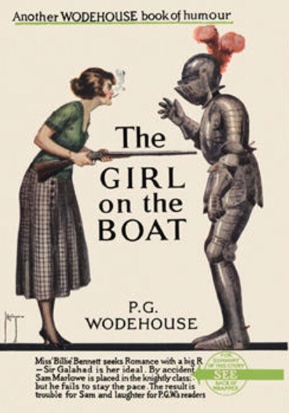

The Girl on the Boat

(Three Men and a Maid)

by

P. G. Wodehouse

Literary and Cultural References

This is part of an ongoing effort by the members of the Blandings Yahoo! Group to document references, allusions, quotations, etc. in the works of P. G. Wodehouse.

The Girl on the Boat was originally annotated by Mark Hodson (aka The Efficient Baxter). The notes have been reformatted, edited, and substantially extended by Neil Midkiff and others as credited below, but credit goes to Mark for his original efforts, even while we bear the blame for errors of fact or interpretation.

Page references and chapter titles in these notes are based on the Herbert Jenkins editions of the 1920s and 1930s, in which the text runs from page 11 to page 312. The US edition has no chapter titles.

A correspondence table showing the varying episode and chapter divisions and the pagination of several editions of the book is on this site (opens in a new window or browser tab).

Notes added in 2021 are flagged with *; substantially revised notes are flagged with °.

|

Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 Chapter 6 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 9 |

Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Chapter 12 Chapter 13 Chapter 14 Chapter 15 Chapter 16 Chapter 17 |

Notes

The story appeared in magazines under the title Three Men and a Maid, in the UK Pan from February to September 1921, and in shortened form in the US Woman’s Home Companion from October to December 1921. The Pan serial has a few passages which do not appear in either of the hardcover editions, and our transcription (linked above) is color-coded to show these.

The story appeared in magazines under the title Three Men and a Maid, in the UK Pan from February to September 1921, and in shortened form in the US Woman’s Home Companion from October to December 1921. The Pan serial has a few passages which do not appear in either of the hardcover editions, and our transcription (linked above) is color-coded to show these.

These notes are principally based on the UK book edition; only the more significant variants are noted here. The US edition is available as an etext from Project Gutenberg.

A film of the story was made in 1962 by Henry Kaplan. Slightly implausibly, it starred the comedian Norman Wisdom as Sam, together with British stalwarts Bernard Cribbins, Millicent Martin, Sheila Hancock, and Richard Briers.

Preface (p. v)

This Preface, titled “One Moment!”, does not appear in the US edition.

Herbert Jenkins (p. v)

Herbert Jenkins Limited published all Wodehouse’s books in the UK, from Piccadilly Jim (1918) onwards. The founder of the firm, Herbert Jenkins (1876–1923), moonlighted as an author, writing the Malcolm Sage detective stories and the Bindle comic novels as well as one or two serious books like a biography of George Borrow.

Pelham the Pincher (p. v)

A rare example of Wodehouse using one of his Christian names!

J. Storer Clouston’s The Lunatic at Large Again (p. v)

Joseph Storer Clouston (1870–1944), Scottish writer. The comic novel The Lunatic at Large (1893) seems to have been his best known work, and has been reprinted as recently as 1974 — The Lunatic at Large Again is presumably a sequel. Another book featuring some of the same characters, Count Bunker, is also available as a Project Gutenberg text.

at these cross-roads … no dirty work (p. vi) *

Constitutional Club, Northumberland Avenue (p. vi)

Norman Murphy (In Search of Blandings, 1986) makes a good case for identifying this club as the prototype of the Senior Conservative, which appears in many books from Psmith in the City onwards. This is the only place in the canon where it is mentioned by its real name, although there is plenty of evidence in other books to link the real and fictitious clubs.

Chapter 1 (pp. 11 – 26)

A Disturbing Morning

Mrs. Horace Hignett (p. 11)

Mrs. Hignett and her son are the only characters of this name in the canon.

Hignett may originally have been a Cheshire name. It could possibly be a reference to the British actor H. R. Hignett (1870–1959), who was prominent on the London stage before the First World War.

Dutch clock (p. 11)

The Zaan region north of Amsterdam is famous for clockmaking. Traditional Dutch clocks are usually weight-driven bracket clocks, often with a ceramic tile face.

ormolu clock (p. 11)

Ormolu (French: or moulu) is a material such as bronze or copper alloy covered with gold leaf. It was used especially in French furniture and clocks of the eighteenth century.

carriage clock (p. 11)

A spring-driven clock in a case with a handle, originally intended to be transportable.

Theosophy (p. 11)

A mystical philosophical system that takes the existence of God as its starting point, and seeks to deal with the presence of evil in the world. The Theosophical Society was founded by Mme. Blavatsky in 1875, although many of the ideas involved go back to Jakob Boehme and beyond.

Wodehouse’s brother Armine was a theosophist, and became head of the theosophical college at Benares, India.

Mrs. Hignett may be based loosely on the socialist and theosophist Annie Besant (1847–1933), who was Armine’s mentor in Benares.

http://www.theosophy.org/index.htm

About this time... (p. 12)

The US edition reads “The year 1921, it will be remembered, was a trying one for the inhabitants of the United States.” Presumably Herbert Jenkins advised against pinning the story to a specific date like this.

one of those great race movements (p. 12) *

“It’s like one of those great race movements you read about.”

Joy in the Morning, ch. 6 (1946)

“We don’t want the thing to look like one of those great race movements.”

Uncle Dynamite, ch. 9.2 (1948)

The exodus from the East, which had begun with the coming of sound to the motion pictures, was at its height. Already on the train the two had met a number of authors, composers, directors and other Broadway fauna with whom they had worked in the days before the big crash. Rudolf Friml was there and Vincent Youmans and Arthur Richman and a dozen more. It was like one of those great race movements of the middle ages.

Bring On the Girls, ch. 17.1 (1953)

This was in the ’twenties, when the flower of American youth was migrating to Paris in a manner reminiscent of the great race movements of the Middle Ages and all young men and women with souls and even the remotest ability to handle pen or paint brush went flocking to answer the call of the rive gauche.

French Leave, ch. 3 (1956)

“Odd how all these pillars of the home seem to be dashing away on toots these days. It’s like what Jeeves was telling me about the great race movements of the Middle Ages.”

Jeeves in the Offing, ch. 1 (1960)

With the result that the migration to Hollywood has been like one of those great race movements of the Middle Ages.

Letter to Bill Townend, June 26, 1930, in Author! Author! (1962)

“It’s like one of those great race movements of the Middle Ages I used to read about at school.”

Much Obliged, Jeeves, ch. 16 (1971)

Windles ... Hampshire (p. 12)

Many of the stately homes in Wodehouse, apart from Blandings Castle, are in Hampshire, where Wodehouse lived for some years before going to America.

The name Windles could perhaps be an allusion to The Vyne (home of the Sandys and later Chute families, near Basingtoke) or Broadlands (Lord Palmerston, the Mountbattens) — both of these more-or-less meet the description in the text, as would any number of other country houses in the area.

Windles was as the breath of life to her. (p. 13) *

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

did but hold it in trust for her son (p. 13)

Mrs. Hignett is obviously a widow. It was usual in English gentry families for the eldest son to inherit the house and estate, so that the family property would not be split up. Eustace would normally have come into full control of his inheritance on his 21st birthday, so we can assume that his mother’s trusteeship is a moral, rather than legal arrangement.

imitation coffee (p. 13) *

Health reformers in the late nineteenth century deprecated caffeine as a poison, and created substitute beverages; one of the first and most popular was Postum, created by C. W. Post in 1895, made from roasted grains and molasses.

What passed for brain in him was to genuine grey matter what just-as-good imitation coffee is to real Mocha.

The Intrusion of Jimmy/A Gentleman of Leisure, ch. 23 (1910)

Her day always began with a light but nutritious breakfast, at which a peculiarly uninviting cereal, which looked and tasted like an old straw hat that had been run through a meat chopper, competed for first place in the dislike of her husband and son with a more than usually offensive brand of imitation coffee. Mr. McCall was inclined to think that he loathed the imitation coffee rather more than the cereal, but Washington held strong views on the latter’s superior ghastliness.

“Washy Makes His Presence Felt” (1920; as ch. 22 of Indiscretions of Archie, 1921)

Wodehouse was given imitation coffee as a wartime internee, as recounted in “Huy Day by Day” in Performing Flea (1953).

Sir Mallaby Marlowe (p. 14) °

Mallaby is a moderately common surname, but there doesn’t seem to be any obvious Wodehouse link. The only other Mallaby in the canon is Clarice, the young lady with a craving for strawberries (“The Knightly Quest of Mervyn” in Mulliner Nights, 1933).

Marlowe is of course the name of the great Elizabethan playwright (and a town on the Thames). Besides Sir Mallaby’s son Sam, the only other Marlowes listed in Who’s Who in Wodehouse are George and Grace Marlowe in “Parted Ways” and Peggy Marlowe, a chorus girl in Barmy in Wonderland.

