was advocating Tariff Reform.

Referring to a political cartoon of 1905; Austen Chamberlain was Chancellor of the Exchequer, and his father Joseph Chamberlain, no longer in the Cabinet, was advocating Tariff Reform.

“In England when Comrade Jackson says ‘Turn’ we all turn.”

Psmith, Journalist, ch. 5 (1909/15)

an am-parce (p. 24)

Augustus Robb is attempting the French pronunciation of impasse.

one of those stately homes of England they talk about (p. 24)

See Heavy Weather.

heliotrope (p. 24)

See Thank You, Jeeves.

Chapter 3

fifth Earl of Shortlands (p. 25)

An Earl is a member of the British peerage, ranking below a Marquess and above a Viscount; an Earl has the title “Earl of” when the title originates from a place name. [JD]

two shillings and eightpence (p. 25)

In decimal terms, this is 0.1333… pounds sterling. The Bank of England inflation calculator suggests a factor of about 29 to account for consumer price inflation from 1948 to early 2023, so this would be the rough equivalent of £3.85 in modern terms.

The sun … was shining (p. 25)

Wodehouse made a specialty of using the sun’s rays to begin a book or to introduce the reader to a new scene. See also the opening of Chapter 19, p. 177 below. A sampling:

Sunshine, streaming into his bedroom through the open window, woke Garnet next day as distant clocks were striking eight. It was a lovely morning, cool and fresh. The grass of the lawn, wet with dew, sparkled in the sun.

Love Among the Chickens, ch. 5 (1906)

The sun shone gaily on the white-walled houses, the bright Gardens, and the two gleaming casinos.

“Ruth in Exile” (1912)

The sunshine of a fair spring morning fell graciously on London town. Out in Piccadilly its heartening warmth seemed to infuse into traffic and pedestrians alike a novel jauntiness, so that bus drivers jested and even the lips of chauffeurs uncurled into not unkindly smiles.

Something Fresh/Something New, ch. 1.1 (1915)

London brooded under a gray sky. There had been rain in the night, and the trees were still dripping. Presently, however, there appeared in the laden haze a watery patch of blue; and through this crevice in the clouds the sun, diffidently at first but with gradually increasing confidence, peeped down on the fashionable and exclusive turf of Grosvenor Square. Stealing across the square its rays reached the massive stone walls of Drexdale House, until recently the London residence of the earl of that name; then, passing through the window of the breakfast room, played lightly on the partially bald head of Mr. Bingley Crocker, late of New York, in the United States of America, as he bent over his morning paper. Mrs. Bingley Crocker, busy across the table reading her mail, the rays did not touch. Had they done so, she would have rung for Bayliss, the butler, to come and lower the shade, for she endured liberties neither from man nor from Nature.

Piccadilly Jim, ch. 2 (1917)

The sun that had shone so brightly on Belpher Castle at noon, when Maud and Reggie Byng set out on their journey, shone on the west end of London with equal pleasantness at two o’clock. … On all these things the sun shone with a genial smile.

A Damsel in Distress, ch. 1.2 (1919)

Through the curtained windows of the furnished apartment which Mrs. Horace Hignett had rented for her stay in New York, rays of golden sunlight peeped in like the foremost spies of some advancing army.

Three Men and a Maid/The Girl on the Boat, ch. 1 (1922)

The little town of Market Blandings was a peaceful sight as it slept in the sun.

Leave It to Psmith, ch. 10.3 (1923)

Tilbury Street … stewed in the sunshine …. The pavement in front of Tilbury House was all inlaid with patines of bright gold.

Bill the Conqueror, ch. 10.1 (1924)

The sun of a fair summer afternoon shone upon St. Mary Axe.

Bill the Conqueror, ch. 21 (1924)

The sun, whose rays had roused Sergeant-Major Flannery from his slumbers at Healthward Ho that morning, had not found it necessary to perform the same office for Lester Carmody at Rudge Hall.

Money for Nothing, ch. 14.1 (1928)

Blandings Castle slept in the sunshine. Dancing little ripples of heat-mist played across its smooth lawns and stone-flagged terraces.

Summer Lightning, ch. 1.1 (1929)

The sun shone bravely down. And it cannot but assist readers of this chronicle if, in pursuance of his tested policy of pausing from time to time to offer a bird’s-eye view of affairs to his patrons, the historian gives here a list of the more interesting objects on which it shone.

Hot Water, ch. 12 (1932)

The sunlight poured into the small morning room of Chuffnell Hall. It played upon me, sitting at a convenient table; on Jeeves, hovering in the background; on the skeletons of four kippered herrings; on a coffeepot; and on an empty toast rack.

Thank You, Jeeves, ch. 22 (1934)

The day on which Lawlessness reared its ugly head at Blandings Castle was one of singular beauty. The sun shone down from a sky of cornflower blue, and what one would really like would be to describe in leisurely detail the ancient battlements, the smooth green lawns, the rolling parkland, the majestic trees, the well-bred bees and the gentlemanly birds on which it shone.

“The Crime Wave at Blandings” (1937)

It was a glorious morning of blue and gold, of fleecy clouds and insects droning in the sunshine.

Summer Moonshine, ch. 1 (1937)

The month was August, and from a cloudless sky the sun blazed down on the popular seashore resort of East Bampton, illuminating with its rays the beach, the pier, the boardwalk, the ice-cream stands, the hot doggeries and the simmering ocean.

“Feet of Clay” (in Nothing Serious, 1950)

The sunshine which is such an agreeable feature of life in and around Hollywood, when the weather is not unusual, blazed down from a sky of turquoise blue on the spacious grounds of what, though that tempestuous Mexican star had ceased for nearly a year to be its owner and it was now the property of Mrs. Adela Shannon Cork, was still known locally as the Carmen Flores place. The month was May, the hour noon.

The Carmen Flores place stood high up in the mountains at the point where Alamo Drive peters out into a mere dirt track fringed with cactus and rattlesnakes, and the rays of the sun illumined its swimming pool, its rose garden, its orange trees, its lemon trees, its jacaranda trees and its stone-flagged terrace. Sunshine, one might say, was everywhere, excepting only in the heart of the large, stout, elderly gentleman seated on the terrace, who looked like a Roman emperor who had been doing himself too well on starchy foods and forgetting to watch his calories.

The Old Reliable, ch. 1 (1951)

The sunshine of a fine summer morning was doing its best for the London suburb of Valley Fields, beaming benevolently on its tree-lined roads, its neat little gardens, its rustic front gates and its soaring television antennae.

Something Fishy, ch. 2 (1957)

The morning sun shone down on Blandings Castle, and the various inmates of the ancestral home of Clarence, ninth Earl of Emsworth, their breakfast digested, were occupying themselves in their various ways.

Service With a Smile, ch. 1 (1961)

The afternoon sun poured brightly into the office of the manager of Guildenstern’s Stores, Madison Avenue, New York, but there was no corresponding sunshine in the heart of Homer Pyle, the eminent corporation lawyer, as he sat there.

The Girl in Blue, ch. 1 (1970)

As always when the weather was not unusual the Californian sun shone brightly down on the Superba-Llewellyn motion-picture studio at Llewellyn City.

Pearls, Girls and Monty Bodkin/The Plot That Thickened, ch. 1 (1972)

where the family lived and had their being (p. 25)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

heebie-jeebies (p. 28)

See Hot Water.

slings and arrows of outrageous Fortune (p. 28)

From Hamlet; see Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse.

favourite hat (p. 28)

Spelled in the British manner in both US and UK book.

