Full Moon

by

P. G. Wodehouse

Literary and Cultural References

This is part of an ongoing effort by the members of the Blandings Yahoo! Group to document references, allusions, quotations, etc in the works of P. G. Wodehouse. These notes are by Neil Midkiff, with contributions from others as credited below.

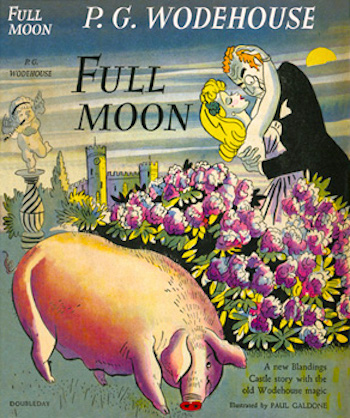

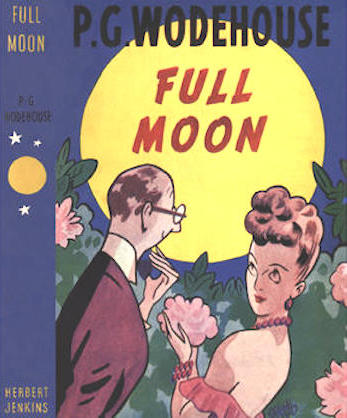

The book was published by Doubleday in the USA on 22 May 1947 (left), and by Herbert Jenkins

in the UK on 17 October 1947 (right). A heavily condensed “complete-in-one-issue” version appeared in the US Liberty magazine for November, 1947; this abridgement has not been examined in detail.

The book was published by Doubleday in the USA on 22 May 1947 (left), and by Herbert Jenkins

in the UK on 17 October 1947 (right). A heavily condensed “complete-in-one-issue” version appeared in the US Liberty magazine for November, 1947; this abridgement has not been examined in detail.

Page references in these notes are based on the 1947 USA first edition.

|

Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 Chapter 6 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 9 Chapter 10 |

Chapter One

Runs from p. 1 to p. 20 in the 1947 Doubleday edition.

Blandings Castle and district (p. 1)

We first visit Blandings Castle in Something Fresh/Something New (1915). The castle is in Shropshire, a historic county in the West Midlands of England, adjacent to Wales.

refined moon … nearly at its full (p. 1)

We learn in Chapter Four that it is “a lovely summer night”; in midsummer the sun is well north of the celestial equator, and the full moon, opposite the sun, is south of the equator, so at the latitude of Shropshire (approximately 52½ degrees North) the midsummer full moon will traverse a low arc, rising from the southeast horizon through a low elevation in the south (sometimes even lower than 10 degrees of altitude) to the southwest horizon.

At this low angle, the moon’s light will be yellowed and dimmed by Earth’s atmosphere, giving a “refined” and romantically shadowed glow, rather than the more brilliant light of a winter full moon at a much higher altitude.Clarence, ninth Earl of Emsworth (p. 1)

Also first met in Something Fresh/Something New (1915), and a key figure in all the later novels and stories in the Blandings Castle saga. Described as a long, lean, baldheaded, stringy man of about sixty; a widower for many years, with ten sisters, two sons (George, Viscount Bosham, and the Hon. Freddie Threepwood), and at least one daughter (Lady Mildred Mant).

Lady Hermione Wedge (p. 1)

This is the first mention of Lady Hermione, one of Lord Emsworth’s ten sisters. She reappears as chatelaine at Blandings in The Brinksmanship of Galahad Threepwood (1964)/Galahad at Blandings (1965), but by A Pelican at Blandings (1969)/No Nudes is Good Nudes (1970), is no longer at Blandings nor on speaking terms with her brother Clarence.

Veronica Wedge (p. 1)

This is her first appearance in the saga. Somewhat confusingly, her marriage to Tipton Plimsoll takes place in “Birth of a Salesman” (1950), but in The Brinksmanship of Galahad Threepwood (1964)/Galahad at Blandings (1965) she is still engaged to him, so that book’s events must take place earlier than the 1950 short story.

Colonel Egbert Wedge (p. 1)

First met here; also in The Brinksmanship of Galahad Threepwood (1964)/Galahad at Blandings (1965).

bijou (p. 2)

The French word bijou means a jewel, or something small and pretty.

Empress of Blandings (p. 2)

Lord Emsworth’s pride and joy, a black Berkshire sow, already twice a prizewinner in the Fat Pigs class at the Shropshire Agricultural Show. Introduced in “Pig-hoo-o-o-o-ey!” (1927) as the winner at the eighty-seventh annual show; her second win is foreshadowed at the end of Heavy Weather (1933). Her third win, in successive years, is awarded at the end of Pigs Have Wings (1952); this is among the evidence that teaches us to disregard the year of publication as a clue to the internal timing of the events in the sequence of Wodehouse stories.

wigwam (p. 2)

This word is not to be taken literally as meaning an architectural echo of Native American dwellings, but rather used for humorous effect, as Bertie Wooster does in applying it to Lord Bittlesham’s London home in “Bingo and the Little Woman” (1922; in The Inimitable Jeeves, 1923). See also the notes to The Inimitable Jeeves for an earlier jocular literary usage from Sir Walter Scott, of all people.

Queen’s Hall (p. 2)

A concert venue in Langham Place, London, built in 1893 but destroyed by German bombing in 1941. It was the home of the BBC Symphony and the London Philharmonic Orchestra, and could accommodate about 2,500 listeners.

Sir Henry Wood (p. 2)

Sir Henry Joseph Wood (1869–1944), one of England’s best-known conductors of classical music and opera, who led the annual series of promenade concerts (familiarly known as “The Proms” to this day) for nearly half a century until his death. When the Queen’s Hall was destroyed in the war, the Proms moved to the Royal Albert Hall, where they remain today.

lumbago (p. 4)

Pain in the muscles of the lower back, often thought to be brought on by chilly damp conditions. Frequently mentioned by Wodehouse characters; Mr. Pett denies having it in Piccadilly Jim; Jill Mariner has sympathy for waiters with it in The Little Warrior; Colonel Bodger has it in “The Awakening of Rollo Podmarsh”; Murgatroyd suffers from it in “A Slice of Life”; Dudley Pickering’s Subconscious Self warns himself of the possibility in Uneasy Money; among many others.

Freddie (p. 4)

The Honorable Frederick Threepwood, Lord Emsworth’s younger son, whom he had considered a wastrel, but who seems to have reformed because of his marriage to the daughter of an American dog-biscuit tycoon; see “The Custody of the Pumpkin” (1924).

Dora (p. 4)

Lady Dora Garland, another of Lord Emsworth’s sisters; a widow, living in Grosvenor Square, London, with her daughter Prudence. Her late husband Sir Everard Garland, K.C.B., died before the events of this story, which is her first appearance (even though “offstage” in this book). She returns in Pigs Have Wings (1952) and The Brinksmanship of Galahad Threepwood (1964)/Galahad at Blandings (1965), and is mentioned in A Pelican at Blandings (1969)/No Nudes is Good Nudes (1970) as never leaving London except to go to fashionable resorts on the Riviera and in Spain.

Constance (p. 4)

Lady Constance Keeble, the sister of Lord Emsworth who we see most often as the chatelaine of Blandings, from Leave It to Psmith (1923) through Uncle Fred in the Springtime (1939) and from Pigs Have Wings (1952) to Service With a Smile (1961). In The Brinksmanship of Galahad Threepwood (1964)/Galahad at Blandings (1965) she has married her longtime friend James Schoonmaker of New York, after which she is sometimes but not always at Blandings.

Julie (p. 4)

Colonel Wedge may be the only man who addresses his sister-in-law Lady Julia Fish as “Julie”; this dominating woman, mother of Ronnie Fish, is mentioned in Money for Nothing (1928) and takes a major role in Summer Lightning/Fish Preferred (1929) and Heavy Weather (1933).

deep waters (p. 5)

See Leave It to Psmith.

lobelias (p. 5)

See Leave It to Psmith.

tête-à-tête (p. 6)

See Hot Water.

cross-talk team (p. 6)

A vaudeville or music-hall comedy act for two players, with rapid-fire questions and answers and often physical comedy as well, sometimes involving ethnic humor and stereotypes. Barmy Fotheringay-Phipps and Pongo Twistleton make up such a team for a Drones Club entertainment in “Tried in the Furnace” (1935).

married the daughter (p. 6)

See “The Custody of the Pumpkin” (1924).

eleven-inch cigarette holder (p. 7)

Freddie is being indirectly described as a dandy of sorts here; according to Wikipedia, the usual man’s cigarette holder was no more than four inches long. A 1925 article quotes Wodehouse on the various distinctions of the silly asses and drones in his stories:

The Crumpet’s cigarette-holder is seldom more than 8in. long, while that of the Pieface at least 13.

Ronnie Fish uses an eleven-inch one in Money for Nothing, ch. 5.4 (1928) and a long one in Summer Lightning, ch. 2.1 (1929); Lord Topham uses an eleven-inch one in The Old Reliable, ch. 18 (1951). Aunt Dahlia accuses Bertie of using a twelve-inch one in Right Ho, Jeeves, ch. 4 (1934).

this Eden of his (p. 7)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

as though of hemlock he had drunk (p. 7)

Alluding to Ode to a Nightingale by John Keats:

My heart aches, and a drowsy numbness pains

My sense, as though of hemlock I had drunk,

Or emptied some dull opiate to the drains

One minute past, and Lethe-wards had sunk:

Ben Bolt’s Alice (p. 8)

From the poem “Ben Bolt” by Thomas Dunn English:

Don’t you remember sweet Alice, Ben Bolt,—

Sweet Alice whose hair was so brown,

Who wept with delight when you gave her a smile,

And trembled with fear at your frown?

racecourse tout (p. 10)

One who offers to sell information (real or suppositious) on the performance of racehorses and their chances of winning.