Wodehouse’s near-contemporary at Dulwich, Raymond Chandler, also seems to have been fond of the name Marlowe.

about thirteen stone (p. 15) *

About 182 pounds, or about 82.5 kilograms.

a cat in a strange alley (p. 15) *

See Uncle Fred in the Springtime.

Aunt Adeline (p. 15)

The name Adeline seems to have become popular in English through Mrs. Radcliffe’s gothic novel The Romance of the Forest (1791). Just possibly, Wodehouse is having a little dig at Virginia Woolf, whose middle name was Adeline.

put off childish things (p. 15) *

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

swallowed some drug which had caused him to swell unpleasantly, particularly about the hands and feet (p. 15) *

Wodehouse himself apparently had this feeling in embarrassing situations:

…those who, like myself, get elephantiasis in the hands and feet and can do nothing but gargle when called upon to utter three words in public…

“The Season-End Productions” (1920)

Several of his fictional characters have the same sensation:

But no hands and feet outside of a freak museum could have been one half as large as his seemed to be in the earlier days of his acquaintanceship with Keggs.

“Love Me, Love My Dog” (1910)

…the sensation of being a strange, jointless creature with abnormally large hands and feet…

“The Man With Two Left Feet” (1916)

Some kind of elephantiasis seemed to have attacked his hands and feet, swelling them to enormous proportions.

A Damsel in Distress, ch. 1 (1919)

…once more was afflicted by that curious sensation of having swelled in a very loathsome manner about the hands and feet.

Corky Corcoran, in “Buttercup Day” (1925)

…the sense of being an alien in a community where everybody seemed extraordinarily intimate with everybody else had weighed upon [Pilbeam], inducing red ears and a general sensation of elephantiasis about the hands and feet.

Heavy Weather, ch. 6 (1933)

[Bill Lister] had tottered out feeling that his hands and feet had been affected by some sort of elephantiasis and that his outer appearance was that of a tramp cyclist.

Full Moon, ch. 3.2 (1947)

[Myrtle Shoesmith Prosser gave Freddie Widgeon] an uncomfortable feeling in the pit of the stomach and the illusion that his hands and feet had swelled unpleasantly.

Ice in the Bedroom, ch. 2 (1961)

It made [Sam Bagshott] feel as if his hands and feet had swollen in a rather offensive manner and that his clothes had ceased to fit him.

Galahad at Blandings, ch. 8.2 (1965)

thews and sinews (p. 17)

Muscular strength. ‘Thews’ by itself used to mean the physical strength of a person, and was used in that sense by Shakespeare: Laertes in Hamlet; Falstaff in King Henry IV, part II; Cassius in Julius Caesar.

‘That villain’, exclaimed the Dwarf, ‘that coldblooded, hardened, unrelenting ruffian, that wretch, whose every thought is infected with crimes, has thews and sinews, limbs, strength, and activity enough, to compel a nobler animal than himself to carry him to the place where he is to perpetrate his wickedness.

: The Black Dwarf chap 6 (1816)

Washouts (p. 17) *

Failures; those who do not pass to a higher grade or rank in school or the military. See also The Inimitable Jeeves.

gas globes (p. 17)

The use of gas for lighting was still fairly common in Britain, even long after the invention of incandescent electric lights around 1900. Some installations survived until the introduction of natural gas in the early 1970s. A globe is a protective glass or mesh bowl surrounding the incandescent ceramic mantle.

Frank Tinney (p. 17)

American comedian and singer — like Al Jolson, he was best known for performing in black make-up.

Trinity smoker (p. 17)

Trinity is one of the smaller, quieter colleges of Oxford University, founded in 1555 by local businessman Sir Thomas Pope. Famous members have included the explorer Sir Richard Burton. Nowadays it is best known for sitting on top of the underground parts of Blackwell’s bookshop and the Bodleian.

A smoker, or smoking concert, was a private entertainment put on by the members of a club or similar institution (men only, hence smoking was allowed). Usually, the performers would be the members of the club itself. See Not George Washington for an account of the Barrel Club smoker.

come down from Oxford (p. 18)

Left the university, graduated. Undergraduates are said to be “up” at Oxford or Cambridge while in residence as members of a college. To be “sent down,” by contrast, is to be expelled from the university.

the Atlantic (p. 18) °

Presumably fictitious. The White Star line, which lost its independent identity in 1935, used names ending in ‘-ic’ for its postwar ships (Britannic, Majestic, etc.). The Atlantic also appears in “Life with Freddie”, Piccadilly Jim, Leave It to Psmith and The Luck of the Bodkins.

See Piccadilly Jim.

Mr. Bennett ... Mr. Mortimer (p. 19) °

The only other Bennetts in the canon appear in the story “Crowned Heads” (1915).

There are a few other minor characters with the surname Mortimer, not to mention the art critic Mortimer Bayliss in Something Fishy and the golfer Mortimer Sturgis in “Sundered Hearts” (1920) and “A Mixed Threesome” (1921).

Just possibly, Wodehouse might have been thinking of that archetype of long-suffering fathers of willful daughters, Jane Austen’s Mr. Bennett in Pride and Prejudice.

gassing away (p. 20) *

That is, speaking, especially at length or foolishly. The British still use “gas” as Americans use “hot air” in this sense; both are used to fill balloons.

Erin (p. 20)

Poetic name for Ireland

Bream Mortimer (p. 20)

A bream is a freshwater fish, although the word does appear occasionally as a surname.

cold fury (p. 20) *

Most of us would tend to think of fury as a hot emotion rather than a cold one, but “cold fury” begins to show up in literature about 1870. Wodehouse seems first to have used it in Uneasy Money, ch. 19 (1916):

A feeling of cold fury surged over her at the way Fate had tricked her.

looked … like a parrot (p. 21) *

Others who resemble parrots are Boko Fittleworth (Joy in the Morning, 1946) and Erbut/Herbert who has a cold grey eye like a parrot’s in “All’s Well With Bingo” (1937).

Little Church Round the Corner (p. 22)

The Church of the Transfiguration, off Madison Square on East 29th Street, where Wodehouse married Ethel on 30 September 1914. The song “The Church Round the Corner” featured in the Wodehouse/Bolton/Kern show Sally (1920).

The church was founded in 1848 by the Rev. G. H. Houghton, an American Episcopal follower of the ideas of Pusey, Keble, and Newman, the leaders of the Anglo-Catholic “Oxford Movement,” in the Church of England.

In the late 19th century it started to be seen as the Broadway actors’ church, a role it retains today.

psycho-analysis (p. 23) *

This term for Freud’s therapeutic method for treating mental disorders was rarely used before 1920 outside of medical journals and textbooks, so it had only recently entered popular culture at the time of this writing. Mrs. Hignett is using it loosely rather than technically here, of course.

vibrate on the same plane (p. 24) *

Originally a term in physics, referring to mechanical oscillations which can be coupled or resonated from one body to another because of having freedom of movement in the same direction. The earliest reference so far found that figuratively applies this to two persons is from John Uri Lloyd in 1878; by the early twentieth century the term began to be used in popular literature for psychological or romantic affinity.

auras are not the same colour (p. 24) *

Those of us who first heard similar terms in the 1960s and 1970s may be surprised to see this reference in a 1922 book, but this was nothing new even then. A quick search has found references to colored auras as far back as 1871, in the Phrenological Journal.

spilled the beans (p. 25) *

Told a secret. US slang which was fairly fresh at the time; the OED has citations beginning in 1919.

threw a spanner into the machinery (p. 25) *

See Leave It to Psmith.

crabbed his act (p. 25) *

Slang for interfering with his plans, obstructing his success. The earliest OED citation for “crab my act” is from Carl Sandburg in 1922.

gummed the game (p. 25) *

The first OED citation for this phrase is in a sporting context, using tactics to delay a game. In a figurative sense, for spoiling someone’s plans, the first citation is from Wodehouse, quoted from Their Mutual Child in 1919, which first appeared in 1914 in a magazine as The White Hope, ch. 5 (1914):

“It would sure get my goat the worst way to have the old man gum the game for them.”

celebrated chewing-gum. The taste lingered. (p. 26) *

See Right Ho, Jeeves.

Chapter 2 (pp. 27 – 55)

Gallant Rescue by Well-dressed Young

Man

Rivington Street (p. 28)

Formerly a slum area, on the fringes of the Bowery and Greenwich Village.

being seen off by detectives (p. 28)

Cf. Ukridge’s departure from Canada (“Ukridge Sees Her Through”).

his heart had been lying empty, all swept and garnished (p. 29) *

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

honking their wares (p. 30) *

An unusual use of this verb, and the first use of this phrase found in the Google Books corpus; the more typical term for selling items outdoors with loud cries is “hawking” as in “The Book-Hawkers” (1906).

companion-way (p. 31)

On a ship, a companion-way is a ladder or staircase leading from one deck to another.

vers-libre (p. 32)

Free verse: poetry that does not have a fixed rhythmic pattern or rhyme-scheme. T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, probably the most famous free-verse poem in English, was published the same year as The Girl on the Boat.