“Lady Constance has pinched his favourite hat and given it to the deserving poor, and he lives in constant fear of her getting away with his shooting jacket with the holes in the elbows.”

Lord Ickenham speaking of Lord Emsworth in Service With a Smile, ch. 2.3 (1961)

Walham Green (p. 28)

The historic name of a former English village, now part of the London borough of Hammersmith and Fulham. The former Walham Green tube station was renamed Fulham Broadway in 1952.

kitchenmaid … scorched-earth policy (p. 28)

“He was looking forward gloomily to a dinner cooked by the kitchen maid, who, though a girl of many sterling merits, always adopts the scorched earth policy when preparing a meal, and you know what his digestion’s like.”

Stiff Upper Lip, Jeeves, ch. 17 (1963)

Bradstreet raises his hat (p. 28)

Figuratively speaking, Topping’s financial status is top-notch. John M. Bradstreet (1815–1863) was the American founder of a credit-rating firm, which merged in 1933 with Dun & Co. to form today’s Dun & Bradstreet.

to sink for the third time (p. 29)

King Lear (p. 29)

See Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse for more references to the title character of the Shakespeare play.

turned his face to the wall (p. 29)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

“Whose is this, Father?” (p. 29)

The US edition capitalizes Lady Adela’s “Father” throughout; the UK edition inconsistently lowercases this and many other instances, but not all of them, leading me to believe that the US edition may be closer to Wodehouse’s original typescript.

stamp album (p. 29)

Another valuable stamp album plays a pivotal role in “Anselm Gets His Chance” (1937; in Eggs, Beans and Crumpets, 1940).

to break Commandments (p. 30)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

a tentative prod with the tip of his finger (p. 30)

The UK first edition has fingers here, probably a misprint since tip is singular in both editions.

Stanley Gibbons (p. 30)

A London firm dealing in collectible postage stamps, catalogues, magazines, and so forth; founded in 1856 by Edward Stanley Gibbons (1840–1913).

great open spaces (p. 31)

See Leave It to Psmith.

Roget … Thesaurus (p. 31)

See Summer Moonshine.

on a salver (p. 31)

See Leave It to Psmith.

a tithe (p. 32)

Here, simply one-tenth, with no religious connotations.

with the air of an ambassador about to deliver important dispatches (p. 32)

Spelled despatches in the UK first edition.

Vosper withdrew like an ambassador who has received his papers…

“Keeping In with Vosper” (1926)

The butler withdrew, rather in the manner of an ambassador who has delivered a protocol—or whatever it is that ambassadors do deliver.

If I Were You, ch. 1 (1931)

Silversmith came navigating over the threshold. This majestic man always had in his deportment a suggestion of the ambassador about to deliver important state papers to a reigning monarch, and now the resemblance was heightened by the fact that in front of his ample stomach he was bearing a salver with a couple of telegrams on it.

The Mating Season, ch. 13 (1949)

soda-water syphon (p. 34)

A bottle for dispensing carbonated water; pressing a lever or button opens a valve, so that the pressure of the gas forces soda water out of the bottle’s spout into the user’s drinking glass.

having delivered the important despatches without dropping them (p. 34)

Here both the US and UK editions use the spelling despatches.

The burned child fears the fire (p. 34)

See The Girl in Blue.

slough of despond (p. 35)

A deep bog that has to be crossed in John Bunyan’ Pilgrim’s Progress, part 1, to get to the Wicket Gate. [MH]

contending in the lists of love (p. 35)

Here, in the lists refers to the space enclosed by barriers within which a jousting tournament was held, or figuratively to any scene of contest or combat.

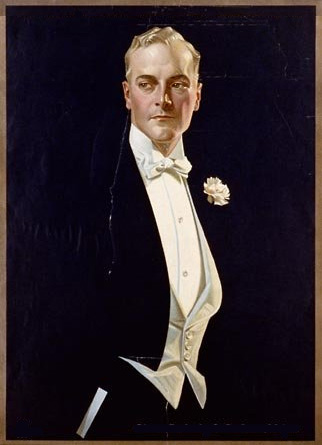

a collar advertisement (p. 35)

Perhaps a bit out of date by 1948, this refers to the era when shirts and collars were sold separately, and were attached by buttons or studs to each other. The collar could be changed daily to maintain a fresh look, and since it was more visible than the shirt, its style could be advertised separately and kept up with the prevailing fashion. In the USA, the most widely advertised brand was the Arrow collar made by Cluett, Peabody and Co., who used a series of models dubbed the Arrow Collar Man in ads from 1907 to 1931, such as the image at right painted by J. C. Leyendecker.

Perhaps a bit out of date by 1948, this refers to the era when shirts and collars were sold separately, and were attached by buttons or studs to each other. The collar could be changed daily to maintain a fresh look, and since it was more visible than the shirt, its style could be advertised separately and kept up with the prevailing fashion. In the USA, the most widely advertised brand was the Arrow collar made by Cluett, Peabody and Co., who used a series of models dubbed the Arrow Collar Man in ads from 1907 to 1931, such as the image at right painted by J. C. Leyendecker.

some days in the water (p. 35)

A variant of a cliché of journalism; see The Inimitable Jeeves.

Chapter 4

Eric Blore (p. 36)

English actor Eric Blore (1887–1959) is now probably best known for his appearances in the Fred Astaire/Ginger Rogers films Flying Down to Rio, The Gay Divorcee, Top Hat, Swing Time, and Shall We Dance, but he had a long stage career beginning in London, including being in the cast of Nuts and Wine, a 1914 revue written by Wodehouse and C. H. Bovill. He played a variety of roles but made a specialty of playing butlers, valets, waiters, and other servants with a comically philosophic turn of phrase. He was short, balding, and somewhat tubby. I can’t help thinking that Albert Peasemarch in The Luck of the Bodkins was written with the idea that Blore might play the part in a dramatized version.

English actor Eric Blore (1887–1959) is now probably best known for his appearances in the Fred Astaire/Ginger Rogers films Flying Down to Rio, The Gay Divorcee, Top Hat, Swing Time, and Shall We Dance, but he had a long stage career beginning in London, including being in the cast of Nuts and Wine, a 1914 revue written by Wodehouse and C. H. Bovill. He played a variety of roles but made a specialty of playing butlers, valets, waiters, and other servants with a comically philosophic turn of phrase. He was short, balding, and somewhat tubby. I can’t help thinking that Albert Peasemarch in The Luck of the Bodkins was written with the idea that Blore might play the part in a dramatized version.

Robert Taylor (p. 36)

Robert Taylor (p. 36)

American actor, born Spangler Arlington Brugh (1911–1969); in films from 1934, and later a television star and host. Famously handsome, which is why he is mentioned here.

bearing Youth like a banner (p. 36)

He would have been hard to please who had not been attracted by Sally. … And she carried Youth like a banner.

The Adventures of Sally, ch. 1.1 (1921/22)

Murder at some dashed place or other (p. 36)

Perhaps Murder at Murslow Grange, mentioned in Chapter 19 (p. 183 of US edition).

For dashed see A Damsel in Distress.

the City (p. 37)

See Leave It to Psmith.