The UK edition hyphenates “race-course” here; both editions hyphenate it in Chapter Nine.

three-card-trick (p. 10)

Defined in the OED as “a trick popular with race-course sharpers, also known as find the lady, in which a queen and two other cards are spread out face downwards, and bystanders invited to bet which is the queen.”

beau sabreur (p. 10)

French, literally “handsome swordsman”; a nickname for Joachim Murat (1767–1815), brother-in-law of Napoleon. In general use, a handsome or dashing adventurer.

called spades spades (p. 11)

Others in Wodehouse who use this term for plain speaking:

It involved some rather warmish medieval dialogue, I recall, racy of the days when they called a spade a spade, and by the time the whistle blew, I’ll bet no Daughter of the Clergy was half as distressed as I was.

Bertie Wooster, in Right Ho, Jeeves, ch. 10 (1934)

Monty winced. He was familiar with his companion’s reputation in Hollywood as a man who called a spade a spade, and had he merely done that now, he would have had nothing to complain of. He had no objection to Mr. Llewellyn describing spades as spades, but he keenly resented his reference to Gertrude Butterwick as a beefy girl with large feet.

Pearls, Girls and Monty Bodkin/The Plot That Thickened, ch. 5.2 (1969/70)

Dangerous Dan McGrew (p. 12)

See Leave It to Psmith.

submerged (p. 12)

A euphemism for being drunk, infrequent in Wodehouse; the word more commonly appears in the sociological phrase “submerged tenth” for the poorest of the poor. But the meaning is clear here, and is explicated by Reggie Byng in A Damsel in Distress, ch. 20 (1919), in which he equates being pickled to the eyebrows, getting a trifle submerged, filling the radiator, and shoving himself more or less below the surface.

Jos. Waterbury was there, wearing the unmistakable air of a man who has been more or less submerged in unsweetened gin for several hours…

“The Masked Troubadour” (in Lord Emsworth and Others, 1937)

selling platers (p. 15)

See Laughing Gas.

collateral branches … Debrett’s Peerage (p. 15)

Branches of a titled family not in the direct line of descent: cousins, nephews, etc. of the titleholders. For Debrett see Lord Emsworth and Others.

Quaglino’s (p. 16)

An upscale restaurant at 16 Bury Street, London, opened in 1929 by Giovanni and Ernesto Quagliano, and patronized by royalty and celebrities; it was sold to hotel operators in the 1960s and its reputation faded until it closed in 1977. A successor restaurant on the same site opened in 1993, with the aim of reviving the spirit of the original.

every dashed thing under the sun (p. 16)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

the real ginger (p. 18)

Slang for something spicy or hot, here referring to an expression with a strong meaning.

in sickness and in health (p. 18)

Since this phrase is more often associated with the traditional church service of holy matrimony, it seems that Wodehouse may have used it to emphasize the depth of Lord Emsworth’s bond with his prize pig.

Chapter Two

Runs from p. 21 to p. 37 in the 1947 Doubleday edition.

Greenwich Observatory (p. 21)

That is, the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, London, established in 1675 by King Charles II, who created the office of Astronomer Royal, first held by John Flamsteed. It long served as the “home” of international time standards, since Greenwich Mean Time was computed from there (now superseded by Coordinated Universal Time), and the Prime Meridian of longitude passes through it. Now mostly a museum, it is still a fascinating place to visit, and one can stand there with one foot in the Western Hemisphere and one in the Eastern Hemisphere.

K.C.B. (p. 21)

Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath — the middle class of the fourth-most-senior of the British Orders of Chivalry. King George I founded the Order in 1725; it was restructured in 1815 and divided into Military and Civil Divisions in 1847. Senior military officers and senior civil servants make up most of the members of the Order; at present there can be no more than 355 Knights Commander and Dames Commander of the Order of the Bath. Military KCBs must at least hold the rank of vice admiral, major general, or air vice marshal; so we know that the late Sir Everard held a high rank.

“not much of her, but what there was was good” (p. 22)

Wodehouse had used a similar phrase earlier:

There was not much of her, but what there was was charming.

“The Dastardly Behaviour of Bashmead” (1903).

And later:

Jill stiffened haughtily. There was not much of her, but what there was she drew to its full height.

Ring for Jeeves/The Return of Jeeves, ch. 19 (1953/54)

half-portion (p. 22)

A small person; the OED quotes Damon Runyon as its first citation, from 1911, and its last citation, from 1967, is from Wodehouse, in Company for Henry. But Wodehouse had used it as early as 1912:

“It’s Tom I’m worrying myself to a half portion about.”

The Prince and Betty (1912 magazine version)

She might not be able to get Sir Lancelot or Sir Galahad; but she was not going to be satisfied with a half-portion.

Other Wodehouse characters so described include Sally Nicholas in The Adventures of Sally (1921/22); Julia Ukridge in “First Aid for Dora” (1923); Anastasia Bates in “The Purification of Rodney Spelvin” (1925); Algernon Aubrey Little in “The Word in Season” (1940; in A Few Quick Ones, 1959); Nobby Hopwood in Joy in the Morning (1946); there may be more.

See also half-pint below, p. 56.

an austere umbrella (p. 22)

A perfect example of a transferred epithet; the usual manner of wording this would be “to prod her austerely in the small of the back with an umbrella.”

every little bit added to what you’ve got (p. 23)

See Cocktail Time.

rickets, rheumatism, sciatica, anaemia, and stomach trouble (p. 24)

Some of these are diseases of poor nutrition; the bone-softening disease rickets can be caused by a lack of Vitamin D, and some of the many forms of anemia can be treated with iron, Vitamin B-12, and folate; of course some forms of stomach trouble can be caused by improper food choices. But the joint pain of rheumatism and the nerve pain of sciatica are not linked with nutrition in the sources I have seen so far.

gilded palace of the rich or the humble hovel of the poor (p. 24)

Diego Seguí finds possible sources as well as other similar phrases in Wodehouse:

In the sequestered cottage of the peasant, whose humble roof invites not the traveller’s approach, she [happiness] is often a constant guest; while she flies the gilded palaces of the rich, the voluptuous, and the powerful.

“The Hermit” in Universal Magazine, December 1773.

[Science in America] irradiates the dark retreats of indigence, and sheds its vivifick beam as well on the humble cottage of the poor, as on the gilded palace of the rich.

Daniel Knight: An Oration…on the Forty-Third Anniversary of American Independence (1819)

I receive a tolerably satisfactory salary each week, and in return I spread the good word about Nervino in the gilded palaces of the rich.

Jill Mariner’s Uncle Chris, in The Little Warrior (1920)

“Donaldson’s Dog Joy,” he said, a hand stealing to his hat as if he were about to bare his head, “is God’s gift to the kennel, whether it be in the gilded palace of the rich or the humble hovel of the poor.”

Freddie repeats his sales pitch in “Life With Freddie” (in Plum Pie, 1966/67)

both feet on the ground (p. 24)

This phrase for a practical, down-to-earth stance is more common in Wodehouse than I had previously noticed. Of course applying it to a four-footed animal adds a touch of humor.

A fine, upstanding dog, with eyes sparkling with the joy of living and both feet on the ground.

“The Go-Getter” (1931; in Blandings Castle and Elsewhere, 1935)

The female of the species, however, appeared unwilling to take this thing lying down. Her chin was up, her shoulders were squared, she had both feet on the ground, and she looked the troupe steadily in the eye through her spectacles.

“Fate” (1931; in Young Men in Spats, 1936)

Bertram Wooster is a man who likes to go through the world with his chin up and both feet on the ground, not to sneak about on tiptoe with his spine tying itself into reef knots.

The Code of the Woosters, ch. 7 (1938)

And all the trees which had not both feet on the ground had been uprooted by Carol, so that Edna’s efforts were something of an anti-climax.

“Armadillos, Hurricanes and What Not” in Over Seventy (1957)

It was one of those up-and-coming young smells which keep their chins up and both feet on the ground, the sort of smell that looks you in the eye and gets things done.

“Our Man in America” (Punch, January 11, 1961)

In the circles in which she moved Dolly Molloy was universally regarded as a tough baby who kept her chin up and both feet on the ground, and a good deal of envy was felt of Soapy for having acquired a mate on whom a man could rely.

The Ice in the Bedroom, ch. 23 (1961)

“Standing as straight as an arrow with my chin up and both feet on the ground.”

Frozen Assets/Biffen’s Millions, ch. 4.3 (1964)

…its noble scenery, its wide-open spaces, its soft mountain breezes and its sun-drenched pleasaunces impart to the jaded city worker a new vim and vigor and fill him so full of red corpuscles that before a day has elapsed in these delightful surroundings he is conscious of a je ne sois quoi and a bien être and goes about with his chin up and both feet on the ground, feeling as if he had just come back from the cleaner’s.

“Sleepy Time” (in Plum Pie, 1967)

Compare:

With my shoulder to the wheel / And my two feet on the ground!

Ira Gershwin, lyric for “Typical Self-Made American” (from Strike Up the Band, 1927)

five-shilling packet (p. 24)

Five shillings is one-fourth of a pound sterling. The Bank of England inflation calculator suggests a factor of about 31 to account for inflation from 1947 until late 2022, so in present-day terms this would be the rough equivalent of £8 or US$12.

soul in torment (p. 25)

The phrase can be traced in English at least as far back as the 1687 translation of Cervantes’s Don Quixote:

If thou art a Soul in Torment, tell me, and thou shalt not want the Consolation of what Assistance I can give thee.