J. B. Midgeley (p. 33)

Seems to be the only Midgeley in the canon. The surname, in various spellings, is quite common, especially in Yorkshire and County Durham. There are two villages in Yorkshire called Midgley.

scratched the fixture (p. 35) *

bags (p. 35) *

British slang from mid-nineteenth century for trousers, especially loose-fitting ones.

Thomas Otway .. ‘Orphan’ (p. 37)

Happy a while in Paradise they lay;

But quickly woman longed to go astray:

Some foolish new adventure needs must prove,

And the first devil she saw, she chang’d her love:

To his temptations, lewdly she inclined

Her soul, and, for an apple, damn’d mankind.

[...]

What mighty ills have not been done by woman!

Who was ’t betrayed the Capitol?—A woman!

Who lost Mark Antony the world?—A woman!

Who was the cause of a long ten years’ war,

And laid at last old Troy in ashes?—Woman!

Destructive, damnable, deceitful woman!

: The Orphan Act III

bar ... three-mile limit (p. 37)

The Volstead Act, enforcing the 18th Amendment and thus prohibiting the sale of alcoholic beverages, came into force — over President Wilson’s veto — in 1919. The 18th Amendment was repealed in 1933. The three-mile limit refers to the extent of a nation’s jurisdiction over international waters; once the boat is three miles from shore, Prohibition no longer is enforceable.

ray of sunshine (p. 38) *

See Bill the Conqueror.

mauve pyjamas (p. 38) *

See Uncle Fred in the Springtime.

sheep … separating from the goats (p. 38) *

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

excitement toward (p. 38) *

See Leave It to Psmith.

the work of a moment (p. 39) *

See A Damsel in Distress.

between sea and sky (p. 40) *

My sports were lonely, ’mid continuous roars,

And craggy isles, and sea-mew’s plaintive cry

Plaining discrepant between sea and sky.

Keats: Endymion, III:340–42 (1818)

leap from crag to crag like the chamois of the Alps (p. 40) *

See Sam the Sudden.

Oscar Swenson (p. 41)

Seems to be a generic Swedish name.

Svensk! (p. 42)

Svensk is of course the Swedish word for “Swedish.”

He travels … the fastest who travels alone (p. 42) *

From Kipling’s “The Winners” (1888).

scows, skiffs, launches,... (p. 45)

In this context, a scow is a flat-bottomed workboat like a large punt; a skiff is a light rowing boat, and a launch is a small motor boat.

North River (p. 45) °

An alternative name for the portion of the Hudson River between New Jersey and Manhattan Island.

The White Star Line used Pier 59, opposite West 17th Street. It is now part of the Chelsea Piers sports complex.

Reuben S. Watson (p. 46)

Tugs are often named after family members of the owners.

The only remotely celebrated Reuben Watson seems to have been the founder of R. Watson and Sons, which is now the British arm of the actuaries Watson Wyatt.

Or perhaps this is a buried Sherlock Holmes reference??

following a famous precedent (p. 46) *

It was the schooner Hesperus

That sailed the wintry sea;

And the skipper had taken his little daughter

To bear him company.

Longfellow: “The Wreck of the Hesperus” (1842).

played … like a public fountain (p. 46) *

A dripping figure rose violently in the stern of the boat, spouting water like a public fountain.

“Rodney Fails to Qualify” (1924)

He was in the middle of the Octagon, seated on the roof and spouting water like a public fountain.

“Jeeves and the Impending Doom” (1926; in Very Good, Jeeves, 1930)

Monty nodded, scattering water like a public fountain.

Heavy Weather, ch. 9 (1933)

“You sure are wet!” (p. 47) *

The reactions of those who see Sam’s dripping condition on this and the next few pages are reminiscent of other passages in Wodehouse where spectators can say only the most obvious observations.

“She says to me, ‘Why, whatever ’ave you been a-doing? You’re all wet.’ ”

Constable Butt in Jackson, Junior, ch. 9 (1907; later as the first half of Mike, 1909)

Of the fifteen who got within speaking distance of him, six told him that he was wet.

“Deep Waters” (1910)

“How wet you are!”

Honoria Glossop to Bertie in “Scoring Off Jeeves” (1922)

“By Jove, you are wet!” said Ronnie.

To Monty Bodkin in Heavy Weather, ch. 9 (1933)

do a Brodie (p. 47)

Steve Brodie (1863–1901) was a Brooklyn bookmaker famous for jumping off the Brooklyn Bridge and surviving the fall, on July 23, 1886, although there are those who say that it was merely a publicity stunt using a dummy.

berries … seeds (p. 49) *

For berries see Leave It to Psmith. For seeds see Green’s Dictionary of Slang.

Chapter 3 (pp. 56 – 68)

Sam Paves the Way

the vampire of a five-reel feature film (p. 56) *

For vampire see Summer Lightning. In the days of silent film, with varying film speeds in camera and projector, the length of films was given in feet, or in round numbers in reels containing up to 1000 feet of 35mm film. A five-reel film in the early 1920s would last approximately one hour.

coming down to brass tacks (p. 57) *

Originally American colloquial phrase for being concerned with the basic facts of a situation; dealing in realities rather than speculation. OED has citations beginning in 1897. This appears to be Wodehouse’s first usage of the phrase.

realising this at the eleventh hour (p. 57) *

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

party of the second part (p. 58) *

Legal terminology, used in contracts and the like, to mean “the second person named above” or, informally, “the other person involved.”

dime museum (p. 58) *

A popular type of institution in late 19th-century America, designed to appeal to the masses at low admission prices. These combined exhibits of strange and wonderful items (some real, some faked) with stage presentations by magicians, circus performers and freaks, musicians, and actors, with an emphasis on the sensational and bizarre.

the counter-irritation principle (p. 59) *

In medicine, a strategy for lessening pain by applying a substance to the skin that creates a mild irritant stimulus to the nerves as a distraction from more fundamental causes of pain. Many “hot-and-cold” arthritis or muscle ache relief remedies based on capsaicin (pepper essence), menthol, methyl salicylate, and/or camphor create a not-too-unpleasant tingle in the skin that overloads the sensory nerves and interferes with pain sensations from the joints or muscles.

Three shillings and sixpence (p. 61) °

The equivalent of 17.5p in decimal currency. The Bank of England inflation calculator suggests a factor of 50 in consumer price inflation from 1921 to 2020, so this would be the rough equivalent of £8.75 or US$11 in modern terms.

Limerick (p. 61)

A short humourous nonsense verse form, it consists of five anapestic lines with the rhyme scheme aabba. The third and fourth lines have two stresses each, and the others three. It has been around in various guises since medieval times, but only achieved serious popularity with the publication of Edward Lear’s first Book of Nonsense in 1846. The association of the name “Limerick” with the form is not very clear — the OED asserts that it comes from an old parlour game where each person had to improvise a verse, which was followed by a chorus of “Will ye come to Limerick”.

There was a Young Lady whose chin

Resembled the point of a pin:

So she had it made sharp,

And purchased a harp,

And played several tunes with her chin.

: There was a young lady whose chin

sonnet-sequence (p. 61)

A few pages back Wodehouse accused Eustace of writing free verse, but here he is talking about writing in sonnet form, probably the strictest and most challenging form in English poetry.

pencil ... cuff (p. 61)

Many men at this time, especially from the working and middle classes, wore shirts with detachable, disposable cuffs and collars made out of paper or celluloid. Such cuffs were a convenient place to jot down notes. This practice is the origin of the phrase “off the cuff.”

Tennyson ... Idylls of the King (p. 61)

Tennyson published his main collection of retellings of the Arthurian legends in 1859. Although extremely popular at the time, and catering to the mid-Victorian taste for all things medieval, these blank-verse epics full of cringe-makingly stilted pseudo-archaic language don’t really show Tennyson at his best, and are not much read these days. They would certainly have been the courtship-literature of choice for the generation of Wodehouse’s parents, but don’t seem a very likely preference for a young woman in the early 1920s (or for a poet who writes free verse).

morocco (p. 62) *

A fine grade of leather made from tanned goatskin, very flexible, often used in bookbinding.

Chesterfield (p. 63) *

See Blandings Castle and Elsewhere.

intervene ... dog-fights (p. 64)

All of Wodehouse’s young men-of-action seem to share a talent for stopping dog-fights.

craven (p. 64) *

See Leave It to Psmith.

raisin dropped in the yeast (p. 65)

This doesn’t seem to be a quotation (?) — it seems to be a rather odd way of going about inducing fermentation. Normally one adds yeast to the mixture one wants to ferment, rather than the other way around.

big-game hunter (p. 66) *

Other female big-game hunters include Lady Bassett in “Strychnine in the Soup” (1932; in Mulliner Nights, 1933) and Clarissa Cork in Money in the Bank (1941).

Worcester Sauce (p. 66) *

See Carry On, Jeeves!.