Harrogate (p. 38)

Harrogate is a spa town in Yorkshire, renowned for its mineral waters, both for drinking and bathing, as a “cure” for the aftereffects of rich living.

lumbago (p. 38)

Pain in the muscles of the lower back.

a bird in a gilded cage (p. 38)

Alluding to a very popular sentimental ballad from 1900, “A Bird in a Gilded Cage” by Arthur J. Lamb and Harry Von Tilzer, about a woman who has married for money instead of love.

cross-talk act (p. 38)

A comic routine for two performers, with rapid-fire puns and jokes, and usually some slapstick comedy as well.

graven on his heart (p. 39)

See Bill the Conqueror.

straight from the horse’s mouth (p. 40)

Inside information, as if a racetrack tip were communicated by the horse itself.

sturdy oak (p. 40)

“Besides, what a young and inexperienced girl needs is a man of weight and years to lean on. The sturdy oak, not the sapling.”

“Indian Summer of an Uncle” (1930; in Very Good, Jeeves)

Captain Coe’s Final Selection (p. 40)

“Captain Coe” was the pseudonym of the sporting editor of The Sketch, who included tips on horses he thought likely to run well.

And with that the New Asiatic Bank staff of messengers dismissed Mr. Bickersdyke and proceeded to concentrate themselves on their duties, which consisted principally of hanging about and discussing the prophecies of that modern seer, Captain Coe.

Psmith in the City, ch. 10 (serialized as “The New Fold”, 1908/10)

“He is Our Newmarket Correspondent’s Five-Pound Special and Captain Coe’s final selection.”

“Came the Dawn” (1927)

second vice-president (p. 43)

“What! The little chap who looks like the second vice-president of something?”

Ernest Plimlimmon in “There’s Always Golf!” (1936; in Lord Emsworth and Others, 1937)

a touch (p. 43)

Not being touched on the shoulder, but being asked for a loan of money. See Uncle Fred in the Springtime.

stag at bay (p. 43)

See under Landseer at Right Ho, Jeeves.

joint account (p. 44)

A bank account that can be drawn upon by both husband and wife, meaning that neither can have any financial secret from the other. Plum and Ethel Wodehouse had this sort of account, and he mentions it in a few books, most explicitly:

‘I am not able to write a cheque for the smallest amount without having my wife ask “What the hell was this for?” and there is nothing that hampers and shackles a man more.’

Ivor Llewellyn in Pearls, Girls and Monty Bodkin, ch. 3 (1972)

Catherine of Russia (p. 44)

See Money for Nothing.

“I saw her first lunching at the Plaza with a woman who looked like Catherine of Russia. Her mother, no doubt.”

George Finch speaking of Mrs. Waddington in The Small Bachelor, ch. 1.3 (1927)

She was no Cleopatra, no Catherine of Russia—just a slim, slight girl with a tip-tilted nose.

Pat Wyvern in Money for Nothing, ch. 4.1 (1928)

“Lots of the world’s most wonderful women would be out of place in Woollam Chersey. Queen Elizabeth—Catherine of Russia—Cleopatra—dozens of them.”

Doctor Sally, ch. 3 (1932)

She was a large, hearty-looking woman in the early forties, built on the lines of Catherine of Russia, and her eyes, which were blue and bright and piercing, were obviously in no need of glasses.

Leila Yorke in The Ice in the Bedroom, ch. 4 (1961)

buff sheet of paper (p. 44)

A telegram.

bally (p. 45)

crust (p. 45)

See under rind in Something Fresh.

“You’re behind the times, Shorty,” said Terry. “Barribault’s is the posh place now.” (p. 49)

One of the few significant differences in wording between the US and UK editions. The UK first edition reads:

“You’re off the beat, Shorty,” said Terry. “Barribault’s is Stanwood’s stamping ground.”

Gaspard the miser (p. 48)

The villain in the French operetta Les Cloches de Corneville, which was a hit in Paris in 1877. It had one season in London in 1878 under the title The Chimes of Normandy. [NTPM]

off his bally onion (p. 48)

See Sam the Sudden.

founder of the feast (p. 48)

Reminiscent of Bob Cratchit’s toast to Mr. Scrooge in A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens.

Belshazzar’s Feast (p. 48)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

angel could have descended from on high (p. 48–49)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

Black Hand (p. 49)

See Hot Water.

manna in the wilderness (p. 49)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

V.C. (p. 49)

The Victoria Cross, the highest British award for military valor.

jimmy-o’-goblins (p. 49)

Outdated rhyming slang for sovereigns: gold coins worth one pound sterling featuring an image of the current monarch.

Chapter 5

oomph (p. 50)

Here, meaning energy or vigor; also used in Hollywood for romantic attractiveness, as with actress Ann Sheridan, dubbed the “Oomph Girl” in the 1940s.

Wodehouse first used this word as the spelling of a sobbing sound (Lottie Blossom in ch. 11 of The Luck of the Bodkins, 1935). His first use of it in the romantic sense seems to be in Joy in the Morning, ch. 6 (1946):

Well, I could readily understand Boko falling in love at first sight with Nobby, of course, for she is a girl liberally endowed with oomph.

Wodehouse’s other uses are also in this vein, as with Corky Pirbright in The Mating Season and Bobbie Wickham in Jeeves in the Offing.

ministering angel (p. 51)

Nearly all of Wodehouse’s frequent uses of this phrase refer to women in their capacity to comfort or nurse, whether with or without an explicit reference to the lines from Sir Walter Scott (see Heavy Weather). This is one of only two references so far found where the angel is masculine; the other is between the Vanringham brothers:

Joe shook his head.

“I’m sorry, Tubby. I want to be a ministering angel, but I can’t follow the plot.”

Summer Moonshine, ch. 8 (1937)

Aloysius McGuffy (p. 51)

The name may possibly have been influenced by the real-life Malachy McGarry, bartender at Buck’s Club in London from 1919 to 1941, mentioned as himself in “Scoring Off Jeeves” (1922) and in a few later stories as the bartender at the Drones Club. [Thanks to NTPM.]

large, flat hand … “Wasp.” (p. 52)

Wasps are often mentioned in Wodehouse, but only a few times are they squashed upon another person.

Wallace walked to the tee. As he did so, he was startled to receive a resounding smack.

“Sorry,” said Peter Willard, apologetically. “Hope I didn’t hurt you. A wasp.”

And he pointed to the corpse, which was lying in a used-up attitude on the ground.

“Afraid it would sting you,” said Peter.

“Oh, thanks,” said Wallace.

He spoke a little stiffly, for Peter Willard had a large, hard, flat hand, the impact of which had shaken him up considerably.

“The Magic Plus Fours” (1922; in The Heart of a Goof, 1926)

A Tankard of Stout had just squashed a wasp as it crawled on the arm of Miss Postlethwaite, our popular barmaid, and the conversation in the bar-parlour of the Angler’s Rest had turned to the subject of physical courage.

“Monkey Business” (1932; in Blandings Castle and Elsewhere, 1935)

base over apex (p. 54)

See Cocktail Time.

said ‘Come’ and they goeth (p. 55)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

caged skylark (p. 55)

Probably alluding to “The Caged Skylark” (1879, published posthumously) by Gerard Manley Hopkins (1844–1889). Both such a bird and “man’s mounting spirit” “wring their barriers in bursts of fear or rage” according to Hopkins.

piece of cheese (p. 55)

See Hot Water.

sticking … like a poultice (p. 55)

A pasty, soft medicine applied to the skin in a warm, moist condition, usually with a bandage or dressing.

toad beneath the harrow (p. 56)

“Look, look, lookie, here comes cookie!” (p. 56)

A slight misquotation of a 1935 song by Mack Gordon: see SecondHandSongs.