Wodehouse used it at least as early as The White Hope (1914).

Solomon (p. 26)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

bisques (p. 26)

Essentially meaning “bonus points” here; derived from an informal style of giving a handicap advantage to a weaker golfer; see A Glossary of Golf Terminology on this site.

prognathous (p. 26)

Having a prominent or jutting jaw. Apparently the only time Wodehouse used the word, so far as can be found.

Diego Seguí notes that Wodehouse also used the even rarer converse of the word, opisthognathous, meaning having teeth or jaws pointing backward, or in a humorous sense, weak-chinned. Wodehouse is cited in the OED for a letter of 30 November 1937 in The Times:

Compared with Sir Roderick Glossop, Tuppy Glossop, old Pop Stoker, Mr. Blumenfeld, and even Jeeves, Bertie is undoubtedly opisthognathous.

gorilla (p. 26)

Other Wodehouse characters whose looks or actions are compared to that of a gorilla include Reggie, Lord Havershot in Laughing Gas (1936) [taking after his late father]; Alf Todd in “The Return of Battling Billson” (1923; in Ukridge, 1924); P. C. Edward Plimmer in “The Romance of an Ugly Policeman” (1915); Sidney McMurdo in “Scratch Man” (in A Few Quick Ones, 1959); Senator Opal in Hot Water, ch. 2.5 (1932); Battling Billson himself in Something Fishy, ch. 4 (1957); and Roderick Spode in Much Obliged, Jeeves, ch. 7 (1971).

bunce (p. 28)

Money or other benefit, especially when unexpected or when received as a bonus.

“…I’ve nearly broken my leg.”

He started. A fanatic gleam came into his eyes. He looked like a boy confronted with an unexpected saucer of ice cream.

“I say! Have you really? This is a bit of bunce. I can give you first aid.”

Bertie and Edwin Craye in Joy in the Morning, ch. 9 (1946)

young peanut (p. 29)

Not one of Wodehouse’s more common epithets for a diminuitive young woman.

“Isn’t that enough of a treat for a small girl about half the size of a peanut?”

Lord Biskerton to Kitchie Valentine, in Big Money, ch. 5 (1931)

“And that’s what makes it seem so strange that a little peanut like you keeps giving him the push.”

Augustus Robb to Terry Cobbold, in Spring Fever, ch. 17 (1948)

acutely alive to the existence of class distinctions (p. 29)

This appears to be a Wodehouse coinage, first appearing as Jeeves describes Harold, the page boy, in “The Purity of the Turf” (1922; in The Inimitable Jeeves, 1923):

“He is somewhat acutely alive to the existence of class distinctions, sir.”

Plum used the phrase a few more times, and it has been widely quoted from him by other writers.

“But even so, the duke is a man acutely alive to the existence of class distinctions, and I think that as a wife for his nephew he would consider the daughter of a brain specialist hardly—”

Uncle Fred in the Springtime, ch. 12 (1939)

They tell me he is rather acutely alive to class distinctions and being on the castle payroll has always looked down on the Church Lads as social inferiors.

Service With a Smile, ch. 6.2 (1961)

[Lord Tilbury] was a man rather acutely alive to class distinctions and he felt that Percy, liberally pimpled and favoring the sort of clothes that made him look like a Neapolitan ice cream, would not do him credit at his club.

Frozen Assets/Biffen’s Millions, ch. 6.1 (1964)

il promessi sposi (p. 29)

Freddie makes a mistake in the Italian for “the promised spouse” (one’s fiancé); it should be il promesso sposo in the masculine singular. He was probably led astray by the title of an 1827 novel by Manzoni, I promessi sposi, also the title of an 1856 opera by Ponchielli based on the novel; in those works the title refers to an engaged couple, so all the words of the title are in the plural.

noblesse (p. 29)

A French word borrowed directly into English; here meaning simply the peerage, the nobility.

kind hearts … are more than coronets (p. 30)

See Blandings Castle.

Registry Office (p. 30)

Wodehouse uses this term in two different ways: as an employment office for hiring servants, as in “Jeeves Takes Charge” (1916), and sometimes, as here, for what he more often names as a registrar’s office, for marriages: see The Inimitable Jeeves.

The Brompton Road Registry Office seems to be found only in Wodehouse or quotations from this book.

fait accompli (p. 30)

French for “an accomplished fact”; used in English since 1845.

skimmed around the corner (p. 31)

Although we know that Freddie and Aggie were married in London (see “The Custody of the Pumpkin”), your annotator cannot help thinking this phrase was influenced by Wodehouse’s own marriage to Ethel, at The Little Church Around the Corner (formally The Church of the Transfiguration) in New York City in 1915.

stinker (p. 32)

The OED calls this a figurative sense, slang for “a strongly-worded letter; a disagreeable review or other communication”; the earliest citation is from 1912.

Wodehouse is cited in the OED as an example, from “The Luck of the Stiffhams” (1933; in Young Men in Spats, 1936):

For weeks and weeks, you see, Stiffy had been yearning to write an absolute stinker to old Wivelscombe, telling him exactly what he thought of him.

up by twelve (p. 32)

Prudence seems to be under the impression that marriages still had to take place before noon, though this restriction had long been relaxed. See A Damsel in Distress.

vanish on a jag (p. 32)

Go on a drinking spree. The word jag originally meant as much liquor as one can consume, then generalized to a bout of being drunk; in colloquial usage since the seventeenth century, deriving from a dialect word for a carter’s or peddler’s load.

local yokels (p. 33)

The word yokel, of uncertain origin, is cited in British literature beginning in 1819, with the sense of a country bumpkin, a humorous rural character. The rhyming phrase above shows up in comic journals like Punch and Fun in the 1870s.

placed end to end (p. 33)

More familiarly imagined as a row of people:

On the cricket field: If the number of assistant-under-secretaries of county clubs were placed end to end they would reach from Hyde Park Corner to Peckham Rye.

The Globe By the Way Book (1908)

Statisticians have estimated that if all the grandmothers alone who perished between the months of April and October that year could have been placed end to end they would have reached considerably further than Minneapolis.

“The Pitcher and the Plutocrat” (1910)

It is estimated that if all the young playwrights in New York were placed end to end they would reach from Yonkers to within a foot or two of the Battery.

“Drawbacks of the Drama in England” (1922)

This one is the best-remembered of all, and quoted in later books as well:

“Do you know,” said a thoughtful Bean, “I’ll bet that if all the girls Freddie Widgeon has loved and lost were placed end to end—not that I suppose one could do it—they would reach half-way down Piccadilly.”

“Further than that,” said the Egg. “Some of them were pretty tall.”

“Good-bye to All Cats” (1934; in Young Men in Spats, 1936)

I suppose if the young lovers I’ve known in my time were placed end to end—difficult to manage, of course, but what I mean is just suppose they were—they would reach halfway down Piccadilly.

Joy in the Morning, ch. 16 (1946)

Statistics show that the number of authoresses kissed annually by publishers is so small that, if placed end to end, they would reach scarcely any distance.

Uncle Dynamite, ch. 14 (1948)

Take, for instance, that book The Swoop, which was one of the paper-covered shilling books so prevalent around 1909. I wrote the whole twenty-five thousand words of it in five days, and the people who read it, if placed end to end, would have reached from Hyde Park Corner to about the top of Arlington Street. Was it worth the trouble?

Over Seventy, ch. 6 (1957)

The rosy cheeks and sparkling eyes to be seen in Detroit would reach, if placed end to end, for miles and miles and miles.

“America Day by Day” (in Punch, June 4, 1958)

“The couples I’ve brought together in my time, if placed end to end, not that I suppose one could do it, of course, would reach from Piccadilly Circus to well beyond Hyde Park Corner.”

Lord Ickenham in Cocktail Time, ch. 9 (1958)

But the earliest uses in Wodehouse were of smaller things:

“Dear, dear,” mused the Banshee, who had a taste for statistics, “the hairs I have turned white in single nights in that room would reach, if placed end to end, from Paris to London.”

“The Baffled Banshee” (1903)

If the tail-feathers of all the parrots present in the French Saloon of the St. James’ Restaurant yesterday afternoon could be placed end to end they would reach part of the way to the North Pole.

“Screech Day” (1903)

If the Trust’s stock of lines were to be placed end to end it would reach part of the way to London.

“A Corner in Lines” (1905)

rock-bound coast of Maine (p. 33)

Probably influenced by a Hemans poem: see Very Good, Jeeves.

nautch girl (p. 33)

A professional dancing girl of India.

guerdon (p. 33)

An old-fashioned word for “reward”.

young dogface (p. 34)

Freddie is using some license with his cousin Prudence; this is the only instance so far found where the epithet applies to a young woman. More commonly used by one young man to another, as with Bertie Wooster’s cousin Eustace introducing Lord Rainsby in “Sir Roderick Comes to Lunch”, or by a modern girl to her young man, as Muriel Branksome to Sacheverell Mulliner in “The Voice from the Past” (1931; in Mulliner Nights, 1933).

Diego Seguí notes that Bertie Wooster says that Emerald Stoker looks like a Pekinese in Stiff Upper Lip, Jeeves (1963), but no one calls her “dogface” in that book.