The US magazine serial omits the references to this proprietary sauce, both here and in ch. 7.

botts (p. 66) *

See Summer Lightning.

Chapter 4 (pp. 69 – 94)

Sam Clicks

In slang of the time, to click is to succeed, to make a hit. (Cf. “The Clicking of Cuthbert”)

...when this story is done in the movies (p. 69) °

Wodehouse, of course, didn’t know that talking pictures would be well-established before this happened (see above).

“Everybody wants a key to my cellar” (p. 70)

A comic song by Bert Williams from the early days of Prohibition.

Everybody wants a key to my cellar …

I’d like to see them get one; let them try,

You can have my money,

Take my car,

Take my wife if you want to go that far.

But nix on a key to open my cellar

If the whole darned world goes dry!

: Everybody wants a key to my cellar (1919)

Recording of Bert Williams singing it, at YouTubethe man who has had a cold bath (p. 70) *

See A Damsel in Distress.

put his fortune to the test, to win or lose it all (p. 70)

A paraphrase of lines from My Dear and Only Love, by James Graham, Marquess of Montrose (1612–1650):

He either fears his fate too much,

Or his deserts are small,

That puts it not unto the touch

To win or lose it all.

Montrose’s “touch” is in the oldest sense meaning “test” as in checking the purity of gold with a touchstone. Wodehouse’s paraphrase is clearer for modern readers, and he uses it in full in “The Fatal Kink in Algernon” (1916) and “The Ordeal of Osbert Mulliner” (1928), and in abbreviated form in A Damsel in Distress, ch. 12 (1919).

Wodehouse paraphrases it differently elsewhere as “fate to the test”; see Money in the Bank. [NM]

pour-parlers (p. 71)

Preliminary discussions (Old French pourparler, to discuss). For more on Victorian courtship rituals, see Spring Fever, Ch.15.

feelings deeper than those of ordinary friendship (p. 71) *

For two different comments on this phrase, see Laughing Gas and Thank You, Jeeves.

Alphonso (p. 72)

Wodehouse also refers to these lines (without quoting them) in A Damsel in Distress, and Lord Uffenham slightly misquotes them in Something Fishy/The Butler Did It, ch. 13.

Alphonso, who in cool assurance all creation licks,

He up and said to Emmie (who had impudence for six),

‘Miss Emily, I love you—will you marry? Say the word!’

And Emily said, ‘Certainly, Alphonso, like a bird!’

: Bab Ballads: ‘The Modest Couple’

Bruton Street, Berkeley Square (p. 72)

A street in London’s Mayfair district, only a bun’s toss from the Drones Club in Dover Street. Runs from the NE corner of Berkeley Square across to Bond Street.

wind and weather permitting (p. 72) *

See Thank You, Jeeves.

“I am the Bandolero” (p. 73)

Song, 1894, words and music by Thomas Augustine Barrett (1863–1928), who had a career as a classical pianist and wrote popular songs under the pseudonym ‘Leslie Stuart.’ He was best known for the hit show Florodora (1899) and would have been one of the biggest names in British musical theatre in Wodehouse’s youth.

This song was later to be made famous by Albert Peasemarch (see The Luck of the Bodkins).

dresses that have to be hooked up... (p. 74)

This suggests a degree of intimacy that Eustace is unlikely to have reached with Miss Bennett: possibly his mother has made him hook up her dresses, or perhaps it is Wodehouse’s own experience of four years of marriage coming out?

miss in baulk (p. 75) *

An intentional avoidance; a term from English billiards. See Love Among the Chickens.

Romeo and Juliet ... pleasantness of the morning (p. 76)

Shakespeare makes it quite clear that the “balcony scene” (Act 2, Sc. 2) takes place at night, as Juliet is going to bed. Wodehouse is maybe thinking of Romeo’s famous opening lines comparing Juliet herself to the dawn.

But, soft! what light through yonder window breaks?

It is the east, and Juliet is the sun!

Arise, fair sun, and kill the envious moon,

Who is already sick and pale with grief,

That thou her maid art far more fair than she:

Be not her maid, since she is envious;

Her vestal livery is but sick and green,

And none but fools do wear it; cast it off.

It is my lady; O! it is my love:

O! that she knew she were.

: Romeo and Juliet II:ii, 4–12

See Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse for other references to the balcony scene.

[The US magazine and book versions titled Three Men and a Maid omit the entire paragraph referring to Shakespeare, Romeo, and Juliet.]

tube station (p. 77) °

London’s first deep-level electric “tube” railway, the City and South London, opened in 1890. [Earlier Underground lines had been excavated below the streets using a cut-and-cover system, and initially were powered by steam engines.] By 1921, the system in central London was essentially complete (the Victoria and Jubilee lines are the only major parts to have been added since then).

In the US magazine and book versions, the reference is instead to “practically Fifth Avenue and Forty-second Street”—a busy intersection in Manhattan.

turning his face to the wall (p. 78) *

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

The time and the place and the girl—they were all present and correct (p. 80) *

Alluding to a popular number from Victor Herbert’s 1905 operetta Mademoiselle Modiste, “The Time and the Place and the Girl” with lyrics by Henry Blossom:

For the time may be morning or evening;

The place may be distant or near;

And the maiden demure may have made you feel sure

That she’ll be there without any fear.

But there’s always a hitch in it somewhere,

And the thought sets your brain in a whirl;

For seldom, if ever, you find them together,

The time, and the place, and the girl.

“The Rosary” (p. 82)

Song (1898), music by Ethelbert Woodbridge Nevin (1862–1901). With a name Wodehouse would have been proud to invent, he was one of the most famous American composers of his day but now largely forgotten; the words are by the justly obscure Robert Cameron Rogers. The song was a huge success at the time.

It also appears in the story “Lines and Business” (1912) (a.k.a. “Fixing it for Freddie”).

The hours I spent with thee, dear heart,

Are as a string of pearls to me;

I count them over, every one apart,

My Rosary, my Rosary.

Each hour a pearl, each pearl a prayer,

To still a heart in absence wrung;

I tell each bead unto the end,

And there a cross is hung.

O memories that bless and burn!

O barren pain and bitter loss!

I kiss each bead, and strive at last to learn

To kiss the cross;

Sweetheart!— to kiss the cross.

: The Rosary

Oh let the solid ground... (p. 83)

Sam seems to have picked up the wrong book — this is from Maud, not The Idylls of the King.

Perhaps not the happiest of choices, when one considers that the speaker of Maud is well on the wrong side of the line separating romantic love from serious mental illness by the time he gets to this point in the poem.

O let the solid ground

Not fail beneath my feet

Before my life has found

What some have found so sweet!

Then let come what come may,

What matter if I go mad,

I shall have had my day.

Let the sweet heavens endure,

Not close and darken above me

Before I am quite quite sure

That there is one to love me!

Then let come what come may

To a life that has been so sad,

I shall have had my day.

: Maud Pt I, XI

It was like the gate of heaven opening. (p. 84) *

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

Walt Mason (p. 84)

Canadian-born poet and journalist (1862–1939), famous for his rhyming prose pieces, many of which appeared in the Detroit Free Press. Compare the piece below with the opening chapter of Ring for Jeeves or Hemingway’s “Short, Happy Life of Francis Macomber”...

Once a hunter met a lion near the hungry critter’s lair, and the way that lion mauled him was decidedly unfair; but the hunter never whimpered when the surgeons, with their thread, sewed up forty-seven gashes in his mutilated head; and he showed the scars in triumph, and they gave him pleasant fame, and he always blessed the lion that had camped upon his frame. Once that hunter, absent minded, sat upon a hill of ants, and about a million bit him, and you should have seen him dance! And he used up lots of language of a deep magenta tint, and apostrophized the insects in a style unfit to print. And it’s thus with worldly troubles; when the big ones come along, we serenely go to meet them, feeling valiant, bold and strong, but the weary little worries with their poisoned stings and smarts, put the lid upon our courage, make us gray, and break our hearts.

: Lions and Ants

the Princess and the Swineherd (p. 86) °

Title of a moral fable by Hans Christian Andersen. English translation from the Hans Christian Andersen Centre.

My love is like a glowing tulip... (p. 86)

Could well be an authentic Victorian ballad, but I haven’t been able to find any confirmation of this.

trying to hide your light under a bushel (p. 87) *

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

§4 (p. 88) °

Section 4 of Chapter IV is omitted in the US magazine and book editions, and a longer dialogue between Billie and Sam beginning “Suddenly, as he released her” and discussing Mr. Bennett and Bream Mortimer is inserted in its place. The magazine version of this inserted passage is very slightly abridged from the US book version.

The following notes refer to the UK edition of section 4.

Jane Hubbard (p. 88) °

One of Wodehouse’s most splendid women characters, and the only Hubbard in the canon. The other notable female elephant-gun exponents are the rather less attractive Mrs. Clarissa Cork in Money in the Bank and Lady Bassett in “Strychnine in the Soup.”