Kempton Park (p. 57)

See A Damsel in Distress.

in the bag (p. 57)

See Hot Water.

“I’m fifty-two today” (p. 58)

A take-off on “I’m Twenty-One Today”; see A Damsel in Distress.

“Crikey!” (p. 58)

A euphemistic substitute oath, used instead of swearing by the name of Christ. An originally British colloquialism cited in the OED since 1826.

what the deuce (p. 59)

Another substitution, here to avoid mentioning the Devil by name.

ships that pass in the night (p. 59)

See A Damsel in Distress for the Longfellow poem alluded to here.

restorative (p. 59)

See Sam the Sudden.

Chapter 6

stung for five (p. 59)

Approached with a request to borrow five pounds.

out in Kenya, growing coffee (p. 60)

At the time, a British colony in Africa; it became an independent nation in 1963. References to it in Wodehouse are few.

“Immediately after the ceremony we are going off somewhere to make our fortune. Kenya is a spot we are considering. Planting coffee, you know.”

If I Were You, ch. 21 (1931)

A clerk named Simmons was called in and ordered to have a go, but he resigned and is now coffee-planting in Kenya.

“About This Book” in Louder and Funnier (1932)

It was a confusion of ideas between him and one of the lions he was hunting in Kenya that had caused A. B. Spottsworth to make the obituary column.

Ring for Jeeves, ch. 1 (1953) / The Return of Jeeves, ch. 5 (1954)

Two editors named Schwed and Goodman were called in and told to have a go, but after a couple of pages both resigned and are now coffee-planting in Kenya.

America, I Like You, ch. 1.3 (1956)

the doctor’s daughter, betrothed to a chap who’s planting coffee in Kenya

Listed among the female population of Dovetail Hammer in Cocktail Time, ch. 7 (1958)

“…I got that letter from Boddington. Pal of mine in Kenya,” Freddie explained. “Runs a coffee ranch or whatever you call it out there.”

Ice in the Bedroom, ch. 1 (1961)

superstructure (p. 60)

See Piccadilly Jim.

turns up slightly at the tip (p. 61)

See A Damsel in Distress.

chump chops (p. 61)

Lamb chops cut from the rump of the lamb.

“When you get Stanwood, you’ve got something.” (p. 62)

“Earls are hot stuff. When you get an earl, you’ve got something.”

Lord Ickenham in “Uncle Fred Flits By” (1935; in Young Men in Spats, 1936)

“And when you get the best in Frederick Altamont Cornwallis, fifth Earl of good old Ickenham, you’ve got something.”

Uncle Dynamite, ch. 4 (1948)

“When you get a wife, I often say, you’ve got something.”

Lord Ickenham in Cocktail Time, ch. 2 (1958)

“And when you get the best in Frederick Altamont Cornwallis Twistleton, fifth Earl of good old Ickenham, you’ve got something.”

Service With a Smile, ch. 7 (1961)

“Still better,” said Mike, feeling that when you get four Bodgers, you’ve got something.

Do Butlers Burgle Banks?, ch. 14 (1968)

“She never asks anyone down who doesn’t write or paint or something.” (p. 62)

See Piccadilly Jim for other such hostesses with artistic aspirations.

registers (p. 64)

See Right Ho, Jeeves.

“There is no vice in Stanwood Cobbold. His heart is the heart of a little child.” (p. 65)

“There is no vice in Spiller,” pursued Psmith earnestly. “His heart is the heart of a little child.”

“The Lost Lambs”, ch. 4 (1908; as ch. 33 of Mike, 1909; later in Mike and Psmith)

“There is no vice in Skinner,” proceeded Jimmy. “His heart is the heart of a little child.”

Piccadilly Jim, ch. 15 (1917)

“There is no vice in J. G. Miller. His heart is the heart of a little child.”

Money in the Bank, ch. 21 (1942)

interest, elevate and amuse (p. 65)

See Leave It to Psmith.

a small boy in buttons (p. 67)

See Bill the Conqueror.

Chapter 7

two financiers with four chins (p. 70)

See Piccadilly Jim.

“You should have put your hand to your throat” (p. 70)

See The Code of the Woosters for this theatrical gesture.

how Mary must have felt (p. 70)

In the nursery rhyme “Mary had a little lamb.”

Mister Bones (p. 70)

Mike is comparing the cross-talk of their questions and answers to a minstrel act in vaudeville. See Heavy Weather.

drag home the gravy (p. 71)

As with Bertie Wooster earlier, Mike is making a humorous alteration to the stock phrase “bring home the bacon,” meaning to be successful.

Pushing the food away untasted is a universally recognized sign of love. It cannot fail to bring home the gravy.

Right Ho, Jeeves, ch. 9 (1934)

After all, I told myself, his scheme had dragged home the gravy, and in any case this was no moment for recriminations.

The Code of the Woosters, ch. 10 (1938)

his life would not be worth a moment’s purchase (p. 71)

“Clams take my correspondence course.” (p. 71)

In other words, he could teach a clam something about being silent. See The Inimitable Jeeves.

La Stoker (p. 72)

Mike uses the French feminine article, in the manner of one referring to an operatic diva, as in Sardou’s play La Tosca, source for the Puccini opera Tosca.

scenario (p. 72)

A detailed summary or outline of the plot of a play or film.

loved him not wisely but too well (p. 72)

Alluding to Othello; see Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse.

“Much more than most hippopotamuses do.” (p. 73)

Bream Mortimer was tall and thin. He had small bright eyes and a sharply curving nose. He looked much more like a parrot than most parrots do.

The Girl on the Boat/Three Men and a Maid, ch. 1 (1921/22)

He was a gallant soldier and played a hot game of polo, but he had a face like a gorilla—much more so, indeed, than most gorillas have…

Lord Havershot’s father in Laughing Gas, ch. 3 (1936)

Dolly Molloy was an attractive woman, but there were times when she could look more like a cobra about to strike than most cobras do.

Money in the Bank, ch. 12 (1942)

“Pardon me, he looks much more like a lobster than most lobsters do.”

Bill Shannon speaking of Jacob Glutz in The Old Reliable, ch. 4 (1951)

He not only looked like a dachshund, he looked considerably more like a dachshund than most dachshunds do.

Biff Christopher in Frozen Assets/Biffen’s Millions, ch. 3 (1964)

hell’s foundations are going to quiver (p. 73)

first crack out of the box (p. 73)

“Are there no limits to the powers of this wonder man?” (p. 73)

“There are practically no limits to the powers of this wonder man.”

Freddie Threepwood about Galahad Threepwood in Full Moon, ch. 5.3 (1947)

There seemed no limits to the powers of this wonder man.

Captain Jack Fosdyke in “Feet of Clay” (in Nothing Serious, 1950)

“Are there no limits to the powers of this wonder man?”

Monica Carmoyle about Jeeves in Ring for Jeeves/The Return of Jeeves, ch. 17 (1953/54)

scatter light and sweetness (p. 74)

See Piccadilly Jim.

promote the happiness of the greatest number (p. 74)

See Piccadilly Jim and Mr. Mulliner Speaking.

hep (p. 74)

See Money for Nothing.

bimbo (p. 74)

See Leave It to Psmith.