Park Hotel (p. 34)

Apparently intended fictitiously; the current-day hotel of the same name in London is in Belgrave Road.

sow the good seed (p. 34)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

sleeve across the windpipe (p. 34)

Literally, a choke hold executed from behind the victim, reaching over the shoulder and applying pressure on the trachea with the attacker’s forearm. Figuratively, an assault or severe blow, especially one that detains a victim. See The Mating Season for the probable source.

charmers … deaf adder (p. 35)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

Barribault’s Hotel (p. 35)

See Ice in the Bedroom.

roopy (p. 35)

Hoarse or husky; a figurative adaptation from roup, a respiratory disease affecting birds. See Love Among the Chickens.

medicine man (p. 36)

shake like an aspen (p. 36)

See Right Ho, Jeeves.

alcohol’s a tonic (p. 37)

Many of Wodehouse’s characters share this opinion; among others see Bertie Wooster (“bracer” in The Inimitable Jeeves, 1923). See also “restorative” in Sam the Sudden (1925).

Sir Abercrombie Fitch-Fitch (p. 37)

An echo of the New York sporting goods store Abercrombie & Fitch; clearly Wodehouse enjoyed the sound of the names of the founders. See Lord Emsworth and Others for other references to the name.

E. Jimpson Murgatroyd (p. 37)

The gloomy doctor will make another appearance in Aunts Aren’t Gentlemen, ch. 1 (1974), when Bertie Wooster consults him for spots on his chest, having recalled that Tipton Plimsoll had mentioned that the doctor’s treatment for the same ailment had done him good.

Other than Tipton’s former fianceé Doris Jimpson, he is the only Wodehouse character with this as part of his name. Wodehouse does mention the name in connection with a poisonous weed:

…it is no light matter, my lad, to be caught having correspondence with a human Jimpson weed like you.

Letter from Sally to Ginger Kemp in The Adventures of Sally, ch. 12 (1921/22)

Most sources spell the common name for Datura stramonium as “jimson weed,” however.

For the surname Murgatroyd, see Summer Lightning.

Chapter Three

Runs from p. 38 to p. 70 in the 1947 Doubleday edition.

iodoform (p. 38)

See Young Men in Spats.

shoulder-to-shoulder stuff … Boys of the Old Brigade (p. 39)

Not the Irish Republican song commemorating the 1916 Easter uprising, perhaps better known today due to controversy, but a reference to The Old Brigade, a slow march composed in 1881 by Edward Slater with words by Frederic Weatherly.

Where are the boys of the old Brigade,

Who fought with us side by side?

Shoulder to shoulder, and blade by blade,

Fought till they fell and died!

Who so ready and undismayed?

Who so merry and true?

Where are the boys of the old Brigade?

Where are the lads we knew?

Then steadily shoulder to shoulder,

Steadily blade by blade!

Ready and strong, marching along

Like the boys of the old Brigade!

Wodehouse had alluded to this song as early as 1901 in an “Under the Flail” column in the Public School Magazine, as well as in The White Feather (1905/07), so the nineteenth-century song must have been the one he knew.

Seeing things. (p. 41)

The UK first edition leaves out this, the middle of the three short lines in the US edition, and has, between the longer paragraphs above and below, simply:

Seeing things?

What sort of things?

guineas (p. 41)

See Ukridge. Three guineas in 1947 had a rough equivalent purchasing power to £130 or US$165 in 2022 values.

smackers (p. 41)

The term, originally American slang, has been used by Wodehouse and other writers for both dollars and pounds (see Bill the Conqueror); this is the only time so far found where it refers to guineas.

applesauce (p. 42)

See Bill the Conqueror.

talking through his hat (p. 42)

Speaking nonsense, making foolish remarks. The OED has citations beginning in 1888 in America.

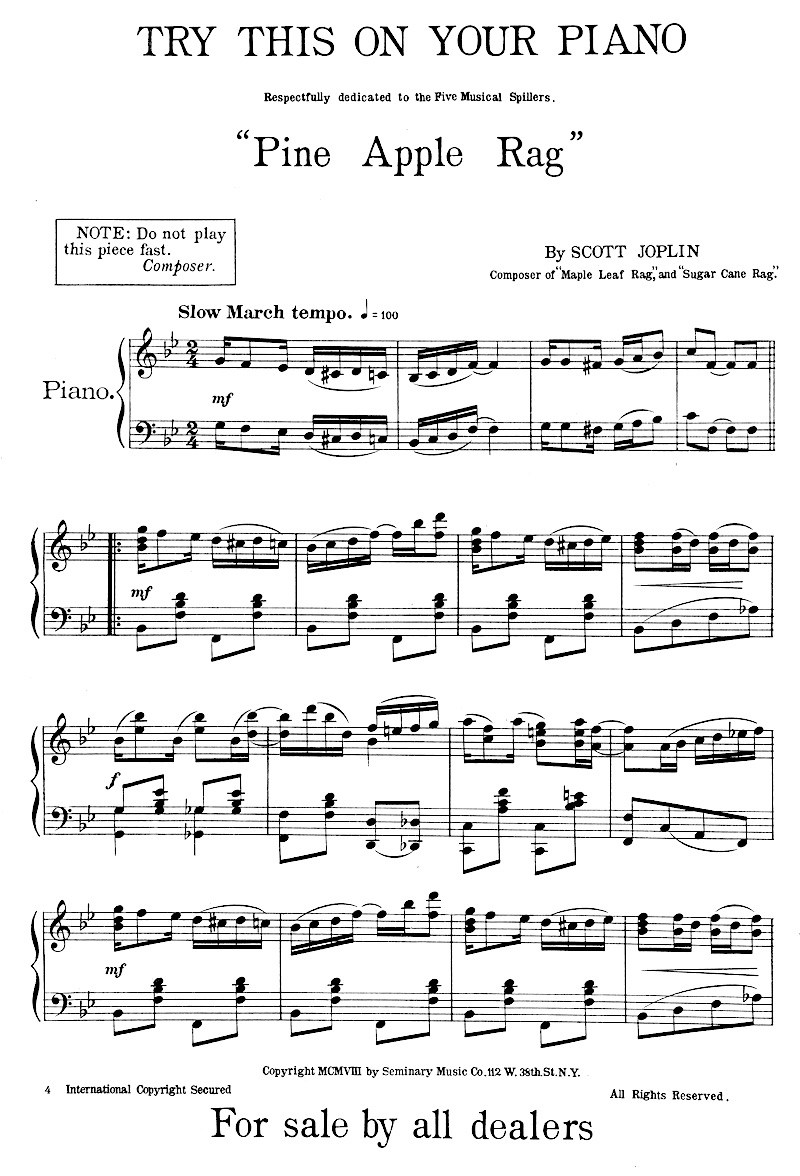

Try that on your bazooka (p. 43)

Not the portable tubular rocket-launcher invented in World War II, but the humorous musical instrument after which it is named, an invention of American comedian Bob Burns (1890–1956). Newsweek described it in 1935 as “a trombone-like instrument confected of two gas-pipes and a whisky funnel.”

Not the portable tubular rocket-launcher invented in World War II, but the humorous musical instrument after which it is named, an invention of American comedian Bob Burns (1890–1956). Newsweek described it in 1935 as “a trombone-like instrument confected of two gas-pipes and a whisky funnel.”

The phrase is a variant on the sarcastic saying “Try that on your piano!”—like “Put that in your pipe and smoke it,” it is a challenge, a colloquialism for “Think it over and see how you like it” or “Reply to that if you can.” This in turn refers to advertisements in popular sheet music, where excerpts from other songs from the same publisher might appear on the back cover of the sheet music, with the headline “Try this on your piano” or something similar.

Lister, William Galahad (p. 43)

We learned from Prudence in Chapter Two (p. 26) that Bill Lister is Galahad’s godson, but this is the first indication that his middle name is the given name of his godfather.

“Anything goes” (p. 43)

That phrase had a special meaning for Wodehouse, as he and Guy Bolton had written the original book for the 1934 Cole Porter musical comedy of that name. It was substantially revised before production by Howard Lindsay and Russel Crouse.

ringside pews (p. 44)

This is not the first time Wodehouse drew parallels between a church and a boxing arena. See the notes to “The Return of Battling Billson” in Ukridge.

morning-coated (p. 44)

For a full description of formal morningwear, see spats in the notes to Right Ho, Jeeves.

screwed up his courage to the sticking point (p. 44)

See Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse for the lines from Macbeth alluded to here.

piece of cheese (p. 44)

Late nineteenth-century slang for an unpleasant, stupid, or incompetent person. Wodehouse used it for Washy McCall in “Washy Makes His Presence Felt” (1920; in Indiscretions of Archie, 1921) and for Mrs. Smethurst’s opinion of Cuthbert Banks in “The [Unexpected] Clicking of Cuthbert” (1921).

plenipotentiary (p. 45)

An ambassador or diplomat entrusted with full authority to make treaties, contracts, and the like on behalf of a ruler or nation.

hand and feet … elephantiasis (p. 45)

See The Girl on the Boat.

tramp cyclist (p. 45)

See The Mating Season.

ex-King of Ruritania (p. 45)

See Blandings Castle.

bimbo (p. 46)

See Money for Nothing.

Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego (p. 47)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

medical Jeremiah (p. 48)

A pessimistic doctor. See Money for Nothing.

as the hart pants… (p. 48)

See Young Men in Spats.

like the crackling of thorns under a pot (p. 49)

heart … stood still (p. 49)

Wodehouse here gives his own annotation to this phrase. But he had used it twice in the narrative voice of Jeremy Garnet in the 1909 USA version of Love Among the Chickens.

working away at the old stand (p. 49)

See Bill the Conqueror.

downed tools (p. 49)

The phrase is typically used for industrial workers who lay down their implements of work and go on an immediate or “lightning” strike. (See also p. 212 below.) Cited in the OED from 1855 onward, but described as rare in American usage.

eyes came out of his head like a snail’s (p. 49)

See Thank You, Jeeves.

there with his hair in a braid (p. 51)

See The Mating Season.

feeling like thirty cents (p. 51)

See Cocktail Time.

Beaumont Street (p. 52)

Wodehouse is clearly mixing up his London locations in order not to pin the action to a specific district; the only Beaumont Street in central London is in Marylebone, nowhere near the Brompton Road which is mostly in Knightsbridge. There is mild humor in the idea of the Brompton Road Registry Office being located in Beaumont Street, but this does not seem to be a plot point in the way that the Milton Street/Wilton Street confusion is used in Service With a Smile.

In Bill the Conqueror, ch. 22, the address of a registry office at 11 Beaumont Street, Pimlico, is given, but there is no Beaumont Street in Pimlico either.

buck-and-wing dance (p. 52)

See Money in the Bank.

pea under the thimble (p. 52)

Peep-Bo (p. 53)

See Summer Lightning.

park … Serpentine (p. 53)

The Serpentine is an artificial ornamental lake of 40 acres in Hyde Park, London, created in 1730 at the request of Queen Caroline.

a perplexed monocle (p. 55)

Another transferred epithet.

chronicler (p. 55)

See Cocktail Time.

nerves … sticking out of his body (p. 55)

Compare Bertie Wooster’s condition:

…my nerves, which had been sticking out of my body an inch long and curled at the ends, gradually slipped into place again.

Thank You, Jeeves, ch. 15 (1934)

binge (p. 56)

Here, in the sense of “scheme”; see The Code of the Woosters.

half-pint (p. 56)

As with half-portion above, p. 22, this also describes a small person.

Jane Abbott, that wonder girl in whose half-pint person were combined all the lovely qualities of woman…

Summer Moonshine, ch. 17 (1938)

Ivor Llewellyn calls Sandy Miller a half-pint in The Plot That Thickened (1973). (In the equivalent UK book, Pearls, Girls and Monty Bodkin (1972), he refers to her as “the half measure.”) Lord Uffenham calls Chimp Twist “you ghastly-looking little half pint of misery” in Money in the Bank (1942).

Queen of Sheba (p. 56)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

sucked the knob of his umbrella (p. 56)

See Laughing Gas.

angel in human shape (p. 57)

See Laughing Gas for a discussion of the phrase. Wodehouse was fond of it and used it many times:

“I tell you, Bertie, Angela’s all right. An angel in human shape, and that’s official.”

“The Ordeal of Young Tuppy”/“Tuppy Changes His Mind” (1930; in Very Good, Jeeves)

“She is so small, so sweet, so dainty, so lively, so viv——, what’s-the-word?—that a fellow wouldn’t be far out in calling her an angel in human shape.”

“Aren’t all angels in human shape?”

“Are they?” said Percy, who was a bit foggy on angels.

“The Amazing Hat Mystery” (1933; in Young Men in Spats, 1936)

Every word that she uttered made me more convinced that I was in the presence of an angel in human shape.

Laughing Gas, ch. 2 (1936)

He rather imagines that Purkiss must have thought he had run up against an angel in human shape or something.

“Bingo and the Peke Crisis” (1937; in Eggs, Beans and Crumpets, 1940)

“If H. Bostock isn’t an angel in human shape, then I don’t know an angel in human shape when I see one.”

Uncle Dynamite, ch. 2 (1948)

Somewhere in the world, he had told himself, there must be angels in human shape willing to put money into a shaky publishing firm.

Otis Painter in Uncle Dynamite, ch. 14.1 (1948)

“An angel in human shape, didn’t you think?”

The Mating Season, ch. 6 (1949)

Then he reflected that if you couldn’t confide in an angel in human shape, who could you confide in?

“How’s That, Umpire?” (in Nothing Serious, 1950)

More like an angel in human shape he seemed to me.

“Hi, Bartlett!”, §2, in America, I Like You (1956)

“You’ve saved two human lives from the soup, and you can quote me as stating this, that if ever an angel in human shape…”

Ice in the Bedroom, ch. 26 (1961)

“She’s an angel in human shape. I spotted her solid merits the moment I saw her.”

Stiff Upper Lip, Jeeves, ch. 7 (1963)

Gladys was as nearly as made no matter an angel in human shape, but she was inclined, like so many girls who have what it takes, to be imperious and of a trend of mind to resent hotly anything in the nature of what might be called funny business.

“A Good Cigar Is a Smoke” (1967; in Plum Pie)

“All,” said Jill, “except to tell you, Mr. Appleby, that you are an angel in human shape.”

Do Butlers Burgle Banks?, ch. 15 (1968)

small boy in buttons (p. 58)

See Bill the Conqueror.

blancmange (p. 59)

A quivery molded cold dessert, made of flavored and sweetened milk stiffened with starch or gelatin.

Paddington (p. 60)

See Uncle Fred in the Springtime.

express (US only, p. 60)

An express train makes only a few stops along its run, for faster service between major stations. The UK book omits this word.

Market Blandings (p. 60)

A fictitious town in Shropshire, two miles from Blandings Castle, large enough to be a local center of farming commerce, but not in the class of Shrewsbury when it comes to shopping for gifts for Veronica.

Swindon (p. 60)

The largest town in Wiltshire, on the main line of the Great Western Railway.

dumb chums (p. 61)

lilso ribbon (p. 61)

This phrase is found nowhere else in an Internet search, although it appears thus in both US and UK first editions. Diego Seguí plausibly suggests that this is a typographical error for “lilac ribbon” as used elsewhere by Wodehouse:

McCay was the sort of man who keeps old ball programs and bundles of letters tied round with lilac ribbon.

“Archibald’s Benefit” (1910; in The Man Upstairs, 1914)

Removing this, he disclosed a layer of newspaper, then another, and finally a formidable typescript bound about with lilac ribbon.

Sam the Sudden, ch. 29.1 (1925; serialized as Sam in the Suburbs, section XLII)

“She then handed back my letters, which she was carrying in a bundle tied round with lilac ribbon somewhere in the interior of her costume, and left me.”

“The Letter of the Law” (1936; in Lord Emsworth and Others, 1937)

Diego notes that the Overlook Press edition of 2006 adopted the “lilac ribbon” reading.

Norman blood (p. 61)

That is, aristocratic ancestry deriving from the Norman French invaders under William the Conqueror. Frequently mentioned in references to a Tennyson poem: see Thank You, Jeeves.

Devil’s Island (p. 62)

See Uncle Fred in the Springtime.

cooler … jug (p. 62)

American slang words for prison, dating from the nineteenth century.

Roman emperor (p. 62)

See Something Fishy for more Wodehouse characters so described.

infinite resource and sagacity (p. 62)

See Sam the Sudden.

here, if I mistake not, Watson, is our client now (p. 62)

See Thank You, Jeeves.

one of the nibs (p. 63)

19th-century British slang: one of the aristocrats.

Joe Louis (p. 63)

In full, Joseph Louis Barrow (1914–81), American boxer, nicknamed the Brown Bomber. He was world heavyweight champion from 1934 to 1951, so would indeed have been a celebrity at the time of this book.

skittle sharps (p. 65)

See Summer Lightning.

jellied eel sellers (p. 65)

See Ukridge.

thrown in the towel (p. 65)

See Right Ho, Jeeves.

Harrogate and Buxton (p. 65)

Harrogate is a spa town in Yorkshire; Buxton is a spa in the Derbyshire Peak District. Both are renowned for their mineral waters, both for drinking and bathing, as a “cure” for the aftereffects of rich living.

rising on steppingstones (p. 65)

A humorously altered allusion to Tennyson: see Something Fresh for the original lines.

The UK first edition hyphenates “stepping-stones” here.

His eye was not dimmed nor his natural force abated (p. 65)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

settled his little flock (p. 65)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

half a crown (p. 65)

See Summer Lightning. This is half of the price of the five-shilling packet of cigarettes mentioned above, p. 24.

omitting no detail, however slight (p. 66)

See Right Ho, Jeeves.

nice bit of box fruit (p. 66)

See Laughing Gas.

on the Halls (p. 66)

Music halls or Vaudevilles were theatres specialising in variety entertainment, and usually also serving food and drink to a mainly lower-class public. They were thus a considerable step down in respectability even from the “legitimate theatre.” [MH]

Emsworth Arms (p. 66)

See Summer Lightning.

Erbert/’Erbert (p. 66)

Either spelling indicates that Herbert drops his aitches when he speaks. The US text has plain Erbert; the UK book has ’Erbert to make it clearer that a letter has been dropped out.

side (p. 67)

Chiefly British colloquialism for conceit, arrogance, affectation, pretentiousness. Not, perhaps, what one would expect to find in any case in one in the lowly occupation of potboy. The OED cites Wodehouse in Right Ho, Jeeves, ch. 11 (1934), in which Bertie is slanging Tuppy Glossop to Angela:

“A frightful oik, and a mass of side to boot.”

stinker (p. 67)

See p. 32, above.

long-felt want (p. 67)

The phrase became popular in English beginning in the middle of the nineteenth century, and by 1900 had become a cliché of advertising, suggesting that a new product filled a long-standing desire.