Jane’s first name must owe something to the heroine of Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Tarzan stories, which appeared as a magazine serial in 1912, a book in 1914 and on film for the first time in 1918. Of course, Wodehouse was not to know that the most celebrated movie Jane, Maureen O’Sullivan (still a schoolgirl in 1921), would later become a family friend of the Wodehouses and dedicatee of Hot Water.

sweetness and light (p. 89) *

See Uncle Fred in the Springtime.

Boadicea (p. 89) *

See Right Ho, Jeeves.

eighty-five times round the promenade deck (p. 89) *

We don’t know the length of the fictional Atlantic, but other White Star liners of the era can be used as stand-ins for estimation. The Britannic was 883 feet in length; the Olympic and Titanic were about the same. The present-day Rotterdam of the Holland America Line is 984 feet long, and its promenade deck measures 3.5 laps to the mile, so a guess of four or five laps to the mile for the Atlantic seems reasonable. Jane Hubbard has then walked somewhere between seventeen and twenty-one miles; no wonder she is “pleasantly tired”!

go into Parliament (p. 90)

A limited number of women (those who were over thirty and were graduates, householders, or the wives of householders) were given the vote in the UK by the Representation of the People Act 1918. Constance Markiewicz was the only woman to be elected in the 1918 general election, but was a Sinn Fein member who refused to take her seat, so the first woman in Parliament was the Conservative, Nancy Astor, who won her husband’s old seat in a by-election in 1919 when he inherited a peerage.

the pictures of Lord Byron (p. 91) *

A set of portraits of Byron can be seen at Wikimedia.

ships that pass in the night (p. 91) *

This image for a brief meeting between people (especially potential lovers) who do not expect to encounter each other again comes from a Longfellow poem:

Ships that pass in the night, and speak each other in passing,

Only a signal shown and a distant voice in the darkness;

So on the ocean of life we pass and speak one another,

Only a look and a voice, then darkness again and a silence.

“The Theologian’s Tale: Elizabeth” from Tales of a Wayside Inn (1863)

refusing your oats (p. 91) *

By humorous analogy to a horse who is disinclined to eat, meaning having lost one’s appetite.

British East Africa (p. 91)

This term was used between 1886 and 1920 for — broadly-speaking — the British protectorate covering the area of the modern countries Kenya and Uganda.

Unless she was actually there during hostilities (possibly disguised as Katherine Hepburn??), she must have been there in 1919, before the name was changed to Kenya.

Annie Laurie (p. 92)

Annie Laurie (1682–1764) was the daughter of Sir Robert Laurie of Maxwelton House, in Dumfriesshire (SW Scotland). It’s not recorded whether Douglas did lay him doon and dee when Annie married someone else. According to Brewer, her son, Alexander Ferguson, was in turn the hero of a Robert Burns song, “the Whistler”.

Max Welton’s braes are bonnie

Where early falls the dew

And ’twas there that Annie Laurie

Gave me her promise true.

Gave me her promise true

That ne’er forgot shall be

And for Bonnie Annie Laurie

I’d lay me doon and dee.

Her brow is like the snowdrift

Her nape is like the swan

And her face it is the fairest

That ’ere the sun shone on.

That ’ere the sun shone on

And dark blue is her E’e

And for Bonnie Annie Laurie

I’d lay me doon and dee.

Like the dew on the Gowan Lion

Is the fall of her fairy feet

And like winds in the summer sighing

Her voice is low and sweet.

Her voice is low and sweet

And she’s all the world to me

And for Bonnie Annie Laurie

I’d lay me doon and dee.

: Annie Laurie

the scales seemed to fall from my eyes (p. 93) *

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

I can’t forgive a man for looking ridiculous (p. 93) *

Billie Bennett in this respect is somewhat like other Wodehouse characters including Cora Bellinger, Lady Florence Craye, and Bertie’s Aunt Agatha; see the notes to Very Good, Jeeves for a discussion.

Chapter 5 (pp. 95 – 103)

Persecution of Eustace

father in the pigstye (p. 95) °

See Heavy Weather.

Note the rare spelling of pigstye with a final “-e” (a quick internet sample suggests that the other spelling is 65 times more common) – Wodehouse also spells it this way when he uses the same joke in Jill the Reckless.

burnt cork (p. 96)

A much safer way to black up than boot polish: cf. Thank You, Jeeves.

a different and a dreadful world (p. 96) *

See Very Good, Jeeves.

Titian (p. 98)

Veccelio Tiziano (1490–1576), known in the English-speaking world as Titian, is particularly known for painting women with the flowing red-blonde hair then fashionable in Venice. The work of Dante Gabriel Rossetti helped to revive the fashion for red hair in late-Victorian Britain.

Titian’s Flora (1515–20) in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence

toad beneath the harrow (p. 99)

The toad beneath the harrow knows

Exactly where each tooth-point goes;

The butterfly upon the road

Preaches contentment to that toad.

: Pagett, MP

registering of emotion (p. 101) *

See Right Ho, Jeeves.

bounders (p. 101) *

See Bill the Conqueror.

Schopenhauer (p. 101)

Arthur Schopenhauer (1788–1860), philosopher, author of The World as Will and Representation, was noted for his pessimism and misogyny.

Chapter 6 (pp. 104 – 110)

Scene at a Ship’s Concert

deep-sea fish ... haddocks ... shrimps (p. 104)

While there are some shrimps who live in deep water, they are crustaceans, not fish.

rival lady singers (p. 105)

For similar programme clashes, see The Luck of the Bodkins and “Jeeves and the Song of Songs”.

“Gunga Din” (p. 105)

’E carried me away

To where a dooli lay,

An’ a bullet come an’ drilled the beggar clean.

’E put me safe inside,

An’ just before ’e died,

“I ’ope you liked your drink”, sez Gunga Din.

So I’ll meet ’im later on

At the place where ’e is gone—

Where it’s always double drill and no canteen;

’E’ll be squattin’ on the coals

Givin’ drink to poor damned souls,

An’ I’ll get a swig in hell from Gunga Din!

Yes, Din! Din! Din!

You Lazarushian-leather Gunga Din!

Though I’ve belted you and flayed you,

By the livin’ Gawd that made you,

You’re a better man than I am, Gunga Din!

: Gunga Din (last stanza)

“Fuzzy-Wuzzy” (p. 105)

“Fuzzy-Wuzzy” is another of Kipling’s Barrack-room Ballads. Fuzzy-Wuzzy was the British soldiers’ name for their opponents in the Sudanese campaign.

So ’ere’s to you, Fuzzy-Wuzzy, at your ’ome in the Soudan;

You’re a pore benighted ’eathen but a first-class fightin’ man;

An’

’ere’s to you, Fuzzy-Wuzzy, with your ’ayrick ’ead of ’air—

You

big black boundin’ beggar—for you broke a British square!

: Fuzzy-Wuzzy (refrain)

My Little Gray Home in the West (p. 105)

When the golden sun sinks in the hills

And the toil of a long day is o’er

Though the road may be long, in the lilt of a song

I forget I was weary before.

Far ahead, where the blue shadows fall

I shall come to contentment and rest;

And the toils of the day will be all charmed away

In my little grey home of the west.

There are hands that will welcome me in

There are lips I am burning to kiss

There are two eyes that shine just because they are mine,

And a thousand things other men miss.

It's a corner of heaven itself

Though it’s only a tumble-down nest,

But with love brooding there, why no place can compare

With my little grey home in the west.

: Little Grey Home in the West (song, 1911)

The sheet music is online at the Ball State University library.

If anybody had told him then that five minutes later he would be placing himself of his own free will within range of a restaurant orchestra playing My Little Gray Home in the West—and the orchestra at the Regent played little else—he would not have believed him.

Piccadilly Jim, ch. 6 (1917)

All through the voyage he remained moody and distrait; and at the ship’s concert, at which he was forced to take the chair, he was heard to observe to the purser that if the alleged soprano, who had just sung My Little Gray Home in the West, had the immortal gall to take a second encore he hoped that she would trip over a high note and dislocate her neck.

“High Stakes” (1925; in The Heart of a Goof, 1926)

“You didn’t sing My Little Gray Home in the West at the ship’s concert?” he demanded, eying her closely.

“High Stakes” (1925)

fair women and brave men (p. 105)

There was a sound of revelry by night,

And Belgium’s capital had gather’d then

Her beauty and her chivalry, and bright

The lamps shone o’er fair women and brave men.

A thousand hearts beat happily; and when

Music arose with its voluptuous swell,

Soft eyes look’d love to eyes which spake again,

And all went merry as a marriage bell.

: Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage III:21

Keats ... knell (p. 105)

Wodehouse seems to have thought Keats wrote knell, not bell. He also uses this image in Money for Nothing, Ch.4.

... The same that oft-times hath

Charmed magic casements, opening on the foam

Of perilous seas, in faery lands forlorn.

VIII

Forlorn! the very word is like a bell

To toll me back back from thee to my sole self!