Book Two

Chapter 8

the sound of Big Ben … Park Lane (p. 76)

Not very far; anywhere from a little over a mile to a little under two miles, depending on the location along Park Lane.

corona (p. 76)

One of the best-known styles of quality cigars, the corona is straight-sided (cylindrical rather than tapered), with a rounded head and an open foot, about five and a half inches long.

in my mortal puff (p. 76)

Slang: all my life; from the association of “breath” with “life.”

as it came round for the second time (p. 76)

A neat way of describing the room-spinning effect of heavy drunkenness!

climbing into the bed as it came round for the second time

William Mulliner in “The Story of William” (1927; in Meet Mr. Mulliner, 1927/28)

he’d have been for it (p. 76)

Though the OED labels the phrase “for it” as originally British military slang meaning to be due for or liable to punishment, their first citation, from 1909, is in a public school story, meaning about to be caned. Here, of course, Corker was liable to be arrested and charged with burglary had he not escaped.

plastered (p. 77)

Another slang synonym for being drunk, first noted in the OED from the US in 1912.

peri excluded from paradise (p. 77)

See Leave It to Psmith.

The UK first edition capitalizes Peri and Paradise here.

‘Oh, what a tangled web we weave’ (p. 77)

Oh what a tangled web we weave,

When first we practise to deceive!

(1771–1832): Marmion VI:17

nipper (p. 77)

British slang, first recorded in 1859, for a young boy. Wodehouse uses it only in the speech of lower-class or East End characters.

A little freckled nipper he was when I first knew him—one of those silent kids that don’t say much and have as much obstinacy in them as if they were mules.

Henry the waiter, in “The Making of Mac’s” (1915)

“What did you want to hit the nipper for?” asked the cloth-capped man.

Big Money, ch. 6.2 (1931)

“I was taught when I was a nipper to always eat my fat.”

“Archibald and the Masses” (1935; in Young Men in Spats, 1936)

“Had a lot of practice when I was a nipper.”

Chippendale in The Girl in Blue, ch. 9.2 (1970)

flapping ears (p. 78)

Usually used figuratively for someone eager to eavesdrop or to be confided in.

Fred Thompson and one or two fellows had come in, and McGarry, the chappie behind the bar, was listening with his ears flapping.

“Scoring Off Jeeves” (1922; in The Inimitable Jeeves, ch. 5, 1923)

But, as a matter of fact, it was the work of a moment with me to chuck away my cigarette, swear a bit, leap about ten yards, dive into a bush that stood near the library window, and stand there with my ears flapping.

“Jeeves Takes Charge” (1923)

All along he had maintained that there was more in that Hall business than had become officially known, and he stood there with his ears flapping, waiting for details.

Chas. Bywater in Money for Nothing, ch. 1.1 (1928)

I regret to say, therefore, that Archibald, ignoring the fact that he belonged to a family whose code is as high as that of any in the land, instead of creeping away to his room edged at this point a step closer to the curtains and stood there with his ears flapping.

“The Reverent Wooing of Archibald” (1928; in Mr. Mulliner Speaking, 1929/30)

He could explain all, but he did not wish to do so on the first floor landing of a house where almost anybody might be listening with flapping ears.

Baxter in Summer Lightning, ch. 12.1 (1929)

“One of those gossip-writers you find at the Drones, always waiting with their ears flapping for good stuff about the eminent, would hear of it, and then we should be just as badly off as if the old boy went and picked oakum at Dartmoor or somewhere for years.”

Thank You, Jeeves, ch. 21 (1934)

No man likes to be depicted as a sort of infant Vitellius, particularly in the presence of a parlourmaid with flapping ears who is obviously drinking it all in with a view to going off and giving the cook something juicy to include in her memoirs.

“The Shadow Passes” (in Nothing Serious, 1950)

“I’m going to write her a note asking her to come and have dinner somewhere tomorrow, and the moment the coffee has been served and there isn’t a waiter hanging around with flapping ears listening to everything we say, I shall—well, I shall know what to do about it.”

French Leave, ch. 6.4 (1956)

“I recall one occasion when she ticked me off in the presence of seventeen Girl Guides, all listening with their ears flapping, and she had never spoken more fluently.”

Bertie speaking of Lady Florence Craye in Much Obliged, Jeeves, ch. 13 (1971)

But sometimes used in a physical sense:

His hair was disordered, and his masterful nose was trapped by a pair of steel-rimmed pince-nez cunningly attached to his flapping ears with ginger-beer wire.

“Ukridge’s Dog College” (1923; in Ukridge, 1924)

Ukridge adjusted the ginger-beer wire that held his pince-nez to his flapping ears, and looked wounded.

“The Level Business Head” (1926; in Lord Emsworth and Others, 1937)

“You keep saying to yourself: ‘Think of that pimple on Smith’s nose’ . . . ‘Consider Jones’s flapping ears’ . . . ”

The Code of the Woosters, ch. 3 (1938)

Damsels in distress had merely to press a button, and we would race up with our ears flapping, eager to do their behest.

Uncle Dynamite, ch. 11 (1948)

“You know that novelist of mine with the flapping ears and the spots on his coat?”

“The Girl in the Pink Bathing Suit” (in America, I Like You, 1956)

black frosts … garden of dreams (p. 78)

[Eve] was a kind-hearted girl, and it irked her to have to be continually acting as a black frost in Freddie’s garden of dreams.

Leave It to Psmith, ch. 10.2 (1923)

Freddie, when at Blandings, had a way of mooning about looking like a bored and despairing sheep, with glassy eyes staring out over an eleven-inch cigarette holder, which had always been enough to bring a black frost into this Eden of his.

Full Moon, ch. 1 (1947)

“I keep proposing to her, and she steadfastly continues to be a black frost in my garden of dreams.”

The Old Reliable, ch. 3 (1951)

Still, it was not for her to act as a black frost in Barmy’s garden of dreams.

Barmy in Wonderland, ch. 12 (1952)

And the greasy bird’s first words sent a black frost buzzing through his garden of dreams.

“Oofy, Freddie and the Beef Trust” (in A Few Quick Ones, 1959)

A look of regret and pity had come into Lord Ickenham’s face. It pained him to be compelled to act as a black frost in this young man’s garden of dreams, but he had no alternative.

Service With a Smile, ch. 9 (1961)

Gally shook his head. It pained him to be compelled to act as a black frost in his young friend’s garden of dreams, but facts had to be faced.

Galahad at Blandings, ch. 4.4 (1965)

put the tips of his fingers together (p. 79)

Wodehouse regards this as an appropriate pose for various professionals when giving advice, including detectives (perhaps because Sherlock Holmes is described as doing it in five of the twelve stories in the Adventures), lawyers, doctors, and other specialists.

Oakes sank into a chair like a crouching leopard, and placed the tips of his fingers together.

“The Education of Detective Oakes” (1914)

His father, taking a chair, placed the tips of his fingers together and in this attitude remained motionless, a figure of disapproval and suppressed annoyance.

Something Fresh/Something New, ch. 2.1 (1915)

Mr. Sturgis leaned back, and placed the tips of his fingers together.

Piccadilly Jim, ch. 17 (1917)

He settled himself comfortably in his chair, and placed the tips of his fingers together.

The Oldest Member in “The Awakening of Rollo Podmarsh” (1923; in The Heart of a Goof, 1926)

“Stammering,” proceeded the specialist, putting the tips of his fingers together and eyeing George benevolently, “is mainly mental and is caused by shyness, which is caused by the inferiority complex, which in its turn is caused by suppressed desires or introverted inhibitions or something.”