Wodehouse used it as the title of an item in Punch in 1903; to describe Corven Abbey in Chapter III of The Gem Collector (1909) and Dreever Castle in a parallel passage in The Intrusion[s] of Jimmy/A Gentleman of Leisure, ch. 8 (1910); to describe a proposed new style of writing in “The Literature of the Future” (1914); and to describe “Mulliner’s Buck-U-Uppo” (1926).

They sighed for fresh worlds to conquer. And Thomas Blake supplied the long-felt want.

Not George Washington, ch. 10 (1907)

A ghark is anything that makes you feel horrid and uncomfortable. It was a word invented by some girls I know, the Moncktons, and it supplied a long-felt want.

“Ladies and Gentlemen v. Players” (1908)

“What’s that?” said Scott. “The Rapier? I did glance at it. It seemed to me to supply a long-felt want. Fill an obvious void, if you know what I mean.”

“Pillingshot’s Paper” (1911)

Mulliner’s Buck-U-Uppo is of two grades or qualities—the A and the B. The A is a mild, but strengthening, tonic designed for human invalids. The B, on the other hand, is purely for circulation in the animal kingdom, and was invented to fill a long-felt want throughout our Indian possessions.

“Mulliner’s Buck-U-Uppo” (1926)

The Garrity at Columbus Circle spoke highly of a Garrity near the Battery, and the Garrity at Irving Place seemed to think his cousin up in the Bronx might fill the long-felt want.

The Small Bachelor, ch. 12 (1926/27)

“Lord Emsworth’s brother, Galahad Threepwood, has written his Reminiscences.”

“I know. I’ll bet they’re good, too. They would sell like hot cakes. Just the sort of book to fill a long-felt want.”

Heavy Weather, ch. 7 (1933)

The Argus Inquiry Agency, whose offices are in the south-western postal district of London, had come into being some years previously to fill a long-felt want . . . a want on the part of Percy Pilbeam, its founder, for more money.

Something Fishy/The Butler Did It, ch. 19 (1957)

Briefly what has happened is that, sensing a long-felt want, they have put on the market a portable martini cocktail.

The 3M company in “P. G. Wodehouse glances at the American scene” in Punch, December 24, 1958

Writers through the ages have made a good many derogatory remarks about money, and one gets the impression that it is a thing best steered clear of, but every now and then one finds people who like the stuff and one of these was Jane. It seemed to her to fill a long-felt want.

The Girl in Blue, ch. 11.2 (1970)

guv’nor (p. 67)

British slang for a person in authority over the speaker, in Wodehouse especially referring to one’s father.

Dog Joy (p. 67)

Beginning at this point the US first edition omits the hyphen; all earlier references are to Dog-Joy.

joint (p. 68)

See Sam the Sudden.

Messmore Breamworthy (p. 68)

Besides borrowing his name for an alias for Bill Lister, the name is mentioned again in Sunset at Blandings as a possible alias for Jeff Bennison.

Fruity Biffen (p. 69)

This is Gally’s first mention of his old friend from the Pelican Club. In Pigs Have Wings (1952) he is referred to as Admiral Biffen and “he used to sign his I.O.U’s George J. Biffen” (though in a later chapter his initials are misprinted as “C. J.”). Recalled again in A Pelican at Blandings (1969) and Sunset at Blandings (1977) for the incident when his false beard came off unexpectedly.

Hurst Park (p. 69)

See Carry On, Jeeves.

Assyrian (p. 69)

Diego Seguí notes that Wodehouse is thinking of the long braided beards in statues and bas-reliefs, like the one of Sargon II at right. He finds other references to Assyrian beards in Bring On the Girls, referring to composer Ivan Caryll, and in Author! Author!, referring to a sailor in his internment camp (letter of November 1, 1946).

Diego Seguí notes that Wodehouse is thinking of the long braided beards in statues and bas-reliefs, like the one of Sargon II at right. He finds other references to Assyrian beards in Bring On the Girls, referring to composer Ivan Caryll, and in Author! Author!, referring to a sailor in his internment camp (letter of November 1, 1946).

stewed to the eyebrows (p. 70)

Completely drunk; see Right Ho, Jeeves.

Chapter Four

Runs from p. 71 to p. 91 in the 1947 Doubleday edition.

three hours and forty minutes (p. 71)

In Wodehouse’s introduction to a 1968 reprint of Something Fresh, he told us that the train journey from London to Blandings took about four hours. Since here we are told that the total trip for Prudence was more like four hours and a quarter, either the train was not fast that day or she had to wait at Market Blandings station for the car from the castle to come pick her up and take her the last two miles of the journey.

Parisian Four Arts Ball (p. 71)

In French, Bal des Quat’z’Arts, held annually in Paris from 1892 through 1966; originally organized by Professor Henri Guillaume of the École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts for students of architecture, painting, sculpture, and engraving. From the second year onward, it gained a Bohemian reputation, with costumed and a few completely uncostumed revelers dancing and drinking till dawn.

a man with such a map (p. 71)

Slang for “face”; see The Clicking of Cuthbert.

smell of boiling cabbage (p. 72)

See Bill the Conqueror.

serve her sentence (p. 72)

Another allusion to Blandings Castle as a prison for misbehaving young people; compare Devil’s Island, cooler, and jug on p. 62 above.

loved not wisely but too well (p. 72)

See Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse for this and many other references to this line from Othello.

his study was going to be tidied again (p. 72)

The immediate reference:

“I have been tidying your study, Uncle Clarence,” she replied listlessly. “It was in a dreadful mess.”

Lord Emsworth winced as a man of set habits will who has been remiss enough to let a Little Mother get at his study while his back is turned, but he continued bravely on the cheerful note.

“Company for Gertrude” (1928; in Blandings Castle and Elsewhere, 1935)

It will happen again:

“And what she has done to my study! It stinks of disinfectant and I can’t find a thing.”

“Yes, I saw her tidying it up.”

“Messing it up, you mean.…” said Lord Emsworth.

Lord Emsworth to Galahad about Sandy Callender in Galahad at Blandings, ch. 6.1 (1965)

And others suffer this as well:

You were out, but Peasemarch let her in and parked her in the study. After nosing about a while, she started, as women will, to tidy your desk.

Lord Ickenham to Sir Raymond Bastable in Cocktail Time, ch. 4 (1958)

Blandings Parva (p. 72)

A village near the castle, smaller than Market Blandings. Parva comes from the Latin word parvus, meaning “small.”

Gertrude … doing her stretch (p. 72)

From “Company for Gertrude” (1928; in Blandings Castle and Elsewhere, 1935) as quoted two notes above. The curate in question is Beefy Bingham.

hitting fungoes (p. 72)

In baseball, using a long, lightweight bat to hit fly balls to fielders for warmup and practice. A coach can toss a ball lightly upward with one hand and hit it to the fielder with a fungo bat more easily than hitting balls pitched at him using a standard bat.

Diego Seguí notes that it is a bit odd that Lord Emsworth should be thinking in baseball terms.

midseason form (p. 73)

Commonly used by Wodehouse to describe someone in peak condition, as a sportsman who is neither raw from lack of practice at the beginning of a sporting season nor tired out from overwork near the end of it. The OED has many citations for “midseason,” but the only one where it is coupled with “form” is from Wodehouse, in Indiscretions of Archie, ch. 9 (1921):

“I was just putting old Bill through it,” he explained, “with a view to getting him into mid-season form for the jolly old pater.”

Sugg’s Soothine (p. 74)

One of many fictitious patent medicines invented by Wodehouse. See If I Were You and Money for Nothing.

Lucknow (p. 74)

See Money for Nothing.

he was there forty ways from the jack (p. 74)

An American slang phrase, from card games, meaning “in every way possible.” Wodehouse had used the shorter version “there forty ways” twice earlier:

…when it came to beating up a sparring-partner and an amateur at that, Bugs Butler knew his potentialities. He was there forty ways and he did not attempt to conceal it.

The Adventures of Sally, ch. 13.4 (1921/22)

His four-days’ acquaintance with the bard had been sufficient to show him that the man was there forty ways when it came to writing about love.

Sam Marlowe about Tennyson in The Girl on the Boat/Three Men and a Maid (1921/22)

With “there” the phrase signifies being prepared for or covering all situations. Wodehouse could have learned this shorter version from Damon Runyon or H. C. Witwer:

He was there forty ways with a sap and gat, and he’d shoot as quick as he’d slug.

Runyon: “The Informal Execution of Soupbone Pew” (Adventure, March 1911, p. 904)

Take it from me, that bird is there forty ways.

Witwer: Kid Scanlon (1920, p. 273)

Stephen Fitzjohn alerts us to an early use of the longer phrase without “there”:

It’s hell forty ways from the Jack. It’s tough for me.

Eugene Walter: The Easiest Way (play, 1908; novel, 1911; several films including the last one at MGM in 1931 when Wodehouse was a screenwriter there [though Brian Taves did not mention the play or film in P. G. Wodehouse in Hollywood])

But the earliest reference to the Jack is from an author frequently cited by Wodehouse, one of his best sources for American slang: George Ade.

He saw himself done up forty ways from the Jack by many a He-Pelican who could not command $8 a week in the Open Market.

Ade: The Girl Proposition (1902)

And an earlier version with “there”

[Clarence] Darrow is not a big man in stature, but he is there forty ways from the jump with the gray matter and the knowledge of what is what.