: Ode to a Nightingale 68-72

Macbeth at the ghost of Banquo (p. 108) °

In Shakespeare’s Macbeth, Act III, Scene iv, a dinner party is altogether ruined when the ghost of the murdered Banquo turns up uninvited and sits in Macbeth’s chair.

http://www.bartleby.com/46/4/34.html

See Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse for other references to this passage.

The Shakespeare reference is omitted in the US magazine serialization.

There was a rustle at Billie’s side (p. 109)

Thus in UK book; US magazine has “a rustle of taffeta” and US book has “a rustle of millinery” here.

Chapter 7 (pp. 111 – 125)

Sundered Hearts

Runs from pp 111 – 125 in the Herbert Jenkins edition.

When a man’s afraid... (p. 111)

The bard in question being W. S. Gilbert, of course — this is from the wonderful scene where Ko-Ko, Pooh-Bah and Pitti-Sing introduce a certain amount of corroborative detail, intended to give artistic verisimilitude to an otherwise bald and unconvincing narrative in describing the (wholly imaginary) execution of Nanki-Poo.

Pitti-Sing: He shivered and shook as he gave the sign

For the stroke he didn’t deserve;

When all of a sudden his eye met mine,

And it seemed to brace his nerve;

For he nodded his head and kissed his hand,

And he whistled an air, did he,

As the sabre true

Cut cleanly through

His cervical vertebrae, his vertebrae!

When a man’s afraid,

A beautiful maid

Is a cheering sight to see;

And it’s oh, I’m glad

That moment sad

Was soothed by sight of me!

: The Mikado, or The Town of Titipu Act II

You have to use butter (p. 113) *

As Bertie Wooster and Sir Roderick Glossop learn when removing their own black-face makeup (this time accomplished with boot polish) in Thank You, Jeeves.

O woman, in our hours of ease (p. 115)

O woman! in our hours of ease

Uncertain, coy, and hard to please,

And variable as the shade

By the light quivering aspen made;

When pain and anguish wring the brow,

A ministering angel thou!

: Marmion vi:30

feet of clay (p. 115) *

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

Bert Williams (p. 115)

Egbert Austin Williams (1875–1922). The celebrated Antiguan-born comedian died in March 1922, shortly before The Girl on the Boat appeared in book form, but Billie was presumably not aware of this. Charitably, one could assume that Sam is offended here because Billie assumed that he was imitating a black person (Williams), as opposed to imitating a white person (Tinney) imitating a black person, though this is probably reading far too much into the text.

(Note also the reference to Williams’s song “Everybody wants a key to my cellar” on p.70 above.)

small black golliwog (p. 116)

A doll representing a minstrel-show character, nowadays regarded by many as offensive to black people. The name was first used by Florence and Bertha Upton in the children’s book The Adventures of Two Dutch Dolls (1895). Enid Blyton and the jam makers James Robertson and Sons used golliwogs extensively.

Cf. the Mickey Mouse in The Luck of the Bodkins.

http://www.ferris.edu/news/jimcrow/golliwog/

captious critic (p. 119) *

See Sam the Sudden.

I fee-er naw faw in shee-ining arr-mor... (p. 119)

"I fear no foe in shining armour" is a drawing-room ballad with words by Edward Oxenford (1847–1929) and music by Ciro Pinsuti (1829–1888).

linnet (p. 119) *

See Summer Moonshine.

fine-mesh underwear (p. 120) *

See Bill the Conqueror.

Sigsbee’s Superfine Featherweight (p. 120)

A golfer called Sigsbee appears in the early story “Archibald’s Benefit” (1910).

Cf. also Slingsby’s Superb Soups (“The Spot of Art”) and a number of other minor Slingsbys in the canon.

a rag and a bone and a hank of hair (p. 122)

A fool there was and he made his prayer

(Even as you and I!)

To a rag and a bone and a hunk of hair

We called her the woman who did not care)

But the fool he called her his lady fair

(Even as you and I!)

Oh, the years we waste and the tears we waste

And the work of our head and hand

Belong to a woman who did not know

(And now we know that she never could know)

And did not understand!

The Vampire ll.1–11

commination service (p. 122) *

See Summer Lightning.

Borneo wire-snake (p. 123)

There doesn’t seem to be such a thing as a wire snake – perhaps Eustace is getting them confused with whip snakes or pipe snakes, both of which are found in Asia, but are said to be harmless to humans.

Worcester Sauce (p. 124) *

See above, p. 66.

The description, later on the same page, of the efficacy of Jane Hubbard’s mixture reminds us that Worcester Sauce is one of the ingredients of Jeeves’s pick-me-up, as described in “Jeeves Takes Charge” (“dark meat-sauce” in 1916/1923 magazine versions; revised in Carry On, Jeeves, 1925).

staggers (p. 124) *

See Very Good, Jeeves.

Chapter 8 (pp. 126 – 143)

Sir Mallaby Offers a Suggestion

This chapter is very different in the US edition – see the note to Chapter 9 below.

Southampton (p. 126)

Most transatlantic liners between the wars docked at Southampton (White Star) or Liverpool (Cunard).

Bingley-on-the-Sea (p. 126)

Bingley is one of Wodehouse’s favourite names, for both people and places. Bingley-on-[the-]Sea (or the similar Bramley-on-Sea) appears in many stories, most memorably in “Portrait of a Disciplinarian”. It is where the Drones have their golf tournament (“Jeeves and the Kid Clementina”), and it is the setting for the first part of Doctor Sally.

Sam seems to be the only visitor to take against it in this way — Bertie describes it as a place “where every prospect pleases” — his only objection to it is the presence of a school run by Aunt Agatha’s friend, Miss Mapleton.

There are also villages called Upper and Lower Bingley in “The Great Sermon Handicap”. Horace Davenport’s car in Uncle Fred in the Springtime is “a rakish Bingley” (Ch.15).

There is Bingley Crocker (Piccadilly Jim), Little Johnny Bingley (“The Nodder”), Elsa Bingley (secretary in Ice in the Bedroom), Gladys Bingley (Lancelot Mulliner’s fiancée), Lancelot Bingley (engaged to Gladys Wetherby[!] in “A Good Cigar is a Smoke”), Marcella Bingley (golfer), and Bertie’s ex-valet Rupert Bingley (né Brinkley). In Cocktail Time, Bingley vs. Bingley, Botts & Frobisher is the name of a divorce case.

In real life, there is a tiny Bingley in Denbighshire and a rather larger one in Airedale, West Yorkshire, but neither of them is anywhere near the sea. Murphy guesses that the most likely prototype is the south coast resort Bexhill-on-Sea, where Wodehouse’s parents lived in retirement.

Swiss waiters (p. 126) *

To those of us who have traveled in Switzerland in modern times and have been impressed by the service in Swiss hotels, Wodehouse’s disparaging references to Swiss waiters are difficult to understand, unless Switzerland made a point of exporting their less-competent staff to work in other countries. To be sure, the Swiss waiters at the Hotel Superba in Bingley-on-Sea in chapter 2 of Doctor Sally (1931) are merely mentioned as prowling among potted palms.

Owners of large private houses find it’s too much of a sweat to keep them up, so they hire a couple of Swiss waiters with colds in their heads and advertise in the papers that here is the ideal home for the City man. [...] No Swiss waiters here, but a butler…

“Ukridge and the Home from Home” (1931; in Lord Emsworth and Others, 1937)

“He did yodel a good deal,” admitted Evangeline. “He yodelled to the waiters.”

“Why to the waiters?”

“They were Swiss, you see.”

“Farewell to Legs” (1935; in Lord Emsworth and Others, 1937)

Hotel Magnificent (p. 126)

Perhaps this choice of hotel was Sam’s error – Bertie Wooster seemed to be very happy with the food at the Splendide in Bingley-on-Sea (see “Jeeves and the Kid Clementina”).

shingle (p. 127) *

A beach paved with small roundish pebbles rather than sand.

ozone-swept (p. 127)

It used to be believed that the air at seaside resorts was particularly healthy because it was rich in ozone. In fact, of course, ozone is a harmful pollutant, found in significant quantities only in big cities and in photocopier rooms. The “ozone” smell in the seaside air actually turns out to come from iodine in decaying seaweed.

Gehenna (p. 127) °

New Testament name for hell, deriving from the Vale of Hinnom, a valley south of Jerusalem. Occurs eight times in the NT (Matt. v. 22, 29, x. 28, xiii. 15, xviii. 9, xxiii. 15, 33; James iii. 6); the word Hades is slightly more popular, appearing nine times. (source: Brewer)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

Archilochum ... proprio rabies armavit iambo (p. 127) °

See Horace, Epistles II,iii (“Ars Poetica”), line 79. Among Greek poets whose work survives to any significant extent, Archilochus of Paros (fl. ca. 650 BCE) is the earliest to have written lyric poetry about his own experiences and emotions. The Greeks seem to have regarded him as one of their greatest poets, and Horace was a big fan. He probably didn’t actually invent the iambic trimeter, as Horace suggests, but he was certainly one of the first people to use it effectively.