“The Truth about George” (1926; in Meet Mr. Mulliner, 1927/28)

He settled himself in a deep arm-chair, and putting the tips of his fingers together after a little preliminary difficulty in making them meet, leaned back, all readiness to listen to whatever trouble it was that was disturbing this new friend of his.

Percy Pilbeam in Summer Lightning, ch. 13.3 (1929)

Mr. Wetherby put the tips of his fingers together.

If I Were You, ch. 22 (1931)

He examined Adrian carefully, then sat back in his chair, with the tips of his fingers touching.

“The Smile That Wins” (1931; in Mulliner Nights, 1933)

[Percy Pilbeam] had the tips of his fingers together, Monty noted approvingly.

Heavy Weather, ch. 8 (1933)

Rupert Baxter was sitting back in his chair, tapping the tips of his fingers together.

Uncle Fred in the Springtime, ch. 11 (1939)

“What, another? All right, show her in,” said Joss, leaning back and putting the tips of his fingers together.

Quick Service, ch. 2 (1940)

“Well, Brussels, then. Where the sprouts come from. Brussels is just as good. Proceed,” said Barmy, putting the tips of his fingers together.

Barmy in Wonderland, ch. 18 (1952)

Until this passage left the aged relative’s lips Kipper had been sitting with the tips of his fingers together, nodding from time to time as much as to say “Caustic, yes, but perfectly legitimate criticism,” but on hearing this excerpt he did another of his sitting high jumps, lowering all previous records by several inches.

Jeeves in the Offing, ch. 13 (1960)

Chimp leaned back and put the tips of his fingers together.

The Ice in the Bedroom, ch. 17 (1961)

Jerry put the tips of his fingers together.

Biffen’s Millions/Frozen Assets, ch. 8.2 (1964)

packet of gaspers (p. 79)

Cigarettes, especially inexpensive or harsh ones.

half a dollar (p. 79)

Slang for half a crown; see Summer Lightning.

the risk you’re running of everlasting fire (p. 79)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

spoiling the ship for a ha’p’orth of tar (p. 79)

See Right Ho, Jeeves.

sitting up and taking nourishment (p. 79)

A stock medical phrase for a stage of recovery from illness or injury. This is the only time so far found in Wodehouse that the phrase is used in relation to smoking.

When the bell rang for the interval that morning, Mike was, as it were, sitting up and taking nourishment.

Jackson, Junior, ch. 21 (1907; in Mike, 1909)

“Sitting up, you will notice,” he added, waving a hand in the direction of his teacup, “and taking nourishment.”

The Gem Collector, ch. 6 (1909)

“I rejoice to say that my high-born master is better. He has regained consciousness, and is sitting up and taking nourishment.”

“Brother Alfred” (1913)

I’m bound to own that, by the time I got her letter, the wound had pretty well healed, and I was to a certain extent sitting up and taking nourishment.

“Doing Clarence a Bit of Good” (1913; in My Man Jeeves, 1919)

“Aubrey,” she said … “is very much knocked about, but he is conscious and sitting up and taking nourishment.”

“The Episode of the Live Weekly” (1914)

…the stricken cow had taken a sudden turn for the better, and at last advices was sitting up and taking nourishment with something of the old appetite.

“Lord Emsworth Acts for the Best” (1926; in Blandings Castle and Elsewhere, 1935)

a dial like yours (p. 80)

The OED has citations for the slang use of dial to mean the human face beginning in 1837.

stick on dog (p. 80)

A variant of put on dog: to show off, to be pretentious. Wodehouse used it once about himself:

Dash it, I mean to say, I don’t want to stick on dog and throw bouquets at myself, but if I were not pretty good, would Matthew Arnold have written that sonnet he wrote about me, which begins:

Others abide our question. Thou art free.

Over Seventy, ch. 5.2 (1957)

like Jeshurun who waxed fat and kicked (p. 81)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

The Wages of Sin you might call it. (p. 81)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

look slippy (p. 81)

See Full Moon.

flotsam and jetsam (p. 81)

See Laughing Gas.

Chapter 9

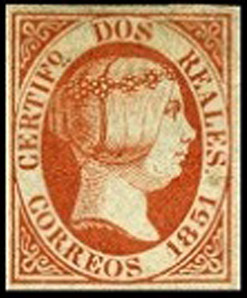

Spanish 1851 dos reales blue unused (p. 82)

According to this website, the 1851 dos reales stamp should be red, not blue.

According to this website, the 1851 dos reales stamp should be red, not blue.

Servants Hall (p. 83)

Thus in the US first edition, though the UK first has the far more common possessive Servants’ Hall here.

One-Man Brains Trust (p. 85)

During the latter part of the nineteenth century, trust came to denote a consolidation of companies to dominate an industry, an effort to create a monopoly. Figurative use of “brain trust” to mean a team or collection of intellectuals or experts began even before the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 was enacted. The term soon became associated with a group of expert advisers to a politician or candidate, and was made most famous when the New York Times used “Brains Trust” for a team of advisers to presidential candidate Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1932.

‘Mitt Mr. Cobbold’ (p. 85)

See Money for Nothing.

“Exactly. And I hold her hand as in a vise.” (p. 85)

The UK first edition reads differently here:

“Much friendlier. And what happens then, you ask. I will tell you. I hold her hand as in a vice.”

‘My hero!’ (p. 86)

See The Mating Season.

ha’penny nap (p. 86)

A simple card game of the bridge/whist/euchre family in which players are dealt hands of five cards and bid on how many tricks they expect to take, the winning bidder selecting the trump suit. Each trick bid and won (but not overtricks) earns a halfpenny from each other player.

a little more on the piano side (p. 89)

The UK first edition italicizes piano, which is proper, since this is an Italian word used in music to indicate that a passage should be played or sung softly.

“It’s a ramp!” (p. 89)

See Cocktail Time.

try-on (p. 89)

The OED calls this a slang term for an attempt, particularly a deceitful one, and has citations in this sense from 1874 onward.

unseeing eyes (p. 90)

Chapter 10

a more cheerio butler (p. 92)

bien-être (p. 92)

French for “well-being”; a state of comfort.

eyes seemed to be suspended on stalks (p. 92)

See Thank You, Jeeves.

alabaster (p. 92)

See Meet Mr. Mulliner.

cushat dove (p. 93)

See Cocktail Time.

first fine careless rapture (p. 93)

See Something Fresh.

The typewriter falters as it records his words (p. 93)

Many of Wodehouse’s characters use typewriters, as he himself did; in fact, in Psmith, Journalist he noted that “nobody uses pens in New York” (ch. 4), and his autobiographical books and articles often mention his typewriters. But this is the only instance in his fiction so far found that alludes to the author’s typewriter, here used as a metaphor for the narrator finding it difficult to write something.

pots of money (p. 94)

See Ukridge.

George S. Kaufman … Robert E. Sherwood (p. 95)

Both were tall, slender Pulitzer-Prize-winning playwrights in America. Sherwood (1896–1955) stood 6′8″ tall (2.03 m). Kaufman (1889–1961) was well over six feet tall.

The UK edition substitutes two British playwrights here, Terence Rattigan (1911–1977) and Ian Hay (pen name of John Hay Beith, 1876–1952, who collaborated with Wodehouse on several plays).

struck a new note (p. 95)

Wodehouse treated this phrase as a cliché of literary and dramatic criticism.

Ralston McTodd, the powerful young singer of Saskatoon (‘Plumbs the depths of human emotion and strikes a new note’—Montreal Star)

Leave It to Psmith, ch. 6.4 (1923)

He looked down and there was his pet author, William Edgar (“Strikes a New Note”) Delamere.