Letter by L. Jerome to the Editor, The Mixer and Server, November 15, 1906, p. 24

Also see Green’s Dictionary of Slang online for other citations of forms of the phrase. But it appears that Wodehouse may have been responsible for splicing the whole thing together in the form it appears in Full Moon.

mangel-wurzel (p. 74)

(more commonly mangold-wurzel) A type of beet, grown for cattle food.

harps, lutes, and sackbuts (p. 75)

See the explanation of a similar phrase from Summer Lightning in Biblia Wodehousiana. Wodehouse apparently misremembered the passage from the Book of Daniel and substituted lutes (members of a group of plucked string instruments with round-backed bodies, predecessors of the mandolin) for one of the Biblical instruments.

a feast of reason and a flow of soul (p. 75)

See Uncle Fred in the Springtime.

batting .400 (p. 76)

In baseball, getting an average of two hits in every five times at bat, an excellent performance in professional play. The last Major League Baseball player to maintain a season batting average over .400 was Ted Williams of the Boston Red Sox, who hit .406 in 1941.

green-eyed monster (p. 77)

Jealousy. See Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse for the passage from Othello and other references to it.

blush of shame to the cheek of modesty (p. 77)

See Right Ho, Jeeves.

from stem to stern (p. 78)

From head to toe, by analogy with boatbuilding. The stem is the curved upright timber in the bow of a wooden vessel into which the planks of the bow are scarfed, according to the OED.

the blood of a hundred earls (p. 78)

Alluding to a Tennyson poem: see Heavy Weather.

french window (p. 79)

See Summer Lightning.

interest, elevate, and instruct (p. 79)

Compare the similar phrase interest, elevate, and amuse in Leave It to Psmith.

Madame Recamier (p. 80)

See Young Men in Spats.

setting on a roar a table (p. 80)

See Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse for the source of this allusion to Hamlet and other references to the same passage.

the society of his juniors (p. 82)

See Bill the Conqueror.

the quickness of the hand almost deceived the eye (p. 87)

Diego Seguí notes that the hand referred to is not that of a magician, in the usual application of the phrase, but of the “hand” given in marriage; a neat repurposing of stock wording for comic effect.

sighting shot (p. 87)

See Leave It to Psmith.

the work of an instant (p. 88)

See the work of a moment in the notes for A Damsel in Distress.

Rodin’s Penseur (p. 89)

Sometimes known as “The Thinker”; see Summer Lightning.

Chapter Five

Runs from p. 92 to p. 109 in the 1947 Doubleday edition.

the quiet evenfall (p. 92)

From Tennyson’s Maud; see Summer Lightning.

M.F.H. (p. 92)

The title of the owner or controller of a pack of fox hounds, who supervises the kennels and hunting arrangements.

playing ball (p. 92)

In the sense of acting fairly or cooperating in a business deal. First recorded 1903 from the USA, so likely derived from a baseball analogy.

four-leggers (p. 93)

This jocular term for animals, typically horses or dogs, is so rare that the OED takes no notice of it in its definitions or citations. Google Books search finds only a few instances in the late nineteenth century. This is apparently its only appearance in Wodehouse.

apple-pie order (p. 93)

Perfectly tidy and neat. The phrase is of uncertain origin, cited from 1780 onward in the OED. Not to be confused with an apple-pie bed, which seems to be in order but is unusable: see Summer Lightning.

a crushing bolt-from-the-blueness (p. 93)

The nineteenth-century phrase “a bolt from the blue” refers to something as unexpected as a bolt of lightning in a clear blue sky. Wodehouse had used it in that sense as the title of one of his series of stories collected as “A Man of Means” (1914), and in “Pig-hoo-o-o-o-ey!” (1927; in Blandings Castle and Elsewhere, 1935) and “Ukridge and the Home from Home” (1931).

But creating the compound adjective “bolt-from-the-blueness” from the phrase seems to be uniquely a Wodehouse invention; no other instance of the term has yet been found.

had to clutch at a passing knives-and-boots boy (p. 93)

One of the young male servants whose tasks included sharpening knives and polishing boots; he might aspire to become a footman some day. Compare him as a support with a list of items clutched by others who might have fallen: see Ice in the Bedroom.

one-horse town (p. 94)

See Hot Water.

Into each life some rain must fall (p. 94)

See Ice in the Bedroom.

to stiffen the upper lip (p. 94)

See The Girl in Blue.

the low-down from the horse’s mouth (p. 94)

The low-down means inside information, especially if confidential; the OED cites the term first from San Francisco newspapers in 1905 and 1915, next from Wodehouse in Leave It to Psmith. News from the horse’s mouth is racetrack jargon for things only known in the stable, thus also meaning reliable private information.

the height of its fever (p. 94)

side-kick (p. 95)

See Leave It to Psmith.

horn-swoggling (p. 95)

See Ice in the Bedroom.

bimbos (p. 95)

See Money for Nothing.

Hamlet-like despondency (p. 95)

For general references to Hamlet’s character in Wodehouse, see Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse.

on the wagon (p. 95)

See Piccadilly Jim.

some people named Brimble (p. 96)

It is not known if the Shrewsbury Brimbles are related to Mrs. C. Hamilton Brimble and her daughter Hermione, whom we will meet in Barmy in Wonderland/Angel Cake (1952), or to a different Hermione Brimble, daughter of a bishop, who appears in “Joy Bells for Barmy” (1947) and “The Right Approach” (1958).

Mariana at the moated grange (p. 96)

See Cocktail Time.

backing and filling (p. 96)

See Uncle Fred in the Springtime.

the word in season (p. 97)

See Thank You, Jeeves.

looking like Othello (p. 97)

For more general references to Othello’s character, see Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse.

Ouled Nail stomach dancer (p. 98)

See Nothing Serious.

trod on the self-starter (p. 98)

See Bill the Conqueror.

Velasquez (p. 101)

raspberry (p. 102)

See The Girl on the Boat.

cheese mite (p. 103)

A tiny arachnid, Tyrophagus casei, on the order of half a millimeter long, which is deliberately inoculated into certain European cheeses to assist in their curing process. Wodehouse used it a few other times as an example of an extremely tiny living thing:

“If I don’t bean that little cheese mite before I’m much older,” she said, “something’ll crack. My constitution won’t stand it.”

Dolly Molloy, about Chimp Twist, in Money in the Bank, ch. 25 (1942)

“You are going to say that it is not Wooster’s fault that he looks like a slightly enlarged cheese mite.”

The Mating Season, ch. 19 (1949)

“She said that she could make a scratch player out of a cheese mite, provided it had not lost the use of its limbs…”

“Scratch Man” (in A Few Quick Ones, 1959)

“An attractive little cheesemite, isn’t she, Joe?”

“Bill” Shannon about Kay Shannon in The Old Reliable, ch. 9 (1951)

non compos (p. 103)

non compos mentis – Latin: not of sound mind. A legal term, meaning that a person is not considered competent to transact legal business on his own behalf. [MH]

gold in them thar hills (p. 104)

From the California and Alaska Gold Rush days of the 1840s and 1890s. [NTPM]

up the river (p. 104)

Returning to the analogies of Blandings Castle to a prison; Ossining (Sing Sing) is about 30 miles up the Hudson River from New York City.

penitentiary (p. 105)

More prison comparisons.

give her a thingummy, and she’ll take a what’s-its-name (p. 106)

See Right Ho, Jeeves.

hoosegow (p. 106)

See Cocktail Time.

trunk call (p. 106)

A long-distance telephone call, from trunk line, a telephone line connecting two distant exchanges. [DS]

pippin (p. 106)

And so say all of us. (p. 106)

A traditional response to a toast or blessing, as in one of the later verses of “For he’s a jolly good fellow.”

he got my cousin, Ronnie Fish, married to a chorus girl (p. 106)

The story is related in the novels Summer Lightning/Fish Preferred (1929) and Heavy Weather (1933).

phalanx of aunts (p. 107)

Since Lord Emsworth has ten sisters, Ronnie has a mother (Lady Julia Fish) and nine aunts. The allusion is to ancient Greek history, a close-order array of soldiers with shields touching and spears overlapping; figuratively, to a number of persons closely allied for a common goal.

practically no limits to the powers of this wonder man (p. 107)

As similar phrases occur elsewhere in Wodehouse, describing a variety of characters, this may be a quotation from some popular film series, radio drama, comic book, or the like. Let me [NM] know if you can find the source.

“Are there no limits, I ask myself, to the powers of this wonder man?”

Lord Ickenham speaking of himself in Uncle Fred in the Springtime, ch. 16 (1939)

“Are there no limits to the powers of this wonder man?”

Terry Cobbold, speaking to and of Mike Cardinal, in Spring Fever, ch. 7 (1948)

There seemed no limits to the powers of this wonder man.

Agnes Flack, thinking of Captain Jack Fosdyke in “Feet of Clay” (in Nothing Serious, 1950)

“Are there no limits to the powers of this wonder man?”

Lady Monica Carmoyle, speaking of Jeeves in Ring for Jeeves/The Return of Jeeves (1953/54)

McAllister (p. 108)

Lord Emsworth’s head gardener, a dour Scotsman, is first met in Leave It to Psmith (1923).

fiver (p. 108)

A five-pound note; the rough equivalent of £150 in modern terms.

minor prophet (p. 108)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

scullion (p. 108)

An archaic term for a servant of the lowest rank, especially one who does the dirty work in the kitchen and the like.

a couple of bob (p. 108)

That is, two shillings, one-tenth of a pound sterling, the rough equivalent of £3 or US$4 in modern values.

Chapter Six

Runs from p. 110 to p. 148 in the 1947 Doubleday edition.

“Tchah!” (p. 110)

This interjection of “impatience or contempt” [OED] is an alternate spelling of “Pshaw!”