The lady who rejected him was called Neobule, and comes in for some pretty strong criticism in his verses. As well as making him write satirical verse, his rejection by Neobule seems to have been the reason for his going off to become a soldier of fortune.

http://community.middlebury.edu/~harris/Archilochus.pdf

[Omitted in UK and US magazines and US book edition. These also omit the John Simmons case in the next paragraph of the UK book.]

to go off to the Rockies to shoot grizzlies (p. 128) *

See A Damsel in Distress.

[In US magazine, “grizzly bears”; in US book, “grizzly-bears.” Omitted in UK magazine.]

trains ... two hours (p. 128) °

Two hours is about the time it would take to travel from the Sussex coast to Charing Cross and walk to Fleet Street.

The UK magazine serial and UK book have a major cut here. The US magazine and book have a scene between Eustace Hignett and Sam in the hotel lobby in which Eustace tells Sam about his private arrangement with Mr. Bennett and Mr. Mortimer to lease Windles to them for the summer, and some of the complications that arise there with the rain, the bulldog Smith, the orchestrion, and Mr. Bennett’s plan to take legal advice from Sam’s father. This constitutes the remainder of Chapter 8 of the US book; a slightly shortened version is in episode 2 of the US magazine serial. Most of these complications are set out in Chapter 10 of the UK book, and are annotated below at that point.

Marlowe, Thorpe, Prescott, Winslow and Appleby (p. 128) °

In Leave It to Psmith there is a coal merchant in Dover Street called Thorpe & Briscoe. Thorpe & Widgery (see below for the latter) is the grocer’s shop in “Tried in the Furnace.”

Prescott is the name of a number of minor characters, the most memorable perhaps being Mabel, who collects for the Temple of the New Dawn in Laughing Gas.

The name Winslow appears elsewhere in the canon only in a reference to Claudia Winslow, an actress whose part Claire Fenwick is supposed to take over in Uneasy Money, ch. 1 (1916). It is the name of several towns in the US, while Winslow Homer (1836–1910) was a celebrated American artist.

Appleby is a name that pops up throughout the canon, from a master at Wrykyn in 1904 to a bank-burgling butler in 1968. It is the name of a town in Westmoreland, of course.

Ridgeway’s Inn (p. 128) °

Fictitious: presumably represents one of the ten Inns of Chancery: Barnard’s Inn, Clement’s Inn, Clifford’s Inn, Furnival’s Inn, Lyon’s Inn, New Inn, Staple Inn, Strand Inn, and Thavie’s Inn. These originally functioned as a sort of preparatory school for the Inns of Court, where barristers are trained, but by the nineteenth century had lost their educational function and simply provided “chambers”, i.e. office space, for law firms.

The Ridgeway is the ancient track that runs along the top of the North Downs in Berkshire and Wiltshire.

not far from Fleet Street (p. 128)

Very little connected with the legal profession is more than a few hundred yards from Fleet Street. The Temple (one of the Inns of Court) is on the southern side of Fleet Street, so perhaps Sir Mallaby’s firm is in one of the Inns associated with the Temple.

The brass plate… (p. 128) *

The UK book continues here immediately following “Fleet Street” in the preceding note. The UK and US magazines and US book continue the Fleet Street sentence with a longish paragraph about the grubbiness of the entry, stairs, and passage leading to the dark and grimy door of the law firm offices, which is “the gauge of a lawyer’s respectability.”

demurrer (p. 129)

A demurrer is an objection that the plaintiff is not legally entitled to relief, even if the facts are as claimed.

replevin (p. 129)

Replevin is something like bail, but for property, not people: When, in the course of a dispute, goods have been seized, the defendant can attempt to get them back until the case is decided, by lodging equivalent security with the court.

John Peters (p. 129) *

In both magazine versions, his given name is abbreviated “Jno.” here.

The People v. Schultz and Bowen (p. 131)

Criminal cases in the US are conducted on behalf of the People; in Britain it is the Crown that prosecutes (“R. v. Schultz and Bowen”).

There doesn’t seem to be any obvious Wodehouse connection in the names.

Rupert Street Rifle Range (p. 131)

Rupert Street is in Soho, just east of Piccadilly Circus, maybe 15 minutes’ walk from Fleet Street. Nowadays it’s known mostly for gay bars, but there’s no reason why there shouldn’t have been a shooting range there in the 1920s.

a film called ‘Two-Gun-Thomas’ (p. 131) *

IMDB.com lists a 1918 feature called Two-Gun Betty and several short films from 1911 to 1919 called The Two-Gun Man, Two-Gun Hicks, The Two-Gun Bad Man, The Two-Gun Parson, Two-Gun Girl, Two-Gun Gussie, and Two Gun Trixie. Later Disney short cartoons kept up the tradition: Two-Gun Mickey (1934) and Two Gun Goofy (1952).

speaking-tube (p. 132) *

See Leave It to Psmith.

blew down it (p. 132) *

Some speaking tubes were fitted with a whistle at each end to serve as a signal that a communication was about to start.

Miss Milliken (p. 132)

Letter-writing was a lot easier in the days before PCs and “standard” clauses (provided you had an intelligent and experienced secretary)...

Sir Mallaby’s stenographer seems to be the only Milliken in the canon, although there are a couple of Mulligans.

(The physicist who measured the electron charge in 1909 was called Millikan, not Milliken.)

Brigney, Goole and Butterworth (p. 132)

Brigney is a mystery – it seems to be very rare as a name, although rather common on the internet as a spelling mistake.

Goole is a town in East Yorkshire, developed as an inland port by the Aire and Calder Canal Company from 1826 onwards.

Butterworth is a fairly common English name (e.g. the name of a well-known publisher of legal textbooks).

None of these names features elsewhere in the canon, but there are quite a few Brinkleys, Gooches and Butterwicks.

http://www.google.com/jobs/britney.html

Mr. Wibblesley Eggshaw (p. 132)

This name seems to stand alone! There are a few placenames of the Wibbsleigh/Wobbley type in the canon.

Hyacinth (p. 133)

The original Hyacinth was a Greek youth, loved by Apollo, and killed in a sports accident. St. Hyacinth (1185–1257), the “Apostle of the North,” was a Polish Dominican who did extensive missionary work in the countries around the Baltic.

The short story “Hyacinth” (1906) by Saki (H. H. Munro) features an evil small boy of that name.

Wodehouse, with good personal reasons, often makes little jokes about “dirty work at the font.” To be called Hyacinth would have been bad enough for a young man, even without the fashion for “flower names” (Rose, Daisy, Marigold, etc.) for girls, that led to the name Hyacinth swapping genders in the course of the 20th century.

Dante (p. 133)

Dante Alighieri (1265–1321), Florentine poet. In his Inferno, he describes a visit to Hell.

Life is real! (p. 134)

Tell me not, in mournful numbers,

Life is but an empty dream!

For the soul is dead that slumbers,

And things are not what they seem.

Life is real—life is earnest—

And the grave is not its goal:

Dust thou art, to dust returnest,

Was not spoken of the soul.

Not enjoyment, and not sorrow,

Is our destin’d end or way;

But to act, that each to-morrow

Find us farther than today.

Art is long, and time is fleeting,

And our hearts, though stout and brave,

Still, like muffled drums, are beating

Funeral marches to the grave.

In the world’s broad field of battle,

In the bivouac of Life,

Be not like dumb, driven cattle!

Be a hero in the strife!

Trust no Future, howe’er pleasant!

Let the dead Past bury its dead!

Act—act in the glorious Present!

Heart within, and God o’erhead!

Lives of great men all remind us

We can make our lives sublime,

And, departing, leave behind us

Footsteps on the sands of time.

Footsteps, that, perhaps another,

Sailing o’er life’s solemn main,

A forlorn and shipwrecked brother,

Seeing, shall take heart again.

Let us then be up and doing,

with a heart for any fate;

Still achieving, still pursuing,

Learn to labor and to wait.

(1807–1882): A Psalm of Life

[Knickerbocker Magazine, September 1838, vol. 12, p. 189; updated 2015-12-08 NM; thanks to Dirk Laurie for spotting missing stanza]

Margate is too bracing (p. 135) °

Margate is on the north coast of Kent, and as such is probably a little windier than Sussex resorts like “Bingley”/Bexhill.

The phrase ‘...is so bracing’ was originally used by the Great Northern Railway on its posters to advertise trains to the Lincolnshire resort of Skegness. The town later adopted the phrase ‘Skegness is so bracing’ (and the jolly fisherman depicted on the railway poster) for its own publicity purposes.

in a cleft stick (p. 135) *

The girl is suing him... (p. 136)

Under English law, an engagement to marry was regarded as a binding contract and the party who repudiated the engagement was liable to be sued for ‘breach of promise.’ As a consequence of the Law Reform (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1970, actions for breach of promise were abolished as from 1 January 1971. An action for breach of contract was a civil law matter.