“The Hollywood Scandal” in Louder and Funnier (1932)

It was evident that Gussie was striking something of a new note in Market Snodsbury scholastic circles.

Right Ho, Jeeves, ch. 17 (1934)

“But she’s given me her latest to read while I’m here, and I can see from the first page that it’s the bezuzus. Strikes a new note, as you might say.”

Uncle Dynamite, ch. 9.4 (1948)

cinnamon bear (p. 95)

See A Damsel in Distress.

at liberty (p. 95)

Theatrical jargon for “unemployed”; the OED has citations in this sense from 1879 onward.

nerveless fingers (p. 96)

Often used by Wodehouse in describing a state of surprise or alarm which causes someone to drop something.

I now came down to earth with a bang: and my slice of cake, slipping from my nerveless fingers, fell to the ground and was wolfed by Aunt Agatha’s spaniel, Robert.

“Jeeves and the Impending Doom” (1926; in Very Good, Jeeves, 1930)

At the moment she had been speaking with a good deal of enthusiasm of Ronald Colman; but at the sight of George Murgatroyd the words died on her lips, a strange light came into her eyes, and a bag of pear-drops fell from her nerveless fingers.

“Prospects for Wambledon” (1929; in Louder and Funnier, 1932)

The bottle fell from his nerveless fingers and rolled across the floor, spilling its contents in an amber river, but he was too heavy in spirit to notice it.

“The Story of Webster” (1932; in Mulliner Nights, 1933)

He had been stirring his coffee when he made the discovery, and the spoon fell from his nerveless fingers.

“Bingo and the Peke Crisis” (1937; in Eggs, Beans and Crumpets, 1940)

“If I could show you that list Boko drafted out of the things he wants me to say—I unfortunately left it in my room, where it fell from my nerveless fingers—your knotted and combined locks would part all right, believe me.”

Joy in the Morning, ch. 20 (1946)

The slim volume fell from my nerveless fingers, and I goggled at him.

The Mating Season, ch. 9 (1949)

He leaped like a jumping bean and the cigarette fell from his nerveless fingers.

Conky Biddle in “How’s That, Umpire?” (in Nothing Serious, 1950)

She picked up the cake with jam in the middle which had fallen from her nerveless fingers and ate it in a sort of trance.

Lady Constance Keeble in Pigs Have Wings, ch. 3.1 (1952)

Lavender Briggs’ jaw had fallen. So, slipping from between her nerveless fingers, had her bag.

Service With a Smile, ch. 9.2 (1961)

the Pippa Passes outlook (p. 96)

See Leave It to Psmith.

of all sad words of tongue or pen (p. 97)

See Leave It to Psmith.

Chapter 11

Prisoner of Chillon (p. 97)

The Prisoner of Chillon is an 1816 narrative poem by Lord Byron, about the monk François Bonivard, imprisoned in the Château de Chillon from 1532 to 1536. The only other reference so far found in Wodehouse:

An importer and exporter whose heart is in his work feels like the Prisoner of Chillon when he is kept at home with a cold in the head.

Pearls, Girls and Monty Bodkin, ch. 11 (1972)

abomination of desolation (p. 97–98)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

the upholsterer of the Spanish Inquisition (p. 98)

Men have a knack of making themselves comfortable which few women can ever achieve. My Aunt Julia’s idea of a chair, for instance, was something antique made to the order of the Spanish Inquisition.

“Ukridge and the Old Stepper” (1928; in Eggs, Beans and Crumpets, 1936)

the Serpent in his lordship’s Garden of Eden (p. 98)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

G.H.Q. (p. 98)

See Heavy Weather.

things were looking up (p. 99)

The usage of the phrase “looking up” for an increase in value originated in nineteenth-century financial circles, as for stock prices, and then generalized to any favorable expectation. See also Bill the Conqueror for an earlier usage and for the Gershwin song with a similar title.

two minds with but a single thought (p. 100)

See Right Ho, Jeeves.

to find some formula … a round table (p. 100)

Journalistic jargon for diplomatic conferences.

brought the good news to [Ghent] from Aix (p. 102)

See Ice in the Bedroom.

now you’re tooting (p. 102)

US slang for “you’re absolutely right”; the only instance so far found in Wodehouse.

talk turkey (p. 102)

See Right Ho, Jeeves.

from soup to nuts (p. 102)

See Blandings Castle and Elsewhere.

Into each life some rain must fall (p. 103)

See Ice in the Bedroom.

The appetite grows by what it feeds on (p. 103)

From Hamlet: see Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse.

cooler (p. 103)

An American slang word for prison, dating from the late nineteenth century.

East Dulwich (p. 104)

See Very Good, Jeeves.

make the check open (p. 104)

See Heavy Weather.

a tigress hearing the cry of her cub (p. 104)

There are many allusions to tigresses in Wodehouse; these are the ones that also mention her young. See references to the look in their eyes at p. 213 below, tigresses that sleep within at Something Fishy, and many miscellaneous ones at Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit.

I had been wondering when my new plus-fours would come under discussion, and I was prepared to battle for them like a tigress for her young.

“Jeeves and the Kid Clementina” (1930; in Very Good, Jeeves, 1930)

No sudden roar, as of a tigress defending her cubs, came to break the stillness.

Hot Water, ch. 11.2 (1932)

“Let us now suppose that you sloshed that tiger cub, and let us suppose further that word reached its mother that it was being put upon. What would you expect the attitude of that mother to be? In what frame of mind do you consider that that tigress would approach you?”

Right Ho, Jeeves, ch. 13 (1934)

“Chuffy has often told me that her attitude towards Seabury resembles that of a tigress towards its cub.”

Thank You, Jeeves, ch. 6 (1934)

She thought of poor old Buck, and how worried he was, and the picture that rose before her eyes of him frowning and chewing his pipe as he paced the terrace made her resemble a very easygoing tigress whose cub has been attacked.

Summer Moonshine, ch. 14 (1937)

“What Jeeves is saying is that a word from you to the effect that you have seen it in my room will bring him bounding up here like a tigress after its lost cub, thus leaving you a clear field in which to operate.”

The Code of the Woosters, ch. 11 (1938)

“My position, as I see it, is roughly that of one who has removed a favourite cub from the custody of a rather more than usually short-tempered tigress, and is obliged to carry it on his person in the animal’s immediate neighbourhood.”

Joy in the Morning, ch. 25 (1946)

“Tell me, Bertie, have you ever stolen a cub from a tigress?”

The Mating Season, ch. 13 (1949)

“It was like being apprehended by a tigress while in the act of abstracting one of its cubs, madam.”

The Old Reliable, ch. 5 (1951)

Chapter 12

changeling (p. 106)

Someone substituted for another person, especially by magical means as in a fairy story.

run the gamut of the emotions (p. 107)

Originally “gamut” had musical meanings, particularly the range of musical notes that a single voice or instrument can produce. So, figuratively, running the gamut here means experiencing the whole scale, the widest possible variety of feelings.

Damocles (p. 107)

Butlers, he knew, though crushed to earth, will rise again (p. 107)

See A Damsel in Distress.

grapple him to her soul with hoops of steel (p. 107)

From Hamlet: see Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse.

the word in season (p. 107)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

“Pater” (p. 108)

Latin for “father”; see A Damsel in Distress.

roupy (p. 108)

Hoarse or husky of voice. Related to the poultry disease “roup” (see Love Among the Chickens).

quivered like a blancmange (p. 108)

A quivery molded cold dessert, made of flavored and sweetened milk stiffened with starch or gelatin.