Nature has framed strange fellows in her time (p. 110)

From The Merchant of Venice; see Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse for the full passage and other references to it.

fungus (p. 110)

Facial hair; see Right Ho, Jeeves.

son of the soil (p. 110)

A farmer or agricultural worker; see Very Good, Jeeves.

heart is bowed down with weight of woe (p. 111)

See Sam the Sudden.

ewe lamb (p. 111)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

Young Lochinvar (p. 111)

See Right Ho, Jeeves.

damned cheek (p. 113)

The girl in Shakespeare is Viola from Twelfth Night; see Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse, and the original ends in “damask cheek” (see Thank You, Jeeves). Colonel Wedge substitutes a phrase more common in his soldierly lingo: “damned cheek” means roughly “blasted impertinence.”

Archimedes … Eureka (p. 113)

nothing but barley water (p. 113)

A soothing drink prepared by steeping pearl barley in boiling water, straining, and cooling, often with lemon and/or sugar to taste. Frequently mentioned in Wodehouse, along with lemonade, as alternative drinks for those who must avoid alcohol; not, however, regarded as sufficiently strengthening for those who are about to propose marriage.

Bingo’s voice was vibrant with scorn. “What on earth’s the good of barley water? How can you expect to be the masterful wooer on stuff like that?”

“Stylish Stouts” (in Plum Pie, 1966/67)

stately homes … Hemans (p. 115)

See Heavy Weather.

found himself [not] in complete sympathy (p. 115)

The US first edition omits the word ‘not’ here, but the UK reading makes much more sense in context.

A Wash-Out (p. 116)

A Squirt (p. 116)

Originally American slang from the nineteenth century, in Britain by the late nineteenth century, for a child or young person, or used disparagingly for a small or weak person.

some prophet of Israel (p. 116)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

King Arthur … Guinevere (p. 116)

See The Luck of the Bodkins. (Only the first paragraph of the comment there is relevant here, along with the cited passage from Tennyson.)

vultures gnawing at his bosom (p. 116–17)

nun (p. 118)

This seems to be the only mention of nuns in Wodehouse’s fiction, as far as can be found. Wodehouse of course was raised in the Church of England, and allusions like this seem somewhat out of place in his works. Perhaps he may have been influenced by Phoebe in Gilbert & Sullivan’s The Yeomen of the Guard:

Before I pretend to be sister to anybody again, I’ll turn nun, and be sister to everybody—one as much as another!

snip (p. 119)

See Summer Lightning.

Today’s Safety Bet (p. 119)

A sure thing; something headlined as worth betting on with little risk, as in a racecourse-handicapping column:

“I hope you chose something safe.”

“It ought to have been. The Sporting Express called it Today’s Safety Bet. It was Bounding Willie for the 2:30 race at Sandown last Wednesday.”

Leave It to Psmith, ch. 2.2 (1923)

ministering angel (p. 120)

See Laughing Gas.

grab her and kiss her a good deal and say, “My woman” (p. 120)

A forerunner of the Ickenham System of wooing, introduced the following year:

“Ignoring her struggles, clasp her to your bosom and shower kisses on her upturned face. You needn’t say much. Just ‘My mate!’ or something of that sort. Well, think it over, my dear fellow. But I can assure you that this method will bring home the bacon. It is known as the Ickenham System, and it never fails.”

Uncle Dynamite, ch. 11.2 (1948)

See also Cocktail Time.

continuity (p. 121)

Wodehouse is remembering his screenwriting days here; a continuity is an in-depth description of the action of a film, more detailed than a scenario. In fact, in the silent-film era, the continuity was the working script from which the film was directed, the whole set of “stage directions” for the action. In the talkie era, adding dialogue to the continuity resulted in the shooting script.

turned in its union card (p. 122)

The idea of phantom faces belonging to a labor organization is ludicrous enough on its own. Compare this with the spectral organization that assigns ghosts to haunt individual sites in Wodehouse’s early series of ghost stories, “Mr. Punch’s Spectral Analyses” (1903–04), such as “An Official Muddle” and others in the series.

phonus-bolonus (p. 123)

Originally American slang, apparently a noun variant of “phoney-baloney” meaning fraudulent or fake. Wodehouse uses it here to mean “funny business,” unfaithfulness, or insincerity, but it can also mean nonsense or foolishness.

“It was just a bit of phonus-bolonus. I was stringing you along so’s I could get hold of that notebook.”

Laughing Gas, ch. 18 (1936)

There had been a time, Mrs Steptoe frankly confessed, when the machinations of the man Weatherby had perplexed her. She had guessed, of course, that he was up to some kind of phonus-bolonus, but if you had asked her what particular kind of phonus-bolonus she would not have been able to tell you.

Quick Service, ch. 19 (1940)

I mean to say, it was perfectly obvious to the meanest intelligence that it was owing to some phonus-bolonus on his part that the conflagration had been unleashed, and I was conscious of a strong disposition to leave well alone.

Joy in the Morning, ch. 10 (1946)

His Nibs (p. 123)

A slangy way of referring to an aristocrat.

Florence Nightingale (p. 123)

See The Girl in Blue.

mot juste (p. 124)

See Right Ho, Jeeves.

“My mate!” (p. 124)

Lord Ickenham, conversely, preferred this form of address in the Ickenham System as quoted a few notes above, p. 120.

shaken hands with Tipton … member of the lodge (p. 124)

Diego Seguí notes that this is a clear reference to the masonic handshake. Wodehouse himself was a Mason, joining in 1929 and resigning in 1934.

quick service (p. 125)

Another of the do-it-now phrases from American business hustle that Wodehouse enjoyed quoting, and even used as the title of a 1940 novel.

gone on the pension list (p. 125)

That is, retired from active duty.

he could cut it (p. 127)

In other words, pretend he did not see the face. In etiquette, one of the strongest socially acceptable ways of indicating disapproval of another person is to “cut” them: to act as though you haven’t noticed that they are present.

Melancholy was marking her for its own (p. 127)

See A Damsel in Distress.

talk turkey (p. 127)

See Right Ho, Jeeves.

News of the World (p. 128)

A popular British Sunday newspaper, published from 1843 to 2011, which derived its high circulation from its emphasis on crime, vice, and populist sensation. By 1939, sales had reached four million copies each week.

blond/blonde whippet (p. 129)

A whippet is a small dog used for racing and hunting, typically a cross between a greyhound and a terrier or spaniel. The UK edition has “blonde” here, using the feminine form from French with the final -e; the US first edition has “blond” instead, which the OED says is now commonly used in North America in referring to both sexes.

“Ah, that du zurely be zo, m’lord,” (p. 130)

Bill is adopting a West Country English accent here, in which initial ‘s’ sounds are voiced, sounding like ‘z.’ Wodehouse may have been influenced by W. S. Gilbert’s libretto for The Sorcerer, in which the chorus lyrics in Act II are spelled to indicate a similar accent, with lines like:

If you’ll marry me, I’ll take you in and du for you!

All this will I du, if you’ll marry me!

a couple of bob (p. 131)

See p. 108, above.

his heart leaped up as if he had beheld a rainbow in the sky (p. 131)

See Summer Moonshine.

half a crown (half-a-crown) (later half-crown/half crown) (p. 131)

See Summer Lightning.

compact of sweetness and light (p. 131)

Wodehouse had used similar wording for Pop Stoker in Thank You, Jeeves, ch. 20 (1934):

Left to himself, this Stoker in about another half-minute would have been dancing round the room, strewing roses out of his hat. He was within a short jump of becoming a thing compact entirely of sweetness and light.

These are the only times that Wodehouse uses “compact” in the sense of “composed,” as Shakespeare does in A Midsummer Night’s Dream when Theseus says that “the lunatic, the lover, and the poet are of imagination all compact.”

For sweetness and light see Sam the Sudden, and be sure to follow the further link there.

reachmedowns. Pure Fifty-shilling Tailor (p. 134)

The UK first edition has reach-me-downs here. The reference is to ready-made suits, bought “off the rack” from a salesman who would reach up to get the suit down. Fifty shillings equal two and a half pounds; to account for inflation since 1947, the rough modern equivalent would be £75. No doubt Lord Emsworth had spent considerably more than that for his suits; Freddie is clearly being sarcastic here.

The OED notes that the term is also broadened to include clothes originally worn by someone else, especially an older family member; the equivalent would be “hand-me-downs” in American terms. See Uncle Dynamite.

get back to the res (p. 136)

Legal Latin for “the point at issue.”

A.W.O.L. (p. 138)

Absent Without Leave, a military infraction. The inference is that Freddie reacted with an open-eyed stare which caused his monocle to come loose.

floater (p. 138)

putting the kibosh on (p. 139)

See Ukridge.

qua (p. 139)

The UK first edition italicizes this Latin adverb, meaning “as; as being; in the capacity of.” So the phrase here means “—considered as rustic benches in themselves—” or something like that.

Her story being done, he gave her for her pains a world of sighs: he swore, in faith, ’twas strange, ’twas passing strange; ’twas pitiful, ’twas wondrous pitiful (p. 140)

From Othello; see Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse, and note that Wodehouse reverses the genders of the pronouns from Shakespeare’s original.

stuffed eelskin (p. 140)

Senior Conservative Club (p. 141)

See Something Fresh.

chauffeur … willingness to hear all (p. 141)

Compare:

Voules, the chauffeur, had had to fall back upon this secondary and inferior car; and anybody who has ever owned an Antelope is aware that there is no glass partition inside it shutting off the driver from the cash customers. He is right there in their midst, ready and eager to hear everything that is said and to hand it on in due course to the Servants’ Hall.

. . .