In an action for breach of promise, the plaintiff (man or woman) could sue for restitution of any pecuniary loss arising from outlay in anticipation of marriage. In some circumstances, a woman could also hope to be awarded substantial damages (‘heart-balm’).

torts and misdemeanours (p. 137)

A tort is a civil, as opposed to criminal, wrong.

Misdemeanour no longer has a technical meaning in English law, but before 1967 referred to criminal offences of types considered less serious than felonies.

Vic. I. cap. 3’s (p. 137)

Statutes in Britain were formerly cited by the year of the sovereign’s reign in which they were given the Royal Assent (like the “Emperor Years” used for official documents in Japan). Nowadays calendar years are used for most purposes.

However, Sam doesn’t have the format quite right: conventionally, statutes from the first year of Queen Victoria’s reign (1837) should be cited as “1 Vict., c. 3” (etc.).

The statute in question is: An Act to carry into further Execution the Provisions of an Act for completing the full Payment of Compensation to Owners of Slaves upon the Abolition of Slavery.

https://www.pdavis.nl/Legis_02.htm

pianola (p. 141) °

In later popular usage, “pianola” was often used as a generic name for player pianos, but the original device marketed under that name was an external attachment which could be wheeled up to the keyboard of an ordinary piano to play it automatically from a paper roll in a manner more familiar today from integrated player pianos. Invented in 1896 by Edwin Votey of Detroit, USA, it was a popular form of home entertainment until the 1930s, when the significantly cheaper gramophone began to replace it. The device was powered by two foot pedals, which generated suction to drive a paper roll (a ‘piano roll’) across a pneumatic reading device. Perforations in the piano roll represented the music to be played, the individual perforations triggering a pneumatic motor, which caused the appropriate piano keys to be struck by felt-covered wooden ‘fingers’ – one for each of the 88 keys of the piano.

snowy white tie ... dinner jacket (p. 141) °

In most houses at this time, formal evening dress (with a tail-coat and a white tie) would only have been worn on particularly grand or formal occasions. Here, Sir Mallaby is having guests, so has put on white tie and a tailcoat. On less formal occasions (but these included family dinners), gentlemen would wear the less formal dinner-jacket (US: “tuxedo”), which came into fashion in the 1890s, with a black tie. In this case, Sam’s father doesn’t consider that his party is so grand that the black-tie outfit that Sam is already wearing will be out of place.

The UK serialization in Pan makes this more explicit; following “in some consternation” the paragraph continues:

Sir Mallaby’s neat little barrel of a stomach was sheathed in a waistcoat of white and gleaming as his tie. The tails of his well-cut coat flapped to his knees. Sam himself, with his dinner-jacket and black tie, felt in comparison almost like a tramp cyclist.

I can hear them on the stairs (p. 143)

In larger town-houses, the main reception rooms would typically be on the first floor (US: second floor).

Chapter 9 (pp. 144 – 158)

Rough Work at a Dinner Table

In the US edition, there is a meeting between Eustace and Sam at Bingley at the end of Chapter 8, while Chapter 9 contains Sam’s return to his father’s office (the second half of Chapter 8, pt.1, in the UK edition). The dinner party scene is not in the US edition at all.

cold fury (p. 144) *

See above.

toy of Fate (p. 144) *

Of Mike he took no further notice, leaving that toy of Fate standing stranded in the middle of the room.

Psmith in the City (serialized as The New Fold), ch. 4 (1908/10)

He was thinking of Beefy Bastable, that luckless toy of Fate who … would shortly be parting with several hundred pounds for an imitation walnut cabinet worth perhaps fifty shillings.

Cocktail Time, ch. 22 (1958)

five-reel film scenario (p. 144) *

The plot outline of an ordinary feature film of that era, of average length rather than being anything spectacular. See p. 56, above.

slow fade-out on the embrace (p. 145) *

See Bill the Conqueror.

“When I took my temperature at twenty minutes to six…” (p. 147) *

The UK serial in Pan has a longer passage instead of this sentence and the next one. Following “cancel this dinner engagement” Mr. Bennett continues:

I had shooting pains in the small of my back, my tongue was furry, and there were distinct indications of fever. Fortunately, I pulled round a little subsequently, but I am still a sick man. When I prod myself sharply in the side, there is pain. I don’t know what to do about it.”

“Abstain from prodding yourself,” said Mr. Mortimer, Senior, judicially. He gave out his lightest utterances as if he were administering professional advice to an anxious client. Just as few parrots have ever looked so parrot-like as Bream, few lawyers have ever looked so like lawyers as Mr. Mortimer. In repose he had always an air of waiting to be consulted on some point of legal interest.

“Capital suggestion!” said Sir Mallaby cheerily. “You are among friends, Bennett. If you don’t prod yourself, nobody here will prod you.”

The UK serial continues with “Sir Mallaby’s dinner table…”

Ouseley v. Ouseley, Figg, Mountjoy, Moseby-Smith and others (p. 147) °

The style of citation – plaintiff and respondent with the same surname – suggests that this is a complicated divorce case. The other parties named would be co-respondents, i.e. people alleged to have been involved in adultery with the respondent. Until the reform of the divorce laws in the 1960s, to prove adultery was in practice the only straightforward way to obtain a divorce.

Ouseley is an Irish name: Sir William Ouseley (1762–1849) was a great oriental scholar, who did a lot of field work in Persia, where his brother, Sir Gore Ouseley, was British ambassador. Sir Gore’s son, Sir Frederick Arthur Gore Ouseley (1825–1889) was a noted music educator and composer of English church music.

Gideon Ousely (no relation: 1762–1842) was a celebrated evangelical preacher in Ireland.

James Figg (1695–1734) was a celebrated boxer, usually credited as Britain’s first heavyweight champion.

William Blount, 8th and last Baron Mountjoy (1563–1606) was Queen Elizabeth’s Lord Lieutenant in Ireland. He was later created Earl of Devonshire.

The name Moseby seems to be more common in Denmark than in the English-speaking world, but it does appear occasionally.

[The UK serial omits mentioning the discussions among the older generation, ending this paragraph at “impossible.”]

crumbling bread (p. 148) *

A frequent indication of nervousness at the dinner table:

“It suddenly came to me,” said the inspired one, modestly crumbling bread.

“The Matrimonial Sweepstakes” (1910)

Leaning forward, he addressed the bearded man, who was crumbling bread, with an absent look in his eyes.

“Brother Fans” (1914)

He had filled in the time mostly by crumbling bread, staring wildly and jumping like a galvanized frog when spoken to.

Ring for Jeeves, ch. 17 (1953)

It was at this point that Freddie, who had been crumbling bread, started as if electrified.

French Leave, ch. 8.3 (1956)

…admirable though the dinner was that Willoughby’s cook had served up, it is not too much to say that it turned to ashes in Homer’s mouth. He sat crumbling bread and fearing the shape of things to come.

The Girl in Blue, ch. 5.3 (1970)

tarn (p. 148) *

A small mountain lake. This is apparently Wodehouse’s only usage of this specific geographical term, derived from North British dialect.

corn-on-the-cob (p. 149) *

See Piccadilly Jim.

hock (p. 149) *

See Something Fresh.

the sex (p. 150) *

“The sex” as shorthand for “the female sex” dates from 1589 but is no longer in common use.

work … was becoming raw (p. 150) *

See Money for Nothing.

heir of the Mortimers (p. 150) *

See Bill the Conqueror.

absently balancing his wine glass on a fork (p. 150) *

“The way she looked at me when I was doing that balancing trick with the nut crackers and the wineglass.”

Summer Moonshine, ch. 17 (1937)

It was [Tipton Plimsoll] who, in between the soup and fish courses, entertained the company with a diverting balancing trick with a fork and a wineglass.

Full Moon, ch. 4.2 (1947)

“Chronic dyspepsia,” said Mr. Bennett authoritatively (p. 154) *

Like many hypochondriacs, Mr. Bennett considers himself well-educated in medical matters, and thinks that he can diagnose persistent indigestion in others by merely looking at them.

orchestrion (p. 155) °

Orchestrion is a generic term for automatic musical devices that imitate an orchestra by playing a variety of instruments controlled by a punched paper roll. They were usually based around a piano and/or organ mechanism. They could be fitted with an automatic roll-changer, allowing them to be used as coin-operated “jukeboxes” but playing their own contained instruments rather than recordings. Most seem to have been built in Germany.

A 1914 Weber orchestrion, demonstrated on YouTube

unhitched your brain (p. 157) *

See Bill the Conqueror.

See also below, p. 294.

Trappist monk (p. 157) *

See Right Ho, Jeeves.

Chapter 10 (pp. 159 – 179)

Trouble at Windles

Chapter 10 is much shorter in the US edition – it goes straight from Mr. Bennett looking out at the rain to his interview with Billie, omitting most of the incidents in the UK version (some of which had been recounted by Eustace to Sam in chapter 8 of the US book).

Flood ... Noah (p. 160)

As anyone who has lived in the North-West of England will confirm, it hardly rains at all in the South-East.

See also Biblia Wodehousiana.

bridge (p. 161)