“Himself. Not a picture.” (p. 109)

See Blandings Castle and Elsewhere.

with her foot in her hand (p. 110)

An obscure turn of phrase, not covered in the OED or found so far in slang dictionaries; from context the apparent meaning is “as fast as possible.” The OED does list a similar phrase, “to take one’s foot in one’s hand” meaning to depart or set out on a journey, but this doesn’t seem to be the sense here. Wodehouse’s usages are confined to a few years following World War Two.

It only needed a word from Dame Daphne Winkworth to Aunt Agatha … to bring the old relative racing down to Deverill Hall with her foot in her hand.

The Mating Season, ch. 10 (1949)

“No doubt he will be round here with his foot in his hand within ten minutes of getting the glad news.”

“The Shadow Passes” (in Nothing Serious, 1950)

basketful of puppies (p. 110)

Squeakings broke out once more at the other end of the wire.

“Stop it!” said Packy.

“Stop what?”

“Stop going on like a basketful of puppies.”

Hot Water, ch. 2.6 (1932)

a bob a nob (p. 110)

One shilling per person.

“Add gate crashers, and I can’t budget for less than four hundred. At a bob a nob.”

“The Masked Troubadour” (1936; in Lord Emsworth and Others, 1937)

“Call it on an average night two hundred dinners at ten bob a nob, that’s a hundred quid right out of the box.”

Full Moon, ch. 10.6 (1947)

the dust beneath our chariot wheels (p. 111)

See Summer Moonshine.

‘The Voice That Breathed o’er Eden’ (p. 112)

See Laughing Gas.

tripping over a rug (p. 113)

Stanwood joins the group of Wodehouse’s beefy young men who are clumsy indoors.

The manner in which he now tripped over a rug and cannoned into an occasional table, upsetting it with all the old thoroughness, showed me that at heart he still remained the same galumphing man with two left feet, who had always been constitutionally incapable of walking through the great Gobi desert without knocking something over.

Harold “Stinker” Pinker, in The Code of the Woosters, ch. 8 (1938)

…there came from without the sound of some heavy body tripping over a rug, and Bill [Lister] came in.

Full Moon, ch. 8.1 (1947)

Chapter 13

bouleversé (p. 113)

Upset, distraught; “bowled over”

to swallow his uvula (p. 114)

A fleshy appendage at the back of the roof of the mouth, hanging from the center of the margin of the soft palate. It cannot be swallowed; in fact, during swallowing it helps prevent food and liquid from going up into the back of the nasal cavity.

His tongue tied itself in a bow-knot round his uvula, and he could say no more.

“The Rough Stuff” (1921; in The Clicking of Cuthbert, 1922)

Suppose somebody laid hands on you and put you in a large round tub. Suppose he then proceeded to send the tub spinning down an incline so arranged that at intervals of a few feet it spun round and bumped violently into something, causing your heart to get all scrambled up with your uvula and your brain-cells to come unstuck.

“A Word about Amusement Parks” (in Louder and Funnier, 1932)

I tried to utter, but could not. The tongue had got all tangled up with the uvula, and the brain seemed paralyzed.

Joy in the Morning, ch. 18 (1946)

He beamed on the girl, and having released his tongue, which had got entangled with his uvula, spoke in a genial and welcoming voice.

Uncle Dynamite, ch. 8 (1948)

It is true that all I said was “Jeeves!” but that wasn’t such bad going for one whose tongue had so recently been tangled up with the uvula, besides cleaving to the roof of the mouth.

The Mating Season, ch. 8 (1949)

“You can take it from me, Jerry o’ man, that if a fellow raised from rags to riches at the breakfast table isn’t tanked to the uvula by nightfall, it simply means he hasn’t been trying.”

Frozen Assets/Biffen’s Millions, ch. 4.3 (1964)

At last managing to free my tongue from the uvula with which it had become entangled, I found speech, as I dare say those Darien fellows did eventually.

Aunts Aren’t Gentlemen, ch. 10 (1974)

hep (p. 114)

See Money for Nothing.

not to be comforted (p. 114)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

banner with the strange device (p. 115)

Usually followed by “Excelsior!” See Cocktail Time.

‘Anything goes.’ (p. 115)

Title of a 1934 musical comedy, with a book originally written by Guy Bolton and Wodehouse, revised by Howard Lindsay and Russel Crouse, with music and lyrics by Cole Porter. Wodehouse also adapted some of the American topical references in the song lyrics for the London production in 1935.

smirching the old escutcheon (p. 115)

See Heavy Weather.

Caesar Romero (p. 116)

Printed as Cæsar Romero in the UK first edition. But the American actor Cesar Romero (1907–1994) used the simpler Spanish spelling of his first name, sometimes accented as César.

tie a can to your spiritual struggles (p. 116)

See Sam the Sudden.

escritoire (p. 117)

Writing desk; a French word adopted into English since the eighteenth century.

Black Onion gang (p. 119)

Apparently a Wodehouse coinage.

three-pipe problems (p. 119)

“What are you going to do, then?” I asked.

“To smoke,” he answered. “It is quite a three pipe problem, and I beg that you won’t speak to me for fifty minutes.”

Arthur Conan Doyle: “The Red-Headed League” (1891)

Chapter 14

tête-à-tête (p. 120)

French: literally head-to-head; figuratively face to face, as a conversation. The UK first edition prints this in italics as a foreign phrase.

representatives of Notre Dame and Minnesota (p. 120)

Football teams from these two universities. The UK first edition hyphenates Notre-Dame here.

his soul had passed through the furnace (p. 120)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

nose glasses (p. 120)

More often referred to in Wodehouse as pince-nez: eyeglasses with a springy frame, held to the face by the pressure of pads on either side of the nose instead of having temples hooking over the ears.

sissies (p. 120)

This derogatory term for boys or men whose interests or behavior are considered effeminate or unmanly dates from the late nineteenth century in the US, and Wodehouse uses it mostly in the speech of American characters like Stanwood here.

“An’ cut out dat blamed sissy way of talking, you rummy,” bellowed Buck, with a sudden lapse into ferocity.

The Little Nugget, ch. 14 (1913)

“Ambassadors have to wear uniforms and knickerbockers . . . the sissies.”

Mr. Gedge in Hot Water, ch. 1.5 (1932)

“And a gardenia, she says. And spats. I shall feel like a sissy.”

Mr. Brinkmeyer/Brinkwater in Laughing Gas, ch. 12 (1936)

it was a pipe (p. 121)

Once again, Wodehouse places Stanwood as an American by putting American slang into his speech. Green’s Dictionary of Slang has citations from 1896 to 1982 for the use of “pipe” to mean something that is a certainty or is easily accomplished (his sense number 4); he notes that it is an abbreviation for the older “lead-pipe cinch.”

“This show’s a pipe, and any bird that comes in is going to make plenty.”

Barmy in Wonderland, ch. 8 (1952)

bozo (p. 121)

More American slang; see Bill the Conqueror.

Her Nibs (p. 121)

Slang title for a female aristocrat.

smackers (p. 121)

A slang term used both for dollars and for pounds in Wodehouse; see Bill the Conqueror.

eaten your salt (p. 121)

Been a guest at a meal at which you were the host.

the iron twisting about in his soul (p. 121)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

fiend in human shape (p. 122)

See The Mating Season.

United States Marines (p. 122)